Legal Lexicon

This month’s column is devoted to a glossary of frequently used legal terms:

Abatement: Eliminate, reduce, e.g. abate a nuisance; abatement of rent.

Adjourn: Postpone.

Abscond: To leave unlawfully with the intent of not returning.

ACD: Adjourned in Contemplation of Dismissal. Possible disposition of violations or misdemeanors.

Affidavit: A statement signed and sworn to in the presence of a Notary Public.

Affidavit of Service: A sworn statement that documents were served (delivered).

Affirm: Appellate court decision agreeing with lower court. Also, an alternative to swearing to tell the truth, e.g. Do you swear or affirm?

Allocution: Questions and answers at end of court proceedings to establish certain facts, e.g. litigant understands when he/she is giving up a right.

Appeal: Seeking to have a higher court modify or overturn a court decision.

Arbitration: A forum for dispute resolution. A private justice system which is binding on the parties. Popular in credit card agreements, and employment contracts.

ATI: Alternative to Incarceration. Sentence in lieu of imprisonment, e.g. drug program.

Bail: Sum of money (or property) posted to insure a criminal defendant’s return to court.

Calendar: A court’s list of cases. Also, docket.

Civil: Law surrounding private issues; not criminal.

Contempt: Violation of a court order.

Contingent Fee: A fee charged for a lawyer’s service only if the lawsuit is successful.

Condominium, Condo: A building or complex containing a number of individually owned units.

Cooperative, Co-Op: Property run by its members who own shares in a corporation, but not the real estate itself.

Contract: An agreement between two or more competent parties creating promises and exchanges.

Damages: Money as compensation for injury or loss.

Deed: Written instrument of ownership, usually of real estate.

Default: An adversary’s failure to appear or participate in proceedings.

Deposition: Out of court sworn testimony. Also, known as EBT’s.

EBT’s: Examination before trial. See Deposition.

Equitable Distribution: Division of marital property.

Ex parte: One party, e.g. plaintiff confers with judge in absence of defendant.

Felony: Serious crime.

Franchise: The right to vote. Disenfranchise: Take away the right to vote.

Holdover: Remaining in possession of real estate after landlord has deemed the lease terminated by some act or conduct of the tenant.

Indictment: Grand Jury’s finding that a crime has been committed and that the accused is probable perpetrator.

Inquest: Mini trial conducted by plaintiff after defendant has defaulted.

Jail: Sentence of short term local incarceration (under one year) or in a local holding facility awaiting trial.

Judgment: Legal proceedings end with entry of judgment.

Jurisdiction: A defined place. Also, power over.

Mediation: Non-binding effort by a neutral person to resolve dispute.

Negligence: Breach of a duty of care which results in damage. Doing something or failing to do something which a reasonable person would do, and which causes injury.

Misdemeanor: Low level crime.

Notary Public: A person authorized to administer oath and witness signing of affidavit and legal documents. In the United States, a Notary cannot give legal advice.

Order to Show Cause: An order directing a party to appear in court and show why the court should not order certain action.

Parole: Supervised release from prison after serving most of a felony sentence. Also, released by judge without bail.

Plea: A formal statement by or on behalf of a defendant, stating “guilty” or “not guilty.”

Prison: State facility for incarcerating convicted felons.

Pro Se: Self-representation.

Probation: Supervision as an alternative to incarceration.

Remand: Incarcerate without bail. Also, returning a case to original court.

Rent Control: Regulations regarding rent and building services enacted in 1947 due to housing emergency.

Rent Stabilization: Regulations enacted in late 1960's in response to housing emergency.

Retainer: Written agreement to hire a lawyer. Also, the fee paid to hire a lawyer.

Reverse: Court or jury decision changed by appeals court.

ROR: Release on Own Recognizance. A criminal defendant released without bail or paroled.

Service: Delivery of legal documents in prescribed manner.

Settle: Agreeing on terms to end a case without trial.

Statute: Law enacted by legislature.

Statute of Limitations: The time at which the right to prosecute a civil or criminal action expires.

Stay: Order stopping action for a finite time.

Stipulation: An agreement between opposing parties.

