Thomas Kelly, author of "Empire Rising," joined Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club on September 28 for a wide-ranging discussion about the Empire State Building, political corruption, Irish immigrant in New York and writing about New York City.

Thomas Kelly, author of "Empire Rising," joined Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club on September 28 for a wide-ranging discussion about the Empire State Building, political corruption, Irish immigrant in New York and writing about New York City.

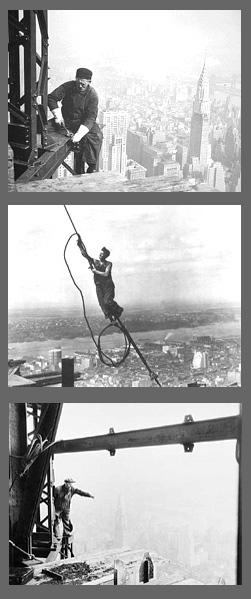

Gotham Gazette: Your book tells the love story of two Irish immigrants: Michael Briody, an ironworker working on the construction of the Empire State Building, and Grace Masterson, a bohemian artist-type living on a houseboat on the Brooklyn waterfront -- something I don't believe you can do anymore.

Thomas Kelly: No, but you could then. She's based on a great aunt of mine who did live on a houseboat.

Gotham Gazette: Both of these characters have a connection to the Empire State Building. They are also somewhat involved in the inter-related worlds of Tammany Hall and organized crime. The setting seems to be a crucial part of the book. There's a lot going on in the New York that Mr. Kelly describes, big development and labor issues, the thriving Irish immigrant community, and, of course, money and corruption in government. Why did you decide to write about New York during this time period?

Thomas Kelly: My previous two books dealt with a lot of the same themes but in a contemporary setting. I worked in construction for about ten years, and that has reared its head in all my books.

James Elroy once asked, "How do you write about crime and not write about the Kennedy assassination?" In New York City's history, as far as construction, the Empire State Building is it. More than all the other great projects -- the Brooklyn Bridge, the aqueducts, the water tunnels, the other skyscrapers -- the Empire State Building represents New York City to America, and America to the world.

For a novelist it's very rich territory -- this whole transition, the mafia and the gangs becoming ascendant, and switching to an Italian and Jewish thing from an Irish thing. The Irish have kind of made it by this point: They've got the mayor, the governor, the police department and the fire department. They're barely into law yet, but they're moving up, moving on.

As a novelist, all of this is going on on the macro level. On top of that I put these characters, some of whom were based on family members. Michael Briody was a great uncle of mine who met a certain fate in the Bronx at that time. He was an Irish immigrant. It was one of those things that gets whispered about. He's buried at St. Raymond's in the Bronx. I went to visit his grave and decided to write a book describing what happened to him. Of course it's fiction, but it's within the realm of possibility.

Grace Masterson is based somewhat on a great aunt of mine. When I was fairly well into the book, I found out this woman lived on a houseboat in Williamsburg. My father's sister told me about this aunt they used to visit in the 1920s, how they would take the train to Manhattan and then the ferry across to Greenpoint. I thought, "Wow, this is great stuff!" I already started the book, so I had to go back and put her there. For me, she's a stand-in for the novelist. It's like getting that little bit of remove from Manhattan: She's across the river, painting, taking in the sights.

My family came in the 1920s from Ireland. I think about the Empire State Building going up at the time. I wanted to write about family history, and they sort of melded at that time. I don't want to write a nonfiction story of my family. I just wanted to take a little bit of the truth and imagine the world they lived in.

THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING: PUNCTUATION POINT TO THE ROARING '20s

Gotham Gazette: Why does the Empire State stand out as unique, as opposed to say the Chrysler Building, which was built a couple years of earlier as the world's tallest building?

Thomas Kelly: For a lot of reasons. It's not that much taller than the Chrysler building or 40 Wall Street. But the Empire State Building is a much more massive structure. The Chrysler Building has about 18,000 or 20,000 tons of structural steel; the Empire State Building has 65,000. So it's three times as big, even though it's only about 15 stories higher.

The Empire State Building was also the punctuation point to the Roaring '20s. Those other buildings went up when things were still going crazy. Then they demolished the Waldorf-Astoria hotel to build the Empire State Building. The destruction of that building started the day the stock market crashed. It's a symbol of ambition, drive and human endeavor. It's going up and the city is falling into depression, as is the county around it.

