If a revitalized waterfront is part of the vision of the current mayoral administration, with projects planned throughout the city, progress has been spotty, beset by squabbles, cost over-runs, reversals or simply inaction. .

Minerva's View

The tale is that the statue of Minerva in Green-Wood Cemetery waves at the State of Liberty in New York Harbor. The nine-foot goddess of wisdom has been sending that greeting since 1920. That's when her bronze form was put up at this highest point in Brooklyn to commemorate a Revolutionary War battle.

When a developer tried to put up a condominium tower at 614 7th Avenue at 23rd Street in Brooklyn that would block the view between the two statues, people in the South Slope neighborhood protested.

At 70 feet, the tower would be taller than the 40 feet the new zoning allowed. But the developer Chaim Mussencweig argued that he had laid the foundation for the building before new zoning went into effect. The tower should be grandfathered in on the old zoning rules.

On September 12, the city Department of Buildings denied his appeal. The building will have to abide by the new zoning rules, and Minerva can keep waving at her big green buddy in the harbor.

It wasn't just for sentiment's sake that neighbors argued to limit the tower. They wanted to maintain a neighborhood of modest-sized residences. Minerva's shield helped win that battle, and now residents have new zoning laws that will keep them safe from marauding high rises.

Belt Parkway Path

After bumping through Brooklyn streets past the hurly burly of apartments and businesses, the Belt Parkway always provides a welcome view of open water and the lofty Verrazano Bridge in the distance. A 13-mile path along the shore to the bridge gives residents of Bay Ridge a place to walk and bike. It was the location for a love scene in an iconic Brooklyn movie, Saturday Night Fever. But like the film, the path shows its age.

The seawall deteriorated badly over the six decades since it was built on landfill, and last summer, the Parks Department closed a two mile stretch of the walkway in order to rebuild it. Cost was estimated at up to $14 million, to be completed by this summer. Complications of backed-up sewers that caused soil erosion delayed the project, now costing more than $20 million and scheduled to be done this month..

Political complications also ensued. Republican Congressman Vito Fossella took credit for getting the project going and for getting $5 million in federal funds.

In a speech in August, his Democratic opponent Steve Harrison said that Fossella waited years too long to spur the repairs, and that he never actually received the federal money. All of the funding came from the parks department.

The issue is likely to remain a factor in the campaign. It'll be worth watching to see each of these candidates for Congress try to prove how much more he cares about a waterfront park than his opponent. Since the city parks department is in charge of the Belt Parkway paths, a Congressional representative won't have much control over the project. But if park advocacy becomes a viable campaign issue, it might be a charming election season in Bay Ridge.

Ikea and the Graving Dock

This isn't a case of paving over paradise and putting in a parking lot, as the lyrics go. It's the case of paving over a gritty piece of Brooklyn's waterfront industry to put up a parking lot.

To some, that might not sound like a bad thing, replacing a noisy, dirty industrial site in Red Hook with a big store that sells good-looking furniture at good prices.

But to some people who work in the waterfront's oldest profession – shipping -- the loss of a graving dock to repair ships is a truly bad idea.

Built in 1867, the dock is a clever structure. A ship floats into the watery parking spot, a door slides shut behind it, and pumps drain the water so that the ship can be repaired. At more than 700 feet, the dry dock can accommodate large ships. Replacing it would cost a fortune.

There's only one other graving dock in the harbor, and it's in New Jersey. Ships go to other ports for maintenance and only use one here for emergency repairs. As more and more ships come into New York Harbor every year, it's shortsighted to fill in a usable graving dock, argues Captain Andy McGovern of the Sandy Hook Pilots Association.

At this point, good arguments for the graving dock's preservation aren't likely to make a difference. The city changed the zoning from manufacturing, and the operator sold the property in early 2005.

Though Ikea is unlikely to take them up on their ideas, the Municipal Art Society offers a plan for accommodating Ikea and their parking needs and preserving the dry dock.

At present, Ikea may leave the outline of the graving dock as a historical relic. Industrial archaeologist Mary Habstritt says that would be like "the outline of a body after a homicide."

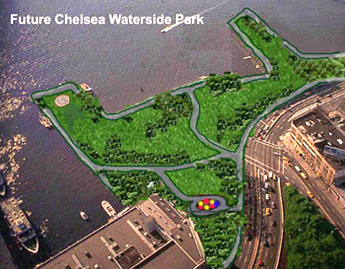

Hudson River Park

Hudson River Park from the Battery to 59th Street features smooth, well-marked walking and bike paths. It's a spine that is being filled out and dressed up with grass, trees, playgrounds, piers with vistas, boathouses, and sports venues. But the park is a work in progress, and the path to completion is not perfectly smooth.

