Shouldn’t Statewide Elected Offices be Held by People Who Are Elected?

Gov. Hochul & then-Lt. Gov. Benjamin (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of the Governor)

It is not unreasonable to assume that our six incumbent statewide elected officials first got their current jobs by being elected to them. Not unreasonable, but mostly not so.

Actually, four of the six incumbents in these jobs – Governor Kathy Hochul; recently-resigned Lieutenant Governor Brian Benjamin; Comptroller Tom DiNapoli; and U.S. Senator Kirstin Gillibrand —first came to serve in their roles through the operation of provisions in law for filling vacancies due to resignation, death, or removal for cause.*

Moreover, even though the state constitution requires that no person filling a vacancy in elective office shall hold his or her appointment “longer than the commencement of the political year next succeeding the first annual election after the happening of the vacancy”…three of these four officials (Senator Gillibrand excepted) have served or were selected to serve out the entirety of the term to which their predecessors were elected (Article XIII §3). And now we again face the prospect of using a vacancy-filling process to fill a statewide office, for Lieutenant Governor, this time in the midst of an election campaign.

What’s going on here?

Governor

Article XX of New York State’s 1776 constitution provided that “...in case of the impeachment of the governor, or his removal from office, death, resignation, or absence from the state, the lieutenant-governor shall exercise all the power and authority appertaining to the office of governor until another be chosen…” This provision was retained in the updated 1821 constitution. But language adopted at the 1846 constitutional convention, and still in force, provided that upon succession “…the powers and duties of the office shall devolve upon the lieutenant governor for the residue of the term, or until the disability shall cease.” (Article IV §6).

Thus when Governor Andrew Cuomo resigned on August 24, 2021, Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul became governor and will serve as such for the one year and 128 days remaining of Cuomo’s four-year term (barring removal, death, or resignation).

Lieutenant Governor

New York’s four state constitutions and statutes pursuant to them have all been silent on whether and how to fill vacancies that arise in the lieutenant governorship. Beginning with the succession of Lieutenant Governor John Taylor after Governor Daniel Thompkins was elected Vice President of the United States in 1817, the practice was established of leaving the office vacant, with its duties performed by the Temporary President of the State Senate, and devolving sequentially if necessary to others in a line of succession specified by statute.

In 2009 Lieutenant Governor David Paterson succeeded Governor Elliot Spitzer. Faced with a chaotic political situation in the Legislature, a daunting budget crisis, and a potential scandal in his own office, Paterson appointed Richard Ravitch to serve as Lieutenant Governor under the general provisions of the Public Officers Law. The governor’s action was subsequently found constitutional by the state’s high court, the Court of Appeals.

In accordance with this precedent, Lieutenant Governor Brian Benjamin was appointed by Governor Hochul on August 26, 2021. Though Benjamin was intended to serve out the remainder of Hochul’s term — as the state constitution provides that “No election of a lieutenant-governor shall be had…except at the time of electing a governor” — his resignation in the midst of a campaign finance scandal has again opened the office to be filled by gubernatorial appointment.

U.S. Senator

The 17th amendment to the United States constitution provides that the “executive authority” of each state, if authorized by that state’s legislature, may temporarily appoint a U.S. senator in the event of a vacancy”…until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct. In New York, the governor is given this power of temporary appointment.

In June of 1949 Democrat Robert F. Wagner resigned from the U.S. Senate. Two weeks later Republican John Foster Dulles was appointed by Republican Governor Tom Dewey to replace him. Since the outset of popular elections of U.S. Senators, New York law requires that “…vacancy… [elections were]… to be held at the next annual November general election which occurred at least 30 days after the vacancy arose.” In a special election held in 1949 on the next following general election day, former Governor Herbert Lehman defeated Dulles and took the seat by a vote of 2,582,438 to 2,384,819.

Lehman’s winning margin was provided by the Liberal Party’s cross endorsement. Republicans were convinced that the simultaneity of the special election for the Senate seat with that year’s mayoral election in Democrat-dominated New York City elevated turnout there, also contributing significantly to Dulles’ loss. In 1951 the Republican-controlled state government amended the Public Officers Law so that thereafter persons appointed to fill U.S. Senate vacancies would serve “… until a replacement can be elected at the next congressional election,” removing the possibility of election to fill vacancies in odd numbered years.

Currently, the Public Officers Law specifies 60 days before the primary date in each even-numbered year as the cutoff for determining whether the election will take place that year at the general election or whether it must await the next congressional election.

Kirsten Gillibrand was appointed on January 26, 2009 to fill the vacant U.S. Senate seat created by the resignation of Senator Hillary Clinton when she became U.S. Secretary of State in the Obama administration. There was no congressional election in 2009. Senator Gillibrand served as an appointee until winning a special election on the general election day held in November 2010 to complete the remaining two years of Clinton’s six-year term. She has since been elected twice to full six-year terms.

Comptroller and Attorney General

It was not until the 1846 constitutional convention that popular election was adopted for filling these two and nine other statewide posts. Previously these officials were appointed, under New York’s first constitution by a Council of Appointment and its second (after 1821) by the Legislature. During the time that the appointing power was with the legislature, so was the power to fill vacancies.

The democratizing 1846 constitutional convention also adopted the principle that vacancies in these newly elective offices be filled as soon as practicable by election, and with language that, as noted, persists in New York’s current constitution, that “…no person appointed to fill a vacancy shall hold his office by virtue of such appointment longer than the commencement of the political year next succeeding the first annual election after the happening of the vacancy.”

Within this context, the Legislature sought to preserve what it could of the vacancy-filling power by statute. But legislative sessions were very brief in the 19th century, statewide officials’ terms of office were short (mostly two years), and these were key jobs both for the party patronage and the administration of state government. To assure that they were filled in a timely manner if the Legislature was not in session, therefore, a statute was adopted in 1849 that provided for interim gubernatorial appointment of “some suitable person” to fill vacancies in these positions until “the commencement of the political year next succeeding the first annual election” was adopted, while leaving with the Legislature final authority for making these appointments or making others when it reconvened.

Over the ensuing decades constitutional reforms reduced the number of New York’s statewide elected officials. As a matter of actual practice, power to fill vacancies in the positions of Comptroller and Attorney General came increasingly to reside with the Governor. Parallel to earlier statutory action taken regarding filing vacancies in the U.S. Senate, in 1953 Republican Governor Thomas Dewey proposed to the Legislature constitutional amendments requiring election of the Governor and the Lieutenant Governor on one ballot, barring elections for Comptroller and Attorney General except in (even numbered) gubernatorial election years, and empowering the Governor to fill vacancies in these two statewide officials by appointment.**

These were to be presented to the voters at referendum in a single question. But regarding vacancy-filling, instead of gubernatorial appointment the Legislature presented and the voters passed an amendment that delegated to the Legislature itself the task of establishing a vacancy-filling process for these offices. Then it adopted a law returning to the use of the practice of legislative appointment. The combined effect of this change and the bar on elections for Comptroller and Attorney General except in gubernatorial years was that appointees could serve in these elective offices for the entire remainder of the term to which the departing incumbent was elected.