In addition, there's the involvement of Al Smith and the whole history of Tammany and what it symbolized to Smith. So I felt it had a much richer history than those other two buildings. There were a lot more stories to tell.

TAMMANY HALL

Gotham Gazette: The other plot line in the book is Tammany Hall. From the beginning of the book there's a sense that Tammany Hall has created a well-oiled machine to make itself rich. But there's also a feeling of an impending reformist wave. Fiorello LaGuardia actually did get elected as a reformer several years later. So is this, in a sense, Tammany's last hurrah?

Thomas Kelly: Tammany is a fascinating institution for a lot of reasons. We see it today as a negative thing, as these corrupt party bosses. But you have to understand Tammany. It was started by Aaron Burr and staunch, Anglo-Protestants around the Revolutionary War.

At times, it was wholly corrupt, but it did a lot of things for a lot of people, especially in the 19th century. There were no government programs for anything at that time. Basically you had a barbaric capitalist system, and if you didn't survive, nobody cared. Tammany and other machines around the country provided services, jobs, they paid doctor bills, they brought a turkey on Christmas. And the only thing they wanted in return was your vote. They recognized this was democracy and whoever gets the most votes wins. They very shrewdly capitalized on that. At times they got out of control.

The 1920s fascinate me for a lot of reasons. It was the most revolutionary decade in American history. People talk about the 1960s, the sexual revolution. Nonsense. The 1920s, that was the real sexual revolution; the '60s were like a rich kid aftershock. The modernization, the movement from rural to urban. The country kind of exploded in the 1920s, in a lot of positive ways, and Tammany was in the mix of this.

The back story here is really Prohibition. In 1919, the politicians are telling the gangsters what to do. By 1930 -- and this is what I tried to get at in this book -- the paradigm is shifting. There's this noble Protestant effort to keep the animals in the ghetto, but out of the saloons, scrubbed, up to work early and praying to a Protestant God at the end of the day. And this backfired horribly. It created, for the first time and maybe the only time ever, a real power in the underclass and the underworld in America. By 1930s, a real reckoning is at hand. The balance is shifting, and the guys with the guns are saying to the politicians, "Wait a minute, why should we listen to you anymore?" That's what I wanted to get at.

The book lays out the back story of what led to the downfall of Jimmy Walker a year and a half or two years after the book ends. Franklin Delano Roosevelt is cunningly playing his angles, knowing that to run for president in 1932 he needed Tammany locally, but nationally he needed some distance.

MACHINE POLITICS, THEN AND NOW

Gotham Gazette: In your other books, you also write about machine politics, which in some ways, are still with us. Can you contrast the machine politics of the different eras?

Thomas Kelly: One anecdote that describes this difference very strongly is that at the Democratic Convention in 1932, a fellow named Jimmy Heinz, a big Tammany leader from Upper Harlem, had as his roommate, very openly, Lucky Luciano. It's the equivalent of Clarence Norman and John Gotti being roommates. That's not going to happen.

Then, it wasn't seen as doing something wrong; it was seen as "there's power to be exercised, we control it now, and this is how we're going to exercise it." Tammany, and even some gangsters, would say, "Wait a minute, you got your money from putting ten-year-olds in coal mines and slave trading. Now we want to get our piece of the pie and we're the bad guys?"

The guys who ran Tammany Hall in 1920s had a very big say in who became the Democratic nominee for president. They could deny someone, or basically appoint someone. They had a lot more power.

But it's the same stuff now. The buying of judgeships -- that's how Judge Crater [a state supreme court judge who is a character in "Empire Rising"] got his judgeship. Now they try to hide it more, but it still goes on.

TAMMANY'S GOOD SIDE

Jacqueline Arasi: People could go to a Tammany Hall location and get help, that's how they got to be known. They were very nice -- even when I was passing out leaflets for La Guardia they brought us coffee and cake. There was a real positive element to Tammany Hall. I think it's a more positive history than a negative history.

