Hillary, Rudy, And George, But Not Mike ( Or So He Says)

After jumping onto the subway tracks to save a stranger, hero construction worker Wesley Autrey was lavished with gifts and acclaim, including a ceremony at City Hall at which Mayor Michael Bloomberg presented him with a Bronze Medallion – the city's highest honor for civic achievement – and some advice.

Aim for the White House, Bloomberg said; "we need another presidential candidate."

Bloomberg was joking, of course. It has been hard not to hear about the four New Yorkers who are already crowding the field in next year's presidential race (five if you count Al Sharpton, which few people seem ready to do). Senator Hillary Clinton, former mayor Rudolph Giuliani, former governor George Pataki, and Mayor Bloomberg himself are all coyly considering campaigns, though it's not certain how many of them will pull together serious efforts. The Democrats announced last week that they won't hold their 2008 convention in New York City, but you would have to forgive someone for thinking that, as New York magazine put it, "the road to the White House is an extension of Park Avenue."

It has been awhile since the days when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in the White House, eager to hear new ideas about how he could help his fellow New Yorkers. The last New Yorkers to head a major party ticket was Thomas Dewey in 1948. Since his near-miss, no New Yorker has even gotten close. Perhaps the closest was Senator Bobby Kennedy's 1968 campaign – a bid that ended in assassination.

Not coincidental to this dry spell, say many experts, is the persistent anti-urban bent of the federal government over the last several decades, which has drained New York of resources and made being from the Northeast a political liability for political aspirants. When former president Gerald Ford died last month, it brought up memories of the most famous headline in New York newspaper history: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. Ford never actually said those words, but in the eyes of many New Yorkers, that hostility has barely faded over the last thirty years.

Not coincidental to this dry spell, say many experts, is the persistent anti-urban bent of the federal government over the last several decades, which has drained New York of resources and made being from the Northeast a political liability for political aspirants. When former president Gerald Ford died last month, it brought up memories of the most famous headline in New York newspaper history: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. Ford never actually said those words, but in the eyes of many New Yorkers, that hostility has barely faded over the last thirty years.

Suddenly, though, New Yorkers are banging at the doors of the White House - and, perhaps just as significantly, are in control of some of the most powerful positions in Congress.

Is this simply a coincidence, the confluence of several oversized personalities at the same time and place? Or does it reflect New York's return to prominence in national politics? Either way, what would New York get out of having one of its own in the White House?

THE FOUR HORSEMEN

Among political circles it is considered a bad strategy for a candidate to announce that he is running for president until he has spent several months - or years - campaigning, seeing how it feels and deciding whether he really has a shot. No New Yorker, then, is officially running yet for president in 2008. But at least four are "considering it":

Michael Bloomberg: Democrat-turned-Republican Mayor Michael Bloomberg says he is not running for president, but his name is always included on the list of New York candidates as an independent who will appeal to voters looking for competence over party affiliation. This is partially because the mayor and his senior staff seem to go out of their way to encourage such talk. Bloomberg has said he would make a great president as long ago as 1997, and his close advisors openly discuss him as a viable candidate. Bloomberg himself recently pointed out that he could spend more of his own money in a presidential run than many major party candidates could raise, shortly before he dressed up like Bruce Springsteen at a staff holiday party and sung his own version of "Born to Run." But when asked about his intentions, Bloomberg just smiles and asks what he has to do to convince people that he's not interested.

Hillary Clinton: Polls show Senator Hillary Clinton as the favorite for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 2008. She hasn't officially announced her candidacy,  but cynics say it started in 2000, when Clinton moved to New York, switched loyalties from the Cubs to the Yankees, and was elected senator. Since then, she has amassed a huge pool of money, and is enlisting the help of well-respected consultants for her undeclared campaign. Hers is one of the most-recognized names in American politics. One of Clinton's most cited political liabilities is that her reputation as an angry liberal is off-putting to important moderate Republican voters - so she spent $36 million on her 2006 Senate reelection campaign, making sure to win over upstate Republicans.

but cynics say it started in 2000, when Clinton moved to New York, switched loyalties from the Cubs to the Yankees, and was elected senator. Since then, she has amassed a huge pool of money, and is enlisting the help of well-respected consultants for her undeclared campaign. Hers is one of the most-recognized names in American politics. One of Clinton's most cited political liabilities is that her reputation as an angry liberal is off-putting to important moderate Republican voters - so she spent $36 million on her 2006 Senate reelection campaign, making sure to win over upstate Republicans.

Rudolph Giuliani: After September 11, 2001, former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani became a national star, his troubled legacy lost among the accolades as a hero and big city crime fighter. He may be hampered in the Republican primary, however, by his New York-like views on abortion, gay rights, and gun control, the public turmoil in his personal life, or his reluctance to abandon a lucrative career in the private sector. Giuliani's own concerns about these political liabilities were dragged through the press recently when private campaign documents were leaked to the Daily News. Giuliani's ability to inspire strong feelings is reflected in one high profile endorsement he has already received for next year's primary: Congressman Charlie Rangel said that he would love for the former mayor to be the Republican candidate so he could attack Giuliani's record as mayor. As a running mate for Giuliani, Rangel suggested his disgraced former police commissioner, Bernard Kerik.

George Pataki: Former Governor George Pataki is not officially running for president just yet; his spokesperson says that he's "weighing the options with his family." But the former governor has quit his job; visited Baghdad and then gone on national television to discuss what he learned; and lavished attention on the states where success in presidential primaries can light a fire under a campaign (he visited Iowa no less than nine times in 2006, and raised money for Republican candidates in New Hampshire). Pataki's efforts have been met with near-universal mockery. Conservatives attack his record on taxes as governor, and his 12-year term in Albany is widely described as a time of gridlock and dysfunction. The best chance most political observers give him is a shot at latching onto a more viable candidate's ticket as the vice presidential candidate.