The New York state constitution currently directs the Legislature to provide by law for filling vacancies in the positions of Comptroller and Attorney General. The process that it specified requires the Legislature to meet in joint session and elect persons to these offices if a vacancy occurs.

State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli was elected on February 7, 2007 by such a joint session to serve the remaining three years and 319 days of the four-year term of Comptroller Alan Hevesi. Hevesi, who was just reelected the previous November to a second term, resigned in December of 2006 as part of a plea bargain in a case involving his unlawful employment of state workers for personal purposes. DiNapoli has since been elected Comptroller three times.

Recent Proposals

Legislation has been periodically introduced and reform suggested to democratize New York State’s processes for filling vacancies in statewide elective office. In his constitutional history of New York, published in 1995, Peter Galie noted that constitutional amendments had received the first of two required passages in separate sessions of the Senate and Assembly “…which would eliminate the power of the state legislature to provide for the filing of vacancies and would delete the prohibition that no election for…[Comptroller or Attorney General]…shall be held except at the time of electing the governor.”

In 2010 the New York City Bar Association Committee on Elections called for a return to historic practice, with elections to fill U.S. Senate vacancies still held on the general election day, but possible in both even and odd numbered years. The Governor would retain the power to appoint an interim Senator, but the elected Senator would enter office earlier, “…upon the issuance of a certificate of election.”

Legislation first entered in 2007, and proposed again in the current session (bill A0596/S03876) by Democratic Assemblymember Kevin Cahill and Republican Senator Joseph Griffo, requires the Governor to call a special election to fill Comptroller and Attorney General vacancies. In a parallel bill (A00708/S03781), Cahill and Griffo do not require the Governor to call a special election, but allow him or her the discretion to do so for these two offices and United States Senator.

A version most recently introduced by Assemblymember Steve Hawler and Senator George Borrello (bill A06297/S03875), both Republicans, leaves initial responsibility for filling vacancies in the offices of Comptroller and Attorney General with the Legislature, but requires election to follow on the first general election day at least three months after the vacancy occurs.

Finally, regarding the lieutenant governorship, Republican Assemblyman Michael Tannousis and Democratic Senator Neil Breslin — on the model of the U.S Constitution’s 25th amendment process for filling a vacancy in the vice presidency — would condition appointment to fill a vacancy on the provision of advice and consent by both legislative houses (bill A08243/S2503).

Making Elected Offices Elected

New York’s provisions for filling vacancies in statewide office are diverse, complex, and riven with elements entrenched in law to achieve political advantage. Their combined effect is to devitalize the state constitution’s commitment to popular rule. Especially now, a time when democracy is under siege, it is crucial that all the paths to power in state government remain as democratic as possible, commensurate with efficient, effective governance.

A comprehensive, democratic approach to filling vacancies in top elective positions would have these elements:

1. Strengthen and reassert the constitutional principle that statewide elected offices must be filled by popular election as expeditiously as practicable.

2. For vacancies that occur early enough, before the start of the annual nominating process set out in the election calendar for the year, conduct an election to fill the office on the general election day. For vacancies that occur after the nominating process has started, hold the election on the general election day in the next following year. (Note: Avoid special elections for which there is added costs, turnout is lower, influence is exercised by the person charged with calling them, as they may result (New York City experience shows) in multiple elections for a single office in a brief span of time.)

3. Specify in the state constitution processes for immediately, automatically filling the vacated office on a temporary basis, with unelected persons serving in an acting capacity until an election is held. Whereas Lieutenant Governor acts as Governor; Executive Deputy Comptroller acts as Comptroller; Solicitor General acts as Attorney General. For U.S. Senator and Lieutenant Governor vacancies, interim acting appointments would be made by the Governor with advice and consent of both legislative houses required. For Comptroller and Attorney General, deputies specified in a succession statute should assume interim responsibility in the period preceding the required election. No non-elected person would hold unqualified status in these positions.

***

*They are among the three New York U.S. Senators, ten governors, eleven comptrollers and six attorneys general who first entered their offices in accord with vacancy filling positions. Comptrollers and Attorneys General were not chosen by popular election until 1846. U.S Senators were not chosen by popular election before 1913. James Mead is not included. No appointment was made prior to the special election to fill the Senate seat vacated by Royal Copeland at his death in July of 1938.

**This followed the earlier statutory change (1951) providing for holding required elections to fill vacancies in U.S. Senate seats only in even numbered years (see above). Republicans believed that statewide elections in odd numbered years favored Democrats, especially if there was a mayoral election in New York City scheduled that would boost turnout there.

***

Gerald Benjamin is Emeritus Founding Director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The New State Budget is a Start, But New York Still Needs to to Do More for AAPI Communities

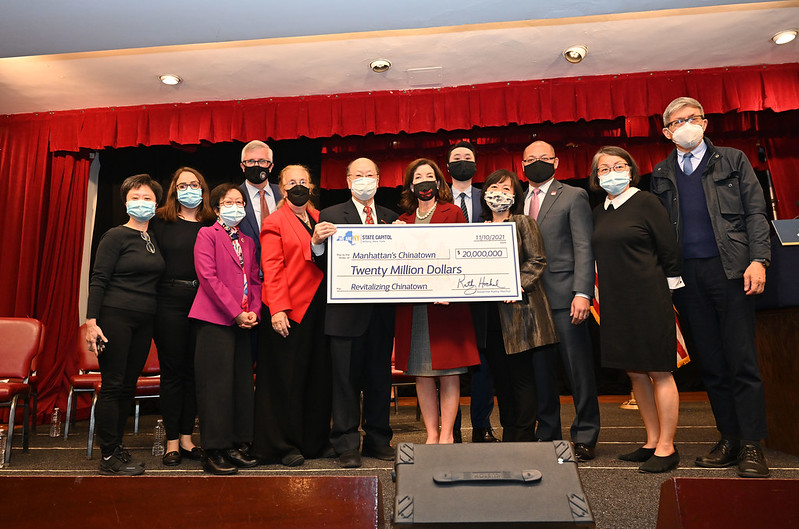

Gov. Hochul presents funding for Chinatown (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of the Governor)

I immigrated from Taiwan to the U.S. at age 27, with just two pieces of luggage, because of my belief in the American Dream.

Like most Asian-American immigrants, I understand the struggle of acclimating to a new country and a new city. You must navigate new systems and overcome language barriers. And now, as Asian hate crimes continue to soar, many in the Asian-American Pacific-Islander (AAPI) community find ourselves fearful within our own city and grappling with how to protect ourselves.

The recently-passed New York State fiscal year 2022-23 budget will include $20 million to support community organizational efforts to aid the AAPI community in New York, which is double what the state spent on AAPI funding last budget but only a third of the $64.5 million requested by the newly-formed AAPI Equity Coalition this year.

While this is a good start in providing Asian-American organizations with more funding, more needs to be done to solve the systemic issues that are at the root of the problems facing the AAPI community today. The state needs to prioritize combating the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, bridging the language gap for Asian immigrants, and providing support to the grassroots organizations already within New York’s AAPI communities.