Subpoena: An order to appear before the court and/or provide documents.

Summons: Notice that a lawsuit has been convened and an answer must be served. Also, notice to appear for jury duty.

TRO: Temporary Restraining Order. An order stopping (or demanding) an imminent action, e.g. an eviction.

Tort: A civil wrong in which damages are claimed.

Traverse: A hearing to contest or establish proper service of legal documents.

Violation: Unlawful act which can result in arrest and incarceration but is not considered a crime, e.g. disorderly conduct.

Waiver: Giving up a right, a legal position or argument.

Warrant: A written order directing or authorizing an act, e.g. arrest, search..

Youthful Offender, Y& O: Status of some criminal defendants under 19.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court JusticeÂ

The Attorney General

One hundred and ninety years after Martin Van Buren used the position of attorney general to try to topple the governor, candidates Jeanine Pirro and Andrew Cuomo are trying to topple one another. Over and over again during their recent debate -- 16 times by one count -- Republican Pirro hammered her Democratic rival for a lack of experience, saying that as a junior prosecutor for only 14 months 21 years ago he did not understand the criminal justice system or know how to run a legal operation. And for good measure, she accused him of corruption.

For his part, Cuomo charged that Pirro is under investigation not only for seeking to wiretap her husband Albert, whom she suspected was having an affair, but also for failing to pursue corrupt officials in Westchester County. (Two days later, current Attorney General Eliot Spitzer said there is no such corruption probe.)

Such heated contests are nothing new for attorneys general.

The job was a source of friction between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton. Burr defeated the Hamilton faction to win appointment as attorney general in 1789. The animosity between the two men continued for the next 15 years, until 1804, when Burr killed Hamilton in a duel.

Spitzer's predecessor, Republican Dennis Vacco, got the job after making it clear to any New Yorker who cared and many who did not that his opponent Karen Burstein was a lesbian, something she never sought to hide. Four years later, Vacco lost to Spitzer by a narrow margin but refused to concede until six weeks after Election Day, blaming his defeat on voter fraud.

All this conflict surrounds an office that in the past has been described "a bureaucratic and legal backwater," and "one of the state's least glamorous jobs."

FIGHTING FOR A 'BACKWATER'?

Even the two current candidates, who are spending millions this year to win the office, have not been very excited about the job, at least initially. Cuomo only sought the job after being forced to drop out of the race for governor in 2002. Pirro first tried to run for U.S. Senate this year, and in a taped conversation with Bernard Kerik said that being attorney general is a "been-there-done-that kind of thing."

|

The Other Statewide Offices Attorney general is one of four state offices whose occupants are elected by all New York State voters. All these posts are up for election this year: Governor: Twelve years ago Republican George Pataki scored an upset when he unseated incumbent Mario Cuomo to become the state's chief executive. With Pataki stepping down this year, the race to replace him has seemed a bit muted for a campaign for such a powerful post. Attorney General Eliot Spitzer easily defeated Democratic rival Tom Suozzi in the primary and now has a commanding lead in polls and in fundraising against former State Assemblymember John Faso. Lieutenant Governor: The state's number two office has little power. It is so obscure that only political junkies or the current occupant's friends or famiy can name her (Mary O'Donohue). The office got a little bit of buzz in Pataki's first term when then Lieutenant Governor Betsy McCaughey Ross raised eyebrows as she stood behind Pataki through 58 minutes of a speech he was making to the legislature. Pataki dumped Ross. In response she switched to the Democratic Party, announced she would run against Pataki and floundered badly. Just as the vice president runs with the president, lieutenant governor candidates run with governor. This year the Democrats have an unusually prominent candidate for the number two job: State Senate Minority Leader David Paterson of Harlem. Paterson is so prominent many wonder why he would want the job. If he wins, New York would "have affirmed an important principle: An African-American has the same right as anyone else to hold an inherently forgettable elective office," Clyde Haberman wrote in the Times. His Republican opponent is Rockland County executive Scott Vanderhoef. Comptroller: Former City Comptroller Alan Hevesi now holds the post of the state top fiscal officer. His re-election campaign garnered little notice until the Republican candidate, former Saratoga County Treasurer Chris Callaghan, found out that Hevesi had used a state employee to chauffeur his wife. Hevesi apologized and reimbursed the state almost$83,00, but the incident has prompted speculation about the integrity of someone entrusted with insuring the integrity of state finances. Despite that, Callaghan/s campaign continues to struggle, with little money or visibility. The Assembly speaker and the State Senate majority leader, though wielding enormous power throughout the state, are like other members of the legislature elected only by the residents of their districts. The members of the legislature then chose them for their leadership posts. |

