The State Budget's $38.5 Billion Transportation Program

The on-time New York State budget approved by the legislature on March 31 included a $38.5 billion transportation program covering the next five years, to be split equally between transit and highways.

Legislative approval – assuming the governor does not use his veto pen to make any substantial changes – means that the Second Avenue Subway and the Long Island Rail Road link to Grand Central Terminal will begin construction. The budget also means that the transit system will continue to be maintained and upgraded, although possibly with a stretching out of some projects. It also means that while bridge and pavement conditions on state bridges and highways will not deteriorate, congestion will continue to worsen. Finally, the way the budget was financed means that in 2010, New York will face the same hard financing issues that it confronted this year.

Let’s look at how the $38.5 billion breaks down, starting with funding for the Capital Program of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and then the Highway Program of the New York State Department of Transportation. (NYSDOT).

MTA CAPITAL PROGRAM

System Improvements

Let’s start with the MTA’s “Core Capital Program.” The core program covers what is artfully termed “state of good repair” and “system improvements.” These refer to normal replacement and maintenance of rail cars, buses, tracks, signals, stations and the host of infrastructure items required to keep the subway, bus and commuter rail systems in good running order. The benefits of many “state of good repair” elements are readily seen by transit riders. New subway cars, for example, improve the riding experience and are less likely to break down.

But much of this program is unseen – until disaster strikes. The Chambers Street fire late last year illustrated the importance of modernizing signal systems, for example. Sometimes unnoticed, the system-improvement component of the program goes well beyond keeping the system in good repair. New train control and communications systems, for example, now being tested on the L line and scheduled for installation on parts of the F in the next few years, include signage that will announce when the next train will arrive.

Last September, the MTA requested $16 billion for the core program and $500 million for security, for a total of $16.5 billion. The legislature approved $15.4 billion. In discussions with the legislative leaders, the heads of New York City Transit and the commuter railroads apparently said they could live with the lower amount. How they will do so remains to be seen and thus, whether there are real impacts from this $1.1 billion reduction is unclear. The agencies may stretch out certain program elements, for example, or find ways to cut back on project scopes. Megaprojects

Next up are the widely-heralded expansion projects. These include the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access, which would bring Long Island Rail Road trains into Grand Central. The MTA requested $1.4 billion to begin construction of the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway, which will run from 125th Street to connect into the existing subway line at 63 Street. The MTA also requested $2.3 billion for East Side Access. The legislature approved $2.1 billion for the two projects -- $1.1 billion for East Side Access and $1.0 billion for Second Avenue. The $2.1 billion assumes that the federal government contributes $1 billion.

The approved funding level for these megaprojects means three things.

First, it means that the projects are moving forward. Construction will start during this Capital Program so you can expect that the Second Avenue subway will be built in your working lifetime (unless you are very close to retirement).

Second, don’t buy your tickets quite yet. The funding reductions mean that the projects will open somewhat later than had been planned. East Side Access will open probably in 2015 instead of 2011 or 2012. Second Avenue will also be pushed back, although it’s not clear how far or to when.

Finally, the way the funding is structured will create greater financial pressures down the road. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) requires that funding be identified up front before it approves federal assistance. In this case, state officials will request permission to “pay as you go,” having just enough money identified to meet the cash needs of the project. The federal agency appears likely to accept their request, although positive action is not certain. What this arrangement means, however, is that state officials will have to identify additional funding sources by the time the next Capital Program comes up for approval.

The legislature also approved $2 billion for the #7 extension, but that entire sum is to come from New York City sources. Finally, there is $400 million for the proposed rail connection between JFK Airport and lower Manhattan, a project that is still substantially unfunded.

MTA PROGRAM FUNDING

Transportation Bond Act

The most-publicized aspect of program funding is the $2.9 billion Transportation Bond Act that will go on the ballot for approval this fall. Proceeds from the Bond Act will be split equally between the MTA and the Highway Program.

Unlike in 2000, when advocacy and civic organizations were lukewarm toward a $3.8 billion Bond Act that failed to win voter approval, these groups are now solidly behind this proposal. They are likely to mount a strong publicity campaign to gain voter approval. The electoral calendar is also in their favor. The mayoral contest is likely to draw voters to the polls in New York City, where voters are likely to back the Bond Act by a large margin.