As crime rates have gone down in New York City overall, hate crimes against Asian-Americans have increased by 400%. My heart breaks every time I see another story about violence against Asian-Americans, especially in a place like New York that boasts inclusivity and diversity.

Just last month, a man hit a 67-year-old woman in Yonkers 125 times just because she was Asian.

Now we have women and seniors lining up for access to free pepper spray, just to feel somewhat secure against what seems like daily senseless and hateful acts of violence. We cannot allow Asian people to continue to live in fear of being attacked or discriminated against any longer.

In order to prevent future hate crimes, we need to provide Asian communities with culturally-sensitive resources to apprehend and prosecute those committing these acts of violence, as well as develop a program for non-English speaking victims to safely report hate crimes and to receive counseling and support.

The Asian immigrant community, in particular, has very few resources because of language and cultural barriers. During my 10 years working as chief of staff for State Assemblymember Peter Abbate, many constituents came to me and our office when they had issues with the social services, education, and health care systems, often because they could not understand how things worked and there were little-to-no appropriate resources to help.

So many lives could be improved by expanding language access to government agencies and programs, providing interpreters at polling sites, and supporting nonprofit organizations working relentlessly to provide crucial services to immigrants.

Asian communities are historically underserved, underfunded, and underrepresented in New York, which is why I continue to call attention to their needs. Now more than ever we need to show AAPI New Yorkers that they are being heard, that they are being seen, and that they are being protected.

We need to bridge the gap between the AAPI community and state government — this is why I hope to be in Albany next budget season to fight for more funding for the AAPI community, and provide it with resources that are long overdue.

Asian-American immigrants should have the resources they need to not only survive but thrive as they pursue their American Dream, just as I have.

***

Iwen Chu is running to represent the newly-created State Senate District 27. She is President of Star and Stripes Democratic Club and was Chief of Staff for Assemblymember Peter Abbate for the past 10 years. On Twitter @Iwen4NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Change I Didn’t Know NYCHA Needed

Repairs at NYCHA (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

More than three decades ago, my family was one of the first to move into Washington Heights Rehab, a New York City Housing Authority development. It’s in this development where I’ve since raised my three children and it’s the place that I’ve always called home. But like other NYCHA developments across the five boroughs, our building became the subject of disrepair, deferred maintenance, and difficult living conditions.

That’s until an initiative led by a mission-driven team of developers transformed our apartments into modern, beautifully-renovated homes. The initiative delivered the change my building most certainly needed, and I believe more broadly offers unexpected hope to the city’s 400,000 public housing residents.

About 15 years ago, the deteriorating conditions of Washington Heights Rehab started to come to a head. What was once a pleasant place to live began to crumble into a building that was an unhappy, unhealthy, and in some ways, unsuitable place to call home. For whatever reason – whether it was funding or an overworked housing authority – maintenance work came to a grinding halt. We began to witness water coming down walls, increased amounts of mold, more rodents, and frequent garbage problems. It got to a point where essentially everything in our building was damaged.

I realized then that our situation wasn’t necessarily unique but that didn’t make it any easier to handle. As a mother, I felt neglected and hopeless. The conditions made providing and caring for my family that much harder. As a tenant president, I felt disempowered. I knew I had to do something to help myself, but, as the voice of my community, I also knew I had an obligation to help my neighbors. However, no matter how much I tried, little improved because funding for NYCHA had gone dry.

Fortunately, change came – albeit in a way that wasn’t necessarily expected. During the summer of 2019, I learned about a team of non-profit and for-profit developers and social service-providers that would soon be leading the management, rehabilitation, and renovation of Washington Heights Rehab. As it turned out, the team known as the PACT Renaissance Collaborative (PRC) also was tasked to lead the same massive rehabilitation work at 15 other developments in Manhattan as well. We had initial meetings with their representatives where they explained the plan, and where we were also given the opportunity to be heard.

In 2019, we were skeptical; we had been promised change before when in fact nothing did change, and the idea of a private developer coming in to be that change certainly raised some eyebrows, too. But nearly three years later, we’re ecstatic because what’s occurred since those initial meetings has been transformational. PRC has fully renovated each and every apartment in our development with new kitchens, bathrooms, living rooms, flooring, windows, and doors; brought new life to commons rooms and shared spaces; and they have ensured that when a repair or maintenance is needed it’s taken care of.

This work and their effort have rejuvenated Washington Heights Rehab and we’re truly grateful for everything that’s been accomplished. After more than a decade of uncertainty, we feel like we’re now shown the respect that every tenant – especially public housing tenants – should be given by their landlord and property managers.

I understand that PACT Renaissance Collaborative is not the only team tasked with bringing new life to public housing across the five boroughs, so I cannot speak to the quality of work being completed as part of NYCHA’s larger PACT program. What I do know, though, is that when the right team is chosen to lead the rehabilitation and management of NYCHA buildings through PACT – and when residents are heard in the planning processes of the program – that incredible change can occur. My building and the quality of my living conditions are a testament to just that.

To all my fellow public housing residents: we’ve been through a lot over the years. But, I now have hope that we are turning a corner on this crisis of disrepair thanks to mission-driven teams like the PACT Renaissance Collaborative. From the bottom of my heart, I encourage NYCHA residents to open their hearts and minds to the opportunity that change might present through this PACT program.

Ask your questions, make sure to be heard, and demand accountability from those leading the PACT process. But know that the program does hold the potential to transform your apartment, building, and life for the better.

***

Margarita Duran is a 35-year NYCHA resident and TA President of Washington Heights Rehab.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NYS Public Service Commission: Do the Right Thing for Frontline Communities

New York City from above (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

It doesn't often happen that New York State has an opportunity to take decisive and meaningful action to address deep-rooted issues that have plagued the Bronx, New York City, and our state for way too long — environmental injustice and climate change.

This month, the seven members of the New York State Public Service Commission hold our fate in their hands as they vote on the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE), a permitted and shovel-ready renewable energy project contracted with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). CHPE is poised to create sorely needed jobs this year, deliver clean electricity year-round to New York City by 2025, and begin to finally break our unhealthy dependence on fossil fuels. It's a classic upstate-downstate dynamic, with most commissioners living in northern New York making a decision that will directly impact us here in the city.

The Bronx is ground-zero for the asthma epidemic in New York City, with hospitalization rates 70% higher than the rest of the city and 700% higher than the rest of the state. The areas of the South Bronx and Northern Manhattan have one of the highest death and disease rates from asthma in the country. And this enraging reality is a result of the historical injustice in our politics, planning, and perverted economic development on the backs of frontline communities of color. The Bronx was chosen by design to bear the brunt of the state's addiction to fossil fuels, from transportation infrastructure to power generation. We can no longer tolerate this construct.

