A Fractured Senate Takes on Mayoral Control of Schools

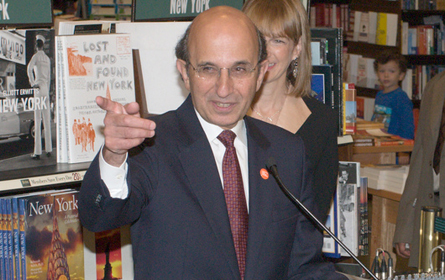

"It was never about power, it was about empowerment," said Sen. Pedro Espada Jr., on Thursday, having just switched back to the Democratic caucus to end a month-long power struggle between Democrats and Republicans in the state Senate. Democrats now have to deal with Espada in a position of power and also with the threat that any Democrat could follow in Espada's footsteps and break with party ranks whenever it serves them.

According to sources, had things gone just a little bit differently last week, Espada and his fellow "amigos," Sens. Carl Kruger, Ruben Diaz Sr. and Hiram Monserrate, could have been standing by the sides of the Republicans on Thursday.

A Democratic conference that was once led in a moderate way by Sen. Malcolm Smith, will now see its fate determined by its most extreme members. Some Democrats were devastated that their efforts to reach a power-sharing agreement with Republicans collapsed at the last minute. But now the Democrats find themselves part of a party ruled by the whims of Espada and his amigos, who on many issues tend to be more conservative than other Democratic members.

The splintering of the Democrats means bills with even a whiff of controversy could fail. Any progressive agenda Senate leaders had hoped to pass will now likely be stymied. Gay marriage is doomed this year, as is tougher rent regulation. But there is one contentious issue that Democrats have decided not to simply ignore: the governance of New York City schools.

Divided Democrats

With every passing hour it becomes clearer that the newly reshaped Democratic leadership structure will have to allow for more debate and dissension among its members. Individual senators have been empowered to speak out, bolt their caucus and, as Diaz demonstrated in the wee hours of Friday morning, vote against the wishes of their leadership.

Diaz voted with Republicans against a bill that would have approved mandatory surcharges for traffic offenses in Suffolk and Nassau counties. He later revealed that his vote was an attempt to get Republicans to oppose a half-percent sales tax increase for New York City that was backed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council. Diaz openly begged Republicans to join him. "Show me that you are my friends. Show me that I can work with you when we need each other," he said. The sales tax increase passed, but the message was sent: The amigos, and now likely other disenfranchised Democrats, have no master.

As a result, controversial legislation is not likely to come to a vote for some time. Gov. David Paterson has said he will not force a vote on gay marriage. Diaz vehemently opposes the measure.

Rent control legislation, including a measure that would have done away with vacancy decontrol, is now unlikely to see the light of day, because Espada opposes it.

During the Democrats’ Thursday press conference, reporters asked Espada about those measures. Espada answered that the Senate eventually would enact reforms that would allow members to bring legislation to a vote as long as they have enough support to pass the bill. (As things currently stand, the majority leader has all the power to determine which bills come to a vote.) But those changes have yet to be instituted, and it is still unclear if or when they will be.

Amending Education

Against a backdrop of confusion and some rancor, Democrats are expected to bring the Assembly's school governance bill to a vote when they return to session on Wednesday. The Assembly bill, proposed by Speaker Sheldon Silver in the Assembly and Sen. Frank Padavan in the Senate, essentially extends the current system with minor changes. The mayor supports it. In the Senate, some Democrats are expected to introduce amendments that the sponsors say would "enhance" that bill. Those amendments are designed to increase the public's input.

Three amendments have been introduced -- one by Smith, one by Sens. Martin Dilan and Bill Perkins, and the other by Sen. Shirley Huntley. Smith's and Perkins' bills would fund parental training to the tune of $1.6 million to help them be more involved in the school system. Huntley's bill would not fund training, leaving it instead to the borough presidents.

Perkins has been outspoken in his desire to see mayoral control truly overhauled. "I will do whatever I can to prevent the continuation of mayoral control as it existed," he recently told the Daily News.

Perkins' bill would place a two year term limit on members of the board of education. "Each voting member shall serve a two-year term," reads Perkins bill. Perkins' and Huntley's bills would require one of the mayor's appointments to be a parent of a special education student. Perkins', Huntley's and Smith's amendments would also establish a citywide council of the arts to increase arts education.

