Passing the "Do-Ability" Test

New Yorkers are well aware that lofty promises of elected officials and seemingly well-financed developers often never materialize. So what enabled Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plaNYC presentation to pass the immediate litmus test of "do-ability"?

After all, the Empire State's share of the national population - and political power in Washington that goes with it - is dwindling. In 1960, New York State had 42 representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives; today we have 29. According to a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, New York will lose six more seats in the Congress by 2030. Investments in public housing, mass transit and even sewage-treatment plant upgrades may be harder to realize as the state's share of U.S. population slides from about 7 percent today to about 5 percent.

At the same time, over the next quarter century, New York City's population is expected to increase by a million people, creating critical new needs for housing, transportation, and pollution controls.

When it comes to funding, New York City can not count on the federal government; we must become more financially self-reliant.

But in his plaNYC proposals, Bloomberg recognizes reality and faces these budget issues head-on. The mayor's speech was made more credible because it addressed the demand to "show me the money" that follows a presentation of any vision to New Yorkers. By incorporating the consideration of climate change into the city's planning process, planNYC has the potential to change the playing field of urban development and to deal with the financial challenges at the same time.

The mayor's plan addresses these critical needs in a number of ways:

Energy Conservation

Adopting a surcharge on electricity to pay for improvements in the system will create incentives for consumers to conserve, and at the same time, generate new revenues to fund a comprehensive effort to better educate the public and enable property owners to reduce their reliance on the old polluting energy sources.

Anyone who has ever been to their rooftop can see the hundreds of square miles of black-tar coated roofs that create the urban heat effect, forcing everyone to spend more on electricity at peak times to cool things off. Green roofs and "cool" roofs, which the mayor's plan promotes, cost more, but they are better for the health and financial well-being of the city.

Cleaning Our Waterways

Creating a revolving loan fund for brownfield clean-up, allocating money to greening underutilized street and sidewalk space, and fully funding the tree planting program will help break the cycle of massive stormwater runoff and in some cases infiltration. This can cause toxic contaminants in brownfields to leach out through groundwater and contaminate our waterways where they enter the food chain.

The goal with perhaps the greatest potential to improve water quality in our rivers, bays, creeks and canals is one that most people never see: Developing long-term plans for the more than 400 combined sewer outflows. For generations our solution for preventing our 14 sewage treatment plants from being overwhelmed by storm water runoff has been to simply to build bigger pipes. City water rates have risen 23 percent in the last two years, and they are projected to increase another 23 percent in the coming two years, driven in part by this short-sighted and multi-billion dollar approach. PlaNYC promises to take a different tack and find ways to maximize the volume of rainfall which goes into the ground, rather than adding these more than 25 billion gallons of rain to our already costly sewage treatment processes.

Congestion Pricing

Perhaps the most promising and necessary aspect of the mayor's plan is congestion pricing, through which the new SMART authority will be able to levy a fee on vehicle traffic entering the Manhattan business district during peak hours Monday through Friday. The additional funds raised through congestion pricing will be dedicated to mass transit, including ferries, which for too long have long-suffered neglect by New York's many transportation agencies.

Creating the SMART regional financing authority will help make sure that New York City gets greater say in transportation improvements. Too often the toll increases passed by the MTA and Port Authority at the bridge and tunnel crossings simply disappear into the budgets of other agencies.

It is easy to understand the knee-jerk reactions of garage owners, who are afraid that if fewer people drive into Manhattan then demand for parking will drive hourly parking rates down. But when we think about the fact that all of the pavement and asphalt dedicated to traffic also floods our sewer system because the rain runs right off the road (and costs the city billions as noted above), it becomes clear that every city dweller is already subsidizing these drivers in numerous ways.

Our transportation funding needs became even clearer recently when the Federal Highway Administration announced that in 2009 the Highway Trust Fund will be $21 billion short of what is needed just to maintain the roads we have today.

A Future Vision

Mayor Bloomberg's much-needed initiatives to improve the quality of our land, water, and air will rely on all of our ability to put special interests in their place and put the future of New York at the top of our agenda. From Oak Point to Arverne East, a vibrant New York City in the year 2030 has to start today.

Carter Craft is director of Programming and Operations for the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance and Editor in Chief of www.waterwire.net or email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Â

Will Voting Reforms Discourage Minority Voting?

The recent decision to move New York's presidential primary to February 5 -- which is now being called "Super Duper Tuesday" -- is not only expected to give New Yorkers more influence in choosing the Democratic and Republican nominees, it could also boost voter turnout and increase the power of urban and minority voters.

According to recent report by The Century Foundation early primaries in states like California, Nevada, New Jersey and New York mean that Latino voters in particular, "could not only affect the outcomes, but also the topics the candidates focus on, including wage and labor issues, education and immigration reform."

At the same time, though, because of the debacle in Florida in 2000, new voter identification requirements are being implemented that may have the opposite effect, discouraging minority groups from going to the polls.

Voter identification requirements have become a critical part of the national debate over election reform. Supporters of more stringent regulations argue that voter fraud is frequent enough to justify strict new identification requirements. Others disagree, arguing that the consequences far outweigh the benefits.

"At a time when not nearly enough people vote in the United States, some political players are making it more difficult for people to vote," said Tova Wang, a fellow at the Century Foundation and a co-author of a report on voter fraud now at the center of a brewing controversy. According to Wang, the federal Election Assistance Commission rewrote the report's findings before its final release and issued a gag order to keep Wang from speaking about the report.

VOTER IDENTIFICATION REQUIREMENTS

The 2002 Help America Vote Act (known as HAVA) tried to address voter identification issues by calling for updated voting procedures and technology across the country.

HAVA requires that first-time voters present a state driver's license or the last four digits of their Social Security number at the time of registration. Voters with neither form of identification may use a valid photo ID, a current utility bill, bank statements, government check or any other government document that shows the registrant's name and address. Voters who do not supply this information at the time of registration will be asked for it at polls when they go to vote for the first time.

Although HAVA is a federal program, each state must come up with its own ways of complying with the regulations. New York State's laws largely mirror those of HAVA and are not considered overly burdensome by many election reform experts.

IS FRAUD A REAL CONCERN?

The main reason for the new voter identification regulations, proponents argue, is voter fraud. And they point to news stories that appear after nearly every election relating instances of impersonation, double voting, and even votes cast on behalf of the dead.

But the prevalence of voter fraud depends on who you ask, with Republicans generally arguing that it is widespread and Democrats typically arguing that it is not.

A lengthy, bi-partisan study (in pdf) on voter fraud conducted by the Election Assistance Commission concluded only that the issue has "created a great deal of debate among academics, election officials, and voters" and noted that "past studies of these issues have been limited in scope and some have been riddled with bias."