90% of New York City's power comes from burning toxic fossil fuels. In this twisted reality, our underserved communities are literally paying to be polluted, just as fossil fuel generators fleece our wallets without consequence. This winter we were slapped with historic spikes in our electricity bills because we are forced to depend on volatile natural gas prices. Enough is enough. The New York State Public Service Commissioners should approve the Champlain Hudson Power Express contract that will provide clean power to over 1 million homes, slash air pollutants by 20%, displace fossil fuel generation by 25%, meet 20% of the city's power needs, contribute 7% to reach our state's 2030 clean energy mandate, and help lower wholesale energy prices. It's a no-brainer.

CHPE is committed to union labor and working with local communities to ensure there is diversity, equity, and inclusion at the center of this project. I have witnessed this firsthand by participating in the foundation of CHPE's working group on the subject made up of local environmental justice, workforce development, and community leaders. In addition to this concrete commitment to diversity, the project is launching a $40 million green jobs training fund available for residents of underserved communities, including the Bronx, to gain the skill-sets necessary to pursue a career in the green economy.

Inaction is not an option we can live with any longer. If we forgo CHPE, the next comparable project is guaranteed to be more expensive and come into service later. I call on the Public Service Commission to do the right thing and approve CHPE.

***

Assemblymember Kenny Burgos represents parts of the Bronx. On Twitter @KennyBurgosNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Divorce Got Easier During Covid; That Shouldn’t Change

Brooklyn municipal building (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

A few months ago, in my role as a family attorney, I settled a fairly ugly child custody dispute in Queens Family Court. As my client and I debriefed, he asked me, “I probably saved some money with this being entirely online, huh?” I didn’t have to think twice. “Absolutely,” I told him. “At least a thousand dollars.”

I was underestimating. After I did the math, I estimated that my client saved around $3,750 solely because the case was litigated virtually, as nearly all family law cases have been for the last two years, owing to New York’s covid-necessitated court shutdown. And this was a relatively simple case, where the only issue was custody of kids – if it had been a complex divorce with financial issues to be determined in addition to custodial ones, he would have saved many thousands more.

In normal times, attending court involves sitting around from 9:30 a.m. for a morning case, or 2 p.m. for an afternoon one, until the court officer tells you it’s time. Sometimes you get in right away – others, you wait hours. Sometimes you get kicked past lunch hour, which goes till 2:15 p.m. Sometimes you see the judge, they give you a few morsels of judicial wisdom, and they tell you to go in the hallway and work it out and come back later. Waiting is baked into the process.

Virtual court, with appearances held remotely, has rewritten this process. For the last two years, lawyers have gotten specific appearance times, every time. If the court tells you to log in at 11 a.m., you will almost certainly be heard by 11:05. The longest I’ve waited for a virtual appearance to begin was 20 minutes. And if we get kicked out and told to negotiate and come back later, we can do it on the phone, hang up when we’re done, and work on other cases. For lawyers used to thumb-twiddling for hours, this certainty is a welcome scheduling gamechanger. And it’s even better for clients, because it saves them serious money.

Like nearly all attorneys, I charge for in-person waiting time, because time spent in a courthouse is time I can’t spend in my office working for my other clients. My hourly rate for my custody client’s case was $375, which is on the low end of New York City family lawyers. We can safely estimate an average of 120 minutes of wait time per appearance if we had been in-person. Do the math, and he saved $3,750, just because we didn’t have to show up in person. For most parents and spouses, this is not chump change – it's a rent or mortgage payment, maybe two, it’s a family vacation, it’s savings.

Family litigation is already prohibitively expensive for most families. Unlike corporations, which have legal funds, or personal injury litigants, whose lawyers work on contingency, spouses and parents have direct exposure to legal fees. New York has the second-highest solo or small firm lawyer rates in the country, averaging out to $357 an hour. (Big family law firms here charge more – I know divorce lawyers who top $1,000 an hour.) And make no mistake – litigating a divorce or custody case to resolution takes many hours. There’s a reason most family attorneys can tell you about the client who took out a usurious “divorce loan” they’ll be paying back for a lifetime. By making family disputes cheaper, virtual court reduces the chances that a parent or spouse will bankrupt themselves to fund it.

There are other benefits to remote court for family law matters. For disabled clients, even making it to the courthouse can be a difficult journey, or even an impossibility. Litigants must take at least a half-day off work, something only the privileged can afford, and pay a babysitter. Allowing parents and spouses to log in on their phone or laptop from home or the job eliminates all these obstacles to access. Being remote has also allowed me to take on more pro bono work – I can represent one needy client in a courthouse far from my home, only because court has been on my computer. If her case moves back to in-person, I am honestly not sure what I’ll do.

And that day is coming. Across the state, courts are moving back to in-person appearances, including some courts in New York City. Put aside, for a moment, the covid risks, although that alone is enough reason to consider this foolhardy. Consider why exactly we are demanding divorcing spouses and parents in custody battles take off work to sit in a courthouse for hours and watch their savings drain away.

Seasoned divorce litigators will tell you that virtual court is strange, different, that they need to look a witness in the eyes when they cross them. And that’s true. I conducted one trial virtually during the pandemic, and I didn’t love it. Critically, though, formal trials, with testimony and cross-examination, are a rare part of family litigation – the vast majority of cases settle first. But even those cases that settle can require five, ten, thirty court appearances, all before anyone is sworn in as a witness and trial begins. There is simply no reason to have these appearances in person.

Too many parents and spouses find themselves caught up in the brutal maelstrom of litigation before they even realize it’s happening. Costs build up quickly — quicker than most litigants predict. I don’t say this lightly, I have seen lives destroyed by this process. I have seen parents on monthly payment plans to lawyers that equal the amount they are receiving in child support. I have seen pensions sold and 401Ks cashed out to pay for trials. For anyone but the very rich, litigating a divorce or custody case can be the perfect financial storm.

Remote court is not even close to a cure-all. But it is a serious policy change that has real, positive effects, and that in some small way makes the nightmare of family law litigation more bearable. New York would be wrong to go back to “normal,” when normal has caused so much unnecessary harm. Fine, hold trials in person. But other than that, divorce and custody cases should be conducted virtually, even after this pandemic is finally behind us. Access to justice demands it.

***

John Teufel is an attorney. On Twitter @JohnTeufelNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

An Early Test of The Adams Administration’s Values and Tech Prowess

Participatory government in-person (photo: New York City Council)

In 2019, New Yorkers voted overwhelmingly in favor of establishing a Civic Engagement Commission that would modernize how the city and its residents worked together to identify and solve problems at the most local levels. That commission hasn’t been earning itself many headlines, but the participation platform it set up at participate.nyc.gov could support world-class civic engagement programs. Whether or not the administration of Mayor Eric Adams uses it to do that will be an early test of its basic competency and technology prowess.

Participate.nyc.gov is much more than a basic government website. It’s a deployment of an open source participatory democracy platform called Decidim. First founded in Barcelona in 2016, Decidim is free and open source software used by dozens of municipal governments around the world including Helsinki, Mexico City, Zurich, and Milan. The software is a successor of Consul, a similar platform that facilitated genuinely innovative and wildly successful crowd-sourced city planning, participatory budgeting, and decision-making in Madrid, Spain.