Thomas Kelly: Absolutely, there was a real positive element. Unfortunately, the negative history has been written by their enemies, and you're looked at like you're abetting some sort of criminal enterprise if you point out they did good things. For the Catholics and Jews at the time, the Protestant churches would give out money and say, "Sure we'll help you out; why don't you convert?" All Tammany wanted you to do was to show up on Election Day.

When the demographics started changing in the 1880s and 1890s, when waves of Italians and Eastern European Jews and Poles started coming, Tammany was very smart. Guys like Charlie Murphy and Big Tim Sullivan saw the writing on the wall. They reached out to those communities, took care of them and brought them into the fold. They did a lot of things: getting people jobs, bailing kids out of jail who had done something stupid, and on and on.

Gotham Gazette: But Tammany wasn't just asking for your vote. Aside from enriching themselves, they were involved in things like widespread voter fraud and so on -- correct me if I'm wrong.

Thomas Kelly: Well, what's your definition of fraud?

The period I'm talking about in the book was a little more sophisticated than it was 20, 30, 40 years before when it was guys with bats showing up at voting booths. Again, it's one of those things -- there's no black and white here -- people trying to survive and trying to get ahead. The decisions they made are probably not dissimilar to the ones we'd make.

CONSTRUCTION AND CORRUPTION

Gotham Gazette: How much documented corruption was there in the building of the Empire State Building?

Thomas Kelly: Well, there's almost none documented, and much of what today we would consider corruption was accepted business practice then. For instance, at that time if you wanted to break a slab of sidewalk, you'd give a kickback to the building department.

Two building code changes made the Empire State Building possible. One was elevator speed, and the other was steel thickness. The technology in steel had advanced so much by the 1920s that you could use much thinner, lighter steel, which was much stronger than the old stuff. If you're going up 102 stories, it's something you want. If you have people going up so high, how can you do so without faster elevators.

The changes were mysteriously vetoed twice by Mayor Walker, and then, after the materials were already ordered, he reversed himself. I find it hard to believe, given what went on at the time, that there wasn't a significant payment to somebody. I imagine a scene at the beginning of the book with a million dollar payoff.

Walker's this great figure. He died broke, basically. The Protestant experiment to keep the animals in line created power and corruption. Walker rode that wave, and did it with a lot of charm, and people loved him -- not just the Irish. He was a very charismatic guy; he was always witty and good at tweaking the noses of the powers that be outside of politics. He raised his salary from $25,000 to $40,000, which was a lot of money back then. There was an outcry in the press, and he responded by saying 'Well, imagine what I'd charge if I worked full time!'

But he was very popular. He brought in baseball on Sundays, got boxing legalized as a state assemblyman. Then, at the end of the story, he's going to Yankee Stadium and gets booed. Even he knew that the Depression changed everything. All of a sudden it's not good times, people are suffering. And there's this guy driving around in his Duesy with a floozy.

THE CHANGING CULTURE OF CONSTRUCTION

Gotham Gazette: The culture of construction is a big part of the novel. Do you have a sense of how much that's changed, how different it's going to be for the workers who, for instance, build the Freedom Tower if they ever start building it?

Thomas Kelly: It's probably changed a lot less than people think. Different materials, but a lot of the process is exactly the same. There's a line I use in the book that, during the 1920s, building the skyscrapers is the closest peacetime equivalent to war -- all the planning and energy that goes into it. They're still huge undertakings. People still get hurt, people still die. It's hard work.

Gotham Gazette: Is it still mainly Irish, or has that changed?

Thomas Kelly: Construction unions in this city have long been very tribal, and they still are, though less than they used to be. I was a sandhog, and that's been Irish and West Indian since the days of the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. You have the third or fourth generation working there.

The ironworkers are mainly Irish. Most come from Newfoundland -- they call them "fish" or "newfies." There's this sort of exaggerated myth of the Native American ironworker. Joseph Mitchell started it when he started writing about it in the 1940s, and Gay Talese continued it with "The Bridge," writing about the Mohawks. They were never more than five percent of the union. They got into it because, when they were building bridges upstate and Canada, the ironworkers brought some of the locals into the union, and they happened to be Mohawks. It became this weird reverse racism with some of these writers. Not to take anything away from what these Mohawks did and still do, but it's kind of funny how that happens.