But that mild conclusion proved to be controversial. The New York Times reported that the editors of the report intentionally revised the findings of the primary authors to reflect the sentiments of White House officials (to view original draft report, in pdf, go here). In a statement released April 26, Wang stated "It has been my desire to participate in this discussion and share my experience as a researcher, expert and co-author of the report. … Unfortunately, the EAC has barred me from speaking." Wang continues, "As numerous press reports indicate, the conclusions that we found in our research and included in our report were revised by the EAC, without explanation or discussion with me, my co-author or the general public. … From the beginning of the project to this moment, my co-author and I have been bound in our contracts with the EAC to silence regarding our work, subject to law suits and civil liability if we violate the EAC-imposed gag order."

There has been little prosecution of fraudulent voting. Since 2000, the Justice Department has charged only 120 people of fraudulent voting. Eighty-six were convicted. This low level of prosecution been cited by some as a possible explanation for the firing of eight U.S. attorneys by Attorney General Alberto Gonzales.

WILL NEW REQUIREMENTS DETER VOTERS?

Advocates for minority communities argue that even minimal identification requirements can disenfranchise eligible voters, because people of color and immigrants are more often subjected to requests for identification, either properly or improperly.

In the February Special Election in Nassau County to fill a vacant State Senate seat, voting rights groups became alarmed that there might be widespread voter intimidation at the polls because of comments by Joseph Mondello, the Republican Party Chairman for New York State and Nassau County. "Our poll watchers and election inspectors will challenge people to show some kind of identification as to who they are," Mondello reportedly said. "They have a right to ask for identification to make sure you are John Smith. Our people have been cavalier about this in the past. This time, in this election, we're dearly concerned."

According to the Asian American Legal Defense Fund, overzealous poll workers have been improperly implementing identification requirements at voting places in recent elections, and minority voters and voters with limited English are the groups most often asked for identification when it is not actually required.

Research also suggests that Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans are less likely to vote when required to show identification than when they simply have to state their names.

THE NEED FOR VOTER EDUCATION

To avoid confusion at the polls and the disenfranchisement of voters, election reform advocates have argued for years that New York City, with such a large and diverse population, has to be sensitive to a wide array of voter needs that other localities might not need to consider.

City residents, for example, are less likely to drive or own a car than their suburban and rural counterparts, and therefore are less likely to hold a driver's license.

The personal and cultural experiences of many of New York City's immigrants, some argue, should be taken into consideration. For instance, a significant portion of New York's immigrants come from oppressive regimes where identification cards were used by authorities as a form of intimidation.

Members of these communities may be less likely to carry identification, or to provide it on demand, especially if it is not legally required.

Unfortunately many voters are unaware of their rights. And so some voters who are asked to show identification may simply decide to leave the polling station and not return. While New York may not have the strict identification requirements that other states have, some experts fear that the misuse of HAVA identification requirements, especially when it results in the disenfranchisement of a voter, could damage long and short term voter participation among minority and non-English speaking voters.

The New York City Board of Elections has been urged to increase poll worker training and voter education, to ensure that poll workers and voters are aware of the HAVA requirements and their rights. With the eventual introduction of new voting machines and processes, poll workers will be asked to perform more services for voters and voters will be less familiar with the process.

In the coming years, overall training and education will become more important for the Boards of Elections. Election reform advocates, civic groups and community organizations will be asked to play a significant role in educating voters as well.

Doug Israel is director of public policy and advocacy for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Andrea Senteno is program associate.

Â

New Bills: Housing Repairs and a Street Fight

City Council members on April 12 introduced two bills that would create a system to provide more rigorous inspection and more extensive repairs for buildings with flagrant housing violations. Council members took advantage of the meeting to denounce controversial radio host Don Imus, but at the same time, they ignited a furor of their own when a routine bill to change the names of a number of city streets included an avenue named after activist Sonny Carson.

Safer Housing

The two housing bills would increase the city's power to inspect and repair neglected buildings at the landlords' expense.

Intro 560, introduced by Councilmembers Vincent Gentile, Melinda Katz and Erik Dilan, would help city inspectors gain access to buildings with violations. According to Eric Kuo of Councilmember Vincent Gentile's office, housing inspectors currently lack clear guidelines to gain access to buildings when property owners refuse to let them in. The bill sets forth a procedure for inspectors to document their unsuccessful visits and secure warrants from the court.

Under the proposed Safe Housing Act (Intro 561), introduced by Councilmembers Letitia James, Gale Brewer and Erik Dilan, and Speaker Christine Quinn, the city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development would force repairs of residential buildings with the most egregious safety violations. The city currently has the power to make emergency repairs, but Kate Suisman, James' chief of staff, explained that these repairs are not applied systematically and often only address immediate problems, such as a leaking pipe. Additionally, landlords avoid completing repairs and sometimes have to be taken to court.

Ray Brescia of the Urban Justice Center said of the current difficulties in enforcing housing safety, "More than half the battle is to first get HPD interested in a building." In addition to activating enforcement of the city's worst buildings, the bill would compel landlords to carry out repairs.

With the act's increased authority, the city would target 200 buildings a year for rigorous inspections and "top to bottom" repairs - for instance, beyond fixing a leak, the city could require new pipes throughout the structure.

Under the proposed law, if a landlord refuses to comply with required building work within four months, the city would complete the repairs and charge the owner. According to Housing Commissioner Shaun Donovan, the program would cost $10 million a year, some of which would be recovered from landlords and building liens.

Many New York City buildings chronically fall into hazardous conditions. Repeat violations are common with 46 percent of the 10,000 buildings that received emergency repairs in 2006 also having received them in 2005, and 22 percent having such repairs in 2004 too.

Opportunistic landlords may prefer to neglect rent stabilized units until the tenants leave rather than make the repairs, a trend which Councilmember James summarizes as "displacement by neglect."

With the number of building violations increasing and the demand for affordable housing in the city remaining high, the program seeks to protect vulnerable tenants and to maintain the condition of affordable housing.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the New York Immigrant Coalition, property owners and agents all support the measures. Frank Ricci of the Rent Stabilization Association said, the bills would help "target the really irresponsible owners … who give everyone else a bad name."

Street Naming Controversy

Sonny Abubadika Carson Avenue was one of 53 lanes, ways, corners, plazas and other streets to be renamed in Into 556, Council Speaker Christine Quinn conceded that the council's fondness for renaming streets is often ridiculed, but she urged her fellow members to separate out the consideration of the Carson renaming because of his anti-white statements and "divisiveness."

