Marjane Satrapi's drawing about a teenager's life in Iran

There are many ways of looking at what is being called the cartoon crisis, even in New York.

1. Demonstrations

A dozen cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad –- one of them with the prophet in a turban shaped as a bomb with a burning fuse -- were first published last September in a newspaper in Denmark. It was not until January of this year, according to an account in The Washington Post, that the cartoons began sparking violent protests around the world, resulting so far (as of mid-February) in the deaths of at least 45 people, according to a count by the Associated Press.

There have been demonstrations in New York City as well: About 1,000 Muslims protested in front of the Danish Consulate on a Friday in February; there was an earlier demonstration at the United Nations.

2. The Cartoons And The NY Press

Several European editors have lost their jobs for publishing the cartoons, and 11 Muslim journalists in five countries, including Jordan, Algeria and Yemen, were arrested for doing so.

In New York City, four members of the staff of the New York Press quit when the publisher yanked the cartoons right before publication. (The articles, and 12 cartoons, that were going to run have been published on a Web site called New Partisan) So far, no local newspapers have published the cartoons except the New York Sun.

While in Qatar, U.S. Undersecretary of State Karen Hughes said U.S. newspapers generally did not reprint the caricatures ''because they recognize they are deeply offensive, even blasphemous to the precious convictions of our Muslim friends and neighbors.'' Others say it is from fear.

3. Political Cartoons And The Press: Losing Their Voice

When Daryl Cagle talks about a cartoon crisis, he is not only talking about the reaction to the Danish cartoons. A cartoonist himself for MSNBC, Cagle runs a popular Web site that offers both an index of political cartoons and news about cartooning. (It probably has the most comprehensive updates about the events surrounding the Danish cartoons).

It is clear from his site that he feels that political cartoonists are under siege in the United States as well, albeit for different reasons. The number of full-time staff editorial cartoonists has shrunk from more than 200 in the 1980's to under 80 today. Major newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times and Baltimore Sun are now without a staff cartoonist, and even the newspaper cartoons that remain (as cartoonist Scott Santis observed on Cagle’s blog) “are more often jokes than commentary.” Recently, Cagle wrote: “A knowledgeable source tells me that the Village Voice, the New York alternative tabloid with a great tradition of editorial cartoonists going back for decades -- including Jules Feiffer and Ed Sorel -- will stop running editorial cartoons, and any future cartoons will be non-political.”

4.Offensive Cartoons On Display In NYC, I

There are a half-dozen offensive cartoons –– not online, not from Denmark, but in a New York City museum. They are ugly caricatures of black New Yorkers, wearing ludicrous costumes, speaking in ignorant but pompous dialect, and generally putting on airs.

“Not a single image of black New Yorkers survives from their first 170 years in the city,” explains a wall label in “Slavery in New York,” an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society. Then, in the 1790s, “black people appear in the pictures of the city for the first time.” The first pictures are landscapes dotted with a couple of “hardworking if nameless blacks.”

It was not until slavery was abolished completely, in the 1820s, that caricatures of black New Yorkers started appearing in the local press. They were not the only group to be caricatured; immigrants too were a target. But “black New Yorkers came in for especially vicious lampooning” – and some half-dozen examples hang on the walls of the exhibition.

5.Offensive Cartoons On Display In NYC, II

On the second floor of The Museum of Jewish Heritage: A Living Memorial To The Holocaust, is a room with some half-dozen Nazi-era caricatures of Jews, most of them on the front page of a notorious German newspaper called Der Sturmer – a Jew accosting an innocent blonde in a train station, Jews collecting the blood of children, a Jew looking like a kind of bloody King Kong destroying a German town. There is also a children’s board game called Jews Out. “The objective of the game is to collect Jews, who â€mar’ a German town by their presence and their â€parasitic businesses,’ and deport them to Palestine.”

Elsewhere in the exhibition is a poster by American artist Ben Shahn, created in response to a Nazi massacre in the town of Lidice, Czechoslovakia: Under the title, “This is Nazi Brutality,” it shows a figure with a hood over his head, his hands chained (an image that in 2006 startlingly evokes a more recent event.) Although commissioned by the U.S. Office of War Information, the wall label notes, “it was deemed too violent for mass distribution.”

6. What Is Offensive Art?

Nobody is calling the Danish cartoons works of art -- indeed, New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman called them “callous and feeble” provocations meant to “score cheap points about freedom of expression.”

Still, The Washington Post’s account explains that Flemming Rose, the editor for the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten who commissioned the cartoons, did so in part after having read “that museums in Sweden and London had removed artwork that their staff members deemed offensive to Muslims.”

Many non-Muslims looking at the cartoons see them as bland or unclear, and don’t understand what all the fuss is about; some of those offended reply that this lack of understanding is part of the problem.

The question of whether the religion of Islam deems any depictions of Muhammed to be offensive is reportedly one debated by Islamic scholars. In The New Yorker magazine, Jane Kramer writes: “The Koran says that there can be â€nothing like a likeness’ of God, but in fact it makes no reference to images of the prophet to whom the interdiction was revealed. (It is the Hadith, Islam’s early narrative, that forbids the faithful to represent him.) And, as Islam spread to Persia and India, civilizations with strong representational traditions, artists did paint him.”

