City Council Acts to Slow Transportation Projects

The City Council yesterday flashed an orange light at a city Department of Transportation that some members see as ignoring warning signs in its push to make city streets more hospitable to pedestrian and bicyclists.

By unanimous votes, the council approved two measures, sponsored by transportation committee chair James Vacca, on projects that reconfigure city streets One measure looks forward, the other back, but both reflect the feeling among some council members and residents that the transportation department under commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan has become an agency with a mission that forges ahead with its plans for plazas and bike lanes without benefit of consultation or facts.

In Vacca's view, these bills would change that. "The days when the Department of Transportation could unilaterally reconfigure our streetscapes are gone," he said.

The first bill -- Intro 626A -- would require the transportation department to consult with other city agencies, including Small Business Services and the police and fire departments, before it reconfigures streets. It also would have to report to the City Council and relevant community board on the results of those talks.

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Vacca said the measure was prompted in part by complaints from small businesses.

"Many of the bike paths, many of the pedestrian plazas negatively impact small businesses and their ability to survive in the City of New York," Vacca said.

In addition, people with disabilities -- particularly the visually impaired -- have told council members that "pedestrian plazas have not been constructed in a way so that it is safe for them to move through the plaza," Quinn said.

The second measure – Intro 671 -- requires the transportation department to provide statistics on the effects of the street change within 18 months of when the reconfiguration went into effect. This would include data on traffic flows, accidents and emergency vehicle response times. Quinn said was in part a response to complaints from residents of the Borough Park section of Brooklyn that the establishment of a pedestrian plaza there had slowed response time for emergency vehicles.

The administration has come under fire for its use of data to justify its ambitious street changes. When it announced the establishment of a pedestrian mall around Times Square, the said its would improve traffic flow. While the mall has done many things, it has not, by the city's own account, reduced gridlock or increased traffic speeds. The city first tried to keep that data private and then, when it finally was released, sought to dismiss the importance of its numbers.

Putting on the Brake

Yesterday's votes are the latest in a series of attempts by council members to slow down the transportation department's plans. Earlier this month, the council unanimously passed a bill requiring that the department give community boards advance warning of any planned bike lanes in their area and that the department participate in any hearing on the proposal the community board might wish to hold. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has signed the bill.

In February, council members approved a measure, later signed by the mayor, requiring the city to report on pedestrian and bicycle accidents – including those in which a cyclist struck someone on foot -- as well as automobile related accidents. Those backing the bill, including the widow of a 50-year-old man killed when he was hit by a bike said more accurate figures could help the city craft a better policy on bike lanes.

As the administration has stepped up its effort for pedestrian plazas and especially bike lanes – it has added some 250 miles of the lanes in the last four years -- opposition has increased as well.

Along with taking issue with the street enhancement themselves, opponents have criticized the administration for not adequately consulting with people in neighborhoods about where the bike lanes and plazas should go -– or it they should be there at all.

"Bike lanes drop out of the sky without any notice to the community," Council member Lew Fidler, the sponsor of the bill requiring consultation with community boards, said last year.

While supporters of the recent council bills -- including Fidler -- deny they are anti-bike lane, some doubt it. Bicycle advocates said the measures would subject the lanes to a level of scrutiny not seen on many other projects. "No other safe-street improvement seems to get that kind of treatment," Michael Murphy of Transportation Alternatives told Capital.

As the debate has grown increasingly acrimonious, bike and pedestrian advocates say city residents want to slow traffic and make street safer for those who walk or bike. They cite a poll released in October, which found that 58 percent of New Yorkers support the bike lane program.

"Most New Yorkers like bike lanes," Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, has said. "I don't know anyone who s pro-crash or wants to see more injuries and deaths on our roads. Streets with bike lanes in New York City are 40 percent safer than those without."

Murphy expressed concern to a reporter that bills such as those passed yesterday might slow down the installation of new bike lanes. Of course, some council members might say, that's the idea.

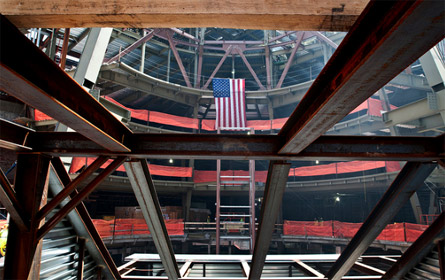

After Delays, Fulton Street Transit Hub Takes Shape

After years of political wrangling and delays, components of the Fulton Street Transit Center are finally coming together.