Sen. Jose Serrano has pushed for other measures to increase arts education. (To read a commentary on arts education by Serrano, go to "Saving Arts Education from Politics.")

A Divided Class

On school control, "there is a great diversity of thought amongst the members of the conference, to put it mildly," said Serrano, a former City Council member who voted in favor of mayoral control. He says he still stands by that vote would like to see school governance do more for arts education.

Serrano, who said on Monday he was still reviewing the proposed amendments, finds himself in a centrist position on school governance compared to his colleagues. Some Democrats want to leave mayoral control unchanged, while others, like Perkins, "say it has been a total disaster," Serrano said. A few Democrats have said they will do their best to stop the Assembly bill from becoming law.

There is talk that some of the senators who are most opposed to mayoral control want to see measures, such as the one proposed by Perkins, that would put term limits on the members of the educational policy panel and further reduce the mayor's power over school policy.

Austin Shafran, spokesperson for Senate President Malcolm Smith, said that Democratic members are "absolutely entitled to input into the final version of the bill." Shafran said that negotiations over the amendments are ongoing.

If Democrats in the Senate get behind the Assembly bill and then add amendments, it will almost certainly pass the Senate, as it has support from Republicans as well some Democrats. The amendments will face a stiffer test depending on what is negotiated and how Republicans feel about them.

A spokesperson for Padavan, who sponsored the Assembly's school governance bill in the Senate, said that the senator was focused on getting the Assembly bill passed and felt confident that it would succeed.

Even if the amendments pass the Senate, they cannot become law unless the Assembly returns to session and approves them. Assembly Speaker Silver made it very clear last month that he did not want to fiddle with the Assembly bill. If he has consented to the amendments in some sort of deal, they will almost certainly pass.

Shafran said that there had been discussion with the Assembly but declined to comment about what might result. He did say that the Senate is interested in "increasing parental input, which I think is something that we all can get behind."

A Whole New Bill?

For a number of senators, the proposed amendments, which were apparently negotiated with Bloomberg's office, do not go far enough. Some say the new amendments are intended to placate members who wanted to see more drastic changes.

Sen. Kevin Parker, who has sought greater reforms to school control, said on Monday night that a whole new bill is being negotiated. "Amendments might be how we get this done, but at this point I think we are negotiating a new bill," Parker, a frequent critic of Bloomberg, said.

Parker said that things have changed since last week, adding "My sense on mayoral control is that the landscape has dramatically changed because the Democrats retained control of the majority."

According to Parker, negotiations are continuing between Paterson, the Assembly and the Senate with "two points of real contention." The first, he said, is "whether the board on educational policy is an arbitrary board that basically serves as a staff meeting for the mayor or whether it has real input." The second, he said, is "whether the chancellor has the ability to arbitrarily close schools."

As for getting this all done by Wednesday, Parker did not make any promises: "If we can do it by Wednesday that is great but as I said to you about June 30, the deadline is arbitrary. Schooling is not being negatively affected." (June 30 was when mayoral control of schools officially expired.)

On Thursday before senators from both sides entered the Senate, Sen. Liz Krueger was asked about mayoral control. Although she generally supports the Assembly bill, Krueger would prefer to see increased parental input in city schools. But, as senators prepared to vote on legislation together for the first time in a month, she repeated her mantra on mayoral control. Despite the chaos and division that reigns over her party, despite the fact that she was uncomfortable with Espada, Krueger said as she had many times, with only a hint of exasperation, "We'll get it done."

The Mayor's High Stakes Test

For the next few days, New York City public school parents can vote in what the city's Department of Education bills as "the first public election in the U.S. to be held entirely online." By going to powertotheparents.org, parents can vote for members of community and citywide education councils, or more accurately, can advise their parent associations on who to choose for these posts. "Together let's improve our schools and make history," a public service announcement cheers.

Although the city has said at least 10,000 parents have voted, other signs point to a lack of interest. The city extended the voting deadline for a week to April 29. Of the 33 Community Education Councils, seven do not have enough candidates to fill all their seats, according to a report on WNYC, and only five parents showed up at a recent candidates' forum in the Bronx. One council member, Petra Peleon, likened serving on one to "being a bell that's ringing and no one's really responding."