It is worth noting that an analogous prohibition exists in the Judeo-Christian tradition, as expressed in the King James Bible translation of the Second Commandment: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image [in other words, an image sculpted, carved or engraved], or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

A Web site called Religious Tolerance points out that “a strict interpretation of this verse would prohibit…erecting nativity scenes at Christmas, hanging religious art in churches, allowing wedding photographers into the sanctuary, installing stained glass windows…that include images of people and animals, using children’s Bibles which are decorated with pictures,” etc.

7. What Is Offensive Art In NYC?

In his article on the Danish cartoons, “A Startling New Lesson in the Power of Imagery,” Kimmelman asked: “Have any modern works of art provoked as much chaos and violence?” He noted that the 1926 painting by Max Ernst, The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child before Three Witnesses, was recently shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art without protest. He brings up a handful of past controversies, such as the Sensation show at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, which is best-known for inspiring then-Senatorial candidate Rudy Giuliani to create a Decency Commission and threaten to bankrupt the museum. But Kimmelman left out the long litany of battles in the culture wars taking place in New York -- including, mostly recently, the successful effort to chase the Drawing Center out of the World Trade Center site, and the attacks on The Last Supper also at the Brooklyn Museum, and on artwork by Robert Mapplethorpe, Andres Serrano, Richard Serra, John Ahearn...

There is, in fact, a great deal of artwork in New York that one group of people or another have found offensive. Kimmelman attributes this to what he calls the "knee-jerk baiting of traditional authority" inherent in modernism, the efforts by modern artists to "pander to a like-minded audience by goading obvious targets hoping to incite reactions." We live in a society where it is considered a compliment to call something "irreverent."

Others say that the artist's role is to show a culture things about itself that people do not want to see, or are not ready for; "it's through art," Arthur Miller wrote, "that the generations converse with one another."

8. Islamic Art Not On Display In NYC

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has three portrayals of Muhammad in its collection, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“A spokeswoman said none of the Met's depictions of Muhammad -- one from 15th century Afghanistan, one from 16th century Uzbekistan, one from 16th century Turkey -- had been displayed for years. The Met's Islamic galleries are closed for renovation until 2009.”

At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which also has such work, Islamic art curator Linda Komaroff said: "We've always known about these images, and no one's ever had a problem, because they are respectful.... I wish this whole issue would go away because it's so incendiary."

9. “Islamic Art” On Display In NYC

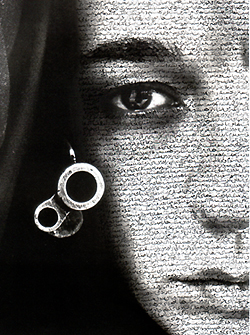

|

"Speechless" by Shirin Neshat |

The label “Islamic Art” does not appear in a new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art entitled “Without Boundary: 17 Ways Of Looking,” even though 15 of the 17 artists “came from the Islamic world but do not live there,” in the words of curator Fereshteh Daftari. The artists were born in Iran and Iraq, Pakistan and Egypt, Istanbul and Beirut. They live in London and Paris, Buenos Aires and (six of them) in New York. Some of their work takes the classic traditions of Islamic art as they are understood in the West –- calligraphy, carpets, miniatures -– and turns them on their head in some way. “The most Islamic-looking object,” Daftari points out, is by one of the two American-born artists, Mike Kelly, whose woven silk carpet replaces the traditional red with the green of his ancestral Ireland, and throws in a few shamrocks. “The purpose of this show,” the curator said, “is to prove how reductive â€us-them’ is.”

The most startling image may be “Speechless,” by Iranian-born New York artist Shirin Neshat’s, in which a woman is wearing a gun barrel as an earring, and her face is covered with calligraphy-like text, the writing (as the catalogue explains) “a eulogy to martyrdom in the name of Islam, quoted from the writings of the contemporary Iranian poet Tahereh Saffarzadeh.” It is part of a series she called “Women of Allah.”

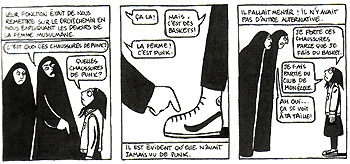

The most ironic work in the show is surely Marjane Satrapi’s drawings, taken from a comic book she entitled “Persepolis,” named after a capital city of an ancient empire, that chronicles the life of a teenage girl in the post-revolutionary Iran of the 1980s who is drawn to Michael Jackson and denim jackets and Nikes sneakers. In a series of panels, the girl is stopped by “guardians of the revolution” who interrogate her about her sneakers, her jacket, and her Michael Jackson button, “that symbol of decadence.” (Remember, this takes place in the early 1980s, before he had become a symbol of decadence in the West as well.) It’s not Michael Jackson, she lies. “It’s Malcolm X, the leader of black Muslims in America.”

In the forward to her comic book, Satrapi (who now lives in Paris) laments that “this old and great civilization” where she grew up is being discussed entirely in connection with “fundamentalism, fanaticism and terrorism….I know this image is far from the truth.”

...*** Â