But however some may disparage the job it certainly has a pedigree -- going back to the days of New Amsterdam when the schout fiscal was appointed by the West India Company to protect the company's interests in the colony and enforce laws and ordinances. And the job seems an essential part of government: Many nations and all 50 states have an attorney general.

Oliver Koppell, who held the office in New York State in 1994 and now serves on the New York City Council, likens talking about the office of attorney general to the old story about blind people describing an elephant. That, he says, is because "it has so many disparate functions that it can be described in so many ways."

Certainly, there are considerable administrative responsibilities. The office has over 500 attorneys and over 1,800 employees, including forensic accountants, legal assistants, scientists, investigators and support staff, and an annual budget of about $224,000,000.

In general, "the state attorney general is the chief litigator defending the state, the counselor rendering legal advice to state officials and the public advocate enforcing law designed to protect consumers, small businesses and the environment," Charles Burson, then attorney general of Tennessee and president of the National Association of Attorneys General once wrote.

The New York State constitution says little about the role of the attorney general beyond how the attorney general is selected (by election the same year the governor and comptroller are chosen) and that he or she heads the department of law. The duties of the state attorney general are set out in state law. These include, though are not limited to:

-- Criminal prosecution: The attorney general does not handle standard criminal cases but does bring cases against people who have misused state money. It can also investigate and prosecute cases of Medicaid fraud and corruption and works with local and federal officials on organized crime.

-- Protect the public interest: The Office of Public Advocacy can conduct investigations and file lawsuits, in areas such as antitrust, civil rights, consumer fraud, environmental protection, real estate and, most recently, internet transactions.

-- Collect revenue: As the state lawyer, the attorney general goes after people who owe New York money, including patients at state hospitals who didn't pay their bills and students at the state university who failed to pay tuition or repay their loans.

-- Defending the state: The attorney general is the legal counsel for the state and for state employees facing lawsuits related to their duties. These cases can range from sweeping suits, such as the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit challenging the state's financing of New York City public schools, to malpractice cases brought against state hospitals.

This can be tricky when, as is now the case, the governor belongs to one party and the attorney general to another. In the school funding case, candidate Spitzer has said that, if elected, the city schools would get billions more, while Attorney General Spitzer has defended in court the governor's refusal to increase funding. "If you do anything less than that, you're not doing your duty," Spitzer press secretary Dennis Dopp has said.

But despite these various responsibilities, Koppell says, "the most frequent thing is to ascribe to [the office] functions that it does not have." For example, while many attorney general candidates over the years have sought to portray themselves as law and order candidates, the office has little responsibility for prosecuting standard crime; that task belong to local district attorneys.

A BROADER ROLE

But most recent attorney general have gone beyond the strict confines of the office, using their power to take up a variety of causes and filling gaps in the federal government's enforcement of the law. "The attorney general's office is capable of enormous elasticity," one former occupant, Robert Abrams has said. "The occupier of the office exercising leadership and his own degree of activism has the flexibility to move in certain direction."

In the 1920s, Attorney General Albert Ottinger, described as "a forebear to Spitzer in many ways," shut down the Consolidated Stock Exchange and said his legacy had been to "hammer, hammer, hammer at every manner and means of fraud and dishonesty."

Louis Lefkowitz, who served from 1958 to 1977, began taking on consumer protection. His successor, Robert Abrams, continued with that, cracking down on fraudulent and misleading phone and mail solicitations, enforcing the state's lemon law for cars, pursuing mail companies for fixing prices and suing businesses over confusing advertisements.

