(image via New York City's City Planning Department)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

“It might seem early, but given the challenges that are facing the decennial census in 2020, it’s not early enough,” said Steven Romalewski, director of the mapping service at the Center for Urban Research, CUNY Graduate Center. Advocates, government officials, and members of the business community all agree with that sentiment, that early preparation is essential if New York is to ensure a full accounting of its population in the 2020 Census, wherein the stakes are immense.

The census, the federal government’s constitutionally required every-ten-year count of residents of the United States, forms the basis for each individual state’s electoral representation, both locally and at the federal level, determines levels of federal funding states receive each year, and underpins dozens of human-facing programs carried out by state and local governments. Officials and advocates in New York City have already begun to marshall resources as they prepare for the nearly two-year effort that lays ahead, but the state has yet to pick up its feet despite a looming deadline.

Many view 2020 as a particularly challenging year for the Herculean effort of carrying out the census. Besides the usual logistical challenges of reaching hard-to-count communities, 2020 is set to see lower-than-expected funding from the federal government, a shift towards digital methodology, and the inclusion of a citizenship question, though it is the subject of ongoing litigation spearheaded by New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood. All that comes amid a heightened atmosphere of anxiety among minority and immigrant communities who fear the repercussions of being counted by a federal administration overtly hostile to their interests while already being most likely to be undercounted.

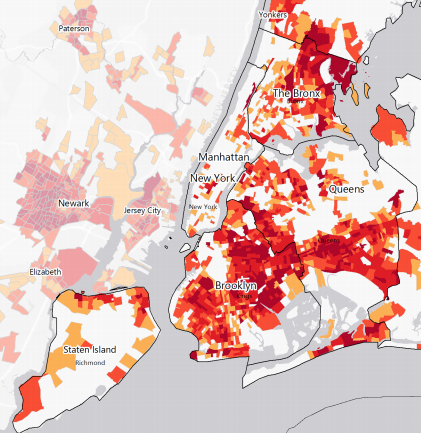

In each census, the federal government has to work hand-in-hand with local counterparts to reach hard-to-count communities, those where at least a quarter or more of households do not fill out the initial census questionnaire sent out by the Census Bureau. In New York State, 75.8 percent of households responded to the 2010 census, according to estimates by the CUNY Graduate Center, which worked with civil rights organizations across the country to create maps of census tracts to identify hard-to-count communities. The rest must then be counted in person by the thousands of enumerators hired by the Census Bureau, a labor- and time-intensive process that includes a lot of door-knocking and also requires additional resources and funding.

Advocates and experts warn that the Trump administration’s underfunding of the Census Bureau and attempt to include a question about citizenship may lead to a grossly inaccurate count, the effects of which will be felt for the better part of the decade before the next census in 2030 and could hit New York, especially New York City, particularly hard. An undercount can cement the problems faced by the most vulnerable members of society -- seniors, children, the homeless, for instance -- and exacerbate them by creating a false dataset based on which government crafts policy and budgets.

City officials already recognize these challenges that lay ahead. Deputy Mayor for Strategic Policy Initiatives Phil Thompson is leading the de Blasio administration’s broad census outreach efforts, coordinating with partners in state government, community-based organizations, and the private sector, which is particularly involved in the current census cycle. Thompson pointed to two main outreach targets: immigrant communities and black communities.

“In immigrant communities, it’s always a challenge to get a good count in New York City because it is so diverse,” Thompson said in a phone interview. “There are so many immigrant communities, which people may not even hear about sometimes. [The questionnaire is] not in their language. They’re new. They get skipped.”

The Census Bureau currently only translates its questionnaire into about 20 languages, he said, and New York City residents speak more than 100. The city has already allocated about $4.3 million to its census efforts in the current fiscal year, ending June 30, 2019, which will be used to conduct outreach through ethnic media, Thompson said.

But the bigger fear among the large undocumented immigrant population that resides in the city is that census answers may be passed on to immigration enforcement authorities, even though that is prohibited under the law. “Now, the law prohibits passing information on from the census to any other agency and individual data is not allowed to be passed on, but folks are scared anyway,” Thompson said.

But the bigger fear among the large undocumented immigrant population that resides in the city is that census answers may be passed on to immigration enforcement authorities, even though that is prohibited under the law. “Now, the law prohibits passing information on from the census to any other agency and individual data is not allowed to be passed on, but folks are scared anyway,” Thompson said.

[pictured: New York City census hard-to-count map, via CUNY Graduate Center Mapping Service]

Black communities, the other main target of the city’s efforts, have had historically low rates of filling out the census, Thompson noted. “That goes for people who live in public housing or in low-income housing. Many people may have an extra person living in the house and they’re afraid that the census comes and does a count of who’s in the household, they may get in trouble...And then some mysteries. We don’t know why middle-income and upper-middle income black people in Southeast Queens don’t fill out the census, but historically they’ve had low rates as well.”

2020 will also mark a major shift in how the census is carried out, with a greater reliance on digital technology. As opposed to the past method of sending out the questionnaire by mail, the Census Bureau will send out a digital code by mail, encouraging people to fill out the questionnaire on the Census Bureau’s website.