It is considered very unlikely that all of these candidates will make a serious attempt at the White House. In December, Newsday actually printed the odds that it gave to each candidate lasting until the presidential nominating committees next summer. Clinton was given the best odds (one in three), followed by Giuliani (one in 10), Pataki (one in 50), and Bloomberg (one in 150).

In theory, at least, the 2008 presidential race could come down to a contest between three New Yorkers - a Republican, a Democrat, and an independent. But, to play with Newsday's numbers, the chances of that happening are 0.07 percent at best.

NEW YORK AND THE PRESIDENCY

New York formed a special relationship with the office of the president immediately, when George Washington was sworn in as the first person to hold the office at Federal Hall on Wall Street in 1789. Of course, the first president also advocated burning the city to the ground during the Revolutionary War. The city on the Potomic that took his name, some New Yorkers would argue, has adopted that proposal as the basis for its attitude in dealing with the city on the Hudson in recent decades.

Four presidents were actually born in New York State - Martin Van Buren, Millard Fillmore, Teddy Roosevelt, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt - and at least one more was elected as a New Yorker (Grover Cleveland, who was born in New Jersey, but was raised in Buffalo and eventually became governor). The city was the site of Abraham Lincoln's famous 1860 speech that helped propel him into office, as well as six national conventions. Fourteen presidents have lived in New York City at some point. Two are around today: Bill Clinton, who opened an office in Harlem after leaving office, and Ulysses S. Grant, who is buried on Riverside Drive.

The City's Declining Political Fortunes

Since Franklin Delano Roosevelt died in office in 1945, New Yorkers have been kept out of the White House - and have seen their clout in national politics diminish significantly. In part this is a function of population - both the city and the state make up a relatively smaller proportion of the country's population than they did during the Roosevelt years. Most older cities face the same dilemma. While this does reflect population shifts that began after World War II when the creation of the national highway system led to the birth of the suburbs, there are other causes as well. Politicians see vying for the votes of suburban swing voters as a better use of their energy, knowing that urban areas are full of predictably Democratic voters. There has also been a shift in the prevailing ideology of American politics away from the liberalism associated with New York. Few national politicians want to be tarred as a "Northeastern Liberal."

New York does remain central, however, in the national fundraising scene. New York City-area residents gave more money to national political candidates in 2004 than any other metropolitan area; only the District of Columbia gave more in 2006.

IS NEW YORK BACK?

With New York looking to contribute more than just funding in the 2008 presidential election, politicos and policy wonks are discussing whether the city and the state are regaining central roles in national politics.

With New York looking to contribute more than just funding in the 2008 presidential election, politicos and policy wonks are discussing whether the city and the state are regaining central roles in national politics.

"There's no question that New York has come back from the political wilderness," said political consultant Hank Sheinkopf. He argues that the stereotype that New York is out of step with the rest of the country is inaccurate, but believes that 9/11 - not a realization that New York is not a "bastion of left-wing insanity" - is the driving force behind the city's improving political fortunes.

Presidential hopefuls aside, New York's voice in Washington has recently gotten much louder. Senator Charles Schumer is credited as one of the masterminds of the Democratic takeover in both houses of Congress, making him an incredibly influential member of the newly empowered Democratic Party. With Democratic control over chairmanships of committees - one of the most important markers of congressional clout - New Yorkers have gained immensely. Perhaps most notable is Representative Charles Rangel's rise to the top of the House Ways and Means committee, arguably the most important committee in the house. Other key committee assignments are:

• Nydia Velazquez's new role as head of the house's Small Business Committee;

• Schumer's place on the senate's Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee;

• Senator Clinton's assignment on the Health, Education Labor and Pensions Commitee

• Representatives Gary Ackerman, Gregory Meeks, Joe Crowley, Vito Fosella, Carolyn Maloney and Velazquez's seats on the the Financial Services Committee.

• and Jerrold Nadler and Anthony Weiner's positions on the house Transportation Committee.

If the shift in power from Republicans to Democrats has made New York much more powerful, the factors that have reduced its power have hardly disappeared. New York State is now the country's third most populous behind California and Texas. By the time of the next census, it is expected to fall behind Florida as well. Doug Muzzio, a professor of public affairs at Baruch College, believes that "the sun has set" on the era when big cities drove the country's political agenda.

But what about all those presidential candidates? Muzzio doesn't see them as evidence of any shift.

"I think it has more to do with the particular people rather than some larger contextual change about New York and its place in American politics," he said. "I don't want to sound like a professor, but it's not systemic. It's idiosyncratic."

WHAT'S IN IT FOR US?

New York enjoyed its best relationship with Washington in the 1930s and 1940s, when Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia joked that Roosevelt's White House was "no further than the Bronx." The president acknowledged his soft spot for the mayor and the city. "[LaGuardia] comes to Washington and tells me a sad story. The tears run down my cheeks and tears run down his cheeks and the first thing I know, he Has wangled another fifty million dollars," he is quoted as saying in Thomas Kessner's definitive biography of LaGuardia.

Most political observers acknowledge that the city will not see another era like that, when federal money was used to build the Triborough Bridge, LaGuardia Airport, and the Lincoln Tunnel.

But the federal government's affects New York City on every issue from education to mass transit to health care to housing to immigration.

Bringing a uniquely New York perspective to these issues would almost certainly benefit the city, said Gerald Benjamin, dean of liberal arts and sciences at SUNY New Paltz.

"It would be a convergence of a New York presidency with the placement of New York congressional leaders in key positions that would be critically important," he said. "We've already begun to see that happening."

As New York's representatives grab more influential committee posts, they are eying pet projects and issues that have not gained traction to this point. On her first day as chair of the small business committee, Nydia Velazquez introduced a bill that would encourage bodegas to carry healthier foods in low-income neighborhoods. Jerrold Nadler, who sits on the transportation committee, will likely step up his decades-long pursuit of a freight tunnel under New York Harbor.