In doing this, Abrams was stepping into a void left by the federal government, which during the Reagan administration had little inclination to go after companies that hoodwinked or cheated consumers. "From a national perspective, we had a wasteland of consumer and environmental protection n the 1980s. It was critical that the states stepped in," Ed Mierzwinski, consumer program director for the U.S. Public Interest Research Group has said.

Similar, Koppell said that during his own year as attorney general he took up anti-trust actions, blocking a merger bid by Federated Department stores. Anti-trust also held little interest for the Reagan Justice Department.

But most agree that, for better or worse, Spitzer took things up a notch when he assumed office in 1999. "Eliot Spitzer has really pushed the envelope," Koppell said, particularly on issues involving Wall Street. He took advantage of a largely somnambulant state securities law called the Martin Act to go after Merrill Lynch for issuing false and misleading recommendations on stocks. As Abrams had done with his consumer work, Spitzer was filling a gap left by the federal government. "A feckless Securities and Exchange Commission has responded haphazardly to five years of scandal, leaving a vacuum for Spitzer to fill," wrote Daniel Gross in Slate.

He also pursued insurance companies and worked with city green grocers to agree to better working conditions for their largely immigrant workforce.

And, with the federal government under President George W. Bush reluctant to do much about pollution or global warming, Spitzer, along with seven other attorneys general and New York City officials in 2004 filed suit against five of the largest producers of the gases that cause global warming. In a kind of legal understatement, they used common law against creating a nuisance to support their claim. "Global warming threatens our health, our economy, our natural resources and our children's future," Spitzer said at the time. "Under accepted and unambiguous law, a court can order them to reduce their emissions."

Some critics think that during his eight years in office Spitzer has sometimes overstepped the bounds, partly to boost his own political future. "On the one hand, everybody respects that the attorney general filled a vacuum and cleaned up a series of abuses left over from the boom period of the late 1990s," Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership for New York City, a business group, told the Washington Post, "but there's an exhaustion factor that comes into play. . . . Every day it's a new issue."

"The problem with Eliot Spitzer and frankly a lot of the federal prosecutors is, in their zeal to appease public sentiment about various business practices, they've gone extreme," New York defense attorney Edward J.M. Little has said. "Almost any questionable business practice can be labeled a fraud."

WHAT WOULD PIRRO AND CUOMO DO?

The increased activism of attorneys general - in New York and elsewhere - may well continue after Spitzer moves on. "It is a position that is likely to grow in importance as the nation's Supreme Court, increasingly pro-state's rights, is expected to send a greater number of decisions back to the states for judgment," commented the public affairs television program NOW, which has covered state attorneys general extensively.

Certainly both major party candidates to become New York's 64 attorney general have set out ambitious, though widely different, goals.

Stressing her experience as Westchester district attorney, Pirro said one of her top priorities would be going after sexually violent predators. "My mission is to make sure we have civil confinement...to keep them away from our women and children" she said.

But, while expressing concern over sexual violence, Cuomo disputed Pirro's vision of the attorney general's job. "It's not a DA's office. We have 62; we don't need a 63rd," he said."

On the other hand, Cuomo wants to use the office to address political corruption and dysfunction in Albany. "The attorney general should be the chief public integrity officer," he said.

Some critics fault Spitzer for not having done more in this area. But Koppell thinks the attorney general cannot function as a crusader against corruption because it conflicts with one of the office's key roles. "How can the lawyer for state officials investigate wrongdoing by those officials?" he said.

Cuomo would continue Spitzer's policy of, as the candidate phrases it, "sticking up for the little guy" against big banks, corporations and the like. And Pirro and Cuomo agree both say they would use the office to go after Medicaid fraud

So does that make all the campaigning, the attacks, and the swirls of accusations worth it?

The attorney general position does have another thing going for it: Many occupants, including the current one, have tried to use it as a steeping stone. Lefkowitz lost a bid for New York City mayor to Robert Wagner and Abrams failed in his effort to be elected the U.S. Senate. Others such as Martin Van Buren and Jacob Javits, succeeded. Spitzer clearly hopes he follows in their footsteps.

But even if a term or two as attorney general does not lead to loftier public office, there is another reason to take the post Koppell says: "It's a wonderful job...You can make a difference in little ways and big ways."