Yesterday, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority reopened the southbound platform of the Cortland Street station, which has been closed since 2005. Recently the authority celebrated the openingof a new entrance at 135 Williams St., which offers improved access to the A, C, 2 and 3 platforms. The entrance is decorated with a refurbished mural from a now defunct midtown hotel, and is one of three entrances that will offer similar improvements.

"We have reached yet another significant milestone as we move forward to complete what will become a landmark transportation facility," MTA Chairman and CEO Jay Walder said at the event. "Once complete, this complex will provide our customers with a more seamless experience at this major downtown hub."

The openings come as the above-ground dome begins to take shape, as does the Dey Street Passageway, which will connect the Fulton Street Transit Center with R train service and the World Trade Center Transit Hub, which provides PATH train service to New Jersey.

By the time the complex is complete, it will link 12 subway lines and is expected to serve 300,000 riders a day.

Years in the Making

The original concept for the project dates back to the 1990s. The transit center idea came out of the Lower Manhattan Access study, which aimed to improve transportation in Lower Manhattan, according to Bill Wheeler, director of MTA planning. One of the main report's proposals called for reconstruction of the Fulton Street Complex to make it easier for passengers to transfer between various trains and navigate the complex. The project, though, gained momentum after the 9/11 attacks as part of the general push to rebuild and improve lower Manhattan.

"Anyone who knows the transit system as they do knows that the complex is a mess and is a real pain for anyone who tries to negotiate from one line to another, especially if you're unfamiliar with it," said Jeffery Zupan, senior fellow for transportation at the Regional Plan Association. "It occurred to the MTA that they could put some money into this to help make the complex better and help Lower Manhattan. It didn't come out of nowhere, but it wasn't on top of the list."

Once completed, the transit center will connect the Fulton Street complex, with its 2, 3 ,4 and 5 train services- to the Cortland Street station that serves the R, the Broadway-Nassau Station with the A and C trains, and the Chambers Street-World Trade Center station, which serves the E and PATH trains. The station will also feature a glass station house with 23,000 square feet of retail space at Fulton Street and Broadway.

The centerpiece of the complex will be a large egg-shaped structure on top of the glass station house – usually referred to as the oculus -- that will act as a sunroof and reflect sunlight down to platform level.

The Right Answer?

While the existing subways stations needed work, Nicole Gelinas, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, contends that the Fulton Street Transit Center designed after 9/11 will not address the transportation problems in the area, namely the lack of direct connections to residential areas outside of the city. In her view, the entire project was the result of a rush to rebuild the downtown area after the 9/11 attacks.

"There was kind of this big focus that we have to rush to concentrate on the World Trade Center site, and maybe they should have done more to help the region," said Gelinas. "It may have been better for them to spend on actual rail connections."

According to Gelinas, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played a big role into making the Fulton Street Transit Center a reality, the transit center being in his district. The speaker's office declined to respond.

"A lot of the rebuilding has been driven by local politics. Sheldon Silver really pushed this as one of the projects he's really been instrumental for," said Gelinas. "He made it clear in the months after 9/11 he wanted this transit center in lower Manhattan and to get funding for other projects, they [the MTA] supported this."

Designs and Delays

Groundbreaking on the transit center took place in June 2005, with completion originally slated for 2007. Cost overruns, though, started to become a problem in 2006, mainly due to the expense of relocating businesses on the site and acquiring property. In 2008, the MTA indicated that it might have to abandon the dome structure, which was the centerpiece of the project, and that there might not be any visible above ground structure. By this time, the project was slated to be done in 2010, and was $111 million over its original $799 million budget.

After reviewing and revising plans in, the MTA announced in 2009 the new completion date as June 2014, and the revised cost as $1.4 billion. Despite the federal government's refusal to pay for any cost overruns, the MTA received $423 million in stimulus funds to help continue the construction of the project. To keep costs from rising further, it was decided to narrow the Dey Street Passage from 40 feet to 29 feet. After going back and forth on the design of the Fulton Street station, the MTA is constructing the dome as originally planned, but with additional 23,000 square feet of retail space; to increase potential revenue for the project.

Some delays were attributed to engineering challenges in the area, including the reconstruction of the nearby Corbin Building, which will be 124 years old when construction is complete. Meanwhile the World Trade Center transportation center has also had its share of problems. The cost for the building – with its birdlike design by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava – could reach $3.8 billion and may not open until 2015.