Tax and Fee Increases

The legislature also approved about $300 million in tax and fee increases to help finance the MTA program. These increases include a 1/8 percent increase in the sales tax, which will end up being 8.375 percent in the MTA service region after a temporary increase expires. The increases also include hikes in vehicle title fees and the mortgage recording tax.

Proceeds from these increases will leverage $4.2 billion in new bonds to be used in the MTA Capital Program.

Financing – A Fare Increase? Jets Stadium Sale?

The legislature also approved just over $3 billion in MTA bonds, a sum that is apparently in the MTA’s financial plan from last fall. Thus, as expected, the MTA’s debt burden will continue to grow, placing continued pressure on the fare. Warnings of a fare increase every two years could easily come to pass.

Other elements of MTA funding are $1.4 billion in asset sales (West Side rail yards/Jets stadium, Brooklyn rail yards/Nets stadium, and some other asset sales and revenues), the $1 billion from the federal government for system expansion, and several hundred million dollars in assistance from the city.

Looking Over A Cliff After 2010

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the financing is that only about $5 billion of the $17.9 billion program is continuing funding. In 2010, the MTA will once again be looking out over a cliff, wondering how in the world it can come up with roughly $12 billion for the next Capital Program. Once again, options will be to further increase the debt load, increase taxes, sell assets, etc. So, while the legislature has squeezed out enough funding to get the MTA through the 2005 to 2010 period, funding issues are by no means going away. Each time, of course, the issues become more difficult because some of the options were used up in the previous round.

HIGHWAY PROGRAM

In March, New York University released a report that I wrote assessing highway and bridge conditions and congestion levels in the New York area and capital funding needs for 2005-2010. The report showed that at current funding levels, bridge and highway conditions are likely to deteriorate and congestion will continue to worsen. The assessments of funding needs were striking – an additional $1.3 billion in the New York area alone just to prevent worsening of bridge and pavement conditions and a doubling of the program to meet a reasonable definition of “state of good repair.”

The governor proposed a $17.4 billion statewide program, although funding sources were identified for only $15.4 billion. The legislature approved $17.9 billion, matching the MTA program. (As the notion of matching took hold in Albany, highway advocates suddenly became advocates of transit funding as well.) With few details available, it is not clear how much of the $17.9 billion will be allocated to the New York area. Assuming allocations similar to historic patterns, however, it appears that the funding is barely sufficient to keep road and bridge conditions the same as they are currently.

That would leave only a few dollars for the “mobility” program, which includes added highway capacity, elimination of bottlenecks, bus lanes and similar steps to reduce congestion. While many New York City residents can avoid highway congestion by taking the subway, congestion is unavoidable for the movement of goods in the city and for most suburban residents. By not dealing with the problem, state officials are allowing congestion to be an increasingly significant drag on the region’s economy.

ASSESSING THE BUDGET

There are good reasons to be pleased with the Legislature’s transportation budget. The legislature provided sufficient funds to keep the transit system in good condition and prevent highway and bridge conditions from worsening. Two megaprojects, the Second Avenue Subway and LIRR link to Grand Central Terminal, are going to proceed. In a state where an on-time budget makes front page headlines, these achievements are worthy of praise.

But as Elliot Spitzer recently noted, the budget does not solve New York’s long-term financial challenges.

While coming up with the cash to start the megaprojects, for example, it leaves until the next round in 2010 how to pay for them fully. It loads increased debt on the MTA, ultimately to come out of fares paid by transit riders. And it fails to address long-ignored problems with congestion on the region’s highway network.

So while this budget can be seen as a step forward, the journey won’t be any easier from here.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Parking

Tavi Fields, a 25-year-old rapper, found the city's alternate side parking regulations more than she could handle. "I was going through a hard period of time for a while, where I slept in for most of the day," Fields told the Daily News. While she stayed in bed, her Lexis remained on the wrong side of the street. The result: 90 tickets now totaling $10,433, making her, by the paper's reckoning, one of the top 10 parking scofflaws in the city.

Most New Yorkers manage to avoid such a dubious distinction, but for the people who own the 1.9 million cars registered in the city, parking borders on an obsession. Its rules have spawned at least one novel, a guidebook, sitcom episodes, and two companies dedicated to helping New Yorkers outsmart traffic enforcement officers.