In the beginning, a lot of Swedes and Norwegians came off the tall ships and were used to working in heights. They lived in Bay Ridge. There's a little bit of everything now: Italians, African Americans, Puerto Ricans. But still the biggest group would be Irish, and the biggest subgroup would be the newfies.

It's different with different trades. For the carpenters, there used to be about a half-dozen locals: the Jewish local, the Italian local, the black local, the Irish local. There's always a lot more peaceful co-habitation and intermingling than the negative stuff, but the negative stuff gets the press. Building trades now are almost 50 percent minority. I don't think Wall Street has gotten that close.

WORKING CLASS NEW YORK

Gotham Gazette: In the New York you describe, the culture seems very much influenced by the working class. I don't think many people would say that the working class is driving the image of New York City today. What do you think happened?

Thomas Kelly: That's a 12-part lecture.

Let's focus on Manhattan. I hate it when everyone focuses on Manhattan, but let's face it, when the rest of the world thinks about New York City they think about Manhattan from about 96th Street down. In the 1930s, that slice of Manhattan was filled with middle class, working class, and poor people. It was a lot of immigrants and a lot of regular people, families. What has happened -- and what is happening now at probably a faster rate than ever -- is the displacement of the population that can't afford it. I saw in the paper that 44 percent of the apartments in Manhattan are $1 million apartments.

A friend of mine once said that he liked New York better when the corporals ran the city. And what he meant by that was that you didn't have to be a big shot to be treated like a big shot. The city was run by the workers, and they felt invested in the city. Things have changed a lot in that regard and not always positively.

I write mostly about that other New York, which for me is the real New York. I try to go against the images of New York that go out to the world. It's not Donald Trump; it's not Central Park South. It's a much, much bigger story, and unfortunately over the last few generations less and less of that story is being told. What's going on today with the Dominicans and Bangladeshis, it's not much different from the story of the Jews and the Italians and the Irish. They're hard-working people who came to a crazy place from far away and want to make their lives better. That story is ongoing. Unfortunately as it becomes less white, it probably also becomes less attractive.

THE MYSTERY OF JUDGE CRATER

Kevin Baker: Any theory on the Judge Crater bones?

Thomas Kelly: In the book I deal with the disappearance of Judge Joseph Crater who, for those of you who don't know, disappeared off the face of the earth in August, 1930. He became one of the most famous missing people in American history, to the point that if you didn't show up for work they'd say you pulled a Crater.

I have my version of what happened in the book. It's not a big part of the book, but it's emblematic of the level of corruption at the time. Judge Crater represents the audacity of the corruption. Someone said, "Alright, we'll just disappear a state Supreme Court judge off the street." That just doesn't go on in America. This isn't Columbia during the drug wars. Things got so out of hand because of Prohibition.

RESEARCH VS. IMAGINATION IN HISTORICAL FICTION

Gotham Gazette: How much of your work is based on research and how much on imagination?

Thomas Kelly: I think it was E.L. Doctorow who, when asked how much research he does, said "just enough." A lot of historical novels are written by historians. They're histories; they're not stories. I didn't want to do that. I wanted to be meticulous about detail, and I missed one or two. I had Babe Ruth batting fourth in the Yankee lineup, when he wore number three because he batted third; and I had him using a doughnut on his bat. Luckily, someone caught them for me. These tiny details are important. As a storyteller you're creating an illusion, and anything that jars people out of that is bad.

The great thing about the 1930s is that there were still enough people who had been adults at the time. They were 90 when I talked to them, so they would have been 20 at the time. I talked to a friend of mine's great aunt who just died at 100. She was the daughter of Tammany Hall district leader in Hell's Kitchen. I also talked to, I think, the last guy alive who worked on the Empire State Building. He gave me great details. He was 17 at the time.

The amazing thing about the Empire State Building is that they built it in 13 months, and they built it on straight time - 40-hour weeks with no overtime. This man told me that on Friday they would pick a floor, say the 34th floor, and when the bell sounded on Friday afternoon they would bring barrels of beer and girls up and they would drink and gamble and have a casino in the sky.

He told me: "I'd leave around midnight, and come back Monday morning and they'd still be there, then they'd go right back to work!" If they hadn't done that, they'd probably have built it faster! That's a detail you're not going to find in a history book.

