The South Bronx feeds the region. Eighty percent of the metropolitan area’s fresh produce and 40 percent of its fresh meat comes through the huge Hunts Point market there. And with the opening of the new Fulton Fish market at Hunts Points last week, the neighborhood will be a leading supplier of fish as well.

| Related Stories in the Community Gazettes: • Growing Food in East New York • Marketing Health in the South Bronx • Small Grocers Survive on the Upper West Side |

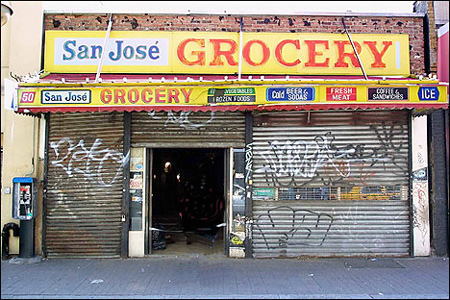

But little of that fresh food reaches people in the immediate vicinity. Hunts Point is a wholesale market, off limits to individual consumers. The neighborhood has only one grocery store of any size – making it among the most poorly served communities in the city -- and less than a quarter of its bodegas carry fresh vegetables. (See related story.)

The South Bronx presents perhaps the most glaring example of New York’s food paradox: While the city offers an amazing cornucopia of food – gourmet treats, heirloom produce, food prepared to every religious specification and ethnic taste – some poor neighborhoods lack even a simple medium-sized grocery store. This forces residents to contend with high prices and the unhealthy food. That, in turn, contributes to soaring rates of diabetes and obesity.

FOOD CITY

Food is a multibillion-dollar business in New York City with more than 1,100 grocery stores of at least 4,000 square feet. New York boasts the fresh fish markets and vegetable stands of Chinatown, the Middle Eastern grocers of Atlantic Avenue and icons like Zabar’s. Markets such as Dean and De Luca and Citarella cater to the food obsessed planning to serve Belon oysters, foie gras and truffles on their Thanksgiving tables.

Despite all of that and tens of thousands of smaller delis, greenmarkets and bodegas, many New Yorkers confront what the American Institute of Nutrition has called “food insecurity” – an inability, either because of money or availability, to get safe, nutritional food.“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format) a 2004 survey by City Limits, looked at the number of grocery stores in each ZIP code. If it's not surprising that affluent Soho has the most places to buy food per resident, it is certainly startling to discover that several ZIP codes in Queens, including ones covering parts of College Point and Bayside, have no grocery stores at all. Overall, Manhattan has the most grocery stores per resident; Brooklyn the least.

Despite all of that and tens of thousands of smaller delis, greenmarkets and bodegas, many New Yorkers confront what the American Institute of Nutrition has called “food insecurity” – an inability, either because of money or availability, to get safe, nutritional food.“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format) a 2004 survey by City Limits, looked at the number of grocery stores in each ZIP code. If it's not surprising that affluent Soho has the most places to buy food per resident, it is certainly startling to discover that several ZIP codes in Queens, including ones covering parts of College Point and Bayside, have no grocery stores at all. Overall, Manhattan has the most grocery stores per resident; Brooklyn the least.

“It’s tough to get high quality supermarkets into the â€hood,” Alicia Glenn, vice president of Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, has said. Supermarkets must sell a large volume of goods and so need large amounts of space – perhaps a half a city block.

And some in the food industry predict the grocery shortage could spread to more affluent areas as New York becomes an ever more expensive place to do business. “The better the neighborhood, the less supermarkets there are going to be” because rents are too high, said Morton Sloan, part owner of 10 Associated supermarkets in Manhattan and the Bronx.

Overall, said John Catsimatidis, the owner of Gristedes, the picture is “bleak” for grocery stores throughout the city, largely because of high rents. No one – from Whole Foods to the small mom and pop – is immune to the industry woes, he said, adding, “Something’s got to give.”

LIFE WITHOUT GROCERIES

“When I moved back to Central Brooklyn in 1985, I was struck by its barren nutritional landscape …. The storefront food provision systems themselves – â€bullet-proof’ fast food joints, poorly stocked and over-crowded supermarkets, cruddy, stomach-curdling bodegas – seemed to represent a level of self-destruction and dietary corruption that went well beyond my inability to buy tofu,” writes Mark Winston-Griffith. “Seldom do we consider one of the most basic elements – how an area feeds itself – as a sign of neighborhood well being.”

And many areas feed themselves expensively and unhealthily. In one study (in .pdf format) researchers found that a mango cost 67 cents at Pathmark, 79 cents at Associated -- and $1.79 at an East Harlem bodega.

The high prices are a real obstacle for many poor New Yorkers. Some 2 million people in the city are at risk of going hungry. As many as one in five –- and a quarter of the city’s children –- need help from food pantries and kitchens. This is double the national rate, according to a report by Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum.

But at least the East Harlem bodega had a mango. Many similar stores carry little fresh produce and no fresh meat or fish. In 2004, researchers compared the availability of several foods healthy for diabetics in East Harlem and Upper East Side grocery stores. Only 18 percent of the East Harlem stores had all five of the recommended foods, compared with 58 percent of the Upper East Side stores. And in East Harlem, stores selling unhealthy foods near schools outnumbered those selling healthy foods by almost six to one, according to one study.

HEALTH EFFECTS

All of this takes a toll on health. According to a 2003 study by the city health department, about 8 percent of all adult New Yorkers have been diagnosed with diabetes. With about a third of all diabetics unaware that they have the disease, as many as 12 percent of New York City adults could have diabetes – well about the national rate of 7 percent nationally.