When people do not respond, they will be sent a full paper questionnaire to mail back. People can still request a paper questionnaire, particularly if they lack easy access to the internet. “And that’s a challenge because not everybody utilizes iPads and computers,” Thompson said. “Not everyone’s on the internet. So in communities with low broadband access, they are more likely not to fill out the census.”

In response, the city plans to set up help desks at public libraries and schools to facilitate access, with several public-facing city agencies such as the Department of Education and Department of Homeless Services also involved in the effort. The de Blasio administration is encouraging the private sector to provide financial assistance to community organizations and will also put more funding into hiring immigration lawyers at immigrant affairs offices. The city will also hire 13 district office directors to match the 13 offices being set up by the Census Bureau across the five boroughs, and is helping recruit for the 20,000 or so enumerators that the Bureau will hire to conduct door-knocking and outreach in hard-to-count communities in the city. According to the Bureau’s estimates, they will need roughly 44,442 enumerators for the entire New York region. There are also jobs under the city’s Summer Youth Employment Program focused on democracy and the census, training young people between the ages of 16 and 24 to organize in their communities.

“We’re also telling people if you don’t like what’s going on in terms of a lot of this anti-immigrant rhetoric and so forth, the best thing to do is to not go and hide in the shadows but stand up and be counted,” Thompson said, touching upon the challenge involved in convincing people already wary of the Trump administration to trust that administration’s census process.

Community advocates, in particular, are aware of the pressing need to ensure an accurate count. Liz OuYang, coordinator of New York Counts 2020, a statewide coalition of community organizations, said the upcoming census would be a “heavy lift” compared to 2010. “More than ever, community-based organizations are going to be needed as trusted organizations that people can go to in light of the political climate,” she said. These groups are particularly vital in reaching undocumented immigrants who are fearful or skeptical of the federal government.

Ahead of the 2010 census, community organizations in New York City received only about $2 million in total from private sources, OuYang said, leading to an undercount. This time around, the coalition is pushing the city and state to fund phone-banking and door-knocking operations. They are urging legislators to agree to that demand and plan to rally in Albany, the state capital, in March, ahead of the passage of the state budget.

The coalition is also aiding local Complete Count Committees, including by creating a census training webinar for the committee recently launched by Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and the Brooklyn Community Foundation. “Because of the undercount in 2010 and because of the macro-political climate that we’re in, and the census being allowed to be completed online, you’re going to need a lot of help from community-based organizations,” OuYang said.

The federal government appropriated about $2.8 billion for the Census for the 2018 fiscal year, which ended September 30. But the Census Bureau has requested only about $3.8 billion for the 2019 fiscal year, which most experts and stakeholders believe is inadequate. Across the country there are expected to be 200,000 fewer enumerators, who conduct the on-the-ground follow up, because of the lower funding. What’s more, unlike past census efforts, the federal government appears unlikely to approve a waiver that would allow the Commerce Department to hire non-citizens to act as census enumerators in order to reach hard-to-reach communities. Such a waiver was approved by the administrations of Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush.

“We don’t know if Trump will do a waiver and if not that’s a problem,” said Deputy Mayor Thompson. “So we’ll have to lean in as a city to get the right people because the most trusted messengers in communities that are fearful are people from the communities.”

In an email, Census Bureau spokesperson Kristina Barrett said the agency was working within the restrictions of the annual appropriations act. “There is not a ban, and we are still pursuing all legal flexibilities provided by Congress to hire the workforce we will need to conduct an accurate 2020 Census,” she wrote. She said the Bureau is allowed to temporarily employ translators under certain exceptions and can hire permanent legal residents applying for U.S. citizenship, people admitted as refugees or granted asylum who have filed a declaration of intent to become a permanent resident and then a citizen when eligible.

To make up for the expected shortfall in enumerators, particularly in undocumented communities, the New York Counts coalition is pushing the state government to ensure adequate funding for counting efforts. A study from the Fiscal Policy Institute, commissioned by the coalition, estimated that need at about $40 million, roughly $2 for each of New York’s 19 million residents. But so far, the state has made no commitment while the city’s $4.3 million is something, but far from adequate. (The city is expected to add more funding in the next fiscal year which begins July 1, 2019.)

“Without funding, community-based organizations are not, that’s the bottom line, are not gonna be able to do full outreach,” OuYang said. “And it takes community-based organizations, trusted organizations in the community to really mobilize people and be the bridge here.”

In the current fiscal year, Governor Andrew Cuomo and the state Legislature approved the creation of a New York State Complete Count Commission, which is meant to study past undercounts and issue a comprehensive action plan for 2020 by January 10, 2019. But with just over a month till its report is due, that commission has yet to be formed, raising concerns that the state is dragging its feet. “I think that the governor needs to prioritize this, this is huge,” OuYang said.

A spokesperson for Cuomo said in an email that the commission is in the final stages of being assembled but did not provide any personnel details or proposed budget numbers. “A complete and accurate count is critical for New York to receive proper representation in Washington and our full allocation of federal funding, and the State is committed to being a full partner in a robust outreach effort so that every New Yorker is counted,” the spokesperson said.