The main area where New York seems to be able to swing its political clout immediately is on homeland security funding. Since 9/11, New York officials have complained that this money has been used as political pork, " spread across the country like peanut butter," as Mayor Bloomberg put it in testimony before Congress last week. There have been indications that changes are in the works, though. The Department of Homeland Security announced recently that New York and other major urban areas will get 55 percent of the $747 million pool of homeland security grants, and that New York and New Jersey will get the lion's share of a separate pool of grants for port and rail security.

The main area where New York seems to be able to swing its political clout immediately is on homeland security funding. Since 9/11, New York officials have complained that this money has been used as political pork, " spread across the country like peanut butter," as Mayor Bloomberg put it in testimony before Congress last week. There have been indications that changes are in the works, though. The Department of Homeland Security announced recently that New York and other major urban areas will get 55 percent of the $747 million pool of homeland security grants, and that New York and New Jersey will get the lion's share of a separate pool of grants for port and rail security.

New York's congressmen feel more confident about getting things done in Washington after November's elections. But Congressman Nadler says the delegation's efforts have limits if they don't have an ally in the White House.

"We have more power. We have more influence. But we don't control," he recently told the New York Sun.

While some changes in Washington could be tracked through hard numbers, experts also predict that having a president from New York would inspire a major change in the attitude of the federal government. This would not necessarily be quantifiable, but would be reflected in the overall approach that the federal government took on all domestic issues. "Simply a recognition of the problems that New York City and other urban jurisdictions face, whether it's transportation, infrastructure, schools, etc., any one of those issues would be salient to any of the four" presumed candidates, said Muzzio.

Muzzio and others have pointed out that a Democratic president would be more likely to form a close alliance with the city's overwhelmingly Democratic congressional delegation. But in at least one way it wouldn't matter which party the president came from.

"You won't have a national government run by people who question whether New York is part of the United States," said Benjamin.

Â

Cracking Down on Corruption

The crowd clapped when Governor Eliot Spitzer announced in State of the State Speech last week that he would seek to reform Albany. But cynics could easily note that applause is cheap.

The crowd clapped when Governor Eliot Spitzer announced in State of the State Speech last week that he would seek to reform Albany. But cynics could easily note that applause is cheap.

Sitting behind Spitzer as he spoke was Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, under federal investigation for misusing state funds. Joining Bruno on the podium was Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. Together, the two men have set much of the tone in Albany for the last 12 years and preside over a legislature where two members are under criminal indictment, two have had recent run-ins with the law for assault, and numerous others have left under a cloud.

Equally worrisome to many reformers are actions that are perfectly legal. Lax regulations and violations of what laws that do exist have contributed to Albany’s reputation as one of the worst state capitals in the nation.

“You read in every newspaper how many people have been investigated and indicted and convicted,” said Suzanne Novak, deputy director of the Brennan Center for Justice, “There are many factors that go into this,” Novak said but, for starters, the state does not have strict enough laws and does not adequately enforce those laws that it does have.

Eliot Spitzer came to Albany promising to change that. And in his first days in office he began taking concrete steps to do that. But can he really succeed?

A CULTURE OF CORRUPTION

Since the Brennan Center issued a report in 2004 which branded New York’s legislative process the most dysfunctional in the nation, the litany of woes facing state government have become familiar. Three men -- the governor, the speaker and the Senate majority leader -- control the legislative process with individual members often barely knowing what they are voting on. State legislators are allowed to have outside income and even keep it secret – as Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver does – as long as it does not conflict with their public duties. The legislature allocates tens of million of dollars for member items—pet ventures or pork barrel schemes—with little to no public scrutiny.

A redistricting process controlled by the legislature guarantees that lines will be drawn to protect incumbents, giving jobs for life to even the most mediocre Assembly members and state senators. Candidates assured of re-election rake in contributions and use the money for luxury cars and sometimes even legal fees. The state's system of selecting judges has been ruled unconstitutional. New York has more lobbyists per legislator – 20 for each one – than any other state in the county, according to the Center for Public Integrity.

And the rules here appear looser than in many other states. For example, even though he pleaded guilty to a felony, former State Comptroller Alan Hevesi will get to keep most of his state pension. The Albany blog Capitol Confidential contrasted that with Massachusetts, where former House Speaker Thomas Finneran was “almost certain” to lose his $30,000 a year pension after pleading guilty to obstruction of justice charges.

The Albany culture, former State Assembly member Nelson Denis wrote this month, features “a bipartisan Favor Bank built on state contracts, the disposition of state lands, and patronage spending by various public authorities. Every year, Democrats and Republicans posture over their differences, while tacitly collaborating to accommodate the permanent interests of each.”

A MOVE FOR REFORM

In his first days in office, Spitzer tried to take on some of these practices. He issued five executive orders aimed at ethics, stressed government reform in both his inaugural speech and State of the State address. And Attorney General Andrew C Cuomo also sounded the theme

Here is some of what they will do:

Set standards for state workers: In his first day in office, Spitzer issued an executive order barring state employees from accepting gifts designed to influence their decisions, from using state property for personal use, from hiring relatives, and from taking jobs as lobbyists for two years after leaving state government.

Limit the role of politics in state government: Another executive order would bar some state employees from making campaign contributions to the governor and lieutenant governor and would not allow officials to ask prospective employees and contractors about their political affiliations. It also bans elected officials and candidates from appearing in publicly funded ads for state agencies. So, Eliot and Silda Wall Spitzer will not reprise Libby and George Pataki’s roles in “I Love New York” ads.

Regulate campaign finance: In his State of the State speech, Spitzer announced he would submit a package of measures to limit campaign contributions in the state, restrict donations from lobbyists and corporations and begin steps toward instituting public financing of campaigns.

Change the redistricting process: Spitzer said he would submit legislation to establish an independent nonpartisan commission to draw legislative districts in New York. (The next redistricting would follow the 2010 census.) “Until this happens,” he pledged, “I will veto any proposal that reflects partisan gerrymandering.”

Streamline the courts: The governor said he would submit two constitutional amendments aimed at improving New York’s courts – one to consolidate the patchwork of courts in the state’s judicial system and the other to implement a merit process for the selection of judges.