The Hudson River Park Act of 1998 allocated state and city funding ($360 million so far) to remake the five-mile-long park from a stretch of derelict piers into a waterfront showplace. By rebuilding 13 piers, the plan respects the historic importance of the working waterfront.

Today, the completed sections show off lush lawns, pleasant playgrounds, and spacious piers.

The section adjacent to Greenwich Village opened in 2003. Clinton Cove Park at 54th Street opened last spring. A newly landscaped park and walkway opened in July from Battery Place (the west end of Battery Park) to Chambers Street. In mid-October, Pier 84 at 42nd Street (next to The Intrepid, the museum battleship) will open, becoming the largest public pier in Manhattan. It will feature a boathouse and a large fountain.

Work recently started on sections across from Tribeca and Chelsea. Two new piers will offer spectacular views. These are not quick projects. They should be ready by 2009.

There are growing pains. Pier 63 in Chelsea will be demolished and rebuilt as a public space. In order to start the work, The Hudson River Trust, which runs the park, evicted the commercial enterprises there.

Basketball City, which occupied Pier 63 for nine years, fought eviction. Legal appeals gave them several reprieves over the years. But they lost their last appeal in August and had to vacate the pier by September 10.

Sixteen high schools from around the city and corporate leagues rented space in the six courts of the for-profit courts. Now Basketball City is scrambling for temporary space.

Another venture at Pier 63 knew that demolition was coming, but was still unprepared. When the Manhattan Kayak Company www.manhattankayak.com had to vacate the pier on September 10, it seemed to cut the boating season cruelly short. They had counted on Basketball City prevailing again, and they thought that the trust wouldn't throw them out so quickly.

The kayak company co-owner was philosophical about it: "The suddenness of this came as a bit of shock to us all as you may imagine, but we must adapt and continue as we always do," wrote Eric Stiller on the company's Web site.

In the meantime, the kayak company will work from the boathouse at Pier 96 (at 57th Street). Next year, the company will run their operation from 26th Street.

The pier also houses the New York Police Department's mounted unit, which will move its stables to another pier.

Lower East Side

Basketball City eventually plans to move to a pier on the East River just north of the Manhattan Bridge, one of three piers on the Lower East that are scheduled to be refurbished and opened to the public. The piers are currently behind tall chain-link fences.

Re-using the piers for new purposes is part of a larger plan to fix up the walkway/bikeway under the FDR drive adjacent to the Financial District, Chinatown and the Lower East Side. There is a biking and walking path under the FDR with glorious views of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, but beneath the highway next to the promenade along the river are parking lots, bad lighting and noise.

Funding for beautification is already there, in part from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (from federal funding allocated in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center). The work has yet to begin, however.

City Councilmember Alan Gerson, who represents the area, says he's looking for an expedited timetable for the entire waterfront project along the East River. "We should be making better progress," he says. "We should not be going through 'hurry up and wait.'"

East River Park

Just north of the Manhattan Bridge, the park is still a mess, though rebuilding started on the walkway along the river last year. After contractors tore out the old promenade, soil from the muddy embankment began sliding into the river. The contractors placed bales of straw to stop the churned up mud from further erosion.

The work then stopped. Most of this summer, the construction site looked deserted, with heavy machinery sitting idle. Now, a parks department spokesman promises it will resume.

The delay did not attract much complaint from the neighborhood. The walkway has been closed since 2001, when it was deemed unsafe, so the community is used to living without it.

Carter Craft of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance thinks the lack of community outrage at the stalled rebuilding has to do with how cut off the neighborhood is from the river on the Lower East Side. "They're so used to having crappy access," he says. He notes that there are just three pedestrian bridges across the FDR Drive to the park.

If construction stopped on the West side, where access is plentiful, says Craft, "they'd go nuts.”

Some on the Lower East Side explain the reaction differently. "The kind of development that happened on the West Side is the kind of development that’s going to raise rents and the cost of living, and I think there’s a huge part of this neighborhood that’s very scared of that," said David McWater, chair of Community Board 3 in Grand Street News, a neighborhood magazine. "They’d rather leave it alone because we don’t want everybody wanting to move here, because then I’m going to have to move to Iowa."

A Faster Track

The delay in the promenade construction led at least to one unexpected benefit. Since the landscapers couldn't work on the promenade, they transferred their energies to a runners’ track in the park at 6th Street. Runners will have their place to train in service at the end of September, well ahead of schedule.

Â