The state has, however, been using data analytics to ensure that the Census Bureau’s Master Address File, which will dictate where the initial census questionnaires are sent in March 2020, is complete. According to the governor’s office, addresses in the MAF were compared to state databases and agency records and hundreds of thousands of corrections and additions were submitted to the Census Bureau for review this past summer. There have also been 40 meetings across the state to encourage the creation of complete count committees.

It’s likely that the governor will provide more clarity about the overall census effort in January at his State of the State speech, where he will lay out his broader agenda for the year. His executive budget proposal with funding numbers will follow soon after.

Thompson, the deputy mayor, said he was optimistic about the state coming through and that operations will likely ramp up with the start of the new year. In the meantime, New York City government and members of the business community are picking up the slack.

“So far New York State hasn’t put up a [funding] number and we were actually helping other towns and cities in New York organize their census operations because the state commission on the census hasn’t met yet,” Thompson said. “We’ve had nice conversations and I’m looking forward to working with the state around this, but right now we’re, I think it’s safe to say, ahead of the state.”

He noted that the New York Banker’s Association had offered to make its locations available to get the word out about the census. “I’m most excited about the responses we’re getting from every sector of the city to come together,” Thompson said. “The business community is very forthcoming.”

The Association for a Better New York, a prominent business coalition in the city, announced on December 3 that it had hired Melva Miller, who was previously deputy borough president of Queens, to lead its census efforts, the broad contours of which had been announced previously. “This is an all hands on deck effort,” Miller said in a phone interview.

ABNY has been marshalling resources for nearly a year to assist New York’s efforts. It has been conducting focus groups in hard-to-count communities, gathering data and information on the obstacles people may face. It also launched a poll last week in those communities “to get an understanding of the census and what that means for them.”

The organization will also pull together a larger messaging campaign, also targeted at particular communities, to urge people to fill out the census on their own, “because unless you can really spell out what the implications of an undercount means to folks, people aren’t excited about it,” Miller said. “No one wants to fill out a form...How can you make it sexy? How can you make it exciting so that people know that this is really critical to the health and the quality of life for all of us, especially New Yorkers?”

Miller noted that the implications of an undercount go beyond federal funding -- New York receives about $80 billion each year -- and a potential loss of representation in Congress.

“There’s voting rights and redistricting implications, there’s public and private research on social and economic issues, and something that folks don’t talk about that probably resonates with the private sector is that having reliable and good data dictates how businesses do business,” she said. “So as companies are doing their needs assessments and assessments of areas in which they might want to relocate or expand, they rely on data that talks about the population. Who lives there, what’s their education level. And then in terms of workforce. People love coming and operating in New York because of our talented and diverse workforce. And quite frankly, we’ve benefitted from programs that assist and support that workforce. And all of that is at stake when you undercount a population like New York.”

“There’s voting rights and redistricting implications, there’s public and private research on social and economic issues, and something that folks don’t talk about that probably resonates with the private sector is that having reliable and good data dictates how businesses do business,” she said. “So as companies are doing their needs assessments and assessments of areas in which they might want to relocate or expand, they rely on data that talks about the population. Who lives there, what’s their education level. And then in terms of workforce. People love coming and operating in New York because of our talented and diverse workforce. And quite frankly, we’ve benefitted from programs that assist and support that workforce. And all of that is at stake when you undercount a population like New York.”

Besides the decennial count, the Census Bureau also does the annual American Community Survey, which delves deeper into subsets of census data and then extrapolates that information to make assumptions about the larger population. “It really has a ripple effect,” said Romalewski of the CUNY Graduate Center, one of the area’s top census experts. “If the count is not done well in 2020, that will have an ongoing impact throughout the decade.”

He did note that there was at least one upside to all the challenges posed by the Trump administration, echoing what has been something of a theme on a variety of political and policy matters. “The silver lining in all of this is that there’s a concerted, coordinated effort early on to make sure people understand the importance of the census and that they participate fully,” he said.

The biggest “what if” factor in the entire census process is the legal battle over the inclusion of the citizenship question. The Justice Department is facing off in federal courts across the country against a broad array of plaintiffs including dozens of states and cities, including New York, immigrant advocacy groups, and the American Civil Liberties Union. Both sides issued closing arguments in late November in a trial in federal court in Manhattan -- other trials are on the horizon in other states -- and a judge is expected to issue a decision within weeks. The U.S. Supreme Court also agreed last month to hear arguments over whether Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross can be deposed over how the decision to include the citizenship question was made.

“The thing I worry about the most is the fear tactics succeeding,” said Deputy Mayor Thompson. But he was undeterred even by the prospect that the highest court in the land could rule against the cities and states seeking to protect undocumented immigrants by ensuring they are counted. He likened it to the country’s history of racial segregation and slavery, which were held up for decades by courts and a Congress that maintained both were legal.

“So just having a Supreme Court go against you doesn’t mean you give up,” he said. “What changed segregation was actually when churches, ordinary Americans said enough is enough. And we have to have that attitude now. We’ll fight back...We have a history of fighting for our democracy. It wasn’t given to anybody, we got it through struggle and we might have to struggle again.”

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette