Housing in view (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The United States, and New York particularly, faces a housing crisis of its own making. Today, housing costs are the main driver of inflation, which is leading to painful interest rate hikes across the whole economy. And they’re the main driver of homelessness, an even more acute problem in high cost states like New York and California. In fact, for every $100 of increase in median rent, there’s a 9% increase in homelessness.

High housing costs lead to teachers, police officers, firefighters, and service workers being forced to live far from communities they work in simply to be able to afford a home. As distance between communities and their essential workers grows, so does distrust and lack of cohesion within them. And, housing costs are cited as a major driver of our inability to diversify and grow the economy. In fact, as numerous residents and businesses move to the Sun Belt, cheaper housing for workers is one of the most commonly cited reasons.

Prior localized efforts to build more housing in New York City and particularly its suburbs have failed, captured by NIMBYism (“not in my backyard” opposition) and parochial local politics. New York’s own Regional Plan Association estimates that half-a-million homes could be developed along New York City’s commuter rails alone by allowing housing density on properties already zoned residential, but few suburbs have allowed it.

New housing supply is severely below new housing demand because localities work to oppose new housing through means such as exclusionary zoning, parking requirements, and extended public comment periods that amount to filibusters to run out the clock. In New York, extreme NIMBYism has led to embarrassing episodes such as a recent viral video of a young man speaking in favor of an affordable housing project being shouted down at a Bronx community meeting.

Even in high-opportunity, transit-rich neighborhoods like Soho and Midtown West, you’d be hard-pressed to find many local elected officials who support upzoning their jurisdictions to develop more housing — something that would be very beneficial for the city and society as a whole but where there are hyper-local costs such as construction noise, property value changes, or blocked views.

Too many people presume that hyper-local direct democracy -- where neighborhoods get vetoes over what gets built -- is the American way. Yes, our fundamental unit of government is local, but NIMBYs do not have the sole claim to American history and traditions. For another way forward, look to Federalist 10, where James Madison makes the most forceful case for enlarging the sphere of decision-making so local communities could not kneecap widely beneficial policy.

In short, building housing has become a dysfunctional direct democracy issue – what Madison termed factional. Madison argues that "the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property." Today, the immediate costs of building housing are borne by immediate neighbors in the immediate future, creating political pressures on local officials, community boards, and towns to block housing with infinite delays in hearings and approvals. Coupling these pressures with the fact that voter turnout among homeowners is approximately 25% higher than renters, we have a perpetual public choice problem where our local governance perpetually under-approves housing.

These patterns were foreshadowed by Madison 230 years ago when he wrote “those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society." Thus, Madison argues to combat the effect of faction, we must adopt a national Constitution that enlarges the sphere of interests.

Faced with localities continuously under-developing housing, this is exactly what California did in passing a landmark law at the state level that summarily approved housing as-of-right in underutilized commercially-zoned corridors.

California provided a way forward for New York and elsewhere as part of its effort to address its own shortage of 3.3 million homes by passing a statewide law that provided higher density zoning as of right for underutilized commercial properties (for comparison the New York City metro area alone has 516,000 fewer housing units than jobs and faces a shortage of 560,000 units by 2030 simply to account for current population growth). California’s success was made possible because it bypassed the NIMBYism of localities by building a statewide, broad coalition of business, labor, and housing advocates. The diffuse benefits of more housing were used to marshall public support at the state level even if they would likely fail at a local level where parochial interests rule.

I spoke to the architect of the law, AB 2011, California Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks, about the path to passing such a controversial but important bill. Wicks credited the passage of her bill to the visible failure of decades of NIMBYism with regard to aggregate housing.

“Every freeway ramp encampment, every city, is a visible reminder California has 27% of the country’s homeless population and it’s a very visible reminder of our failure on the housing issue,” she said.

“It takes 5, 6, 7 years to break ground on a project because of red tape and approvals,” Wicks added, and the housing construction industry is one that many people are exploited in and leave.

Her solution was a bill that ties together important pieces: it took as-of-right approvals statewide and out of local hands for specific projects that alleviate the housing shortage while using labor that pays a prevailing wage to bring workers back to the housing industry.

Another major component of the California victory was focusing on commercial corridors in order to sidestep residents who otherwise object to adding density to their current neighborhoods from single family to multifamily, the type of upzoning many reformers focus on most.

According to a quantitative analysis by Urban Footprint that Wicks credits for bringing California’s proposal to life, underutilized commercial corridors targeted by the bill could provide up to 2.4 million new homes, including up to 400,000 affordable to low- and moderate-income households across the state. This while increasing local tax revenues and providing substantial environmental benefits - it is estimated that these new units will produce 50% less greenhouse gas emissions than the average California household due to their density and proximity to already existing roadways, water mains, and sewage.