The idea behind Decidim and Consul is simple: give the public a single, unified, open source platform and standard set of tools for participating in local civic engagement programs. These platforms allow city residents to be organized into different types of districts to have discussions, make proposals, vote on projects, take surveys, and generate the type of feedback that city agencies and elected officials can and should use to understand how best to improve our neighborhoods, city, and government operations.

Since New York City’s deployment of Decidim is just beginning to be used in a few City Council districts participatory budgeting processes, it’s difficult to see the platform’s potential. To do that, it’s best to visit decidim.barcelona (turn on Google Translate if you don’t read Spanish) and see how they’re using the software. On that site you’ll see two main menu items, which translate to Participatory Processes and Participation Bodies, which is more easily understood as Processes and Spaces.

Processes are civic engagement programs, such as a participatory budgeting cycle, a city planning project review, or a charter revision.

Spaces are groups of people, often divided by their district, operating under a defined set of rules about membership and governance.

By applying processes to spaces, the Decidim system deployed at participate.gov.nyc could host many of the city’s existing civic engagement processes immediately, right “out of the box,” with no need for any expensive custom development.

Here are some examples:

-City Council members and districts could use it for participatory budgeting;

-Community boards could publish news, events, meeting minutes, files, videos, surveys and more – replacing their websites;

-City commissions could replace their websites with Decidim as well, and use its collaborative editing and commenting features to enable residents to attach their ideas and comments to specific language in a document.

Beyond these basics, the system could be used for so much more: to

-host discussions about pending legislation;

-gather feedback about land use issues;

-provide a unified calendar of city agency outreach events;

-facilitate petitioning the city council to introduce legislation.

The list could go on.

All of these new tools and features can frighten politicians and civil servants because they’re experts in the current systems for public engagement and any change could alter the power dynamics to which they’ve become accustomed and dominate. As such, there is natural resistance to utilization of different, better platforms and processes. Fortunately, Mayor Adams claims to be tech literate, eager to reform city government, and focused on public participation.

During the mayoral election, Adams pledged to establish MyCity, “a single portal for all City services and benefits.” One of the key “services and benefits” the city offers its residents is civic engagement. As such, a unified platform that many different agencies use for civic engagement purposes fits nicely with Adams' vision.

And, as an open source platform built with the popular framework Ruby on Rails, Decidim is a platform that the city can own and run itself, without needing to pay expensive IT consultants or exorbitant licensing fees. Indeed, it's the perfect project for the Digital Service Organization (DSO) the city should have already launched.

Indeed, the participate.nyc.gov system could become an integral component to the MyCity dream. Decidim’s login system uses open standards that could and should be integrated with the inevitable user authentication system that is a prerequisite for MyCity. And its data, formatted into configurable open data feeds, can and should flow elegantly into other city information management systems, such as City Record event feeds or City Planning project pages.

To see the true value of Decidim, the Adams administration must develop an understanding of the open source concept that makes it possible. It’s hard for many people to understand how sophisticated software like Decidim could be available on the internet to download for free, with no limitations on how or by whom it's used. It seems too good to be true, but it is.

Open source technologies like Linux, WordPress, and Bitcoin get a lot of the headlines, but there are actually hundreds of thousands of open source applications out in the world, and that number is expanding all the time. Most of those applications are components that must be combined with other ones to make a system, but some are full-fledged applications like Decidim.

As I’ve mentioned in other articles, open source is transforming how the government delivers services all over the world, but New York City’s IT bureaucracy and poor leadership have not adopted proven techniques to benefit from these advancements because powerful special interests make tremendous amounts of money by keeping the city in the technological dark ages.

Companies that run core city software systems like Microsoft, Dell, Tyler, ESRI, Accenture, and others want to keep the city addicted to their proprietary software systems. To achieve that goal, these companies have fused themselves with city agencies like the Department of Information Telecommunications and Technology (DoITT), which are much more comfortable signing expensive software contracts with these companies than they are deploying and managing open source software systems themselves. Meanwhile, city technology executives routinely work at vendors before and after their time in government. The revolving door spins very quickly.

If Mayor Adams develops an understanding of how to effectively use open source software to make the city more efficient, effective, and equal, then there is no limit to the amount he could achieve. He has a great opportunity to start off on the right foot by organizing a DSO unit to manage the open source Decidim software at participate.nyc.gov and aggressively utilize that software to deliver New Yorkers the world-class civic engagement experiences we deserve.

Delivering compelling civic engagement programming through participate.nyc.gov is a great way for Adams to prove he has the technological prowess and genuine desire for reform that he claimed to have during the campaign.

It’s time to deliver.

***

Devin Balkind is a nonprofit executive, civic technologist, and startup advisor running for Public Advocate as the Libertarian Party nominee. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.

The Pragmatic Progressivism of Ritchie Torres

Rep. Ritchie Torres (photo: Jeff Reed/City Council)

As congressional representatives seek re-election this year, there is one member of Congress who doesn’t need to worry about having an opponent: Rep. Ritchie Torres. At the time of this writing, there is no word of a candidate circulating petitions to challenge Torres in this June’s Democratic primary. As political insiders well know, it is rare for an incumbent in New York not to have a challenge.

Many may have taken notice of Torres’s popularity in his congressional district, as is evident in this Data for Progress poll. According to the poll, Torres enjoys a 73% favorability rate in the 15th Congressional District.

The rise of Ritchie Torres is one that I foresaw in these pages some years ago. I believe the rest of the country will continue to share our New York experience of Torres as a thoughtful legislator who has an uncanny ability to dig through complex policy issues and who articulates his positions clearly and concisely.

Equally fascinating to me has been Torres’ political philosophy since 2013, a posture of pragmatic progressivism. The “pragmatic” part of this posture has earned Torres the scorn of some other progressives.

Contemporary political progressivism in the United States has several variants. The current trajectory of progressive politics can perhaps be distinguished between those on the socialist left and those on the liberal left, who consider themselves more pragmatic.

By “pragmatic” I am not referring to the philosophical school of thought of pragmatism made popular by the likes of William James and John Dewey in the 20th century. Rather, I refer to “pragmatic” as an electoral and governing approach to politics that seeks to achieve social ends through the most practical means possible.

These two distinguishing markers of political progressivism–the socialist left and the liberal left– are hardly a recent phenomenon. Since the 20th century, progressive politics has been quite diverse. Interestingly enough, the socialist left once had a similar influence in New York and national politics to what it has now, though the impact is perhaps a bit greater now if we consider the number of socialists that are being elected to local office. The recent electoral successes of socialists are due to their intentional efforts to work within the Democratic Party instead of functioning as a third party as they did decades ago.

Perhaps the most prominent and influential socialist figure in 1930s electoral politics was Norman Thomas, a member of the Socialist Party of America. Thomas’ charm, charisma, and intellect helped to catapult the socialist agenda into the national political discourse.

Yet this socialist influence began to wane with the social progress achieved through FDR’s New Deal initiatives. What replaced it for the next few decades was the influence of the liberal left.