The Community Education Councils represent the current incarnation of New York City's once powerful community school boards. Mayoral control of school, enacted by the state government in 2002, stripped them of their authority. Depending on who you believe, this has either created an efficient, accountable school system that has boosted student achievement or disenfranchised parents while doing little to truly educate New York City's more than 1 million public school students.

The Community Education Councils lie at the heart of the battle over how to run the nation's largest school system. With the law that gave control to the mayor set to expire at the end of June, the battle over school governance has now moved to Albany. After months of hearings and hundreds of pages of reports, the debate now moves into its final stages.

THE STAKES

The showdown over how New York should run its education system has elicited an almost unprecedented level of involvement, discussion and concern. Hearings and forums have been held throughout the five boroughs by politicians and advocacy groups. A range of organizations have issued their recommendations, many in the form of comprehensive reports. Lobbying has started in Albany with activists and city employees trying to shape the legislature's decision.

On the surface, the issues seem stark. The legislature must either renew the law or else stand by as the current legislation "sunsets" and the schools revert to the "old system," with a central Board of Education running the schools and appointing the chancellor.

In fact, the choices confronting the legislature stack up as far more nuanced. Although the system could go back to the era of 110 Livingston Street if the legislature does not act, no one expects that to happen because, whatever people think of the current system, virtually no one likes the old one.

Most -- though not all -- of the people weighing in on the issue support some form of mayoral control. So the issue becomes not whether one eliminates the current system but how much one changes it, if at all. The mayor and his staunchest supporters say not at all.

"Full control, matched with complete accountability -- must continue," said the Daily News, one of the mayor's most avid backers on this issue. "Calls to weaken a mayor's grip on the schools -- not just the hold of this mayor, but of any mayor -- must be rejected."

While an increasing number of American cities have moved toward some kind of mayoral control, New York and the District of Columbia offer the system in its most unadulterated form, with the fewest controls on the mayor and his appointed chancellor.

"No mayor has exercised such unlimited power over the public schools as Mr. Bloomberg," Diane Ravitch, a professor of education at NYU, former assistant secretary of education and frequent critic of Bloomberg, has written.

In the eyes of some critics, this is simply going too far. "We still think there are reasons to keep mayoral control," United Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten said in her introduction to the union's report on school governance. But she continued,"The experience of the last seven years points strongly to a need for a governance system that is more democratic, more accountable and more transparent."

In a similar vein, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer said, "I think you need a strong mayor to run the school system, but you do need parents to be able to go" somewhere to be heard.

Learn NY, a coalition seen as a mayoral ally, believes that progress in education is possible "only if the mayor has full authority over the program and budget," according to the group's executive director Peter Hatch. But it too sees "room for improvement."

Many community groups, parents, educators and others say they have been shut out of education in the city. The mayor, they charge, has erased the public from public education. Many of the plans proposed over the past months address this in some way. While some make major changes, others would render mayoral control virtually unrecognizable.

The Parent Commission on School Governance, for example, would make major substantive changes, removing the mayoral majority on the central board.

A report issued last week by State Senate Democrats seems to go even further, calling for sweeping changes including the creation of a new body that would serve as a "check on the chancellor." Among other things, it would "approve or disapprove all budgetary and policy decisions made by the chancellor," as well as union contracts. The Senate plan would also restore the power of the community school districts.

To some critics, such ideas keep mayoral control in name only. Reviewing some of the calls for change, a founder of Learn NY, Geoffrey Canada of the Harlem Childrens Zone wrote, "The key to the success of the new system has been holding officials truly accountable. ... New layers of bureaucracy will take us straight back to the bad old days, when corrupt and self-interested bodies answered to no one. We can't have it both ways: Either one person is in charge, or no one is."

So what do people want to change and how do they want to change it?

The Panel on Educational Policy

The law establishing mayoral control replaced the old Board of Education -- the body that appointed the chancellor and made key policy decisions -- with a new body that Bloomberg chose to call the Panel on Educational Policy. From the get-go, Bloomberg, who appoints a majority of the members, made it clear that this group would not have much autonomy.