Review member items: Attorney General Andrew Cuomo has said he would go over the 6,000 expenditures on the list to make sure they met the standards for spending public funds.

WILL IT WORK?

Such proposal are “ overwhelmingly matters of common sense that would shake [Albany] to its very foundations,” the Daily News said in an editorial, adding Spitzer’s reform proposals are “ambitious and screwed on straight.”

And many believe they will have an effect. “It’s hard to get things through in Albany, but we now have someone who’s going to push for change,” Novak said. “As attorney general, Eliot Spitzer did not tolerate people not obeying the law.”

But he faces an exceedingly difficult task. Already people were seeing danger signs. Novak notes, that at the same time they applauded Spitzer’s calls for reform, members of the Assembly adopted the same old rules that have long guided their way of doing business. And Senate Republicans again selected Joseph Bruno as their leader – even though he is under federal investigation. Only one GOP senator, John Bonacic of New Paltz, publicly protested the move. "He's been damaged and this ongoing investigation will impair his ability to lead," Bonacic told a local paper. "He should step down as majority leader, even if it's temporarily, until the cloud is removed."

Cleaning up Albany is “a lot harder than cleaning up Wall Street,” former State Senate Seymour Lachman has said because, while the financial world is “answerable to a market of investors, there’s almost no accountability in the State Legislature.”

What can Spitzer do “with 211 legislators who have such a fine sense of perversity that they applaud when he vows to do away with the very basis of their jobs,” asked Schenectady Gazette columnist Carl Strock. “I don’t think you can do much with a gang like that. They will pat you on the pat and pump your hand and proclaim themselves friends of reform all the way to the next wine and cheese reception where they will shake down lobbyists from the hospital and nursing home industry, the tobacco industry, the teachers’ union or whatever other outfit has big money to hand out.”

A ROGUE’S GALLERY

As lax as the laws on state government are, some New York politicians have managed to break them. Forget the tough streets of New York City, say some pundits, the hallowed halls of the Capitol boast the state’s highest crime rate.

Here are some of those who have been convicted or indicted.

--Alan Hevesi: The state comptroller, a former member of the state assembly and city comptroller, was coasting to re-election and a seemingly long career in office last fall when his little known Republican opponent got a tip that Hevesi was using a state employee to drive around his ailing wife. Hevesi reimbursed the state, apologized and managed to win re-election, but he could not stave off opposition from one-time ally Spitzer and the feeling that a man who defrauded state government is probably not the best person to insure other public official and agencies spend public money properly. Hevesi resigned three days before Christmas, pleading guilty to a felony charge but probably avoiding any jail time. The legislature will appoint a replacement, although Spitzer is expected to play a major role in the process.

--Alan Hevesi: The state comptroller, a former member of the state assembly and city comptroller, was coasting to re-election and a seemingly long career in office last fall when his little known Republican opponent got a tip that Hevesi was using a state employee to drive around his ailing wife. Hevesi reimbursed the state, apologized and managed to win re-election, but he could not stave off opposition from one-time ally Spitzer and the feeling that a man who defrauded state government is probably not the best person to insure other public official and agencies spend public money properly. Hevesi resigned three days before Christmas, pleading guilty to a felony charge but probably avoiding any jail time. The legislature will appoint a replacement, although Spitzer is expected to play a major role in the process.

--Joseph Bruno: The state’s most powerful Republican and the majority leader of the State Senate, Bruno announced last month that he is under federal investigation for steering state money to a businessman and friend who showered the majority leader with money and favors. So far no indictments have been issued.

--Joseph Bruno: The state’s most powerful Republican and the majority leader of the State Senate, Bruno announced last month that he is under federal investigation for steering state money to a businessman and friend who showered the majority leader with money and favors. So far no indictments have been issued.

-- Efrain Gonzalez: The state senator from the Bronx, a Democrat, faces criminal charges for having spent some $400,000 in state funds for his own uses, including running his cigar company, improvements to residences, Yankees tickets and jewelry. Gonzalez allegedly funneled state money to Pathways for Youth, a Bronx charity and then took money from the charity. Although he was under indictment on similar charges in November, voters re-elected him.

Efrain Gonzalez: The state senator from the Bronx, a Democrat, faces criminal charges for having spent some $400,000 in state funds for his own uses, including running his cigar company, improvements to residences, Yankees tickets and jewelry. Gonzalez allegedly funneled state money to Pathways for Youth, a Bronx charity and then took money from the charity. Although he was under indictment on similar charges in November, voters re-elected him.

--Brian McLaughlin: Last fall, McLaughlin, then an assembly member from Queens and president of the New York City Central Labor Council, was indicted on 43 charges that could send him to jail for decades. The 186-page indictment alleges that McLaughlin took some $2.2 million from the government, unions, contractors and even a Little League team and used the money to finance such items as home renovations, country club membership and marina fees, school tuition, rents and other items. About 10 months before he was charged, McLaughlin had announced he would not seek re-election to the legislature and he has since been relieved of his labor post, at least for the time being.

--Brian McLaughlin: Last fall, McLaughlin, then an assembly member from Queens and president of the New York City Central Labor Council, was indicted on 43 charges that could send him to jail for decades. The 186-page indictment alleges that McLaughlin took some $2.2 million from the government, unions, contractors and even a Little League team and used the money to finance such items as home renovations, country club membership and marina fees, school tuition, rents and other items. About 10 months before he was charged, McLaughlin had announced he would not seek re-election to the legislature and he has since been relieved of his labor post, at least for the time being.

--Diane Gordon: The Democratic assemblywoman from Brooklyn faces criminal charges for seeking a $500,000 bribe in return for helping a developer get a $2 million city lot. The bulk of the bribe was to be a $500,000 home that was not even in Gordon’s district. Although she is awaiting trial on charges that could send her to jail for up to 15 years, she was re-elected in November.

--Diane Gordon: The Democratic assemblywoman from Brooklyn faces criminal charges for seeking a $500,000 bribe in return for helping a developer get a $2 million city lot. The bulk of the bribe was to be a $500,000 home that was not even in Gordon’s district. Although she is awaiting trial on charges that could send her to jail for up to 15 years, she was re-elected in November.