Sonny Carson, who died in 2003, was a Korean War veteran and active in several Brooklyn movements including the Republic of New Afrika, the African Burial Ground project, securing voting rights for ex-prisoners, the Black Men's Movement Against Crack, protests of police brutality and boycotts of Korean groceries. He also helped to establish Medgar Evers College. Councilmember Councilman Al Vann, who proposed the name change at the recommendation of the local communyt board, cited Carson's civic work in Bedford-Stuyvesant as grounds for the honor.

A recent New York Post editorial agreed with Quinn. And the divisiveness over Carson Avenue was evident at a meeting of the Council parks committee last week as members voted along racial lines to remove the name from the bill. Several protestors were removed from the meeting room.

Though Carson's name will not grace an honorary avenue, at least for the time being, Jerry Orbach Way named for the Broadway and Law & Order star will make the cut after a few setbacks during the community board recommendations process earlier this year.

Councilmember Charles Barron stated that if Carson Avenue were removed from the bill package, he would demand to know the background of all individuals who have street names proposed for them.

Defacement of Religious Items

Also at the meeting, Councilmembers Vincent Gentile and Peter Vallone introduced a bill to protect religious items and displays on private property. Intro 559 would extend the law against damaging houses of religious worship and their contents to private property. Under the proposed bill, such a crime would constitute a misdemeanor and carry punishments of imprisonment for up to a year or a fine between $500 and $2,500, as well as possible civil penalties. In neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst in Gentile's district, numerous religious displays outside of people's homes have been defaced.

Councilmember Vallone also introduced a bill to institute criminal penalties for public lewdness.

Councilmember James was planning to introduce a resolution calling for the firing of Don Imus at the next council meeting, but now that CBS has already dismissed him, the resolution will likely be tabled or modified.

Other Bills

Resolution allowing council to sign onto amicus brief

Resolution calling for new zoning considerations of small single family homes

Â

Jittery Wall Street, Calm City?

The 400-point drop in the Dow Jones average on February 27 was the biggest Wall Street decline in nearly four years. It capped a day of international stock market jitters that began with steep declines in Hong Kong and Shanghai and then traveled around the world. With New York's economy so dependent on finance, many city residents understandably fear any signs of weakness on Wall Street.

So is there reason to be concerned? If Wall Street sneezes, will New York catch pneumonia? Many parts of the economy continue to be robust, with jobs and wages growing, although they still remain below the peak levels of the 1990s. Such overall data and the trends for specific parts of the local economy suggest that New York City’s economy may slow but it won’t turn down unless Wall Street settles into a sustained slump.

READING THE SIGNS

â€Driving’ The EconomyMany economists use the concept of “drivers” to refer to sources of economic stimulus or to the sectors that heavily influence the economy’s course. For example, consumer spending is often referred to as the main factor influencing the magnitude of growth in the national economy. In New York City, Wall Street, tourism, professional services, information (media), and real estate/construction, are often considered the main “drivers” of the regional economy. With the exception of real estate/construction, these “drivers” are also “export” sectors that cater to a national or international market and serve to bring spending and incomes into local economy. The real estate/construction sector serves this purpose indirectly. |

Some experts see indications that the economy could stumble in the coming months. Former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan believes there is a one-third chance of recession before the end of this year. Greenspan reasons that the economic expansion is starting to totter a bit in its old age and that a worsening slump in the real estate market could knock it off-kilter enough to trigger a recession.

The bursting of the housing "bubble" is widely acknowledged as the economy's biggest trouble spot. Housing prices and sales have fallen sharply in many areas, although not in New York City, and the low mortgage rates that fueled the housing frenzy are history. Home mortgage delinquencies and defaults have reached record levels. Many "subprime" lenders, the finance companies that specialize in granting mortgages to people with weak credit records, are in serious trouble. In a manner reminiscent of the savings-and-loan crisis of 20 years ago, we are beginning to pay the price for the financing practices that drove the current real estate boom.

Pessimists point to other signs of economic weakness, as well: slowing job growth, a declining manufacturing sector, weak business investment, record trade deficits and rising labor costs. Like Greenspan, they conclude that the U.S. economy is slowing further and could tip into recession. (While there is no single set of criteria defining a recession, it is often considered to be a period of two quarters of declining economic activity or output.)

But other economists point to different indicators and draw a happier conclusion. Citing low unemployment, rising wages, rising bank deposits, low inflation-adjusted interest rates, and a relatively strong global economy, these observers expect continued growth. The optimists do not believe sub-prime lending problems will spread, and they tend to see the manufacturing slump as an opportunity to shift capital and labor to sectors with brighter growth prospects.

Both pessimists and optimists will agree, though, that economic forecasting is tricky. A recent Wall Street Journal poll of 60 economic forecasters predicted, on average, a 25 percent chance of recession over the next 12 months. Testifying before Congress recently, current Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said he expected a continuation of “moderate” growth, but emphasized that the Fed needed to be “flexible given the uncertainty we face.”

THE LOCAL PICTURE

How does any of this play out for the New York economy? Certainly, New York is touched by all of these forces to some extent. On balance, however, it appears that New York City is better positioned than much of the U.S. economy. Many "drivers" of the regional economy continue strong. [See box.]

Real Estate

Despite the slump in many parts of the country, the local real estate market remains robust. Housing prices generally have held up, easing slightly in some neighborhoods while continuing to rise in others. While most renters and prospective home buyers without millions to spend have a hard time affording a decent place to live, the luxury residential market continues to flourish, boosted most recently by record Wall Street bonuses.

Meanwhile, the market for office space in Manhattan is soaring. Stephen Ross, a major New York real estate developer and chair of the Real Estate Board of New York, recently claimed that the condition of the commercial real estate market here couldn't "get any better". The average rent in Manhattan hit $53 a square foot in the first three months of 2007, an all time high, according to the brokerage firm Cushman Wakefield.

However, mortgage foreclosures in New York City jumped 18 percent in the last half of 2006, and an alarming number of low- and moderate-income families are at risk of losing their homes. The Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project estimates that 15,000 homeowners will face foreclosure this year, with the biggest impact coming in predominantly minority neighborhoods like South Jamaica and Cambria Heights in Queens, Bedford-Stuyvesant and East New York in Brooklyn, and Williamsbridge in the Bronx.

Construction

With several large public transportation projects and various publicly subsidized building projects starting to get underway, the outlook for New York City construction activity is brighter than it has been since the 1960s. For construction, the greater worry is the rising cost of materials and the possibility of capacity constraints.

Tourism

Record levels of tourists have kept most hotels fairly full for the past three years. New construction will add an estimated 5,000 hotel rooms to the city in 2007, largely offsetting the number lost to luxury condo conversions over the last three years. The white tablecloth restaurant industry has been amply fed by higher tourist spending, as well as by rapid high-income growth.