Â

The Forgotten Attack On NYC

German spies attacked New York on July 30th, 1916. By blowing up a munitions depot on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, Germany slowed the shipment of supplies to Britain and France from the ostensibly neutral United States. The explosion also caused enormous physical damage to the surrounding area, blowing out windows of buildings as far north as the public library on 42nd street.

German spies attacked New York on July 30th, 1916. By blowing up a munitions depot on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, Germany slowed the shipment of supplies to Britain and France from the ostensibly neutral United States. The explosion also caused enormous physical damage to the surrounding area, blowing out windows of buildings as far north as the public library on 42nd street.

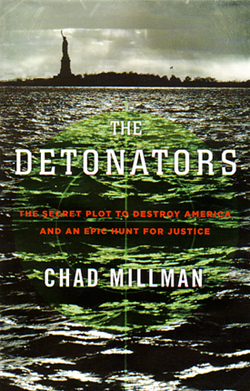

Despite being one of the largest attacks on New York in the city's history“ and a major terrorist attack on US soil planned and carried out by agents of a foreign government“ the event soon passed into obscurity. Chad Millman's book, The Detonators, tells the story of Black Tom Island. He recently joined Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club to discuss the attack on the city.

A FORGOTTEN CHAPTER OF HISTORY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Your book details a brazen terrorist attack carried out by a group of foreign nationals who are angry at American foreign policy. The details of the event bear a creepy resemblance to 9/11. Was it this resemblance, Mr. Millman, that inspired you to write the book?

CHAD MILLMAN: Absolutely, 100 percent. I've written some other books, but I'm a sports writer by trade. For my last book, I spent six months in Las Vegas tracking down people who bet on sports for a living, and I just didn't want to talk to anyone who was alive anymore. I wanted to deal with people who weren't around, and I could just dig into the research.

One of the things I've always liked to read is narrative non-fiction history. I was researching online on an "On This Day In History" web site. I started on January 1, 1900, and went through 1901, 1902, 1903, spending the better part of a day doing that until I got to July 30, 1916. There was a two-line description saying, "German terrorists blow up New York Harbor, much of downtown Manhattan destroyed." This was in March of 2002. I was living in Manhattan at the time, and I thought, "How have I not heard of this?"

I Googled and did some research, and there was nothing substantial written about it. I was stunned.

MARTHA SOFFER: Was this intentionally suppressed to save our macho American image that we've never been attacked?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, I don't think it was intentionally suppressed. At the time it was brushed aside. President Woodrow Wilson was campaigning on the banner that he had kept us out of war; he believed in peace morally and politically at all costs. There were several events leading up to this where there was a great amount of evidence that there were German spies operating in the United States, and that there were acts of sabotage in other munitions depots in the United States. Wilson's policy had been, "I don't want to know about this, I don't want to talk about this, I don't want this to be something we give credence to, because I don't want to go to Germany yet." Wilson's first response“ he was off the coast of Virginia on the Mayflower practicing his speech for the Democratic National Convention at the time“ was to say, "I'm not going to concern myself with the events at a private railroad." His Bureau of Investigation chief said in the New York Times that it was an accident. They clearly were trying to keep attention away from any act of espionage, because they wanted to keep the peace.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why do you think it's been completely forgotten about since then?

CHAD MILLMAN: I've been asked that question a lot, and I don't have a great answer. In terms of its place prior to World War I, it wasn't the thing that led us to war; that was the Zimmerman Telegram. If this is categorized as part of the World War I genre of history, then the final thing that catapulted us to war was that telegram, and this doesn't merit that level of attention. That's the only thing I can come up with; I haven't read anything better or heard of any better reasoning.

NEW YORK UNDER ATTACK

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In your research did you find out about any other attacks on New York City?

CHAD MILLMAN: There's always political anarchy, smaller attacks. Just a few years ago there was a bomb planted across from the post office on 50th street. In the early 1920s there was a lot of political anarchy and the Communist movement was underfoot.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: A book we talked about a few years ago described a plot by the confederacy to burn down several landmarks in New York City in the 1860s. But it was thwarted.