--Ada Smith: After several instances of erratic and even violent behavior, the state senator from Queens was charged last year with throwing hot coffee at an aide’s face. Smith was found guilty of the charges and unlike most Albany offenders actually lost her bid for re-election. In a rare slap at an incumbent, voters in her district – apparently fed up with being represented by someone tabloids tagged â€the wild woman of Queens” – elected Shirley Huntley to replace Smith.

--Ada Smith: After several instances of erratic and even violent behavior, the state senator from Queens was charged last year with throwing hot coffee at an aide’s face. Smith was found guilty of the charges and unlike most Albany offenders actually lost her bid for re-election. In a rare slap at an incumbent, voters in her district – apparently fed up with being represented by someone tabloids tagged â€the wild woman of Queens” – elected Shirley Huntley to replace Smith.

--Clarence Norman: The onetime leader of the Brooklyn Democratic Party, State Assemblymember Norman has faced an array of criminal trials. In 2005, he was convicted on three felony counts and one misdemeanor for soliciting and receiving illegal campaign contributions. Although voters had stuck with Norman, the conviction forced him to give up his seat. He could still face additional charges, springing from the alleged sale of judgeships in Brooklyn. Norman’s replacement in the State Assembly is a colleague of his father’s.

--Clarence Norman: The onetime leader of the Brooklyn Democratic Party, State Assemblymember Norman has faced an array of criminal trials. In 2005, he was convicted on three felony counts and one misdemeanor for soliciting and receiving illegal campaign contributions. Although voters had stuck with Norman, the conviction forced him to give up his seat. He could still face additional charges, springing from the alleged sale of judgeships in Brooklyn. Norman’s replacement in the State Assembly is a colleague of his father’s.

--Kevin Parker: The state senator from Brooklyn was accused of assaulting a traffic officer in 2005. The incident was one in a series of outbursts by Parker, who plead guilty to a misdemeanor and agreed to take anger management classes. In the meantime, he won re-election.

--Kevin Parker: The state senator from Brooklyn was accused of assaulting a traffic officer in 2005. The incident was one in a series of outbursts by Parker, who plead guilty to a misdemeanor and agreed to take anger management classes. In the meantime, he won re-election.

-- Roger Green: In 2004, the Brooklyn State Assembly member resigned his post after pleading guilty to illegally accepting rides from a state contractor and then accepting “reimbursement” from the state for the free transportation. But the following fall, with little serious opposition, Green won his old seat back. Now, though the long-time legislator is again out of office, having given up his Assembly seat in 2006 to make an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Congress.

Roger Green: In 2004, the Brooklyn State Assembly member resigned his post after pleading guilty to illegally accepting rides from a state contractor and then accepting “reimbursement” from the state for the free transportation. But the following fall, with little serious opposition, Green won his old seat back. Now, though the long-time legislator is again out of office, having given up his Assembly seat in 2006 to make an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Congress.

--Guy Velella: In 2002, the longtime and powerful Republican state senator, whose district straddled the Bronx and Westchester, was indicted on bribery charges. Despite the accusations, Velella, like so many other discredited incumbents, handily won re-election boosted by such luminaries as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. The senator finally had to step down in 2004 after pleading guilty to charges that he illegally took money from people seeking state contracts to paint bridges and went off to jail. But controversy continued as a little known city panel initially let him leave jail early – a decision eventually overruled after intervention by Bloomberg.

--Guy Velella: In 2002, the longtime and powerful Republican state senator, whose district straddled the Bronx and Westchester, was indicted on bribery charges. Despite the accusations, Velella, like so many other discredited incumbents, handily won re-election boosted by such luminaries as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. The senator finally had to step down in 2004 after pleading guilty to charges that he illegally took money from people seeking state contracts to paint bridges and went off to jail. But controversy continued as a little known city panel initially let him leave jail early – a decision eventually overruled after intervention by Bloomberg.

Â

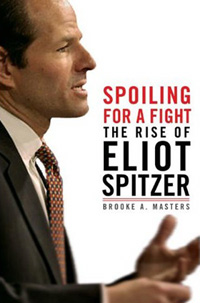

Eliot Spitzer, Governor

Gotham Gazette’s Reading NYC Book Club recently met with Brooke Masters, a reporter for the Financial Times whose book, Spoiling for a Fight: The Rise of Eliot Spitzer, details Eliot Spitzer’s career as New York State Attorney General. Masters talked about Spitzer’s new job as governor of the state; he was inaugurated on January 1, 1007. Below is an edited transcript.

Gotham Gazette: In the time covering Spitzer and in your time writing the book, what did you learn that you think it's important for people to know about Eliot Spitzer?

Gotham Gazette: In the time covering Spitzer and in your time writing the book, what did you learn that you think it's important for people to know about Eliot Spitzer?

Brooke Masters: This is a guy who is extraordinarily ambitious...[but] unlike other politicians I've run into who are ambitious because they want to be somebody, he's ambitious because he wants to do something. That's going to make him an interesting governor. He's going to put himself on the line and risk losing... That's what made him such a controversial and successful attorney general – he would take on cases that were not obvious winners, and that might be on the edge and controversial, because he truly thought that what he was doing would accomplish a goal that he had set for his office, or were a way he saw of improving society.

SPITZER, ISSUE BY ISSUE

Gotham Gazette: Tell us how Spitzer's experience with issues as attorney general might indicate what his priorities or approach might be as governor.

White Collar Crime

Gotham Gazette: A good place to start is his fight against white-collar crime on Wall Street. Is there any obvious way Spitzer would continue this campaign as governor? Does the office have duties of oversight on Wall Street?

Brooke Masters: Well, that's what made him famous. There are very few attorneys general that people can name, even their own, and Spitzer is famous pretty much around the country because of the white collar crime cases.

Spitzer knows that simply screaming at people isn't going to work. Whether he can avoid screaming at people, I don't know.