When he appointed them, he declared, "I do not expect to see their names ever in the press answering a question either on the record or off the record.... I would not tolerate it for 30 seconds." The mayor removed any shred of doubt in 2004 when he arranged the sudden ouster of members who had questioned his plan to use test scores to determine whether children would be promoted.

Describing the panel's meetings, the New York Times recently reported, "The volunteer panelists ... rarely engage in discussions with those who rise to address them. They do not debate the educational issues of the day, but spend most sessions applauding packaged presentations by staff. Some have barely uttered a public word during their tenures."

Not surprisingly, most of the proposals modify the panel to some extent, since, given its current incarnation, it's difficult to figure out why is exists at all (and Washington, D.C. does not have any such board).

According to Steven Sanders, who helped write the mayoral control law as chair of the Assembly Education Committee and now represents the state School Board Association on the issue, the board was not intended as a rubber stamp. "Under the mayor's perspective, his appointees are people who receive their instructions in the morning and vote in the afternoon," Sanders said. But, he continued, "We did not create a board just for the sake of window dressing nor did we expect that the board would be treated by the mayor and the chancellor as just a messenger," he said.

Sanders said the association is looking at a variety of changes but that he would support keeping the mayoral majority on the board. "No one is suggesting he choose people who don't support his general views," he said.

Not everyone agrees. The United Federation of Teachers would end the mayoral majority -- a step that some see as attacking the essence of mayoral control. Instead the board would have 13 members serving a fixed three-year term with five named by the mayor, one by each of the five borough presidents, and one each by the public advocate, city comptroller and City Council speaker.

The Parents Commission on School Governance goes further, calling for a 15-member board, including six parent representatives. The mayor would get to name only three members. The Campaign for Better Schools, another coalition, explicitly calls for the mayor to have a minority on the panel, with the majority selected by "the City Council or other elected officials."

The Commission on School Governance, appointed by Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum, makes fairly minor changes to the panel, including providing its members with fixed terms (so they cannot be fired if they cross the mayor) and giving the group specific tasks, such as approving budgets, collective bargaining agreements with education department employees and contracts over a certain size. The principals union, while also expanding the panel's power, would add a member appointed by the City Council, which now has little role in the running of the schools.

State Assemblymember James Brennan of Brooklyn is drafting legislation modeled on the system used to select the Boston School Committee. It would establish a 13-member committee -- four of them appointed by the mayor -- that, in turn, would nominate two people each for for eight slots on the educational policy panel. The mayor would have to select appointees from those nominees.

According to Brennan, this preserves the mayor's majority on the panel while opening up the process. "I'm against a dictatorship of the mayor," he said.

Citing similarities between New York and Boston, he added that the Massachusetts city has shown it is "capable of doing as well or better than New York with a more consensus approach" to school governance.

City Comptroller William Thompson Jr. has put forth a similar proposal.

The Chancellor

Under the old system the board appointed the chancellor, who then found himself (they were all men) enmeshed in a power struggle between various factions of the board and the mayor. Chancellors fell victim to disputes over books about gay parents, condom distribution and budget cuts -- and left to seek their fortunes in cities from Miami to Los Angeles.

"The system was marked by complacency and a stream of chancellors who generally ended their short terms as political road kill," David Bloomfield, head of the master's program in education leadership at Brooklyn College, writes in his report on mayoral control.

Mayoral control gave the mayor the power to appoint the chancellor, just like he does at the Police Department, say, or the administrator of Children's Services. If nothing else, this has created stability. Joel Klein has served as chancellor since 2002.

Of course, not everyone sees that as a good thing. Klein had virtually no education experience before heading the city Department of Education. His approval rating has stayed far below that of the mayor, and many see his personality and approach as a major point of contention in Albany. Some have even theorized Klein might find himself sacrificed to save the mayor's robust model of mayoral control.

Most, though not all, proposals, however, continue to give the mayor the power to appoint the chancellor. The parents commission gives the final say to the mayor who would have to select the chancellor from among three candidates named by the reempowered Board of Education.

The principals union, like many of the other groups weighing in, would leave the power with the educational policy panel, but would appoint the chancellor for a four-year term subject to renewal and would only allow educators to hold the post, ruling out Klein.