The other thing I did was go to the public library and read the tabloids of the day, which put you there in a way the history books just don't. The tabloids of the 1930s, they make the New York Post seem like Readers Digest. It's just blood and guts and sex; it's just pre-code America, it's amazing. It was the Wild West.

IRISH IMMIGRANTS AND THE WARS IN IRELAND

Gotham Gazette: How much of the involvement of Irish immigrants with the Irish Republican Army and the wars in Ireland was true?

Thomas Kelly: In 1923, you had the Irish War of Independence and following that immediately the Irish Civil War. One side decided to sign a treaty with the British, which cordoned off a part of Northern Ireland, something that we still deal with today. The other side said we shouldn't give the British anything. It degenerated into this nasty, ugly civil war that lasted 18 months. Only about 660 people were killed, but it wasn't armies; most of it was assassinations, atrocities.

The losing side of this war became the second largest Irish migration to the United States. That was during the 1920s, and that's when my family came over. This was a very rural, very embittered population. They were as angry with the Irish who sold them out as they were with the British. They were mostly young.

When you look at the South Bronx, where a lot of them went, the second or third generation Irish didn't accept them. The established immigrants were like, "Who are these animals coming off the boat?" The Irish weren't accepted by the established Irish.

This was a very impoverished population, and what's amazing to me is how few of them got involved in the rackets. Very few of them became gangsters at a time when there was plenty of opportunity to get involved and make good money. So these really were committed soldiers to the cause.

Gotham Gazette: Were they people who fled the war, or people who moved to the United States with the specific intent of carrying on the war?

Thomas Kelly: They were the losing side of the civil war. A lot of them left because they couldn't get jobs or they were shut out of opportunities in Ireland. Some of them just came here and said, "the hell with Ireland," and never looked back; others continued the struggle. This is sort of a twilight period for the IRA, but there was still very much going on.

I get into this in the book with Michael Briody. He's trying to raise money and send guns back. There was a committed cadre of people at this time that was devoted to that struggle. I found notes of meetings of the American political wing of the IRA where they had a debate over whether they should open a speakeasy to finance their cause. They voted against it because they didn't want to be seen as criminals. They were revolutionaries.

A lot of them got involved in starting the subway union. Here is a great New York story that hasn't gotten a lot of play. They were Irish, and they went to the church, which said "Commies! Get out of here"; The Ancient Order of Hibernians said, "What are you crazy?" So they ended up going the Communist Party, which was Eastern European Jewish. This combination of these Irish farmboys and Eastern European Jewish intellectuals created the Transport Workers Union.

In the 1920s the subways were all privately owned railroads, and they were some of the most vicious employers in the country. There were big strikes that were viciously put down, violently put down. And one of the ways they organized the unions was the Irish guys would speak in Irish -- Gaelic. They would hold secret meetings. This was necessary because spies for the companies called beakies were paid an extra dollar a day to rat out anybody who was a union sympathizer.

So all that's going on, and I have these characters that are caught up in these crosscurrents.

Gotham Gazette: Did the involvement of immigrants in New York have much of an effect on the situation in Ireland itself?

Thomas Kelly: No. It was a tragic lost cause by that point. These guys were dreamers; they were madmen to a certain extent. It was a pretty pathetic effort at that time.

And you can't underestimate the power of the idea of America and these freedoms. Many of the Irish coming over here, they were fleeing not just the Brits, but the Catholic Church, and now their fellow Irishmen.

That's what happens with this character. First he falls in love, and he had never been in love. This guy joined the British army when he was 15 to fight World War I. He comes back and gets involved in the IRA, fights against the British, fights the civil war. Now he ends up in America. He's 30 years old, he's been at war his whole life. He falls in love with this woman who is from where he's from; he's got this job he loves. And all of a sudden he's like "Wow, maybe the past should just be the past."

And I think that sort of thing happens all the time in this city. People come into Kennedy Airport every day leaving something like that behind. Some of them think they'll get back to it. My grandparents never went back. A lot of them never did.

WRITING ABOUT FAMILY

Gotham Gazette: You mentioned that your family was the basis for some of the characters in the book. What did they think of it?

Thomas Kelly: Well, for me all that matters is my aunt Mae, my father's sister who died last year. She was quite a character. She came over at seven years old and went on to become an English teacher at Roosevelt High School. She was always the one who gave me books, and inspired me to read.