Finance

Although New York's financial sector still provides several thousand fewer jobs than it did at its peak in 2000, Wall Street profits have grown impressively in recent years (the top five firms had combined profits of over $30 billion last year) and compensation packages are as generous as ever. This winter's bonus season saw a record $24 billion paid out on Wall Street, according to estimates by the State Comptroller's office.

The city's economic horizon is not without a few clouds. The most worrisome is probably the vulnerability of certain Wall Street firms that lent heavily to sub-prime lenders. The Economist magazine recently warned that the profit growth of financial powerhouses linked to sub-prime lenders "looks set to fall."

THE JOB PICTURE

Wall Street may have a hugely disproportionate effect on the New York economy, but like the Yankees, it is not the only game in town.

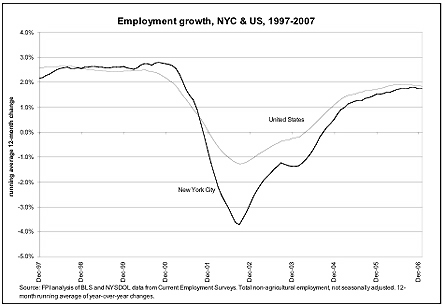

The number of private sector jobs in New York grew at a fairly strong 1.8 percent annual rate for the last three years. For the past several months, the city’s job growth has nearly matched that of the U.S. economy overall. Although this relatively robust job growth still leaves the city with about 50,000 fewer jobs than it had in December 2000, New York City’s job growth accounts for a disproportionate share of the state’s job growth during the recovery. The city’s solid job growth coupled with weak growth in most of the rest of the state means that jobs have been growing in the city at a pace three times that of the balance of New York State over the past three years.

Five industries each had employment growth of five percent or better in 2006. In order of most jobs gained, these were professional services, securities, home health care, construction, and banking. Together they accounted for much of the city’s total job gain. Within professional services, advertising and accounting employment grew by double digits.

With the exception of banking, these industries are also among the overall leaders in job growth since 2003. Other industries accounting for the city’s job growth during the recovery include (in order of most jobs added): retail trade, restaurants, social services, private educational services, civic and religious organizations, real estate, and doctor’s offices. For retail trade and real estate, job growth was fastest in 2004, the first full year of recovery, but has slowed since then.

Similarly, other sectors have their own dynamics and face broad trends that need to be understood in taking the economy’s pulse.

Take healthcare for example. Employment in home healthcare services has expanded by 40 percent since mid-2003, and jobs in doctors’ offices and outpatient care centers have increased by 10 percent. On the other hand, while hospitals and nursing homes together employ over 200,000 workers in New York City, there has not been any net gain in institutional employment over the past three-and-a-half years.

The broader leisure and hospitality sector, which encompasses hotels, restaurants and the arts, has been a steady contributor to recovery job gains. Both performing arts and restaurants have increased jobs by 13 percent since mid-2003. But the net employment level in hotels has risen by less than five percent because the conversion of hotels to condominiums. The recent boomlet in hotel construction should again boost the hotel workforce.

And not all parts of the economy have thrived. Manufacturing and telecommunications are the only major sectors to have lost jobs during the city’s recovery. Since mid-2003, both have lost about one-sixth of their employment bases, with manufacturing losing 20,700 jobs while a net of 4,100 telecommunications jobs have disappeared (the loss of jobs in wired telecom has far exceeded the growth in wireless telecom). Employment in both manufacturing and telecommunications is off by about 40 percent since 2000.

Telecommunications is part of the broader information sector that includes modestly sized, but high profile industries such as publishing, motion picture production, and broadcasting. These industries have seen only slight job growth, ranging from one to three percent, since mid-2003.

WHAT THE NUMBERS MAY MISS

Economists are beginning to note that the State Labor Department payroll jobs data may be missing an important part of the story: the rise in the self-employed. Indications are that the number of self-employed people and workers considered “independent contractors” are increasing at a faster rate than the number of people on a payroll. Many businesses are hiring people as free-lancers or consultants and not calling them “employees.” Businesses that treat workers as “independent contractors” do not make payments for payroll taxes or social insurance premiums. It is hard to pinpoint how much of New York City’s job growth is in the form of “self-employment” or “independent contractors,” but state-level data indicate that there was an increase of over 200,000 in this category between 2000 and 2004. During this same period, the net decline in payroll jobs was close to 200,000.

THE WAGE PICTURE

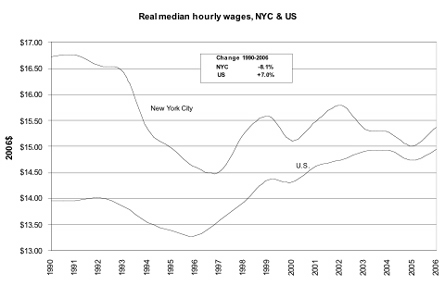

Last year saw the first real gain in wages in New York City since 2002. This is based on the median hourly wage derived from the monthly Census Bureau survey of households. If all wages are ranked from lowest to highest, the median is that wage at the mid-point in the distribution. To look at wage changes over time, economists usually adjust the survey data for inflation and look at the trend in “real” wages. In 2006, New York City saw a 2.4 percent increase in the real median hourly wage. Although the median wage had increased fairly steadily through the late 1990s to 2002, when adjusted for inflation, the real value of the median wage was still lower in 2006 than it was in the early 1990s.

A continued growth in the median wage could help sustain economic growth in New York City in the face of possible turbulence at the national level. Despite the good news on wages and in many parts of the economy, the biggest risk to the New York City economic health remains a downturn on Wall Street. For now, though, that is only a possibility and not a probability. And many other parts of the economy should continue to generate jobs and economic stimulus – even if the stock market gets the jitters.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist for the Fiscal Policy Institute.

Â

Stated Meeting -- Protecting

The City Council last week passed a bill that would protect "educational whistleblowers", setting up another conflict with Mayor Michael Bloomberg just two weeks after he rejected its plan to regulate pedicabs.

At its stated meeting, the council also passed laws that would extend benefits for family members of city workers who die in the line of duty, toughen prohibitions on video piracy, and protect the privacy of lobbyists' families.

EDUCATIONAL WHISTLEBLOWERS

The council whistleblower bill would extend protections to teachers, social workers, and others who report conduct that negatively affects a child's welfare.

Speaker Christine Quinn argued that there are holes in the current whistleblowers law that could leave some teachers unprotected from retaliation. She said that she was not aware of any case where a teacher had been punished for speaking out, but argued, "There is certainly evidence of teachers who have indicated that they have not come forward, because they feared what would happen."

Some outside the council charged that the bill as intentionally providing vague protections it as a way for critics – namely the teachers union – to snipe at the mayor's changes to the educational system.