What has been deemed “liberal left” I call pragmatic progressivism. And it is in this wing of progressive politics that Ritchie Torres resides. Pragmatic progressives seek most of the same goals as other progressives: universal healthcare, adequate funding for education and housing, fair wages, among others. The “pragmatic” element in this type of progressivism acknowledges that to function, politics must maintain a healthy equilibrium between competing interests.

The key difference between the socialist left and pragmatic progressives lies in the paths they take to achieve progressive aims. Pragmatists assert that the attainment of progressive goals may entail negotiating with those competing interests that are at different points along the political spectrum. Therefore, pragmatists make no bones about the fact that they must work within an imperfect and indeed broken system full of people with different opinions and constituencies that make these negotiations necessary. Pragmatists see these negotiations as necessary for the work of progress.

If Norman Thomas was the face of the socialist politics that preceded current socialist movements, like the contemporary Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), then the theologian and ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr, in the same era, represented the pragmatic progressivism exemplified today by Ritchie Torres.

In the 1930s, Niebuhr was part of the Socialists of America party and even ran for office twice on their ballot. The realities of World War II and the social and economic impact of FDR’s New Deal changed his politics, leading him eventually to co-found New York’s Liberal Party and later the Union for Democratic Action, which eventually became the Americans for Democratic Action. Niebuhr understood that the seeking of political perfection was far from realistic; therefore the necessity to seek compromise. He believed that the idealism of the socialist left, as was evident by their propensity to clamor for pacifictic alternatives during World War II, was indeed an attempt to seek the perfect. Yet, Niebuhr would assert that the perfect can’t be the enemy of the very good.

Torres reflects in word and deed the type of progressive politics espoused by Niebuhr—seeking progressive goals by balancing realities of politics and governance.

When have we seen Rep. Torres’ inclination toward this kind of pragmatic progressivism? Let’s take a look at his stance on the “Defund the Police” movement prominently espoused by those on the socialist left. Speaking to Jose Diaz-Balart on MSNBC last month, Torres said, “...any elected official who’s advocating for the abolition and/or even the defunding of police is out of touch with reality and should not be taken seriously.” Torres prefers to speak of a “reform the police” type of movement, one that acknowledges the necessity of policing for ensuring public safety while acknowledging also that there are structural deficiencies within police departments that need deep and sustained reform. Torres says, “What most New Yorkers want is not less policing or more police, but better policing — more accountable and transparent policing.”

Perhaps this stance of Torres’s points to his inclination to work within a broken system in order to seek necessary changes from within rather than seeking a total abolition of a system that doesn’t work for many, particularly for communities of color. Hence, Torres has developed positions and backed legislation that seek to attack root causes of crime like poverty and housing instability, and pursues policies to address them.

Torres’ position on the “Defund the Police” movement and his penchant for reforming systems from within deficient structures could perhaps be seen in a police reform bill fight in 2017, during his tenure in the New York City Council.

The 2017 Right to Know Act, a controversial and much-debated set of police reform bills, sought to deter police abuse and to ensure transparency in any interaction between an officer and an individual.

There were two bills in the Act, one introduced by then-City Council member and now Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso and the other introduced by Torres. After hearings and negotiations, Torres made changes to his bill.

The Reynoso bill was championed by many police reform advocates, earning the praise of Monifa Bandele, a spokesperson for a prominent coalition, since Reynoso’s bill would bring “transparency and accountability regarding searches during non-emergency policing encounters that have no legal basis other than a person’s supposed consent."

Of Torres’ bill, Bandele said: “This NYPD bill being advanced by Torres is neither the Right to Know Act nor a compromise, but political backroom dealing and a surrender of legislative independence to the NYPD and the Mayor.” Bandele’s statement reflected the sentiment of other reform advocates, who felt that the updated version of Torres’ police reform bill conceded too much to the NYPD.

Torres indeed negotiated particulars of the bill with NYPD representatives and the mayor’s office. But he insisted that any concessions made to the de Blasio administration would ensure the needed transparency in a number of interactions between police and individuals.

Torres earned the scorn of both police reform advocates and the police unions. History has shown that this type of criticism from both extremes is often the result of political decisions made by pragmatic progressives. Acknowledging the need for negotiations between disparate political interests and views in order to achieve progress on behalf of the citizenry never earns them friends at the extremes and most devoted parties, but does win them broad support among the more pragmatic general population.

Torres has done this again with his position on the status of Puerto Rico, siding for statehood for the Caribbean island, a position favored by conservatives on both the island and the mainland. A little over two weeks after winning his congressional race in a historically majority-Latino (and Puerto Rican) congressional district that was once represented by Herman Badillo, Torres penned an op-ed declaring his support for Puerto Rico statehood. His statehood stance can be succinctly captured by his declaration that “As Americans, we must speak out forcefully against the de jure disenfranchisement of our fellow citizens in Puerto Rico, for it represents a deep rot at the very core of American democracy, not to mention a manifestation of the very systemic racism against which millions have stood in protest.”

Using the lens of systemic racism to critique the current status of Puerto Rico is in essence utilizing a progressive principle (the fight against systemic racism and the acknowledgement of Puerto Rico’s colonial status) in order to stand on the side of statehood, a position long held by mostly conservatives in Puerto Rico.

This position places Torres on the opposite side of the issue from the other two Puerto Rican congressional representatives in New York City, Reps. Nydia Velázquez and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, both of whom have introduced the Puerto Rico Self-Determination Act of 2021. The bill seeks to give Puerto Ricans on the island the opportunity to finally determine their status through an elaborate process that would include publicly-financed elections and a convention with delegates elected by the Puerto Rican people. Torres believes that Puerto Ricans have already determined their will by a recent referendum in which voters selected statehood as their preferred option.

While the police reform bill and Torres’ position on the status of Puerto Rico may cause some to question his progressive bona fides, it is also important to remember his championing of a myriad of progressive issues. For instance, Torres has introduced a bill that would require the Federal Home Loan Banks to drastically increase investments in affordable housing, community development, and small business lending. And of course, on the issue of public housing, few elected officials in New York have been as relentless and consistent on the need to revamp our public housing facilities through massive federal investment. More recently, Torres led a push, supported by Ocasio-Cortez, demanding that billions in funding be secured for public housing and rental assistance.

It is difficult to peg Torres solely on one end of even the progressive spectrum. Throughout his career as an elected official, Torres’ positions have reflected the thinking of a pragmatist who acknowledges the need to balance interests for the greater goal of achieving progressive values.

***

Eli Valentin is an adjunct professor at Iona College. He writes regular columns for Gotham Gazette, largely focused on Latino politics in New York City, and is a frequent guest political analyst at Univision NY. On Twitter @EliValentinNY.

***

Eli Valentin is a political analyst and author of the forthcoming book, Reinhold Niebuhr: A Political Life. On Twitter @EliValentinNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Should Celebrate New York State’s Birthday on April 20

New York (photo: Governor's Office)

New Yorkers have a birthday of sorts coming up. On April 20, 1777, the Convention of Representatives of the State of New York, an ad hoc group of patriot leaders elected the previous year to guide New York’s Revolutionary War efforts and develop its first constitution, finished its work on that document.