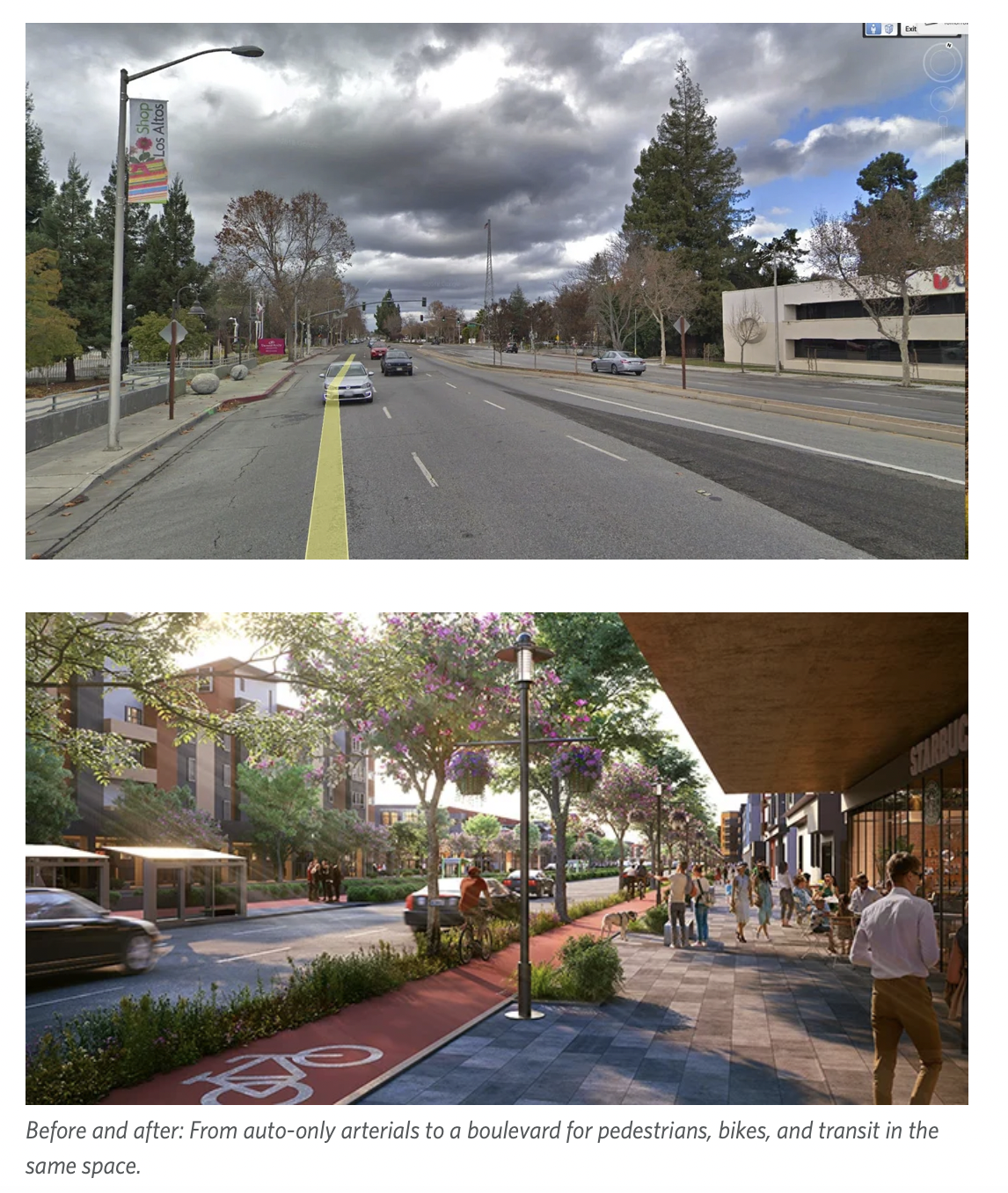

(source: Grand Boulevards: A Plan to Solve California’s Housing Crisis)

California’s new law creates two options for underutilized strip malls and commercial corridors along wide boulevards such as the Bay Area’s El Camino Real. Developers who choose to build 85% market rate and 15% affordable housing can build mixed-use housing with retail on the ground floor as-of-right with only ministerial approval, bypassing local councils and rezoning if they provide prevailing wages, raising the take home pay of people who work in construction and developing a much needed workforce.

Developers who choose to build 100% affordable housing do not have to pay prevailing wage. According to Assemblymember Wicks, starting with underutilized commercial corridors rather than upzoning existing residential zones helped bypass NIMBY opposition in part because people recognize that parking lots and strip malls are not efficient uses of space on major arteries.

(Artist Conception of Commercial Corridor Based on Boulevard Size, Source: Urban Footprint)

California’s landmark housing victory would not have been possible without the broad coalition that realistically could be built at the state level without falling victim to Madison’s “factions” that can capture smaller units of government and politics. Wicks particularly credits support from service and education workers, who are often forced to live hours away from where they work, carpenters’ unions who do not belong to the large building trades but whose work goes primarily to housing, and even Republicans in the Assembly who are traditionally opposed to red tape and regulations. These are not the kind of groups who would necessarily show up to a community board meeting for a single housing development, where the benefits are often too narrow to attract attention and rally those focused on the greater good.

In New York, a similar statewide housing plan could apply to New York City and surrounding suburbs on Long Island and up the Metro North region. The state would designate an underutilized commercial corridor based on the width of a commercial boulevard or along a mass transit artery like the subway, LIRR, or Metro North. They would receive as-of-right mixed-used zoning with appropriate density based on corridor size, with only ministerial approvals in exchange for 100% affordable housing or 85/15% but using prevailing wage construction. Labor, business, and housing advocates would be able to succeed in getting more housing approved through this state level action than piecemeal at the local level.

In New York and across the country, building housing is a necessity. With the Federal Reserve hiking interest rates, there is no guarantee new housing supply will be added to meet demand. It’s a vicious cycle as housing costs now comprise the biggest portion of core consumer price index (CPI) increases year on year, which will continue to push the Fed to painful rate hikes and produce even fewer housing starts.

Now is the time to embrace the Madisonian model and take some decision-making out of the hands of localities that have proven they will not add housing, instead embracing essential growth for the good localities, states, and their residents. It’s a rare issue of bipartisan agreement with bills by Republicans such as Senator Todd Young of Indiana and Democrats like Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey pushing to clear hurdles and red tape to build more housing.

In New York, we ought to take a lesson from Madison and from California’s experience to embrace housing reform at the state level.

***

Suraj Patel is a professor and former candidate for Congress. On Twitter @surajpatelnyc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.