The Daily News argued that state legislation already protects teachers who report mismanagement or abuse of authority, and said the law is "designed to sabotage, at the behest of the teachers union, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein's driver to bring accountability to the city's classrooms."

The United Federation of Teachers tried unsuccessfully to get a similar provision written into its contract last fall, said Bloomberg. He says he will veto the bill.

The bill passed by a vote of 43 to one, with Peter Vallone Jr. voting no, giving the council enough votes to override the veto.

FILM PIRACY

To protect the film industry, the council passed legislation (Intro 383) intended to cut down on film piracy. Over the last several years, city officials have taken steps to encourage the city's film industry, such as the creation of a film industry tax credit. As a result the industry is thriving, according to the council report that claims that the tax credit alone has generated 6,000 jobs and increased spending on film production by $450 million.

The illegal film industry also flourishes in the city, however. Between June 2004 and June 2005, 800,000 counterfeit DVDs and 700 DVD burners were seized in New York City.

Almost all bootleg movies are made by simply taping the screen in a movie theater, according to NBC-Universal, and half of these recordings are made in the New York area. This bill would make it illegal to operate film recording equipment in a movie theater, and violators would face six months in jail and fines of up to $5,000. It passed unanimously.

INCREASED BENEFITS FOR FAMILIES OF CITY WORKERS

Families of corrections and sanitation employees killed in the line of duty would continue to receive health benefits under another bill (499-a) passed by a unanimous vote, a benefit already extended to the families of police officers and firefighters.

The families of corrections and sanitation employees who are killed generally receive these benefits already, but the council has to amend the administrative code for each individual case. This bill would make that step unnecessary.

The families of two sanitation workers would benefit immediately, according to Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, the bill's primary sponsor.

Addabbo has previously introduced similar legislation that would apply to all city workers, but the idea languished due to concerns about the cost. He says he hopes to reach that goal "piece by piece," by protecting classes of city workers who are at the highest risk first.

LOBBYING AND PRIVACY

The council amended its recent changes to the lobbying laws, responding to concerns that the requirement that the addresses of lobbyists' children be published could endanger their safety. Watchdog groups consider information about donations from lobbyists' families essential, because these donation can serve as a way around contribution caps.

The change would not ease disclosure requirements, said Quinn; it would simply keep certain information private.

"You and the public will know that their child gave," she said in response to a reporter's question. "You won't know their child's address."

RESOLUTIONS: AMICUS BRIEFS AND LIBRARY WEEK

The council also passed two resolutions.

One (Res 803) would allow Quinn to file an amicus brief in the council's name in a lawsuit regarding a dispute over whether a landlord is allowed to receive city tax abatements while refusing to accept section-8 vouchers. Quinn believes that the landlord must accept the vouchers given to low-income residents to use for housing costs, and the Bloomberg administration agrees.

The three Republicans – Dennis Gallagher, Vincent Ignizio, and James Oddo – voted against the resolution.

The second resolution (Res 746), designated the week of April 15 to April 21 as "Library Week." It passed unanimously.

Â

A "Customer" Survey for the City

Is access to public transportation New York’s most important municipal service? Is the city’s poorest performance in the area of re-entry programs for former convicts? Is the public school system still faltering?

Yes, yes, and yes, a group of community leaders from the five boroughs told Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum at a forum on citizen satisfaction with municipal services. While these respondents are hardly a cross section of all New Yorkers, their comments on city services indicate what public officials might learn if they were to ask city residents Mayor Ed Koch’s signature question, “How’m I doin’?”

Who is the best judge of how well city government performs -- the bureaucracy responsible for providing service or the citizens who are supposed to benefit from municipal programs? Many experts agree that citizens are as qualified to evaluate city services than government itself, if not more. “The best way to encourage government performance is to measure it, and the best indicator of government performance is citizen satisfaction,” says the International City and County Management Association.

Still, in New York, most standard measures focus on government’s own definitions of success. The city measures how much money and staff time are put to use addressing problems, as well as the number and scope of new programs launched in response. It looks far less frequently at the actual results of programs or residents’ experiences with and attitudes toward those programs. While the Bloomberg administration has made great strides in performance assessment and reporting, New York City still does not regularly and systematically survey its residents’ perceptions and assessments of the services they receive.

Still, in New York, most standard measures focus on government’s own definitions of success. The city measures how much money and staff time are put to use addressing problems, as well as the number and scope of new programs launched in response. It looks far less frequently at the actual results of programs or residents’ experiences with and attitudes toward those programs. While the Bloomberg administration has made great strides in performance assessment and reporting, New York City still does not regularly and systematically survey its residents’ perceptions and assessments of the services they receive.

For example, the city knows that the number of calls to the 311 emergency hotline continues to rise. It also knows how quickly the calls were answered. But the government does not have information on how many of the 40 million callers to 311 have been satisfied with the city’s response to their problem, nor does it have information on how New Yorkers who do not call 311 feel about government services.

SURVEYING THE CITIZENS

Hundreds of U.S. municipalities, among them Phoenix, Miami-Dade County, Detroit, San Diego, San Jose, Austin, and Portland, Oregon use resident surveys. Gregg Van Ryzin, a scholar who follows municipal measurement trends closely, notes that the Government Accounting Standards Board, the International County Management Association and the National Academy of Public Administration have all championed customer surveys as an index of local government performance. Locally, a February 2002 “Policy Brief” by the New York City Independent Budget Office recommended that the city “identify and report on results that matter to the public and reflect the way the public sees and uses city services.” The office observed that “public accountability requires, in part, viewing an agency from the citizens’ perspective, understanding their expectations and collecting information that helps the public assess how well government is meeting those expectations.”

But effective, accurate and policy-relevant surveys are not easy to conduct. The challenge in New York is particularly daunting because of the sheer size of the city and the difficulty of distinguishing borough and neighborhood problems from those affecting the entire city. Surveys are expensive to design and write. Those drafting the survey must work to frame questions that reflect the public concerns – and not the thinking of whoever is writing the questions. A good survey must be tested before the final version is released into the field, and a statistically representative sample of respondents must be selected.

DESIGNING A SURVEY FOR NEW YORKERS

Despite such obstacles, New Yorkers may soon have a chance to grade their government. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum has begun an ambitious new program to gauge resident satisfaction. Working with experts from the Baruch College's School of Public Affairs, (including the two of us), she has assembled a Civic Leader Board to develop a questionnaire that will ultimately be circulated among a broadly representative sample of New Yorkers. Dubbed the Public Advocacy Project, the program will provide both an ongoing forum for community leaders and a regular gauge of residents’ satisfaction with key government services.