That act brought New York State into existence.

It was a remarkable document, prepared on the fly by the group that had kept out of reach of British forces by fleeing from New York City (just before it was occupied by the British in 1776) to White Plains, to Fishkill, and finally to Kingston where it completed its work on the document.

The work was done in such haste that the final version of the document included cross-outs and marginal corrections. There was no time to even make a clean copy before the document was read publicly for the first time by the convention’s secretary on April 22. He climbed atop a flour barrel outside the building where the group had met and read it aloud to Kingston citizens. Then, the new document was rushed off to the printer.

The document declared that the convention, acting “in the name and by the authority of the good people of this State, doth ordain and determine and declare that no authority shall in any pretense whatever shall be exercised over the people or members of this State but such as shall be derived from and granted by them.”

In 1777, a document purporting to represent the consensus and will of the people was a startling, radical departure from the past.

The original copy of the first constitution is preserved in the New York State Archives, and can be read online at the Yale Law School Avalon Project. William A. Polf’s 1777: The Political Revolution and New York's First Constitution provides a good introduction. It is also described in Peter Galie’s Ordered Liberty: A Constitutional History of New York and in my book, The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History.

Hastily-organized elections were held in the spring and summer and the first legislature assembled in Kingston in September 1777 and got to work. The fledgling government had to flee as British troops assaulted and burned Kingston on October 16. It soon re-assembled in Poughkeepsie and resumed work. By then, patriot forces had defeated British incursions from the west (at Oriskany) and the north (at Saratoga) and a minor incursion from the east (at Bennington).

New York State was here to stay.

Why should New Yorkers (and people beyond New York) be interested in the state’s birthday and its critical origin and survival year of 1777?

Several reasons:

It is a key part of an inspiring against-the-odds story of determination and resilience. In early 1777, it was by no means certain that the rebellious colony of New York would survive and achieve independence along with a dozen other colonies. By the end of the year, New York had written a constitution, established a government, held elections, fended off invasions from three directions, and survived invasion and destruction of its capital.

It was unprecedented. The writers had some British and other European precedents, New York’s own experience, and political philosophers to draw on. But there was no such thing as a “state” when they began. Other rebellious colonies were still writing their own independence documents. The Articles of Confederation, creating a government framework to link the new states together, would not be created until later in 1777.

It represented compromise and consensus. The writers had a number of disagreements and varying viewpoints and perspectives going into the process. But along the way they put aside their differences, compromised, and came together to develop a consensus document. That process is worthy of study now, when too often it seems difficult to reach agreement on divisive political issues.

It was concise. At about 5,000 words, it also included the Declaration of Independence as a preface. It outlined the powers of a two-house legislature (similar to what we still have today) and the governor (also similar in some ways to what we have now), provided for a secret ballot, and endorsed freedom of religion. There was a placeholder for the judiciary; that had to be fleshed out by the first legislature.

It was successful, flexible, and enduring. The first constitution proved to be a viable framework for years when New York grew remarkably fast. It endured without major changes until 1821. Even then, the structural changes were relatively modest. The new constitution streamlined the process for appointing state officials and strengthened the governor’s veto power.

It left important work undone. The convention discussed abolishing the horrible practice of slavery but in the end did not. That had to await legislation in 1799 and 1817. It included restrictions on voting rights for men, which were gradually eased over ensuing decades, and denied women the right to vote, not rectified in New York until 1917. The constitution had no bill of rights other than protection of freedom of religion. The legislature enacted a bill of rights in 1787 and they were embodied in the 1821 constitutional revision.

It was influential. The New York constitution includes some of the principles that were embodied in the U.S. Constitution a decade later, 1787. New York led the way in a sense. That is not surprising because New York patriot Gouverneur Morris was one of the principal writers of the New York document and a decade later, then a delegate from Pennsylvania, he was also one of the writers of the U.S. Constitution.

***

Bruce W. Dearstyne is a historian in Albany, NY. SUNY Press recently published the second edition of his book The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History and will publish his next book The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era later this year.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Resilient Public Schools are Key to Our Children’s and Our City’s Future

The future of schools in NYC (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Two years after lockdown, we’re entering a new phase of the pandemic. Mask and vaccine mandates have been rolled back across the state, and we’re eager to return to some kind of ‘normal.’ We have a new mayor and a new City Council, being tested for the first time. And we’re at a crossroads: what lessons have we learned? How can we ensure that our city is resilient, not just in the face of another health crisis or a new variant, but universally?

I’m a working mom, and I think a lot about the effect these two years have had on my eight-year-old at such a formative time. Schools were hit hard by the pandemic, with shutdowns disrupting the lives of countless students, families, teachers, principals, and others. When Mayor Adams announced that schools would reopen in January after winter break and amid the Omicron wave, I was hesitant, as I’m sure many other parents were. But I recognized the importance of in-person learning. My partner and I took all of the precautions we could to ensure our child’s health and safety at school.

In February, I faced a moment every parent dreads—my child tested positive for COVID-19 after an exposure in their 28-person classroom. We were fortunate that they were vaccinated and only had a mild case, but at this moment of recovery and renewal, we must do more to safeguard our public school students in New York City.

We also must do more to safeguard their future. It can be difficult to see beyond our current moment, trying to safely emerge from this health crisis. But I also want my child to grow up happy and healthy in New York City, and have the option to live a long life here, perhaps raise children of their own someday.

The 2022 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, released last month, makes it clear that the progression of climate change is much worse than we thought. Our window to change course is closing fast. The pandemic also highlighted the connection between climate change and public health, with clinical research linking high COVID-19 death rates to long-term exposure to climate degradation, concentrated in low-income and environmental justice communities—primarily communities of color. This is an urgent moment to determine our children’s future.

One of the lessons we’ve learned in the past two years is that resiliency means strong infrastructure. In New York, that starts with our public buildings. New York City public schools are some of the biggest public climate polluters and account for one-quarter of all city-owned buildings. We also know that proper ventilation is one of the most important ways to minimize the spread of COVID-19. And beyond covid, poor air quality not only impacts student and staff health, but it can also undermine learning by negatively affecting student attendance, comfort, and performance.

The Climate Works for All coalition has developed a plan for Green, Healthy Schools. The solution is retrofitting our public schools, starting with upgrading HVAC systems while we are still fighting this pandemic. Now is the time to take institutional measures to prevent the spread of airborne diseases and protect our kids, today and in the future. We can tackle the multiple crises our city faces by retrofitting school buildings, while also reducing emissions, enhancing air quality, creating green career jobs, and fostering resilient communities across our city.

As a city, we’ve already committed to reduce emissions from New York City’s biggest buildings—40% by 2030 and 80% by 2050—through Local Law 97, passed in 2019. This work needs to happen, and public buildings can set an example. Why not start with public schools? Climate is a personal issue, and it won’t wait for us. This is why I do this work—to build a more sustainable New York for my family and our community.