Parking presents elected officials with a quandary. Many New Yorkers with cars view a free space to park as a God-given right. But other New Yorkers, pointing to pollution and congestion from automobiles, object to any move that encourages driving. The city's need for revenue from parking further complicates the picture, along with politicians' natural reluctance to attract the ire of voters who get tickets.

These issues arise again and again - in the controversies over parking at the West Side stadium and the proposed Nets arena in Brooklyn and the debates over the future of city neighborhoods. (See related stories on Flushing and Bay Ridge.) The latest imbroglio is an election year tiff over the use of parking meters on Sunday, which the mayor's critic dubbed "pay to pray."

Most New Yorkers would say the problem is too many cars chasing too few spaces. But some planners disagree. The problem, they say, is not that parking is too expensive, but that it is too cheap. And some say the problem is not that there are too few spaces but that there are too many.

THE HIGH COSTS OF CRUISING

Paying for space in a parking garage, George tells Elaine as they seek a space on an episode of Seinfeld, "is like going to a prostitute. Why should I pay when, if I apply myself, maybe I could get it for free?"

Many New Yorkers apparently agree, and so spend long periods of time driving, in concentric circles or zigzags, looking for parking.

Even the smartest among us do this silly chore. In a 2000 interview, Horst Stormer, a Nobel Prize winner in physics, described his formula for finding parking spaces by scooting ahead of rival drivers.

The average cruising time for a parking space in some New York neighborhoods approaches 14 minutes, according to a 1993 study. That's twice the time spent in San Francisco, where it is so hard to park that residents leave their cars on the sidewalk.

But cruising takes up more than time. Environmentalists cite a 1984 study that found drivers in one 15-block neighborhood in Los Angeles spent 100,000 hours cruising, wasting 47,000 gallons of fuel and producing 700 tons of carbon dioxide emissions in a single year.

New York's rules complicate the process. Moving the car from one side of the street to the other is not required in every city. And any single spot can have three sets of rules governing its use at various times.

Such parking regulations attempt to address a variety of needs, according to Michael Primeggia, the Department of Transportation's deputy commissioner for traffic operations. In most of the city, the main concern is street cleaning, which dictates the alternate side rules.

But in busier commercial areas, particularly in Manhattan, other considerations come into play, such as the need to accommodate traffic flow and allow for deliveries. "New York City is not so lucky that there can be one regulation that regulates the curb for the entire day," Primeggia said. And that leads to two or three signs - with different rules - for a single space.

A WALKER'S CITY, DAMAGED BY PARKING

Ironically, the city famed for its convoluted parking rules and parking headaches is the only American city where a majority of residents do not own cars. This gives rise to a chicken and egg debate. Do New Yorkers not own cars because it is so hard to park? Or is it so hard to park because New York remains a pedestrian and mass transit city that has not destroyed itself to accommodate the automobile?

The number of cars registered to New Yorkers has declined by about 5 percent since its peak in 2000. According to the 2000 Census, 54 percent of all New Yorkers -- and three out of four Manhattan residents -- do not own a vehicle.

But cars still clog Manhattan streets. Although the number of auto trips into Manhattan dropped after September 11, 2001, it has begun to grow again. Some experts predict it could reach 1 million vehicles a day.

A majority of people in Brooklyn and the Bronx do not have cars, but two out of every three Queens residents and four out of five Staten Islanders do.

By some measures (.pdf format) , New York is the second most congested - after Los Angeles - of America's largest cities. In 1990, the average speed of crosstown traffic in a car fell to 5.2 miles per hour. Brian Ketcham, a Brooklyn transportation consultant, estimated then that traffic cost the city nearly $30 billion a year in losses in employee productivity, accidents, air pollution, noise and roadway damage. And a 2004 study concludes that congestion cost the metropolitan area more than $7 billion in wasted time and fuel alone.

HALF A BILLION DOLLARS OF PARKING TICKETS

Many New Yorkers decide not to own a car at least because parking costs so much - particularly for drivers who get a lot of tickets. City drivers paid $537 million for parking violations in 2004. This came from some 10 million tickets, a 20 percent increase from 2003.