Despite such obstacles, New Yorkers may soon have a chance to grade their government. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum has begun an ambitious new program to gauge resident satisfaction. Working with experts from the Baruch College's School of Public Affairs, (including the two of us), she has assembled a Civic Leader Board to develop a questionnaire that will ultimately be circulated among a broadly representative sample of New Yorkers. Dubbed the Public Advocacy Project, the program will provide both an ongoing forum for community leaders and a regular gauge of residents’ satisfaction with key government services.

Late last year, more than 60 civic leaders came to Baruch College to rate city services and to help provide topics for a future survey. Drawn from community organizations throughout the five boroughs, each leader brought a different perspective to the conversation. The structure was similar to the one employed in the summer of 2002 in the Civic Alliance’s “Listening to the City” program, in which thousands of New Yorkers gathered to express their views on the rebuilding of lower Manhattan after the 9/11 attacks.

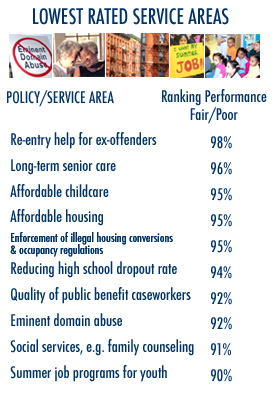

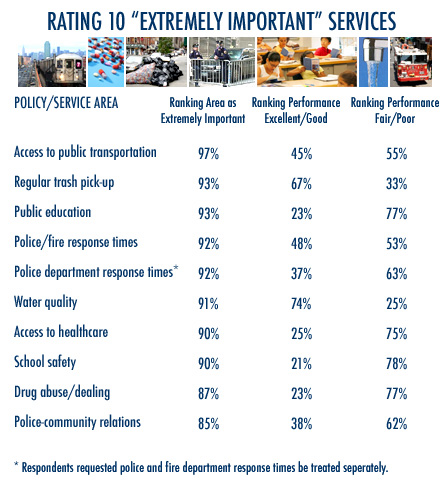

At the forum, community leaders rated 100 city services as “extremely” “very” “somewhat” or “not that” important and on whether the service provided is “excellent,” “good,” “only fair” or “poor.” Each participant was provided with a handheld voting device. While voting was anonymous, the results of every vote were immediately visible on screen, providing immediate feedback for the participants. Within two hours, we had one roster of the services participants deemed most important, and another rating the city’s performance in each area (see tables).

There was remarkable agreement on the top 10 service areas, with each being cited by at least 85 percent of the respondents. Access to public transportation ranked first, closely followed by regular trash pick up and public education.

Five focus groups then discussed the 10 areas in which city services were perceived to be most in need of repair. Along with helping former prisoners re-enter society, the groups cited long-term senior care, affordable childcare and affordable housing as needing improvement. For each topic, the groups provided a detailed breakdown of the problem; a sense of the city responses to those problems; positive elements of the city’s response; references to other responders, such as nonprofit organizations that have a good reputation for service/response in the area; and illustrations of the problem in specific neighborhoods.

Participants then came back into plenary session to hear what happened in the groups and to talk about next steps. They also had an opportunity to hear from the public advocate and to provide her with their reactions to the process.

LEARNING FROM COMMUNITY LEADERS

While the session provided valuable information about what some of New York’s most active citizens think of city services, the discussion’s core purpose was to generate and focus questions for a telephone survey of the general population. Telephone surveys cannot cover the full range of issues facing residents because they simply take too long to administer. It took a very dedicated, knowledgeable group of respondents two hours to move very quickly through our 100 topics; most surveys have to be completed within less than 25 minutes to maintain participation. By soliciting input from community leaders, we were able to identify issues that we had not thought about ourselves and frame follow-up questions around problems identified by the leaders, not by scholars or government officials.

We found several things that we had not expected. For example, the initial list of 100 topics had an item on “police/fire department response times.” The community leaders insisted that those two categories be separated on the public survey given their strong sense that police response times were inadequate, “particularly on weekends.” That concern emerged as one of the 10 most important issues facing the city.

Large categories, like “crime” need to be broken into smaller pieces to get a clearer idea of how to improve city services. For example, “safety from violent crime” was only 24th on the “extremely important” list, but three crime-related categories ranked in the top 10: police response times (fifth), drug abuse and drug dealing (ninth) and police-community relations (tenth). The discussion with community leaders will prompt an expanded treatment of crime in the broader survey.

We found several benefits to involving community leaders in the design of the survey. First, it creates a forum for civic leaders to express their opinions to public officials. Second, it enhances those leaders’ roles as advocates, strengthening community organizations and improving their ability to speak on behalf of the residents they serve. Third, the rich detail and extensive examples elicited in the focus groups provided a wealth of material for inclusion on surveys and illustrative stories about the way that residents live with problems and the city’s efforts to solve them. For example, one discussant said of police response times, “They’re fine Monday through Friday, but terrible on the weekends.” Many people talked about a lack of information -- on school bus schedules, on sanitation schedules, on street repair, and other vital services. These specific cases will help sharpen questions for the survey.

The final version of the survey will be fielded via telephone to a representative sample of New Yorkers in the fall of 2007. The findings will be circulated widely, discussed in depth with the community leaders, and repeated, with emphases on different issues, as the survey evolves in subsequent years.

These citizen surveys will provide a robust set of data with which to approach elected officials and the leaders of city agencies. It will offer an important corrective to the “complaints-only” data available from 311 and move New York closer to a genuine measure of service outcomes. City officials will finally know – from New Yorkers themselves – how they’re doin’.

Â

Broadband Haves and Have Nots

The last week of March saw two seemingly unrelated events that could affect the lives of poor people in New York City.

In one Mayor Michael Bloomberg outlined his plans for "Opportunity NYC,"which will provide cash incentives to low-income parents who make sure their children go to school, take their children to the doctor regularly and seek opportunities for employment and job training. The mayor hopes that such incentives will break the “cycle of poverty” that still traps many city families.

The second took place in the Bronx, where an advisory committee on expanding access to high-speed Internet access in New York City held its first hearing.

Bloomberg has stated repeatedly that tackling entrenched poverty is a core priority of his second and final term. His new opportunity program is a way to do that. And the mayor wants to increase Internet penetration throughout the city and the availability of “broadband” (high speed, wired or wireless access) connections. In this area, though, Bloomberg’s focus is on improving broadband access for the city’s businesses, especially those outside Manhattan. There is no doubt that this is critical; a recent report by the United States Department of Commerce documents economic benefits for communities that expand the level of broadband access

But the mayor has been less aggressive in trying to increase Internet access in disadvantaged communities. And many experts see changing that as one way to help reduce poverty on the harsh side of the digital divide. With improved access to high-speed Internet capabilities, children would enjoy enhanced educational opportunities and their parents could learn the skills necessary to thrive in an increasingly computer-based economy

THE NEW DIGITAL DIVIDE

Although broadband has become increasingly available for people of modest incomes, it has not reached those living at the lower end of the income scale. According to the most recent report by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, only 21 percent of households with an annual income of $30,000 or less had a broadband connection at home in 2006. On the other hand, 68 percent of households that earn over $75,000 had a home broadband connection.