Retrofitting K-12 schools and installing solar systems will cut energy use by 50%, enhance daily life and health in public schools, and support student performance, engagement, and classroom behavior. It will also allow the city to address long-term public health disparities in Black and brown communities—the same communities ravaged by the pandemic. In Mayor Adams’ economic recovery blueprint, he pledged to invest equitably in neighborhood infrastructure, including schools. This is a great place to start. But to do it properly, there must be a baseline of funding year to year.

New York City must take on the urgency of this moment by ensuring that our public funding goes to public infrastructure. Climate Works for All proposes an annual investment of at least $1.6 billion for the next eight years, which would ensure the health and safety of our school children and make good on the promise to retrofit our buildings while creating good jobs.

I know that being in school is good for my child’s mental health, but we must take care of our kids’ long-term physical health too. Mayor Adams can demonstrate true leadership in his first term by prioritizing upgrading HVAC systems in public schools, starting with those in environmental justice communities. Investing in resiliency now will shape the city’s recovery, give us long-term protection from new variants or whatever comes next, and set an example for our climate future and for our kids.

***

Maritza Silva-Farrell is Executive Director of ALIGN NY, a climate and labor advocacy organization and a leader of the Climate Works for All coalition. On Twitter @MaritzaSf & @ALIGNny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Letter To The Editor: Papering Over Recycling Success

Paper recycling (photo: Michael Anton/NY City Department of Sanitation))

To the Editor:

The March 28, 2022 column, “For the Earth, It’s Essential New York Leaders Pass Extended Producer Responsibility,” by New York League of Conservation Voters President Julie Tighe misses the mark by urging lawmakers in Albany to pass an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy. State legislators should pursue a more deliberative approach to consider New York’s paper recycling achievements, and EPR’s potential adverse effects, rather than rush to include a one-size-fits-all policy approach, which could disrupt successful paper recycling.

The paper industry is a leader when it comes to recycling. Thanks to billions of dollars in private investments, the paper industry recycles over 50 million tons of recovered paper annually – totaling more than 1 billion tons over the past two decades. In fact, more paper by weight is recycled from municipal waste streams than plastic, glass, steel, and aluminum combined. Our industry has already committed approximately $5 billion in manufacturing investments by 2023 to continue the best use of recycled fibers in our products – that’s nearly $2.5 million per day in sustainability investments.

Our paper recovery rates have risen and stayed at or near historically high levels without regulatory intervention. For example, the recycling rate for cardboard – the paper material most likely impacted by EPR policies – is nearly 89%. In New York, almost 90% of residents have access to curbside paper recycling. These are outstanding figures EPR policies would not likely improve.

Reducing landfill waste, curbing pollution, and addressing our changing climate are critically important environmental goals. EPR could jeopardize already effective paper recycling and create additional economic challenges. EPR expenses imposed on paper producers could also risk increasing costs on everyday items for consumers, and impact our industry’s 28,000 New York employees, who work in 224 facilities across the Empire State – jobs that meet $1.69 billion in annual payroll and generate $211 million in estimated state and local taxes.

Our New York paper industry and its products are part of the recycling solution. Our investments in recycling infrastructure and the wide availability of recycling programs continue to play a key role in paper recycling achievements. State representatives should use this real-world success as a road map for improving recycling rates, not impede successful paper recycling programs or create hardship for constituents.

Sincerely,

Eric Steiner

Vice President of Government Affairs, American Forest & Paper Association (AF&PA)

On Twitter @ForestandPaper

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Food for Thought: Healthy School Meals are a No-Brainer

The Mayor & Chancellor at School (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

When Mayor Adams launched his campaign to improve school nutrition, he opened the door to solving a devastating and long-neglected issue that has left generations of New York City students without the fuel they need to get through the day.

We’ve all seen photos of disappointing school lunches over the years — the same sloppy joe’s, wilted veggies, and lukewarm pizza that generations of New York City students have sadly grown up on for decades. The truth is that these meals aren’t just unappealing, they’re downright harmful to students. Research shows that children whose diets lack fruits, vegetables, healthy proteins and other key nutrients have lower grades and higher rates of absenteeism.

The status quo is failing our kids. It’s time we address the child nutrition crisis head-on. We can turn this moment into a movement that prioritizes the health of our city’s youth — starting with the food on their lunch trays.

In a city where one in three children are food insecure, the hard truth is that schools are often the only thing standing in the way of hunger for hundreds of thousands of kids. Children depend on school cafeterias and lunch hours to stay nourished - especially those from historically marginalized communities, with Black and Hispanic children almost twice as likely to live in a food insecure home in comparison to their white classmates.

The depths of this crisis were never more apparent than during the height of the pandemic, when schools went remote, yet kept their doors open as food pantries serving millions of meals to students. The incredible mobilization of our schools was inspiring, while also revealing. It demonstrated how deep food insecurity runs through our communities, and how much more we must do to ensure students get the nutrition they need to learn and grow.

The reality is that food insecurity isn’t just about access to food, it’s about access to nutritious and delicious food that allows people to live healthy and active lives. The research couldn’t be clearer: healthy students have better outcomes, academically, physically, and cognitively. Of course, New Yorkers all recognize that kids deserve healthy meals, but with an issue this systemic, how do we address it?

It begins with a recognition that every part of the culinary process is critical when it comes to nutrition – from the farm all the way to the kitchen. It’s obvious that our students need more fresh veggies, fruits, and healthy proteins, but these foods have to taste good for them to have an impact. A salad means very little if it’s left half-eaten and supplanted by a bag of chips. But that’s exactly what’s happened for years at schools across the city that have relied on expensive third-party food vendors that simply aren’t getting the job done for students and families. To solve this crisis, schools can go straight to the source.

Look no further than what has been accomplished by KIPP NYC College Prep High School, a public charter school in the Bronx, for example. For years, our school, like so many others, relied on an outside catering company that provided pre-made and uninspired lunches for students. We realized we could do better if we took nutrition into our own hands - and so we did. Today, we source and cook our own fresh ingredients and offer vegetarian and vegan lunch options every single day, all cooked by our very own culinary team, including student and alumni workers who are passionate about the culinary arts.

The results of this initiative have been nothing short of remarkable. Students are actually excited to eat their school lunches, and teachers are reporting that students are more alert and attentive in class. What started as a culinary club has expanded to a full-blown nutrition program at seven schools, serving thousands of students with sustainable in-house breakfast, lunch, and snacks every day, and a goal of soon serving all 10,000 of our students, including those sharing buildings with district schools.

Students across New York City depend on schools to nourish their minds and their bodies, and no matter what type of school they attend, they deserve nothing less. Today, schools across the city are innovating to provide better food and nutrition to their students, and in the spirit of Mayor Adams’ own words, when we see excellence, we need to scale it up.

The mayor and Schools Chancellor Banks have gotten the conversation started, but it will take all of us to fix the broken school nutrition system and provide students with the healthy, delicious food they deserve. We can do it one school meal at a time.

***

Mike Ioli is Senior Director of KIPP NYC’s Culinary Team.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.