Primeggia says parking regulations are not designed to produce revenue or to confuse drivers. Any average citizen who reads English should be able to figure where and where not to park. When there is more than one sign applying to a space, the city puts the most restrictive sign on top. "All it takes is reading the signs in order and determining which sign is in effect," Primeggia said

But not everyone agrees. Louis Camporeale said he became aware of the faulty enforcement of traffic regulations in the 1980s. As a student, he would try to park at broken meters. "Three or four dollars in meter money was a couple of hours work," he recalled.

But sometimes the plan backfired, and he got a ticket -- an unfair ticket. (You can park at a broken meter -- but only for an hour.)

Such disputes led Camporeale to become an advocate for New York City parkers. He has written "The New York City Motorist's Guide to Parking" and runs a web site www.parkingpal.com with parking tips. "New Yorkers think they're so savvy, but when it comes to parking regulations, they're not," he said.

Glen Bolofsky, the author of the city's first alternate side parking calendar, now runs a business www.parkingticket.com that fights people's tickets - for a fee. Its successful challenges arise from confusing signs, mistakes on the ticket itself and other gaffes by the city. The company, which also operates in Boston, San Francisco, the District of Columbia and Philadelphia, claims that it won dismissals or reductions on 75 percent of the tickets it challenged last year.

"The rules and regulation are pretty much stacked against the average person," Bolofsky said. "The city goes out of its way to create a situation to intimidate and bully people."

Although the city consistently denies setting quotas for parking agents, Bolofsky disagrees. "The city budget dictates what the revenue [from parking tickets] is going to be," he said.

THE DEMISE OF THE PARKING LOT

People risk tickets to park on the street, though, because lots and garages cost so much - and the fees seem likely to rise even higher.

A reserved space in a garage in midtown cost $496 in 2004, the highest rate in the country, according to a recent survey. This has prompted some developers to offer parking condos where people purchase a space for tens of thousands of dollars and then pay a monthly fee.

But, despite this, lots are closing as New York's real estate boom makes land too expensive to park on. The city owns lots, but when the land becomes valuable, sells them for other uses. (See related story on Flushing.)

The same thing is happening with private lots. Broker Anne De Marzo told the New York Times that she has sold five parking lots and two garages in the Hudson Yards area with 20 more deals in the works. And Sean Sweeney, director of the civic group SoHo Alliance said he counted 2,000 parking spaces that had been lost in his area. Owners say they can sell their property for $350 for each "buildable" square foot.

POLITICS AND PARKING

In Calvin Trillin's novel about parking - "Tepper Isn't Going Out" �fictional Mayor Frank "Il Duce" Ducavelli sees his poll numbers rise after he goes after the "scofflaws in striped pants" - Ukrainian diplomats who did not pay their parking fees. Trillin obviously drew his inspiration from Mayor Rudy Giuliani's attacks on United Nations diplomats who parked illegally and used diplomatic immunity to avoid paying their tickets. While the problem has eased, New Yorkers still hold a special animosity for foreigners who park freely and illegally, and politicians continue to use that sentiment to their advantage.

Similarly, because alternate side parking rules have few fans among voters, City Council has added to the list of days when rules are suspended, aiming the dispensations at various religions and ethnic groups. In 2002, for example, the council voted unanimously to suspend rules on Asian Lunar New Year, Purim and Ash Wednesday, overriding the mayor's veto.

This year's political parking dispute concerns the use of meters on Sundays -- something the city has done in recognition, it says, of the fact that stores now stay open on Sunday. The move also brings in about $7 million a year.

But a Bay Ridge minister complained that parishioners were ducking out during services to feed the meters. In response, City Councilmembers Vincent Gentile and Hiram Monserrate introduced a bill that would ban metered parking on Sunday. (See related story)

Other Democrats picked up the cause. "There shouldn't be a tax on worshipping," mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer said. "People shouldn't have to pay to pray."

The city has done a done a few things on parking that have met with general approval, particularly the use of multiple space meters. Rather than feed coins into a metal meter on a post, motorists purchase a ticket from a machine and then leave it on their dashboard. Cars can then park more tightly. The system also enables the city to charge different prices at different times or discourage long stays.

Currently, Primeggia said, many of the meters charge $2 for one hour but $9 for three hours to spur turnover. "We're encouraging them to use it as long as they need it, but when they're done leave," he said.