While most businesses in Manhattan have a variety of options for high sped Internet options, businesses in the other four boroughs and residents all around the city are not so favored, according to a briefing paper prepared for the Bronx hearing. “Many of the businesses around the five boroughs have limited options for obtaining broadband and often find it impossible to access a reliable high-speed connection at all,” the paper said. And it continued, “Most residents have only one or two service providers from which to choose, and many are unable to afford the service.”

“Here in New York City, many underserved communities won't survive in this new information age without the technical knowledge many of us take for granted,” Council Speaker Christine Quinn said in a written statement before the hearing. “The bottom line is we need to use out-of-the box-thinking to ensure that today's technology is used to improve the future of New Yorkers.”

Improving access to broadband – and developing new ways to use it – could create jobs, improve schools and make the city safer, Gale Brewer, chair of the City Council technology committee, has said.

EXPANDING ACCESS

Many other American cities — from Philadelphia to Chicago to Houston to Los Angeles — have launched initiatives to increase broadband access for residents and visitors, as well as businesses. Meanwhile, New York has made modest enhancements to providing wireless (not necessarily broadband access) in city parks.

In an effort to expand broadband access for New Yorkers, City Council in 2005 passed Local Law 126, sponsored by Brewer, which established a “temporary advisory committee” to offer guidance to the mayor and City Council Speaker on “issues pertaining to access to broadband technologies within the city of New York” PDF). The City Council speaker would appoint seven members of the committee; the mayor would appoint eight. It was this committee that sponsored the Bronx hearing.

Four more such sessions, one in each borough, will be held this year. The goal for each hearing is to ascertain what New Yorkers believe is an “affordable” price for broadband access; how New Yorkers who already enjoy broadband use it; and how those without broadband access would use it if it were available to them.

The members of the Broadband Advisory Committee selected by the Council Speaker reflect Brewer’s belief in public investment to increase broadband access. They include Andrew Rasiej, who ran for public advocate in 2005 on a platform of radically increasing wireless access throughout New York City, and Neil Pariser, senior vice president of the South Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation, which has worked to close the digital divide in its corner of the City.

The mayoral appointees reflect a more business-centric approach to the issue. They include Howard Szarfarc, president of Time Warner Cable of New York and New Jersey, and Thomas Dunne, a vice president of Verizon New York. Szarfarc and Dunne also serve on the Mayor’s Telecommunications Policy Advisory Group and were among the people who in 2005 developed the mayor’s current telecommunications policy agenda, “Telecommunications and Economic Policy in New City: A Plan for Action.” With its clear focus on the business sector, this agenda does not address how to increase broadband access in disadvantaged communities.

Of course it makes sense to have business representation on the Broadband Advisory Committee. Unfortunately, this committee contains two groups that are working at cross-purposes. One side seeks government action to bridge the digital divide, while the other believes in an entrepreneurial approach.

It remains to be seen how much impact the Broadband Advisory Committee will have on public policy. Whatever happens, there is a strong case to be made for government investment to expand broadband access in poor communities. Even if “Opportunity NYC” succeeds beyond all expectations, a cash transfer program can only be so effective in a labor market that requires everyone to be comfortable with computer technology

Â

Stated Meeting -- Maintaining Mitchell- Lama

The City Council passed bills intended to keep affordable housing available, and to protect the safety of construction workers at its most recent stated meeting on March 28, 2007. It also approved its budget for the upcoming fiscal year.

All of the bills were passed unanimously by a vote of 47 to 0.

MITCHELL-LAMA HOUSING

The council passed two designed to keep property owners from opting out of the Mitchell-Lama, a tax incentive plan that one housing activist has called "the best housing program any government anywhere has ever designed."

The Mitchell-Lama program was started in 1955, offering developers low-interest mortgages and tax breaks in exchange for guarantees that their apartments would be accessible to middle class families. The most famous example of this housing is Co-op City in the Bronx, which has 15,000 apartments.

Developers who accepted the tax breaks are allowed to opt out of their commitments to middle class housing in 20 years. Increasingly, they are doing so, drawn by the potential for huge profits in the city's tight real estate market.

The bills introduced into the council at the behest of the mayor would make certain types of co-ops and condos eligible for additional tax breaks in exchange for guarantees that they would stay in the Mitchell-Lama program for 15 years.

Intro 203 would extend certain tax credits (known as the J-51 tax benefit program) to Mitchell-Lama participants even if their buildings receive subsidies for alterations or improvements. Such buildings are not eligible for the benefits currently. Intro 204 would offer the same tax benefits to co-ops and condos that are currently too expensive to qualify. In exchange for these tax incentives, participants would have to must agree to stay in the Mitchell-Lama program for 15 years.

Council Speaker Christine Quinn said that the council had not developed a price estimate for the measure, largely because the council cannot predict how many property owners will decide to take the deal.

SCAFFOLDING SAFETY

The council also passed several bills that came from Mayor Michael Bloomberg's scaffolding safety task force.

Seventeen construction workers fell to their deaths last year, up from nine the year before. As a result, Bloomberg formed a task force to establish tougher regulations for hanging scaffolding. As part of the task force's recommendations, Councilmember Erik Dilan – himself a member of the panel – introduced three bills.

The bills would require construction firms to notify the buildings department when they plan to use C-Hook scaffolding, the type of hanging scaffolding involved in over half of the scaffolding deaths in 2006 (Intro 523). The other bills would also increase fines for violators (Intro 524), and require daily written inspections of scaffolding by site supervisors (Intro 522).

The council approved all three bills on March 28 by a unanimous vote of 47 to 0. The mayor has already endorsed them, but must sign them before they become law.

INTERNAL COUNCIL BUDGET

The council also passed its annual operating budget (Res 787). This budget, which the council submits to the mayor for approval every March, is the total amount of money that the council allocates itself to operate.

The total budget is $54.6 million, a 7.5 percent increase from last year. Most of this rise in spending is non-discretionary, according to Speaker Christine Quinn, and is due to higher salaries for council members, cost-of-living pay increases for council staff, rent increases for council offices in 250 Broadway, and an upgrade of the council's information technology capabilities.

Â

Auxiliary Officers Assistance Plan

This plan has been proposed by City Councilmember David Weprin.