As governor he would appoint the folks who are in charge of the banking department, and the folks who are in charge of the insurance department, and have an overall policy role. He wouldn't be doing enforcement cases, but he would have some role in setting up rules on how banks and insurance companies treat their customers, and what the disclosure rules are. So sort of on the margins he would have an effect on that.

The Wall Street cases were a part of Spitzer's view – which he is happy to go on at length about, and does at the drop of a hat – about economic opportunity. His family went from nothing to fabulously wealthy in one generation. He believes in capitalism, he believes in the markets, and believes that government's role is making sure those opportunities are there for everybody. You're more likely to see him as governor emphasizing ways of encouraging economic opportunity in a less statist role. I think he's going to try to get away from the traditional Democratic style. Although he's probably in favor of raising the minimum wage and things like that, he will probably focus on trying to find ways to foster economic opportunity and make the markets fair.

Public Education

Gotham Gazette: What else is on Spitzer's list?

Brooke Masters: Obviously, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity solution in relation to the funding of New York City schools is a big issue. He's been given a gift, because the Court of Appeals says he only has to spend $2 billion. But he himself said it would take $4 to $6 billion. I think he'll try to come up with some compromise numbers, and try to use that in a motivating way –- there will be a caveat that a lot of the money will have to go to unusual programs like the small schools that Bloomberg has been doing.

He's not a voucher guy, but he is in favor of charter schools – that there should be competition between regulators, there should be competition between schools, and that ultimately choice is what leads to improvement, and that people should be allowed to vote with their feet. That is part of his whole marketplace idea of the world.

Medicaid

Another priority is Medicaid. Anybody who follows the state budget knows that Medicaid is the fastest growing and largest part of the state budget. It also contributes to high property taxes, because the local governments also kick in for Medicaid...If Spitzer could bring down Medicaid costs, he'll have lots of money to do other things, but he'll also win points with the suburbanites who are paying high taxes.

Another priority is Medicaid. Anybody who follows the state budget knows that Medicaid is the fastest growing and largest part of the state budget. It also contributes to high property taxes, because the local governments also kick in for Medicaid...If Spitzer could bring down Medicaid costs, he'll have lots of money to do other things, but he'll also win points with the suburbanites who are paying high taxes.

He has made a no new taxes pledge, which was an interesting choice for a Democrat, particularly one who was running so far ahead in the polls. I don't think he had to; he's doing it because he believes it. If he solves Medicaid, he can bring taxes down without hurting other things.

Gotham Gazette: Has he given an indication as to how he thinks the Medicaid problem should be solved?

Brooke Masters: He talks a lot about streamlining and technology. He got really excited the other day about trying to improve hospital information technology, so when you go to a hospital all the other tests that you've had at the six other hospitals and doctor's offices you've been to will pop up, so they won't retest you for the 25 things that you've already been tested for. Particularly for Medicaid, which is paying those bills, if you could even cut down on a fifth of the tests, it would actually amount of substantial savings.

He's also talked about trying to expand primary care to cut down on emergency room visits. Everybody likes to talk about wouldn't it be nice if there were fewer emergency room visits. But I think that he's actually interested in setting aside money to do it.

Albany Reform

Gotham Gazette: One of the things that Spitzer mentioned as a priority during his campaign for governor is so-called Albany reform – fixing how the state government actually works. Some of his critics have said that as attorney general he had the chance to deal with this but did not. Do you think that's a valid criticism?

Brooke Masters: I think it's unfair to say that Spitzer won't take on Albany simply because he hasn't taken on Albany. The attorney general, like any public official, has limited resources. And he did clearly choose to do Wall Street, rather than Albany.

Also, if you look at the staff he gathered, he did not have a particularly strong grounding in Albany. Public corruption cases require above all really good informants, really good sources, and a really good understanding of exactly how business is done. Taking it on as a prosecutor means you have to put together cases, and that is particularly tough.

As governor he might have the clout -- as someone who just won the election with a large margin of victory -- to pass lobbying reform, and agency reform, and commission reform as legislation.

Bob Zane: Eliot Spitzer has been on record as critical of public authorities. Do you think he will try to get more control and get them to be more efficient?

Brooke Masters: Yes. The authorities control so much money. If you are going to try to get the state budget under control and refocus it, you have to get the authority money or you're never going to be able to do it. I don't know if it will work, but I wouldn't be surprised to see that on his agenda in the first two months.

Henry Stern: Doesn’t he appoint the members of the authorities?

Brooke Masters: Most of them do not serve at the pleasure of the governor, so they are going to be holdovers from former Governor George Pataki for quite a while. There's a lot of skullduggery being talked about – people resigning so that Pataki can re-appoint them now, so that Spitzer won't be able to appoint their own people. There's a long history of doing that in New York.

Gotham Gazette: One goal that Spitzer put on his agenda was to reform the redistricting process, and on the uber-technical side of things, do you think he’ll be successful in that? You’ve already touched on sort of what his working relationship might be with the legislature, but do you think he actually will be able to put his foot down on that?

Brooke Masters: I think he’s going to try. But I think he's going to do lobbying reform and campaign finance reform and authority reform first. They're all an easier sell. None of the others put the legislature at risk of their jobs.

Gun Control

Brooke Masters: Gun control was Spitzer's big loss. It’s going to be interesting because he worked with Andrew Cuomo on this and they both completely failed in the late 1990s. Cuomo in particular says he's still interested in pursuing it.

Brooke Masters: Gun control was Spitzer's big loss. It’s going to be interesting because he worked with Andrew Cuomo on this and they both completely failed in the late 1990s. Cuomo in particular says he's still interested in pursuing it.

In the 1990s, New York was getting all these illegal guns from Virginia, because people would go to Virginia, buy a dozen guns – there are very loose rules there – and sell them here. Spitzer's theory was that the gun manufacturers knew full well which retailers were selling to lots and lots of people who were using the guns in crimes, and that if they just cut off a few of the bad dealers it would cut down on illegal gun crime.