The city also addresses parking in zoning decisions. Residents often cite increased parking difficulties as a hallmark of rapidly developing - or overdeveloped - neighborhoods. So, on Staten Island, for example, the city has increased requirements for parking to accompany new buildings. Of course, more space for parking can mean less land for other uses, including lawns and gardens.

PARKING AND NEW PROJECTS

Concerns about parking also enter into one of the year's hottest political controversies: the proposed Jets stadium on the Far West Side. The extension of the No. 7 subway line aims to make the proposed West Side football stadium friendly to transit users and discourage automobile use. The Jets anticipate 70 percent of people attending games will arrive by mass transit. This would require parking for 7,000 cars.

And an anti stadium group, the New York Association for Better Choices, sees that number as unrealistic. It predicts that each Jets game would attract 16,000 cars and 100 buses, requiring 70 acres of parking lots and garages.

For the short term, the city has said it plans to allow approximately 1,500 new spaces near the railyards. Eventually, it says, thousands of new parking spaces would be provided to accommodate the residential and commercial development of the surrounding area.

Parking is also a concern for the Nets arena in Brooklyn, which, like the Jets Stadium, aims to be accessible by mass transit. The arena plans call for 3,000 parking spaces but critics say this will not be enough. And, they charge, an already congested area will grow more crowded as thousands of Nets fans cruise the streets looking for parking.

Parking is such a problem for new projects that developers want even racecar fans to get out of their cars. The proposed NASCAR track on Staten Island would accommodate about 95,000 people, but the plan only calls for parking for 8,400 cars. International Speedway Corp. hopes fans will park at some 16 off-site lots and take shuttle buses to the track.

PAYING TO PARK

Even though parking is a cherished commodity in New York, the city gives it away. A 2002 survey found that only 24 percent of the almost 30,000 curbside parking spaces in Manhattan south of 59th Street had meters.

Donald Shoup, a professor at University of California Los Angeles, argues in his new book "The High Cost of Free Parking" that free parking creates many costs, helping to explain "extreme auto dependence, rapid urban sprawl and extravagant energy use." Just charging $1 an hour for those unmetered Manhattan spaces, he said, would generate $250 million a year.

"People are paying a very high cost for housing and people even go homeless and cars are parking for free," he said.

Shoup believes the city should set rates for on-street parking high enough so that about 15 percent of the spaces are usually unoccupied. In some areas of London, this is eight pounds -- about $15 -- an hour.

To make such a sharp increase in rates politically palatable, Shoup proposes the money go to local community agencies to fund neighborhood improvements. "Nobody ever wants to pay for parking, so you have to create someone on the other side of the meter who wants the money," he said.

Some critics say such policies are unfair to lower income people. And while this is less true in New York City than other places, businesses worry (.pdf format) that high priced parking will keep people from driving to their establishments and spending money.

Some cities, though, have taken more drastic measures to stop parking. Copenhagen for example has a policy to reduce parking by about two percent a year.

That would be fine with Kit Hodge, campaign director of Transportation Alternatives, as long as people take transit, bike or walk instead. "Our aim is to discourage parking," she said.

For More Information

Organizations

New York City Department of Transportation

Alternate side parking, other parking regulations and how to pay a ticket online.

Parking Pal

Information and tips designed to help drivers park in New York City

Transportation Alternatives

An advocacy groups that seeks to reduce automobile use. Its web site includes information on car and bicycle parking.

Resources

Colliers Parking Rate Survey (in pdf format)

A survey of how much it costs to park in 55 North American cities.

Gridlock Sam

Web site run by former New York City Traffic Commissioner Sam Schwartz with information on parking, driving and congestion in the city.

parkingticket.com

Company that will fight your parking ticket - for a fee.

2004 Urban Mobility Study

The Texas Transportation Institute's study of mobility and traffic congestion on freeways and major streets in 85 cities.

Articles

The Autonomist Manifesto (Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Road)

(New York Times Magazine)

A Brief History of Parking: The Life and After-life of Paving the Planet

(Architecture Magazine)

The Dynamics of On-Street Parking in Large Central Cities

(Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management, NYU)

Fewer Cars (Same Traffic)

(Gotham Gazette)

The High Cost of Free Parking

(Donald Shoup)

The site includes the book's first chapter, articles on the book and comments by the author.