Equipping Auxiliary Officers With:

1. Bulletproof Vests

2. Mace

3. Expandable nightsticks

4. Protective masks

5. Automatic External Defibrillators for all APSU (Rescue) Units who are already authorized by the NYPD for its use.

Legislation Calling For:

6. Increased penalties for attacking and/or injuring Auxiliary Police Officers. By granting Auxiliary Officers the status of PEACE OFFICER WHILE ON DUTY, Auxiliary Members will be re-qualified as "NYC SPECIAL PATROLMEN." a status that exists in the NYC Administrative Code and the NYS Criminal Procedure Law. The change in status will automatically bring with it an increased range of penalties for injury to an Auxiliary Officer.

7. Appropriate benefits for disabled Auxiliary Officers and their families.

8. Mandated regular reporting by NYPD to City Council on Auxiliary Program statistics such as equipment, vehicles, training, hours, and number of personnel.

9. Improved and increased training and self defense classes for Auxiliary Officers to be administered by Police Academy Instructors.

10. Full Restoration of Auxiliary Emergency Service Unit (AESU) name and function in order to allow Auxiliary Officers to properly serve as the auxiliary arm/adjunct of the NYPD Emergencies Services Unit as was originally mandated upon its creation in 1950.

Â

Voting, Yes. Democracy, Maybe.

|

|

|

|

For More on the Special Elections:

• Staten Island’s North Shore • Staten’s Island South Shore • Central Brooklyn |

In special elections, held March 27, Demcrat Matthew Titone won the seat from Staten Island's North Shore and Republican Louis Tobacco won the seat from the South Shore.Democrat Micah Kellner is all set to go to Albany to represent residents of Manhattan’s East Side and Roosevelt Island in the New York State Assembly. He has won a raft of endorsements in his quest for the Democratic nomination, discouraged various rivals from running and, because of an overwhelming Democratic edge in the area, seems poised to defeat his Republican rival handily, whoever that might be. “It appears the race has already been decided,” said Susan Chamlin (in pdf format), one of several candidates who dropped out of the contest in the face of Kellner’s support from key party officials.

There is one problem: The seat Kellner hopes to occupy is still occupied, and no election is scheduled. Governor Eliot Spitzer has nominated the current incumbent, Alexander “Pete” Grannis, to be his environmental conservation commission, but the Republican-controlled State Senate has not confirmed him.

Whatever one thinks of Kellner, his anointment by party leaders again raises questions about the system of special elections for filling vacancies in New York State and city. While there is no special election scheduled for Manhattan, this Tuesday there will be special elections on Staten Island to fill two vacancies in the State Assembly. And next month, residents of the 40th City Council District in Brooklyn will vote once again – for the third time in less than six months – in a redo of a February special election whose results were voided when it became known that the winner, Mathieu Eugene, may not have met the legal requirement for residency in the district.

All this voting might appear to be a heady dose of democracy. But how much choice do voters in special elections really have?

In most of them, few eligible voters even know that the election is taking place. After all, who votes in March? A February State Senate contest in Nassau County attracted a huge amount of attention, including appearances by Governor Eliot Spitzer and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and a record $3.5 million in campaign spending. Even so, only 25 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, compared to 41 percent who voted in the same district in November.

In the legislative contests – as opposed to those for City Council -- the few people who do go to the polls will find that the field of candidates has already been narrowed by an arcane political process and the influence of political party leaders.

CHOOSING CANDIDATES

The whole system of choosing a party nominee and getting on the ballot in a special election for State Senate or Assembly is complex and inexplicable (if you really want the details, click here). In short, though, it comes down to this: A small number of party activists and insiders select their party’s nominee. There is no primary. Both the Democratic and Republican parties, along with the Working Families, Independence and Conservative parties – may field candidates. But in many legislative districts in the state, including the one on Manhattan’s East Side, one party or the other holds a huge edge in party registration. That party’s candidate starts special election day holding an enormous advantage.

The winner of this year’s special elections for legislature will have to face the voters again in a regular election in 2008. But given that incumbents have a nearly 100 percent reelection rate in New York, the victors have a good chance of serving a lifetime in their offices in Albany. According to figures compiled by Citizens Union Foundation (which publishes Gotham Gazette), 32 percent of the current members of the State Assembly and 29 percent of state senators first won their seats in a special election.

PLAYING THE GAME

Virtually no one defends the process. But even its critics use it to their advantage.

Last year Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer called the system "ridiculous." At that time, voters on the West Side of Manhattan were about to go to the polls to choose a new member of the State Assembly – a vacancy created when Stringer won election to the borough presidency the previous November,

That opinion did not prevent Stringer from using the process to make sure that his favorite candidate, Linda Rosenthal, won the Democratic nomination. And it didn’t stop Rosenthal, who admitted that the “process may stink,” from accepting the nomination. While a few candidates waged a quixotic challenge against her, Rosenthal won – and remains in the Assembly.

There are exceptions. Last year, in the contest for another Manhattan Assembly seat, Sylvia Friedman, a longtime Democratic activist, got the Democratic nomination apparently due largely to her ties four local Democratic clubs.

Friedman’s victory was short lived. In a real Democratic primary – open to all registered party members not just club loyalists – she lost to Brian Kavanaugh, a former mayoral aide and chief of staff for Councilmember Gale Brewer. In beating Friedman, Kavanaugh pulled off the political equivalent of a baseball triple play – ousting an incumbent legislator.

THE PRICE OF DEMOCRACY

Like any elections, the special ones cost money for printing election materials and hiring and training poll workers. In City Council races, candidates get public funds to run their campaign. According to Citizens Union, the estimated cost of a special election in the city is $350,000 to $400,000.

THE NEXT ELECTIONS

The following special election have been scheduled:

-- Staten’s Island’s North Shore will elect a replacement for longtime Assembly member John Lavelle on Tuesday. The Democrat would normally be heavily favored in the contest but the presence of an Independence Party candidate, who unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination, could complicate things. The race could also bring Staten Island either its first openly gay state legislator or its first black elected official.

-- Staten Island’s South Shore: Also on March 27, voters will fill the seat formerly held by Vincent Ignizio, who was elected to City Council in February. This district is normally Republican, but the Democrats have sought to boost their chances by giving their party line to a registered Conservative Party member.

-- 40th Council District: Voters in central Brooklyn will again go to the polls to try to choose a successor to Yvette Clarke, who left City Council when she was elected to the U.S. Congress in November. In his continuing effort to become the first Haitian on the City Council, Mathieu Eugene, who won the first special election but apparently failed to meet residency requirements, will face a smaller and somewhat different field of opponents.

And if that’s not enough, there’s still that election on the East Side of Manhattan. Assuming Grannis eventually wins confirmation, Kellner, despite an impressive raft of endorsements, will still have to face the voters if he hopes to get to Albany.

Â