He brought a lawsuit against the gun manufacturers arguing that they were creating a public nuisance by putting illegal guns on the streets. It was absolutely torched by the courts. They were not interested in this theory; they thought it was ridiculous.

It is a classic Spitzer thing to do. He takes this law – public nuisance – which is generally used for environmental cases and noise, and tries to apply it to something completely different, in this case illegal guns. It didn't work, but you might see Cuomo come back at that issue somehow. He and Spitzer both remain convinced that it was the right thing to do.

But he and Cuomo also tried to work with gun companies to see if they could get them to go along and create a screening program for retailers. It will be interesting to see if that comes back.

Gotham Gazette: As governor he might find fertile ground to work with that, since Bloomberg is so into combating illegal guns right now.

Brooke Masters: Exactly. I could see him working with Bloomberg on this. He and Bloomberg want to work together on a lot of stuff. They like one another, and they have a similar worldview. I think you'll see a lot of Bloomberg-Spitzer alliances on things.

But if you ask Spitzer to make a list of the five things he's going to do first, illegal guns are not there – as opposed to Cuomo. Spitzer's interested in crime, but he recognizes that he doesn't have that much hands-on authority on crime as governor; that's what the district attorneys and police departments and localities do.

Economic Development

Brooke Masters: Economic development upstate is also an issue. Basically we've got depressed Ohio everyplace north of Albany. Until that part of the state stops being completely depressed, that will be one of his priorities because it puts a drag on the whole rest of the state.

He wants to fix workers compensation, which seems like a real technical issue. But it turns out that New York has an extraordinarily expensive workers compensation program – the eighth most expensive in the nation in terms of the premiums that employers pay. But it is 49th in terms of payouts. Somewhere between the high premiums and the low payouts, a lot of money is disappearing. Nobody knows exactly what's wrong, but something must be. Spitzer is trying to solve that problem because he will win points with business for cutting their costs, but not hurt workers. If you eliminate the administrative costs, you could get the workers more money. It could be a win-win for everybody.

THE GOVERNOR AND NATIONAL ISSUES

Book Club Member: You've laid out a pretty strong state agenda that Spitzer is going to pursue. Do you have any sense for whether he is going to pick any national issues where he might be able to make an impact? There is a rumor in Washington that he is going to take some dramatic action in New York State that will affect the national debate on climate change.

Brooke Masters: He is already part of a lawsuit. There is a lawsuit by a lot of states arguing that the the Environmental Protection Agency is falling down on its job, and ought to be regulating carbon dioxide to stop global warming. The EPA and the Bush administration say they do not have the authority; the states say that under the Clean Air Act they have the authority and the duty to regulate anything that may affect human health. Much of the legal theory in that case was developed by staff lawyers in the New York Attorney General's Office, because it has the biggest environmental unit of any of the attorneys general offices. While it is Massachusetts that is the lead attorney, number two is New York.

Gotham Gazette: When will that case be resolved?

Brooke Masters: If they all agree, it could come out as early as March. If it's a close five to four, it will be June.

Spitzer is clearly interested in global warming. On the other hand, he has to be careful not to do too many things at once. Taking on the international debate on climate change while trying to fix Albany may not be the smartest move politically. I would be surprised if it is in his first six months to a year.

I think the other issue where he can reshape the national debate and affect New York at the same time is on Medicaid. If he can figure out a way to reform or fix Medicaid in a way that can be applied to other states, then he becomes a leading national figure in that debate.

CHANGING POLITICS IN ALBANY

Philip Angel: Spitzer was clearly on a mission when he was attorney general, while Governor Pataki was in the background. Now you have an ambitious attorney general and an aggressive governor in Spitzer and Attorney General Andrew Cuomo. Do you have sense of how those new dynamics are going to play out?

Brooke Masters: Cuomo and Spitzer are not, to put it mildly, the best of buddies. They have bad blood from the gun campaign, where Spitzer felt that Cuomo sold him up the river. On the other hand, Cuomo is dying to keep Spitzer's staff on, because frankly Spitzer attracted people to that office who would not ordinarily work for the New York attorney general's office. If Cuomo really wants to hit the ground running, he really needs to keep Spitzer's people on. So right now they have an alliance of convenience.

Henry Stern: They have united against Hevesi.

Brooke Masters: Yes, they have. Also, politically, they come at things the same way. They want to root out corruption in Albany. So if Cuomo – who has Albany connections and might actually be able to get some informers – works on arresting the bad people, while Spitzer works on reform from the legislation point of view, they might actually accomplish something and not get in each other's way.

If Cuomo spends his whole term wishing he were governor and proposing governor-type things, then there will be a lot of conflict.

But you can see there are going to be collisions. How much conflict there were be depends on whether Cuomo can pivot, and do what an attorney general does. If he spends his whole term wishing he were governor and proposing governor-type things, then there will be a lot of conflict.

Bob Zane: Do you think that Spitzer will be able to secure the cooperation of the business people in New York after prosecuting them?

Brooke Masters: I think it's complicated. Spitzer was obviously seen as the prohibitive favorite in the governor's race, but not a single business group endorsed Faso; not a single one gave him any money.

Henry Stern: Fear.

Brooke Masters: Could be straight fear. But if you talk to business people and you tell them you're not going to quote them, a lot of them say he's an ambitious guy who wants to accomplish things... maybe it would be a good idea to have him on our side. At least his job isn't going to be to be the enforcer anymore. And Spitzer is pretty good at knowing what his job is.

Upstate, there's a lot of optimism that, unlike Pataki, he actually cares about trying to fix upstate. In March, Spitzer made that comment that upstate New York is like Appalachia. The Republicans seized on that, saying it was offensive. But the response from the business community upstate was, "He's right. It is like Appalachia here. Would somebody please come fix it?"

The Wall Street folks don't like him, obviously, because he's made their lives miserable. But one of their theories is that he'll have credibility if he comes out and say we need X reforms to help make the stock exchange strong, since he's clearly not a patsy for the industry.

A COMBATIVE PERSONALITY

Gotham Gazette: One of the themes of your book is that Spitzer, while he's effective and energetic, is very combative and alienating. Can you talk about how well his personality will transfer from attorney general to governor?

Gotham Gazette: One of the themes of your book is that Spitzer, while he's effective and energetic, is very combative and alienating. Can you talk about how well his personality will transfer from attorney general to governor?

Brooke Masters: I think it will be really interesting. He's got to grow as a human being. He has been very much "My Way or the Highway." And that's not going to get him everywhere he needs to go.

On the one hand, everybody sort of believes that New York needs to change. All of the polls suggest that people voted for Spitzer because they thought he'd change things. In that way, his combative personality and his effort to shake things up could work in his favor. On the other hand, the big question is going to be when they get behind the scenes and get down to the negotiating, whether he can find a way to work with [Assembly Speaker Sheldon] Silver and [Senate Majority Leader Joseph] Bruno, or around them in a way to bring other legislators along. And I don't know that it works.

But the image that he gets angry and yells at people and gets out of control, I think it's overblown. He has more control over his temper than his critics would have you believe, but he uses it to scare the hell out of people.

That said, he is willing to tell people off, particularly people who don’t usually get told off. He doesn’t yell at secretaries, he doesn’t yell at waiters, he’s absolutely adored by the guys who drive him around. unlike many other politicians. He does yell at powerful people.

I think the big question is whether his head can control his natural instinct to be combative. That's going to be the big test for him – if he's going to be a great governor he's going to have to do that. I don't think you can really tell from his record whether he's going to pull it off. He's going to try. He knows that simply screaming at people isn't going to work. Whether he can avoid screaming at people, I don't know.

Bob Zane: Do you think that because he's wealthy, like Mayor Bloomberg, that he'll be more ethical, since you can't lobby him as much?

Brooke Masters: Maybe, because he's not going to be looking for a lobbying job at the end. On the other hand, some of the worst officials I have ever covered are wealthy people who think they are reformers, so they think the rules don't apply to them.

You could argue that Spitzer has that tendency. The campaign financing of his first two races in 1994 and 1998, the way he paid for it, it was not illegal, but it skirted every intention of the New York State ethics laws. Under these laws, you can put tons of money in your own campaign, but you can't fund your relatives' campaigns.

In Spitzer's family, the money is all with the dad. So Eliot Spitzer took out a private bank loan himself using some real estate he owned as collateral. That's legal; you can lend your own campaign money. But then his dad paid off the loan.

They were just going to get away with it until people starting asking questions about how he was paying off those loans on his salary. He finally had to say he would pay off his dad. It was not illegal because of the ways the laws were written. As for what the point of the law was – your dad can't buy you a seat – it was completely cheesy. That was one of these things where he was doing it for the good of America. You have to wonder if he's going to do it again. Hopefully he learned his lesson.

SPITZER AS GIULIANI, OR AS TEDDY ROOSEVELT?

Bob Zane: It sounds like he's a lot like Giuliani. Do you think that if he does a real good job, like Giuliani did, we'll eventually see him run for president?

Brooke Masters: Remember, Giuliani was washed up before 9/11. So let's not root for another terrorist attack, which is what made Giuliani famous.

But he's a lot like Giuliani, and in the last chapter of the book I say that Spitzer has two models he can follow as governor.

The first is Giuliani, which is sort of the "army of one." Giuliani accomplished a great deal, and pissed off a heck of a lot of people doing it, which limited his political future – at least until 9/11. But it is coming back to haunt him as he thinks about running for president.

The first is Giuliani, which is sort of the "army of one." Giuliani accomplished a great deal, and pissed off a heck of a lot of people doing it, which limited his political future – at least until 9/11. But it is coming back to haunt him as he thinks about running for president.

Giuliani is a good comparison because the two men have similar flaws. But Giuliani’s path – the I'm Right, You're Wrong, Do It My Way route – may be what the state needs. Giuliani would say, I came in as mayor and I busted heads in the unions and I busted the squeegee guys, and we did stop and frisk and alienated lots of people because someone had to save New York. And New York is now thriving. That's the model that you can really be nasty, combative, unfriendly, completely convinced of your own self-righteousness, and get stuff done. Barring an event like 9/11, it doesn't lead to long-term political success as a presidential candidate. But it might be good for the state.

The other model is Tom Dewey, who also was a completely self-righteous prosecutor, who also went into Albany and was completely combative. He vetoed something like one out of every three bills his first year. But within a couple years he realized he wasn't getting anything done and really changed his mode of operations. That's what I say when someone has to grow on the job. Dewey is a lot like Spitzer – bright, well educated, very driven white-hat prosecutor with wild national ambitions. He ran for president when he was still a prosecutor in New York, before he was governor. Dewey was able to pivot and work with the Democratic Party, and share credit.

If Spitzer does things like that, he can get lots done.

Gotham Gazette: You compare Spitzer to a lot of historical figures in New York politics. Who do you think he'd like to be compared to?

Brooke Masters: Oh, he loves being compared to Teddy Roosevelt. Spitzer has such a Teddy Roosevelt hang-up. He’s got Teddy Roosevelt pictures in his office, he quotes him – if you look at the transition New York Web site now there’s a Teddy Roosevelt quote. I mean he’s got total Teddy Roosevelt envy.

Spitzer has such a Teddy Roosevelt hang-up. He’s got total Teddy Roosevelt envy.

Admittedly, everybody’s got Teddy Roosevelt envy, because if you’re a middle-of-the-country person – which Spitzer would say he is, as a moderate Democrat — Roosevelt was the ultimate guy. He was a moderate Republican who broke with his party when his party did what he didn’t believe in. Roosevelt created the national parks, he took on big business, he revived antitrust law. Nowadays, he’s a hero.

But he was very, very unpopular at times during his early career because he was so combative. He was considered a complete nut. And I think Spitzer takes some comfort in that, too – that Teddy Roosevelt wasn’t always considered the hero.

Â