CHAD MILLMAN: It was such a battlefield back then. There was also that story about the German submarine off of Long Island in the 1940s, but nothing ever came of it.

It's awfully scary to think about all the things that has gone on and never happened. In the book I write about a group called the Black Hand in downtown Manhattan “basically Mafia“ they had been harassing and planting bombs in lower Manhattan. This led to an anarchist movement that was planting bombs. A lot of times they got caught because they blew themselves up. A lot of times you rely on the stupidity of criminals to uncover the deadliest plots.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Like when the Weathermen blew themselves up in the townhouse on East 11th Street.

WORLD WAR ONE IN NEW YORK CITY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the economy of New York City was based on the war before the United States joined the fighting, and how did that change once the US did go to war?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, I don't know New York specifically. Throughout the country the exports to Britain and France increased hundreds of millions, billions, maybe. Phenomenally huge.

STEVE ARONSON: If the United States were neutral at the time [immediately before the Black Tom attack] what basis did we have to intern these German ships, and not allow them to leave?

CHAD MILLMAN: Our argument was that letting them leave was tantamount to supporting an act of war. If they came here, refueled, restocked, and strengthened themselves, then we were aiding Germany in the act of war.

STEVE ARONSON: What about the British ships?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, British ships, too. The thing was there was a British blockade in the Atlantic. It was the German ships, when they got caught on the wrong side of the blockade, who couldn't get back to Europe.

STEVE ARONSON: I would consider that an act of war.

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, Germany did. That's why they were so angry; they felt the American policies were hypocritical. There were all these interned German sailors in Baltimore and New York, and up the East Coast. With Black Tom, the largest munitions depot, in view of Manhattan, the Germans would see these ships loaded with munitions steaming off to war. They were angry, because American companies were selling munitions, and Wilson wasn't stopping them. The Germans couldn't buy these munitions, so their best bet was to blow them up.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You write about the immediate physical damage in Jersey and Manhattan. Was there a larger economic impact?

CHAD MILLMAN: There was. It's funny, the mayor in 1914, when New York Harbor was becoming the busiest, wealthiest port in the country, said aloud "I fear for what would happen if someone tried to destroy this harbor." Immediately they declared you couldn't have munitions depots like this near large, populated areas. So yes, there was economic impact. I didn't see specific numbers; I just saw anecdotal evidence from people at the time saying how this was impacting the harbor. There were a lot of people looking for work at the time, so there were a lot of people out of work.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Did you find that there was anything similar to the feeling after 9/11 that people were worried that New York wouldn't seem safe anymore?

CHAD MILLMAN: No, I didn't get that at all. It was a different time. Before 9/11, it was such a placid, lush, flush environment in the US. It was so peaceful; there was no sense that this was coming. In 1916 there was a war going on in Europe, and there was a definite schism in the United States about whether we should go to war. This was after the Lusitania, and it was palpable that war could become inevitable. I don't think that people were as afraid as we are now.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Did you get the sense that the attack meant something different to people in New York than it did to people elsewhere?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, there wasn't this thing about rallying around New York as a victim like there was after 9/11. News traveled slower back then; there wasn't the instant reaction in places like Chicago and San Francisco that there was to 9/11.

GERMANS IN THE UNITED STATES AND NEW YORK

STEVE ARONSON: There must have been a group of people saying, "This was Germany." What impact did that have on American psyche at the time?

CHAD MILLMAN: Almost immediately there was a feeling that Germany had done this and that nothing would be done about it. There had been acts of sabotage leading up to Black Tom, and those had been written about in the papers often. It just became accepted that Germany was doing this, but that we weren't doing anything about it because we didn't want to go to war.

We also have to remember that while people died at Black Tom that wasn't the main goal of the saboteurs. They wanted to blow up the munitions depots so that the bullets didn't go to the front and kill Germans. They didn’t want to kill people like terrorists today. That's why there wasn't as palpable a fear.

MARTHA SOFFER: The German Americans were a very large, significant population.