The teachers union introduces an interesting twist, saying parents and teachers should get to evaluate the chancellor just as Klein and his evaluation teams now assess everyone else.

Power in the Districts

The previous bold experiment in New York City public education came when the city decentralized its schools, largely in response to complaints from black and Hispanic parents who saw the huge centralized system as ignoring the needs of their children. The city was divided into 31 community school districts -- and one for special education -- run by elected boards. Over the years, the boards saw their power eroded, due largely to charges of corruption, mismanagement and apathy in some districts.

The scaled down boards of 2001 had some power, however. They had some budgetary authority, zoned schools within districts and gave parents a place to seek redress.

Mayoral control was intended to preserve some of this authority -- over zoning and siting, for example. Here too, Sanders said, the administration has not complied with the intent of the law. Instead it "sought almost from day one to obliterate the community school districts," he said.

The districts play an essential role, Sanders said. "You need a digestibly sized education district, so parents don't get lost in the system," he said.

The administration first shifted some of the power to 10 "regions" and then, in a midcourse adjustment, placed more power with individual schools.

In response to suits, the city has had to preserve the school districts, but they exist as a shadow of their former selves. Faced with such limited authority, many parents see little point in running for the Community Education Councils, which have replaced the community schools boards.

With charter schools fighting public schools for scarce space, decisions over where to place schools have grown increasingly rancorous. Stripping the local districts of control over this has enraged many parents. Plunging into that issue, the principals union would require the councils approve any charter schools in their districts as well as any school closing, though that could be reversed by the educational policy panel. The teachers union would allow the local councils to set boundaries for schools and to hold hearings over school closings and openings, including charters, but would not give it the power to approve or disapprove such plans.

This is one area that Learn NY sees as needing change. "We think there is room [for giving] parents and communities more input and assistance navigating the system," Hatch said.

To bolster the councils, Stringer has proposed modeling them on the city's community boards. The councils now face an inherent conflict, he said, in that they are run by the agency whose actions they are supposed to monitor. Instead his Unified Parent Engagement Process would switch authority over the councils to the borough presidents. Although they would remain advisory, this would give them some heft. "Community Boards are advisory but by any measure... you have the city worrying about what the community boards think," he said.

Thompson would have the presidents of school parent associations in each district select the members of the councils from among themselves.

As the community school districts have lost power, so have the district superintendents. "A key problem is that district superintendents are not functioning as the critical link between parents and the central administration, leaving parents with no place to turn," Thompson said in recent testimony.

The principals union would provide the superintendents with sufficient staff to provide information to parents and involve parents in the schools. The parents commission would restore the power of the community school district offices. It would also bring high schools -- now administered citywide since Klein essentially eliminated neighborhood high schools -- back to the community level "to provide opportunities for high school parents to provide input to the policies and planning that affect their students."

In the Schools

When Bloomberg and Klein redid their reorganization they gave principals increased power to determine budgets and programs. The city would hold the principals accountable for the success or failure of their schools, the reasoning went, and in return they would have the authority to make decisions affecting their schools.

At the same time, though, some parents have felt cut out of the authority even at the most local of levels. For example, the administration has taken power away from School Leadership Teams, committees with representatives of the school administration, faculty, parents and students. A number of proposals -- including Gotbaum's, the parents commission and the United Federations of Teachers'-- would restore some of their authority. The teachers union would also give parents and teachers more power over the selection of principals and assistant principals, another local authority that Klein has largely curtailed.

Checks and Balance

While Bloomberg tries to present the Department of Education as just another city agency -- albeit by far the richest -- the department, like other New York school systems, is technically a state agency. Bloomberg has been quick to use this dual status to avoid subjecting the department to the scrutiny. This comes up in two key areas: measures of student achievement, such as test scores, graduation rates and students' ability to do advanced work, and department procurement and contracts.

The administration relies heavily on test scores when it cites the achievements of mayoral control. Others question the validity of the tests and the interpretation. Ravitch, for example, largely dismisses the results on the state tests, preferring to look at the federal National Assessment of Education Progress. On that, she has written, "New York City showed almost no academic improvement between 2003, when the mayor’s reforms were introduced, and 2007."