According to the MTA, the Fulton Street project will cost roughly $1.4 billion, with 97 percent of that covered by federal funds. And now, according to Donovan, the transit center is being opened in sequence, with expected completion in June of 2014.

Zupan cites the complexity of the Fulton Street project as a key factor in the delays there, but he said the woes will be a distant memory once the general public sees the completed center.

"It's clear they've had problems moving forward, they had to redesign it to reduce cost. With many of these infrastructure projects they're very complex ... and it's very difficult to assess these things in advance," said Zupan. "When the project is done, it's going to last for 100 years, and it'll long be forgotten that the project is over budget and it took as long as it took."

Council Approves Fines for Taxi Refusal

The City Council wants to slam the brakes on the taxi industry's bad apples.

To ensure taxi drivers do not discriminate against passengers' destination -- or race -- the council approved legislation Wednesday that would drastically increase fines for drivers who refuse certain passengers. The bill, which was approved unanimously, is part of a larger effort by the Bloomberg administration to ensure residents of the outer boroughs receive taxi service like those in Manhattan.

"You wait around, your arm out and a taxi finally drives up," Council Speaker Christine Quinn said. "You try to get in the car, and the driver won't let you. You say, 'Queens,' and the next thing you know the cabbie just drives off."

The council's proposal, Quinn said, would deter this practice.

The city's taxi drivers, however, criticized the measure, arguing it exaggerates the prevalence of driver refusal and distracts from the real issue discouraging drivers from outer borough trips: the economy.

"They seem more interested in punishing drivers than actually addressing the issue," said Bhairavi Desai, the executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, which represents yellow cab drivers.

The proposal is the latest battle between the City Council, the Bloomberg administration and the taxi industry within the last month -- disputes that have gone from fare hikes to a new class of cab.

No Right to Refuse

The legislation, which the mayor is expected to sign, would also affect drivers who overcharge passengers and who illegally ask riders where they are going before entering the vehicle. Asking the destination before entry, said council officials, is often seen as a way to avoid outer borough rides.

Under the legislation, a first offense would increase from $350 to $500. If a driver receives a second offense within 24 months, the maximum fine would double -- from $500 to $1,000. If a driver receives a third violation in a 36-month period, he or she could lose their license.

According to the City Council, the 311 system receives about 300 overcharging complaints a year. For refusals, council officials said 311 receives between 200 and 300 complaints a month.

Desai said the refusal figures are exaggerated.

"They've overstated the problem," she said. "Refusal summonses are actually fairly low when you consider the hours people work and the trips they complete."

The alliance has released its own proposal to spur rides in the outer boroughs. Desai said the Taxi and Limousine Commission needs to first approve a fare hike, which would make trips to Brooklyn or Queens more economical for drivers.

The alliance submitted a fare proposal to the commission last week. It includes a 50-cent increase for mileage cost, from $2 to $2.50, and a 10-cent increase in the waiting time fare -- from 40 cents to 50 cents. For the night surcharge, which runs from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. daily, the alliance proposes a 50 cent increase, bringing it up to $1. The drivers are also asking for the first time for a morning rush hour $1 surcharge.

The Taxi and Limousine Commission has two months to consider the proposal, Desai said. If they decide to move forward with it, it would then have a hearing and eventually go to the commission for a vote.

To further increase service in the outer boroughs, Desai said the city should create pick-up stands around commercial or nightlife areas.

Back in January, the administration proposed allowing livery cabs to pick up street hails in the outer boroughs as a way to increase service. The practice is currently illegal -- livery service must be prearranged.

After the yellow cab industry and some City Council members expressed opposition, the administration went back to the drawing board.

Currently, said Taxi and Limousine Commissioner David Yassky anything is on the table. He is meeting with stakeholders to consider proposals -- from creating a new class or outer borough medallion to upping regulation of livery cabs.

"Our bottom line goal is to get decent taxi service in all five boroughs," Yassky said. "We're working daily with elected [officials] both in the City Council and the State Legislature to hash through the details of the plan that gets us the service we want."

South Jamaica Rezoning

In addition to the taxi legislation, the council also approved its largest rezoning, covering South Jamaica. The rezoning would preserve the area's low-density character, officials said, but also allow for larger building heights on main thoroughfares.