My first two books were filled with a lot of profanity. The first book has about 38 homicides. So the English teacher reads the first book and says, "Obviously you're a good writer but the language is a bit rough." She doesn't mention the 38 homicides -- how Irish is that?

So I really wanted to tip my hat to her, because a lot of the inspiration was family stuff. So the F word appears once. She said she really enjoyed the book. And I asked her if she noticed anything and she said: "Yes, I can read it to my grandchildren."

But the real beauty of writing fiction is that you can say "Well, no, that wasn't you." And it wasn't.

Sylvia Price: My grandparents are getting older, and they don't remember much. It's hard to get them to talk.

Thomas Kelly: I couldn't get everyone to talk, and you've really got to work your way into it. For many of these families coming to America there's almost this insane need to be clean, to be perfect, to be upstanding. They want to be accepted. It was that whole "work hard and do the right thing, and don't allow yourself to justify those stereotypes."

I would just start asking her about what it was like. For me, we had this whole conversation about the iceman, and then the coal man, and then Jimmy the tea man who came by horse and wagon to the Bronx. Just details like that. From that, it would lead her to something else.

People are uncomfortable talking about themselves, and a past they'd maybe rather forget. So it's kind of tricky. But I'm compelled to get those stories, because I believe that when those people die, those stories die with them.

WRITING ABOUT WORK, WRITING ABOUT NEW YORK

Gotham Gazette: You mentioned a problem you had with Gay Talese's "The Bridge." Your book reminded me in many ways of that book, about the building of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge. The day-to-day routines and interactions of the people who were working on the bridge and, in your book, on the Empire State Building, seemed very similar. What did you get out of that book?

Thomas Kelly: It's a great book, and the focus on the Mohawks is legitimate. I wish there were more like it. I think he's a fabulous nonfiction writer. He's very meticulous in detail, very graceful.

Gotham Gazette: Are there any other books that you would recommend, either about this topic, or about New York in general.

Thomas Kelly: There aren't a lot of books about work. It's kind of sad. In one of the reviews of "Empire Rising," the guy reviewed it very positively, but said it was a throwback to whole socialist-realist novels of the 1930s, like "Christ in Concrete." But you can count these titles on one hand.

Who built the pyramids? A bunch of slaves. Who built the Roman aqueducts? We don't know. What were their experiences? We don't know.

Book Club member: What are you working on now?

Thomas Kelly: I'm writing two pilots for television, one for HBO and one for CBS. The one for CBS, One Police Plaza, is kind of a cop thing: the West Wing meets the NYPD. The other is about Manhattan at night, it's about a family. One brother's a night watchman type and the other's a sandhog. It's about how the city is changing. One brother is just home from prison after 15 years, comes back to the West Side and it's like stepping onto the planet Mars.

I'm starting a new book. I want to do this epic thing about the rise and fall of postwar New York. It opens in 1945 when the guys get back from the war and ends around the time of the Knapp commission [on police corruption] in the 1970s. It's a little more about cops and a little less about construction. It's really about how the city evolved and changed over that quarter century. I want to show cops in a place like New York as those who have a front-row seat to history and use them as a way to look at these big social changes.

Book Club member: Are you going to use family members for source material?

Thomas Kelly: I had an uncle who just died who was quite a character. He arrested the guy who killed Kitty Genovese. At 80 he was 6-foot-3, 220. I can imagine what it was like in 1963 trying to keep a confession from him. Just the story of a guy like that, starting in the 1940s, with all the stuff going on in New York, race and class, money, and change.

The funny thing about New York is we don't have a Saul Bellow. There are so many stories to be told. How do you wrap your arms around it? In a way it's true, but I want to attempt broader stories and the way all these worlds interact.

New York is a way that this interaction goes on, as much as it's becoming polarized. Those guys living in the penthouses are still going to have to get out on the streets and go past the kids from the projects. That doesn't happen in a place like Greenwich, Connecticut. It doesn't happen in a lot of places in the world. We have this forced interaction that has made New York probably a much greater human experience than other cities. We can't ever be LA.

From a storyteller's point of view there's a lot to be said about New York. I feel like I could write for the next 1,000 years and not crack it.

Â