High Costs Drive Car Owners Crazy

(Daily News)

NYC Parking Policy is Backwards and Dangerous

(Transporation Alternatives magazine)

No Parking. You're Welcome

(New York Times)

The Overdevelopment Debate

(Gotham Gazette)

Parking Space and Public Spaces: Why Parking Can Destroy Communities and How to Find a Place for It

(Project for Public Spaces)

The Savvy Parker

(New York Chapter, American Automobile Associatin)

Shakedown: Sometimes It's the Little Things that Drive Your Over the Edge

"Tepper Isn't Going Out" by Calvin Trillin

(Salon)

Discusses the novel about parking in New York

Ticketing Blitz?

(Gotham Gazette)

Fewer Cars (Same Traffic)

What’s going on with auto ownership and traffic in New York City?

News reports in February highlighted an 8.4 percent decline in the number of registered autos in the five boroughs between 2000 and 2003. Vehicle registration data posted on the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) website in late February show a further 1.6 percent decline from 2003 to 2004.

Ex-car owners and various experts offered a assortment of explanations for the decline in registrations. Rising costs of owning a car was one favorite. A research firm quoted in Crains New York estimated that car ownership costs rose 15 percent since 2001. The cost of parking in Manhattan garages is climbing, as are gas prices. Fines for parking violations increased 30 percent in 2004, spurred by a 20 percent increase in the number of tickets issued.

A Newsday article cited not only costs but also the scarcity of parking spaces and the soaring costs of housing, which consumes a larger share of the household budget.

Another possible explanation is that more people are registering their cars out of town. However, while the streets are sprinkled with parked cars sporting out of state license plates, it is not clear that the number is increasing.

A Department of Motor Vehicles spokesman suggested that maybe more people are ditching their cars and using mass transit. Indeed, in 2004 subway ridership hit its highest level since the mid-1950s, with 1.4 billion riders passing through the turnstiles.

Funny thing is that the decline in vehicle registrations has not made finding a parking space any easier. Nor has it reduced traffic congestion. Although auto traffic into Manhattan dropped after 9/11, the number of vehicles entering Manhattan showed renewed growth in 2004. According to the NYS Transportation Department, total vehicle miles of travel in the New York region increased in 2001 and 2002 despite the effects of 9/11. (Figures since 2002 are not available.)

So if traffic is up and auto registrations are down, what’s going on?

Part of the answer is undoubtedly that it’s not the high-mileage drivers who are selling their cars. An ex-car owner quoted by Newsday said that in order to avoid losing her curbside parking space, she hardly ever used her car. Drivers stuck on the Gowanus “Expressway” did not see her before and won’t be missing her now.

Most likely it is the occasional drivers who finally decided that they could simply do without their cars. These would seem to be the folks who bought an unlimited ride Metrocard and so “ride free” after hours and on weekends. They can use transit and the occasional taxi ride as their wheels to move around the city.

Another part of the answer is undoubtedly the economy. Car registrations dropped during the early-1990’s recession and then bounced back during the boom years of the late-1990s. While registrations continued to decline in 2004 even as the economy began to turn around, the rate of decline was less than in the prior two years.

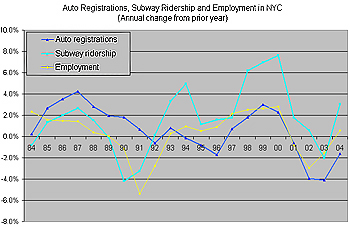

Whether the ranks of auto owners grow again remains to be seen. There has, however, been a fundamental shift from auto ownership to subway ridership. While auto registrations and subway ridership both rise and fall with the economy, as the chart below shows, prior to 1992 auto registrations grew more quickly than subway ridership (or declined by a lesser percentage). It was a consistent pattern evident year after year.

But since 1992, subway ridership has grown more quickly (or declined by a lesser amount) in every year – even years that there was a transit fare increase. On the margin, then, more people are plunking down money for their Metrocards than for their vehicle registrations.

This reversal of fortune does not mean that the city’s roads and highways are likely to be cleared of traffic congestion anytime soon, or that drivers will spend less time circling the block to find a parking space. But it does suggest that there is a viable choice, one chosen by more and more New Yorkers -- taking the subway.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â