In addition, an increasing number of New York City children are developing what used to be called adult-onset diabetes but is now referred to as Type II diabetes – because so many children now develop it. Doctors blame obesity, poor foods and lack of exercise. “Simple sugars, refined sweets, corn syrups, sodas, vegetables like potatoes and corn, without question, create an unfavorable environment for the pancreas," Dr. Henry Anhalt, director of pediatric endocrinology at Maimonides Medical Center, told the Daily News. He added that meals high in fat and calories, such as a typical fast food lunch, increase the risk.

Almost a quarter of all New York City elementary school students are obese, compared with a national rate of 15 percent. The problem is particularly severe among Hispanic children, more than 30 percent of who are obese.

ATTRACTING SUPERMARKETS

The problem has its roots in the 1950s and 1960s, when many grocery stores followed their middle-class customers to the suburbs. As a result, many who remained in the city had to rely “on small independent groceries that charged high prices and offered minimal variety and corner stores selling a limited selection of processed foods,” according to “Healthy Food, Healthy Communities,” a report by PolicyLink.

Although new stores have entered the city, the problem persists, despite tens of thousands of consumers eager for better food. “It’s not that they don’t want healthy foods or know the value of health foods,” said Kimberly Moreland of Mount Sinai Medical School.

In fact, many people go to great lengths to travel to good grocery stories. “People find a way to get to the supermarket,” said Rebecca Flournoy, a senior associate at Policy Link. “But if you’re going to have to take public transit and you’re on the bus for an hour and a half, and you have two kids with you and six bags of groceries, you’re not going to do it that often.” That makes buying perishable items particularly difficult.

Faced with this shortage, community and health activists, sometimes working with farmers or grocers, have tried to bring healthy food into communities. In some cases, the solution is a supermarket. For example, the Abyssinian Development Corporation and the Retail Initiative joined with Pathmark for a store in Harlem. The project stalled – due largely to opposition from small local grocers – but eventually opened in 1999. Such stores provide many benefits to the community, said Flournoy, including jobs and spurring economic development.

And the stores make money. “We’re pleased with the performance of our urban stores,” Harvey Gutman of Pathmark told Supermarket News. “The fact that we continue to open stores is evidence that we consider them to be successful.”

But, he said opening such stores in the city poses special challenges. “Land is scarce and expensive. Often it needs to be rezoned,” he said. “Opening a store in an urban community involves the participation and involvement of many political and economic entities.”

Rent provides a major barrier. To address that, some have proposed tax breaks for grocers, particularly smaller ones. (See related story.) Sloan of Associated would like the city to provide rent subsidies as well.

PROVIDING HEALTHY FOOD

|

But not every block can support a supermarket or even a medium sized grocery store. And so activists are looking to other ways to improve neighborhood food offerings.

In the Bronx, one effort aims to encourage bodega owners to provide healthier food. And farmers markets and farm stands have become increasingly prominent in the city. The leading effort is the 54 markets run by the Greenmarket project of the Council for the Environment of New York. These greenmarkets feature farmers from upstate, Long Island and New Jersey who come into the city once a week or more to sell produce and farm related products, such as jam and bread. Just Food, a non-profit organization, has sponsored 33 community supported agriculture – or CSAs – in the city. In these buying clubs, residents of an area agree to purchase food on a regular basis from a small farmer. The customers get a guaranteed source of fresh food; farmers get a guaranteed source of income.

Just Food also runs the City Farms project, which works with gardens in the city to distribute what they grow to the community. In 2004, some gardens in the city produced more than 30,000 pounds of food.

Some gardeners sell their wares in farm markets, such as East New York Farms! (see related story) and at so-called urban farm stands. The gardens also donate to soup kitchens and food pantries. “Community gardeners know who needs the food,” said Rebecca Ferguson of Green Guerillas.

The city’s economic health can hamper such efforts. In more depressed cities, says Kathleen McTigue of Just Food, it’s easier to find land to cultivate. Here, she said, “you have to make the most out of small growing spaces.”

But, said Ferguson, the potential in New York remains “massively untapped.” Land awaiting development can be farmed she said, and vegetables can be grown on rooftops and in window boxes.

Some of the available land is returning to an old use. For eight generations, beginning in the 1650s, Wyckoffs lived and farmed in East Flatbush, helping to make Brooklyn and Queens centers of agriculture as late as the 1880s. While Brooklyn will probably never return to its agricultural heyday, area residents are once again farming the grounds of the Pieter Claesen Wyckoff House. And on Sundays in the summer and fall, a farm stand – the kind of thing one expects to see on a back road upstate – sells home grown goods, in the middle of the drab urban landscape – and in front of Brooklyn’s oldest house.

For More Information:

Food Bank for New York City

Green Guerillas

Greenmarket, Council on the Environment of NYC

Hunger Action New York State

Just Food

Northeast Regional Anti-Hunger Network

Articles and Studies

“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format)

Food Redlining: A Hidden Cause of Hunger

Harvest in the City (Earth Island Journal)

Healthy Foods, Healthy Communities

The Hoax of the Food Desert (Ludwig von Mises Institute)

Hunger and Obesity in East Harlem (in .pdf format) New York City Coalition Against Hunger

It’s Just Food (NYU School of Journalism)

Splat (New York) The war between Fresh Direct, Fairway and Whole Food

Â