CHAD MILLMAN: It was huge. Between 1880 and 1920 there was as many German Americans coming to the US as any other immigrant group. Before World War I, there was no immigrant group that was as admired or trusted as German Americans. There was a sociological study at the time that said that of all immigrant groups coming to the United States, it was German Americans who had the morals and principals that Americans most identified with.

Then World War I began, and all of a sudden there was this split. German Americans of first and second generation who had seemed so assimilated to the United States were suddenly staunchly in support of the motherland. And that's when a lot of the divisions happened. It became so bad that at one point they changed the name of sauerkraut to liberty cabbage. There were German communities all over the East Coast where the names of streets were changed. There was a street in Jersey City, Germania, whose name was changed to Liberty Avenue. They stopped teaching German at schools; German nurses weren't allowed to serve in the Red Cross because there was a fear they would grind up glass and put it into bandages. So there was a real fear of the German culture.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Just like French fries and freedom fries.

CHAD MILLMAN: There were so many times when my eyes would just bug out of my head, because I would be like "are you kidding me?" The similarities were stunning.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: New York City used to have an enormous German population and influence. Today this doesn't seem to be as significant as the Jewish, Italian, or Irish influences. Does that have something to do with the anti-German sentiment around this time?

CHAD MILLMAN: No, it didn't. The Germans settled here in two waves: the mid-1800s and the early 1900s. Unlike a lot of the Irish who were coming, the Germans came here with money. A lot of times they were leaving Germany for political reasons, and not because they were poor. So they came here with a lot of skills, built businesses, and by the early 1900s when the Irish and the Jews were immigrating here in larger numbers and settling on the Lower East Side and places like that, a lot of the Germans were moving to the Upper East Side, to Brooklyn, and to New Jersey“ to what was considered the suburbs.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Aside from the name changing and the things you mentioned, was there any actual persecution of German Americans living here at the time?

CHAD MILLMAN: There were stories of German priests being lynched when they were giving German last rites to people, and a lot of stories of violence against Germans when there were outward symbols of German heritage practiced by them.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were there any government-sponsored actions that targeted German Americans?

CHAD MILLMAN: There weren't any outward acts of violence that the government was supporting. A lot of that was after the war. The American Civil Liberties Union started after the war to combat the persecution of people who were thought to be communists. That was a much more fearful time about the government curtailing civil rights than pre-World War I.

JERRY SILVER: When Pearl Harbor hit and a decision was made to intern the Japanese, was there some discussion at that time about doing anything to the Germans?

CHAD MILLMAN: You know it's funny, there wasn't. I've been asked that a lot. I didn't research this to any great extent, but there wasn't as great a fear of Germany because they hadn't attacked us. There was a fear of the Japanese because of Pearl Harbor, and there were other reports that there were Japanese submarines sending signals to citizens in California.

MARTHA SOFFER: The German population was so large, you couldn't intern them; the Japanese population was small. Plus the Germans could pass.

THE LESSONS FROM BLACK TOM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Directly after 9/11, the FBI began to examine the Black Tom bombings, to reopen its files and look at what it had. Did it find anything instructive or useful in that comparison?

CHAD MILLMAN: They just reacquainted themselves to the case. They didn't find anything that was so useful to find out why this happened on September 11, or when another one could happen.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Have you tried to come up with lessons learned from that event yourself?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, the lessons learned were more applicable to World War II. The second half of the book is all about the investigation, and the efforts of three American lawyers to prove that Germany had done this. The lead lawyer was a man named John McCloy, who went on to have a distinguished career in politics. He was one of the architects of our Cold War strategy, and he was the first civilian high commissioner to Germany. His nickname was the chairman, because he was the chairman of the Chase Bank, and the Council on Foreign Relations, and the World Bank, and was an advisor to every president between FDR and Reagan.

McCloy became FDR's assistant secretary of war in the run up to World War II, mainly because of his work with Black Tom, and his work in investigating Germany. After Pearl Harbor, the discussion of the internment of the Japanese came up. FDR was well aware of the sabotage of Black Tom Island, and espionage, and enemies within the United States during World War I. They were both afraid of further attacks, and after they figured out a way where they could constitutionally do this, FDR was quoted as saying, "We don't want another Black Tom."