Similar debates surround high school graduation rates. In addition, critics charge the administration has forged ahead with a number of bold initiatives without any solid evidence that they work. This has been the case with small high schools, changes in promotion polices, adjustments to the curriculum and other key programs.

To remedy this, a number of the plans call for increased monitoring. The Gotbaum commission, the City Council Working Group and the Campaign for Better Schools see that task as going to the Independent Budget Office. Thompson calls for the creation of a new office.

The administration's refusal to subject all department contracts to review by the comptroller has raised hackles at City Council. At a recent hearing, department officials said the department's unique structure -- literally hundreds of schools all buying goods and serves -- required it be treated differently than, say, the parks department.

Critics, including Thompson, charge that, free of scrutiny, the department has entered into a large number of no-bid contracts, including a deal with management consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal that the department claims saved the city millions of dollars. Most parents, though, remember it as laying the groundwork for the decisions that resulted in thousands of city school children being stranded at school bus stops in the dead of winter.

In a recent report, Thompson also highlighted rampant cost overruns at the department, figures that the education department promptly disputed.

A variety of the proposals would subject department procurement to greater scrutiny. Thompson and the City Council Working Group would simply treat the education department as another city agency.

Other proposals offer additional mechanisms to watch over the department. The parents commission calls for a new "independent citywide parent association" so parents will develop the skills to be active members of the school leadership teams and play a major role in the selection of heir school administrators. Similarly, the Campaign for Better Schools calls for an "independent publicly funded Center for Parent and Student Service and empowerment... to outreach, train and support parents and students."

The parents commission also devotes a significant portion of its report to improving special education in the city, including having a designated seat for the parent of a special education student on the educational policy panel and expanding the citywide Council on Special Education.

ON TO ALBANY

By any measure, the competing concerns and proposals leave the state legislature with a lot to unravel. Lobbying has begun in earnest. Last Tuesday, for instance, many saw a number of people, including Klein, Gotbaum and members of Gotbaum's commission pressing their cases.

In the Assembly, several bills have been drafted or are about to be addressing specific aspects of the issues. Jeffrey Dinowitz, for example, is putting forth Stringer's community education board plan, while Brennan will draft a bill restructuring the educational policy panel. While Sen. Daniel Squadron is sponsoring Stringer's proposal in the Senate, there seems to be fewer bills in that chamber, at least for now. So far, observers say the education committee, chaired by Suzi Oppenheimer of Westchester, and concerned senators from the city, are trying to come up with a consensus proposal.

This being Albany, one would expect much to be settled behind closed doors -- like what recently happened with the budget. So far the two leaders -- Malcolm Smith in the Senate and Sheldon Silver in the Assembly, both of New York City -- have not publicly responded to the various ideas.

The current law ends on June 30, with the legislature set to adjourn about a week before that. Some think that Silver would prefer this not be the last thing on the legislature's agenda before summer vacation. By any measure, though, time is short.

Sanders does not think the legislature will try to "re-create the wheel" but instead "will try to improve upon the law written in 2002 and 2003." He says four things could happen:

--The law would not be renewed, unlikely because virtually no one wants this to happen;

--An extension of the current law as is. Sanders also sees this as unlikely;

--Extension of the law for a year, leaving the legislature to confront this all again in 2010. While some legislators might like this -- for one it takes the debate out of a mayoral election law -- do they really want to be tangled in this in a year when all of them, along with the governor, face the voters?

--Significant changes occur.

Over the next two months, "Hopefully the majority party in the Assembly will forge a consensus and try to work with the governor, the Senate and all the stakeholders," Brennan said.

The seemingly endless controversy over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority could give one pause. But Brennan sees this as quite different. "The is about policy inside New York City," he said, and does not involve taxation or "divisive regional issues."

BEYOND GOVERNANCE

The popular wisdom in education these days -- from the Obama administration on down -- holds that, while mayoral control does not guarantee improvement, it is at least a prerequisite for it.

"A lot of the gain we have seen... can be attributed to having one person in charge," said Hatch of Learn NY.

But some question whether it really makes a difference. The parents commission sounds a skeptical note. "In the past 40 years, the structure of the school system has ranged among varying form of centralization and decentralization, with chancellors who were educators and those that were not," its report says. "Yet by every measure ... little has changed for the majority of students who are primarily low-income children of color."