DACA at 10: My American Journey and the Work Ahead for Others

A naturalization ceremony (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Ten years ago, the Obama administration announced that people who came to the United States without documentation as children could apply for basic protection on their immigration status. Since then, hundreds of thousands of people have received Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), including an estimated 30,000 DACA recipients in New York City. Without DACA, these young people would be stuck on the margins of American life as undocumented immigrants. I know, because I’m one of them.

On my 12th birthday I awoke before dawn and gathered my belongings. The streets of my home town in central Mexico were quiet as my mom walked with me. My uncle and I left that day to join my father in New York City. As we walked, my grandfather greeted us. He bid me farewell, and it was the last time I ever saw him.

The journey took two weeks. I was nearly kidnapped in the Arizona desert when we crossed the border in the dark of night. For a young child, it was a harrowing experience, compounded by the culture shock of a crowded South Bronx apartment and enrolling in middle school without speaking any English.

Amid the hardships I was still able to make progress. My dad signed me up for extra classes and took English lessons with me on weekends. Working long hours in construction, he put me through college, and I graduated at the top of my class.

Despite that success, I was still an outsider. I was a young college graduate with hopes and ambition. But on paper, I was nobody. Most employers wouldn’t hire me. I couldn’t get a driver’s license or a passport. I could not visit my mom and family in Mexico. Any small mishap could lead to arrest and deportation.

Then DACA was created in 2012. When my application was approved, everything changed. I said “I’m a human here in this country now; I didn’t feel like I was before.” The New York Times printed the quote.

As a DACA recipient, I have been able to do things I could only dream of before the policy was introduced. I earned a Master of Public Administration degree and worked in government helping people access the same services that I was once denied. Eventually I became a U.S. citizen and in 2020 I voted to elect a president of the country I call home. Most importantly, I was able to visit my family in Mexico after 15 years away and spent time with my remaining grandparents in their last days.

Looking Ahead

Democrats in Congress pledged to rebuild a better future for all communities. Despite this, immigrant communities have yet to see substantial action as the Biden Administration is now in its second year in office.

President Biden ran on the promise of a more humanitarian immigration system. He ran on a platform of opposing Trump's actions, establishing our asylum system, protecting and expanding DACA and TPS, and offering a road to citizenship for 11 million undocumented immigrants. President Biden has deported and expelled nearly 1.8 million people in his first year in office, despite his vows to safeguard immigrant communities and end deportations.

Across the country, millions of undocumented immigrants face imprisonment and deportation without a path to citizenship, many of whom have risked their lives as essential workers to keep us safe, nourished, and healthy throughout this pandemic. With deportations and expulsions on the rise under the Biden administration, President Biden must choose between helping Americans and providing a path to citizenship or leaving millions susceptible to the Department of Homeland Security.

For hundreds of thousands of people like me, DACA changed our lives for the better. It gave us a voice. It provided a bright path forward for us after years in the shadows. It recognized our potential to make a difference in this country, and we have. But still there are millions more undocumented immigrants who have been left behind. They need a path forward too. With positive, innovative policies like DACA, there is no telling what opportunities might lie ahead.

***

Luis Rey Ramirez is a Mexican-American immigrant from Queens. He is an active public servant, artist, designer, and videographer with experience as a leader in the nonprofit sector and supporting state and local government, and a champion for LGBT issues.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

FDA Not Aggressive Enough as Multiple New York Baby Food Companies Tainted with Heavy Metals

Baby food (photo: @kgregory)

On February 4, 2021, a congressional report exposed four major baby food companies for allowing tremendous concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury in their products. Naturally, shortly after finding out about the sheer carelessness of the manufacturers, parents nationwide became outraged and began filing lawsuits against the responsible companies.

Among the most recent lawsuits, there is one concerning HolleUSA, a European baby food company founded in 1934. This manufacturer's products are sold in the United States by Jet Set Go Baby, headquartered in New York City. As is the case of multiple other baby food companies, the class-action lawsuit alleges several products by HolleUSA are contaminated with dangerous heavy metals.

At the request of the New York State Attorney General's Office, Brooks Applied Labs tested 18 samples of HolleUSA's products in December of last year for the presence of heavy metals. The lawsuit states that all 18 baby food samples had "varying high levels" of heavy metals. "Not a single sample from Defendant did not contain heavy metals," the case states. The lawsuit accuses the company of "deceptive representations and omissions" for products such as Holle Goat Milk Toddler Drink and Holle Organic Panda Peach, Fruit & Grain Puree.

Three Other New York Based Baby Food Companies Disregard the Safe Limits for Heavy Metals

Three companies whose baby food was found contaminated with mind-blowing concentrations of heavy metals by the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Economic and Consumer Policy are also headquartered in New York – Beech-Nut, Hain Celestial Group, and Nurture. However, once Beech-Nut issued a recall on one lot of Beech-Nut Stage 1, Single Grain Rice Cereal, it also exited the baby food market. The baby food company used to have its headquarters in Amsterdam, New York, and one of the most disturbing findings is that it used ingredients with over 900 parts per billion (ppb) arsenic, while the safe limit is 10 ppb.

Another baby food company that agreed to participate in the congressional investigation, Hain Celestial Group, is headquartered in Lake Success, New York. It sells baby food under the brand name Earth's Best Organic and was discovered to allow products containing 352 ppb lead to go on the shelves when the maximum limit is 5 ppb. Nurture also has its headquarters in New York. According to the congressional report, this baby food company, which sells products under the brand name HappyBABY, used ingredients with 641 ppb lead.

Exposure to Heavy Metals and Child Development

Exposure to such enormous concentrations of heavy metals from infancy is associated with a risk of autism, among other neurodevelopmental disorders and problems. Once inside developing children's bodies, arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury act as neurotoxins, wreaking havoc on their brain and nervous system. Children are more vulnerable to experiencing the negative health effects of exposure to heavy metals because they have a greater nutrient uptake rate by the gastrointestinal tract and underdeveloped detoxification systems.

Since 2007, the incidence of autism has increased by roughly 1%, and 1 in 44 children born in or after 2010 will develop the disorder. Exposure to heavy metals from a young age is also linked to cognitive damage, a lower IQ, behavioral abnormalities, ADHD, learning disabilities, and speech, hearing, and visual impairment. New York ranks third among states with the highest special education rates, with 17.3% of children enrolled in special education.

The FDA’s Closer to Zero Plan, Not Radical Enough

Soon after the Subcommittee on Economic and Consumer Policy made available the congressional report, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) came up with the Closer to Zero plan, which is meant to "reduce exposure to arsenic, lead, cadmium, and mercury from foods eaten by babies and young children to as low as possible." Nevertheless, the agency's strategy is quite problematic and has numerous shortcomings. Perhaps the most frustrating thing about the Closer to Zero plan is that it would be finalized in 2024 or later, in the context in which infants and toddlers urgently need clean, non-toxic food.

The Closer to Zero plan has four steps, out of which the first two – "evaluating the scientific basis for action levels" and "proposing action levels" – can be skipped. The FDA already knows the safe limits for the four heavy metals from the Baby Food Safety Act of 2021. The bill was proposed on March 25, 2021, by Congressman Raja Krishnamoorthi. It will immediately set maximum limits for arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury in baby food throughout the United States if it becomes law.

Only the third step of the Closer to Zero plan yields some worthwhile action – assessing the achievability and feasibility of the action levels. The FDA should make sure all baby food manufacturers across the country have the means to implement measures that minimize the content of heavy metals in their products, such as sourcing their raw ingredients from crops grown on soil with a low arsenic content and using food strains that are less likely to absorb heavy metals.

Other notable shortcomings of this strategy include failing to consider the cumulative impact of heavy metals on children's neurodevelopment and not being consistent in making parents aware that there is no safe lead concentration in children's blood. Many people, as well as authorities, are discontent with the Closer to Zero plan. On October 21, 2021, 24 Attorneys General petitioned the FDA to prioritize establishing safe limits for heavy metals in baby food. They also expressed their dissatisfaction with how the agency is tackling the problem, saying that the FDA should take more aggressive measures.

The Baby Food Safety Act of 2021 - A Glimpse of Hope for Parents

The Baby Food Safety Act of 2021 would be a much more effective and viable alternative to the Closer to Zero plan, as the safe limits for heavy metals would become effective immediately, and it would also make it mandatory for the FDA to become more involved in supervising the baby food industry. This bill would also oblige facilities that handle baby food to have controls and plans to ensure their products comply with the safe limits on heavy metals. Finally, the Baby Food Safety Act of 2021 would have the Centers for Disease Control lead awareness campaigns on the risks of heavy metals in baby food.

***

Jonathan Sharp is Chief Financial Officer at Environmental Litigation Group, P.C., Headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama. The law firm specializes in toxic exposure and represents clients across numerous other mass torts nationwide. On Twitter @ELGBirmingham.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York's Democracy is Broken; Albany Leaders are to Blame

Lonely voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Our federal democracy is broken.

The Supreme Court is poised to overturn Roe v. Wade; five of nine justices were nominated by presidents who lost the national popular vote. Those justices have thrown their hands up when asked to address extreme partisan gerrymandering, then used their pens to gut what’s left of the Voting Rights Act.

Gerrymandering locks in minority power nationwide while the filibuster does the job in the Senate, so widely popular policies like universal background checks for gun purchases are left undone.

As we look to Albany to shore up abortion access and gun control, our blue bastion should also be a national model for a healthy democracy. But — traceable directly to a lack of pro-democracy energy in our State Legislature — New York is anything but.

Our failure to deliver fair, inclusive, well-run elections makes us a national laggard at the very moment we must be leading, and the consequences are far more than embarrassment. Our impoverished democracy disenfranchises voters and reduces the responsiveness of our legislators to the oversight of New Yorkers.

First, there is the fiasco surrounding the tossed-and-redrawn Congressional and State Senate district maps and choice to hold two primary days, a court-ordered August primary for those races and a June primary for Assembly, statewide, and other races. Good government groups affirm that the split primary will disenfranchise voters beyond our already dismally low turnout, a boon to incumbents but a loss to New Yorkers. State leaders chose not to consolidate the primaries in August though they had time to do so after the court order.

The hydra-headed debacle was all of Albany leaders’ own making. Beyond drawing the maps that have been ruled unconstitutional, they’re responsible for the state’s top court being led by a bloc far more conservative than the state is.

Chief Judge Janet DiFiore is a former Republican appointed by then-Governor Andrew Cuomo. She wrote the decision after the 4-3 ruling against the Democratic district maps, which got its decisive vote from Madeline Singas — a conservative Democrat who Cuomo pushed through. All but ten Democratic state senators voted to confirm her over progressives’ objections to her record; with the redistricting decision, those Democrats’ neglect of the courts came home to roost.

But legislators’ anti-democratic actions aren’t limited to making the courts their Lucy with the football of cushy districts. The coming split primaries will happen within a status quo of anti-voter laws and unprofessional administration, thanks to both past negligence and current disregard from legislators.

Last year, Democrats did nothing to support the passage of constitutional amendments to enable same-day voter registration and no-excuse absentee voting in New York — critical, common-sense, pro-voter laws that exist all over the country to drive more turnout. Republicans spent money and campaigned against the changes; in spite of Democrats’ 2-to-1 voter registration advantage, the amendments failed by double digits.

The 2021 election was the latest in a long line of failures of election administration in New York, and in particular New York City. Our Board of Elections fumbled the first tabulation of ranked-choice voting results — undermining confidence in the vote at a moment when flames of the Big Lie are fanned by any lapse in election integrity — after having to replace 100,000 absentee ballots during a mishap in 2020. And the list goes on.

Since then, State Senator Liz Krueger has been seeking to professionalize the New York City Board of Elections, but the bill to do so didn’t pass during the just-ended legislative session; it lacked support in the Assembly after passing the Senate.

The session wasn’t all bad. The hard-won John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act of New York will serve as a bulwark against discrimination and voter intimidation. On the other hand, a bill to move more municipal elections to even-numbered years to boost turnout failed.

Albany insiders — and especially the Assembly’s establishment, status-quo-biased incumbents — have little incentive to significantly improve elections and boost turnout in New York. Better turnout, and a more informed electorate, might upset their Big Applecart.

The Assembly’s undermining of democracy isn’t limited to which bills it won’t advance — it’s also reflected in a lack of transparency. Speaker Carl Heastie has restricted media access and limited public observation of the chamber’s proceedings, and his conference hasn’t forced more openness or accessibility.

The picture is dire, and a desiccated democracy isn’t the only consequence of the anti-democratic interests of our Assembly members. Ever since the 2018 election swept new insurgents into the State Senate — ousting the IDC Democrats who gave Republicans control of the chamber — good laws stall in the Assembly, where there is no significant coalition pressuring leadership to step off the beaten path.

Facing a further entrenchment of minoritarian power in Washington, we must demand more from our own legislators. If we want our federal representatives to kill the filibuster, expand the court, codify abortion and voting rights, and more, we must also make bold demands of our state elected officials: draw better districts, appoint better judges, build better courts and elections, advocate better pro-voter laws, and demand better from legislative leadership.

New York deserves more from Democrats in Albany, and American democracy needs more from New York.

***

Ryder Kessler led voter protection teams for Democrats during the 2020 presidential election and 2021 Georgia senate runoffs. He is now a candidate for State Assembly in District 66. On Twitter @ryderkessler.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Our Path to a Safer New York City Runs Through Affordable Housing and Small Businesses

Open for business (photo: Benny Polatseck/Mayoral Photography Office)

Our city has seen better days. You can’t walk a block in Chelsea without feeling like you’re in a graveyard of small businesses — I count six vacant storefronts on my block alone. The streets feel far less safe than they used to — a fight recently broke out next to my wife and me as we exited a coffee shop on 8th Avenue. And every day it feels like there’s more and more trash — everywhere.

In fact, these individual issues are all part of an underlying cycle of reduced street vibrancy that threatens to stick with us beyond the pandemic. Remote work began a process whereby reduced foot traffic in Midtown and the surrounding neighborhoods like Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen led to vacant storefronts and undisturbed piles of trash, which led to reduced street safety, which led to further reductions in foot traffic. And on the cycle goes — unless we act.

Fortunately, the Adams administration recognizes this issue of vibrancy. Unfortunately, too large a portion of its attention is directed at forcing a return to work and at a nightlife-focused campaign to “let the city dance.” (Though I should note that I am supportive of some of the less attention-grabbing initiatives introduced by the mayor, such as proposals to make it easier for homeowners to create new rental units without additional parking requirements and for business owners to expand in their current locations.)

The core issue for communities in the middle of Manhattan is to restore vibrancy by building more livable neighborhoods for residents. The policy prescriptions aren’t easy, but they are achievable if we take three steps: First, we must increase foot traffic throughout workdays, weekday nights, and weekends by making New York’s housing affordable to a diverse array of residents, including young families; second, we need to tackle street safety head-on; and third, we have to fill in storefronts by disincentivizing landlords from accepting long-term vacancies and providing creative solutions to vacant space.

It starts with housing: unless it is possible for people to afford to live in our neighborhoods, then they cannot be livable. An innovative and progressive approach to fixing our housing crisis begins with passage of the Good Cause Eviction state bill that would cap rent increases and give tenants more power in negotiating their lease renewals. In the medium term, the state must continue increasing the supply of affordable housing to bring down prices, doubling down on efforts to convert unused office spaces and hotels into housing. Lastly, we should be on the search for the space and funding to build the next-generation Penn South or Manhattan Plaza — and ensure we remember the importance of those beacons of affordability.

Assuming reduced housing costs make it possible for people to live here, then the challenge becomes ensuring that people want to live here. And people want to live where the streets feel safe and dynamic. Today, homelessness has reached a crisis level, and our homeless neighbors are making an arguably, and sadly, rational choice to stay out of the unsafe shelter system. That must change, via significant investment in social services and job training to help homeless New Yorkers get on their feet.

It’s also critically important we take bold steps to keep guns off our streets; just last week, gunshots were fired near a Chelsea school, though thankfully no one was harmed. I applaud Governor Hochul and Democratic legislators for acting swiftly to strengthen “red flag” laws and raise the age for purchasing an assault rifle. We must do everything we can to stop gun violence and the pipeline of out-of-state guns that flood our streets. The safety of our neighborhood depends on it.

And finally, we arrive at solving the problem of vacant storefronts. Proposals like Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal’s bill to tax landlords for long-term vacant storefronts are a great start. Landlords should pay for the harm that they incur on neighborhoods when they leave commercial spaces vacant in the long-run by holding out for rents that are too high.

But let’s build off of this bill and ensure that we achieve the purpose of filling in our storefronts while retaining economic viability for mom-and-pop property owners: we can provide those same landlords with the opportunity to waive the vacancy tax if they allow organizations like ChaShaMa to temporarily use the space for free as a “pop-up” art gallery or performance space. Every empty storefront is an opportunity to revitalize our streets, bring in small businesses, and find a mutually beneficial arrangement for the community and its landlords.

We can’t sugarcoat it: the city is in a tough spot. But we have an opportunity right now to change an undesirable “new normal” before it solidifies. Let’s stop begging workers to return to offices and let’s start making New York a place that everyone wants to live in again, including its current residents.

***

Harrison Marks worked in the Office of Management and Budget in the Obama Administration and lives with his wife and son in Chelsea. He is a Democratic candidate for the 75th Assembly District. On Twitter @HarrisonDMarks.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

It’s Time to Reform New York’s Judicial Selection Process

Judicial oath of office (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

I recently wrote an op-ed on the need to raise public awareness about judicial selection, inspired by the leak of the Supreme Court draft opinion in Dobbs that would reverse Roe and the recognition of women’s reproductive autonomy. As a candidate for Surrogate’s Court Judge, I have been frequently asked about the judicial selection process and hope to advance an open dialogue on judicial reform, independence and the importance of voter awareness.

Anecdotally, according to my own recent informal Twitter poll, a plurality prefers that judges are elected as opposed to appointed, or a combination thereof. But New Yorkers clearly need a better understanding of the process.

Judicial selection methods in New York State can be particularly baffling. Some judges are appointed (by the Mayor or Governor), some are elected, and some are “elected” without direct voter participation.

For example, candidates for state Supreme Court judge appear on the ballot through a process that is little known and poorly understood by most people. New York's Election Law (§ 6-124) created an alternate method to the petitioning process. In place of a primary election, judicial delegates (who are elected during the Democratic primary) vote at a judicial nominating convention (usually in late summer) for the Democratic Party candidates who will appear on the general election ballot. This process not only deprives the voting public the opportunity to directly participate, but it can be fraught with issues of conventional party politics; namely who’s in the know and in control.

In contrast, judicial candidates for other positions must petition for a specified number of signatures from registered voters of their party to appear on the primary ballot. I am running for Manhattan’s Surrogate’s Court, also known as probate court, the court that oversees wills and estates, as well as the appointment of fiduciaries, guardianships, and adoptions. For a countywide side seat, I was required to obtain 4,000 signatures from registered Democrats to appear on the primary ballot. However, as a practical matter, a candidate must obtain triple the number of required signatures to withstand a potential challenge by a competitor. The process is made arduous because of the limited time frame to obtain signatures (about a month).

Judicial candidates for Civil Court positions also need signatures (1,500) to appear on the primary ballot, a threshold significantly higher than required in races for Congress (1,250), State Senate (900), State Assembly (500) and City Council (450).

An additional incongruity is that Civil Court districts - established in 1962 by state law - are not subject to redistricting laws or the federal Voting Rights Act, so their lines remain static notwithstanding population shifts. Despite the recent focus in New York on gerrymandering and the fairness of districts, judicial lines were absent from the discussion.

In Manhattan, district leaders (or “state committee members”), also elected but with few specified legal duties, play a significant role in the promotion of judicial candidates. It’s a lot to ask of voters to find information on these less commonly known seats (judicial delegates, and state and county committee leaders), and research their stance on the judiciary prior to primary day. However, until the system is reformed, these positions continue to play an outsized part in the outcome of judicial races, and voters should at least understand that judicial selection depends on the role these “go-betweens” serve.This is particularly the case as voters rely on the independence of the judiciary, whose impactful decisions are felt first-hand by the electorate.

We need real electoral reform in judicial elections.

Some suggestions include a reduction in the number of required nominating signatures, a cap on the amount that can be spent on judicial races (with strict donation limits), and a re-examination of the function of judicial delegates, district leaders, and judicial districts that have witnessed population shifts.

There is nothing wrong with voters choosing who their judges are. The problem is that voters lack the information necessary to make informed choices. In a society always striving for improvement and reform, the judicial selection process should not be last in line.

***

Elba Rose Galvan is a Surrogate's Court Referee in King's County and candidate for Manhattan Surrogate. She served under Surrogate Margarita Lopes Torrez, and currently serves under Surrogate Rosemarie Montalbano, both considered reformers of the court.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As Albany Continues to Abandon Homeless New Yorkers, California Considers New Solutions

Health and housing are tied (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

As roughly 50,000 men, women and children sleep in a New York City homeless shelter each night and the number of people living unsheltered on the streets and subways has increased, the powers that be in Albany bear a large portion of the responsibility for the current state of affairs. It is time that we take a long hard look at what state government has done in this regard instead of putting all the blame on City Hall.

According to the very comprehensive State of the Homeless report published annually by the Coalition for the Homeless, the state government continues, as it has for many years, to receive failing grades on almost every metric. With regard to meeting the needs of unsheltered New Yorkers, New York State received a failing grade on five of the six metrics and a “D-” on the other one. In addition it received similar grades on the operation of the shelter system, housing, and institutional discharge planning.

On this last category, each year since 2015 more than 40% of people released from state prisons to New York City were released directly to shelters. This amounted to an average of about 3,500 a year. As Gotham Gazette recently reported, little is being done to help those leaving prison find stable housing, and so many wind up going directly into the shelter system, with some then leaving for the streets.

The homelessness crisis is being seen more and more as a mental health crisis, which it is in part, and once again New York State bears a heavy responsibility for what we now see. The state psychiatric center system that once served 93,000 New Yorkers has now dwindled to an insufficient 2,330 beds.

Meanwhile, nothing paints a better picture of how state government has abandoned homeless New Yorkers than how the shelters are funded. As the cost of New York City Department of Homeless Services shelters rose by nearly $1.2 billion between fiscal years 2011 and 2021, the city was left to pick up 95% of the increase for single adult shelters and 32% of the increase for family shelters. While the state covered a mere 4% of the additional cost for single adult shelters and 7% for family shelters.

The new state budget is somewhat better but far from acceptable. Lawmakers passed a budget that does little to house homeless New Yorkers, according to exasperated advocates and policymakers. “It’s pretty dreadful,” said Legal Aid Society Supervising Attorney Judith Goldiner.

During protracted negotiations, the governor and legislators axed a proposed Section 8-style rent subsidy for New Yorkers experiencing or at-risk of homelessness. Governor Kathy Hochul and her budget team said it was too expensive.

While New York City and State are facing this monumental task of substantially reducing homelessness they must be equal partners. In California, which is also facing a homelessness crisis, a new approach has emerged.

California has a new plan to get people off the streets and into treatment. CARE (Community Assistance Recovery and Empowerment) Courts connect a person in crisis with a court-ordered Care Plan for up to 12 months, with the possibility to extend for an additional 12 months. The framework provides individuals with a clinically-appropriate, community-based set of services and supports that are culturally- and linguistically-competent. This includes short-term stabilization medications, wellness and recovery supports, and connection to social services, including housing.

CARE Court is not for everyone experiencing homelessness or mental illness; rather it focuses on people with schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorders who lack medical decision-making capacity – before they get arrested and committed to a state hospital.

Although homelessness has many faces in California and New York, among the most tragic is the face of the sickest who suffer from treatable mental health conditions — this proposal aims to connect these individuals to effective treatment and support, mapping a path to long-term recovery.

CARE Court may help thousands on their journey to sustained wellness. Its engagement begins with a petition to the court from a wider range of individuals, including care providers, family members, first responders, or counties, among others. CARE Court may be an appropriate next step after a short-term involuntary hospital hold.

Having served as a Deputy Commissioner in the New York City Department of Homeless Services and as a Vice President for Supportive Housing for a nonprofit, I know it is easy to get caught up handling the day-to-day crises which arise in a system that spends more than $3 billion a year. However, we must set aside time and staff to explore the big picture as California is doing.

***

Robert Mascali is a former Deputy Commissioner at the NYC Department of Homeless Services and a former Vice President for Supportive Housing at Women in Need.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Key Investments New York City Needs to Make in CUNY This Budget

CUNY graduation (photo: CUNY)

Since the start of the pandemic, CUNY students have witnessed trauma every day. They’ve mourned loved ones who died. They’ve struggled with testing and vaccine availability. They’ve borne the stress of the COVID-19 economic crisis, and braved the worst outbreaks as front-line workers to help their families survive.

Unsurprisingly, CUNY’s enrollment declined beginning in March 2020. It’s struggled to rebound, especially at the community colleges where many students come to campus from the neighborhoods hardest hit by COVID-19.

Community college students have always struggled to balance life and a life-changing education. Community colleges around the country face the persistent challenge of retaining students through to graduation. With the increased attention on enrollment this year, now is the time to move toward a solution by investing in the wraparound services that make it possible for CUNY students to return to and stay on campus.

City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams’ recently announced CUNY Reconnect Initiative wisely offers the funding needed to support the services we know work to ensure students remain enrolled and engaged. The initiative would invest $23 million in CUNY and should be supported by the Mayor and full City Council in this year’s budget negotiations.

According to the Center for an Urban Future, there are nearly 700,000 working-age New Yorkers with some college credits but no degree. As a result, the jobs that create a pathway out of poverty and sustain families are often beyond their reach. On average, Americans with college degrees earn 65% more income per week than workers without degrees. CUNY Reconnect would help give working age New Yorkers with some college credits another chance at a great education.

The program emphasizes the need for increased services to help struggling students navigate the college environment. A similar program in Tennessee invested in child care, pre-enrollment counseling, and other services. CUNY is poised to provide such support. But the proposed investment is only a start.

The Speaker’s initial request for $23 million is a laudable beginning but we must go further. CUNY Reconnect can work, while serving existing students, if we make additional investments in the services that are proven to boost graduation and retention rates. One such service is ASAP, the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs Initiative.

ASAP is known as the most successful program at CUNY’s community colleges and modeled around the country in part because it gives students access to a dedicated advisor from enrollment to graduation. Multiple studies show that improved advising increases graduation rates. More funding must be included to increase access to academic advising at CUNY.

Since COVID-19, the increased need for advisors has created an unprecedented backlog. As Academic Advising Director in the Department of Africana Studies at John Jay, I saw the huge increase in numbers of students that needed guidance as we switched back from virtual to in-person learning. And now I see the urgent need for more thorough advisement among students returning to their studies after taking a break during the pandemic. An astonishing 44% of CUNY students are first-generation college students. They depend on advisors to help them navigate a system that can seem byzantine to an outsider. When acclimating to the new and unfamiliar space of college, advisors are their lifeline.

CUNY advisors want to help, but we’re struggling. At a recent union gathering one advisor called the student-to-advisor ratio “mental and emotional murder.” Another noted that “it’s very difficult to do case management because those caseloads are so high… [we are] losing staff members. We are all exhausted.” The current situation is not sustainable and doesn’t give our students what they deserve.

We can do better. CUNY is a public service and a wise investment. In this year’s budget, the City must step up for its people. This year’s New York City budget must expand funding for advising CUNY-wide so that all students can receive the level of high-contact individual attention offered via ASAP. And for good reason: the three-year graduation rate for ASAP students is more than double that of non-ASAP associate degree students at CUNY’s community colleges and it narrows graduation gaps for Black and Hispanic males. A move toward ASAP for All is a $20 million investment that would provide more students with the advisor they deserve.

CUNY students want to graduate, taking their new skills and diploma into the next stage of their lives. The City wants that too. It can’t happen without the wrap-around services students need to navigate college.

***

Rulisa Galloway-Perry is Academic Advising Director and Administrator at John Jay College.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Suburbs Need to Finally Step Up in New York Housing Crisis

Housing in view (photo: Governor's Office)

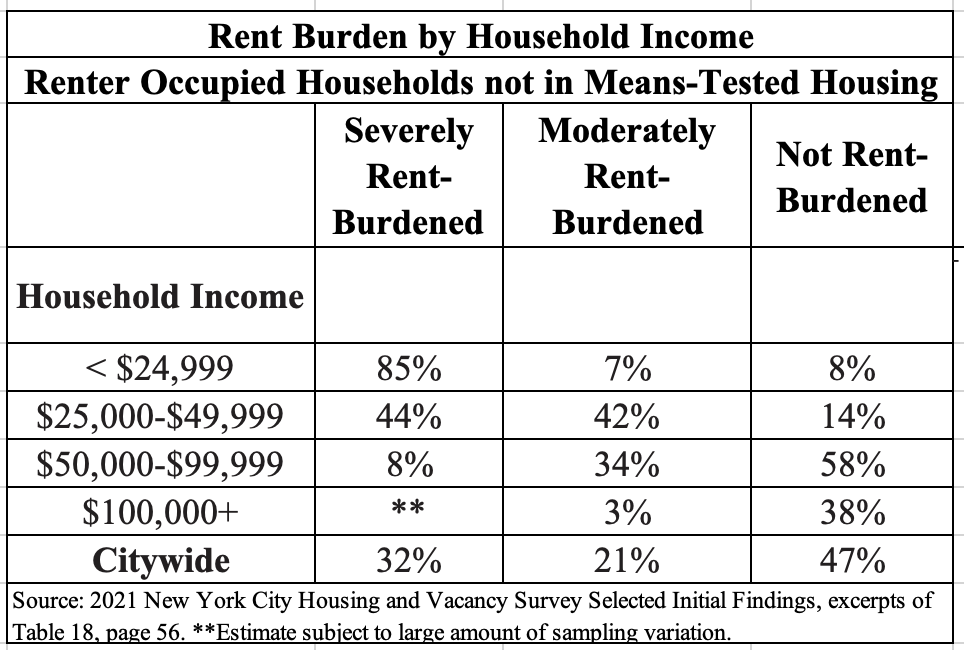

It is easy to focus on New York City proper when thinking about the affordable housing crisis. Initial findings from the city’s triennial Housing and Vacancy Survey, for example, show that 32% of all city renters not living in means-tested housing are severely rent-burdened, meaning paying more than 50% of household income for rent. It’s 85% for households with income of less than $25,000.

But, as New York City Mayor Eric Adams prepares to release his housing plan – building on an outline of proposed citywide zoning amendments he recently presented and other elements his appointees have offered – we cannot continue to ignore the regional dimension to that crisis.

More than 50 years ago, the Regional Plan Association issued a report on housing opportunities in the New York City region, noting in 1969 that there was “growing apartheid” and a “severe limitation” in the suburbs on housing available to members of minority groups. The report further referenced the fact that there was disproportionately little affordable housing in the suburbs and that the growing apartheid system “placed a severe and unfair burden on local governments [most notably New York City] which are left with inordinate costs resulting from poverty.”

Fast-forward to the present. According to 2020 Census data, there are still in Westchester at least 16 towns and villages that have Black populations of less than 3%. Along with the racial segregation, the disproportionate costs borne by New York City as compared with its neighbors in respect to providing both affordable housing and social services remains as well.

Using 2020 five-year American Community Survey data compiled by Social Explorer, I found that only 13.1% of the combined households in Westchester, Nassau, and Suffolk had household income of less than $30,000; by comparison, the percent of New York City households with household income of less than $30,000 was 26.1%.

In other words, the percentage of New York City households defined as “extremely low income” is double that of its suburban counterparts. (At the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of suburban households with household income greater than $150,000 was 34.7%, significantly higher than the 20.1% of New York City households that met that criterion.)

So for all the ideas about what to do about affordability within New York City – including some recent ones of my own – it is important not to forget the critical role that New York’s suburbs are supposed to be playing in providing a fair share of regional affordable housing need.

Despite their acting otherwise, New York City’s suburbs are not beyond the reach of state law (which has long required that each municipality plan for its share of regional housing need). They are not supposed to be beyond the reach of federal law, either. The Fair Housing Act makes exclusionary zoning – like those suburban zoning codes that preclude the building of multiple-family, mixed-income housing – illegal.

Yet these suburbs have, for decades, defied state and federal law and failed to build much housing. From 2010 to 2020, for example, the Regional Plan Association calculates that Nassau and Suffolk Counties had fewer than 10 building permits issued per 1,000 residents, and that Westchester clocked in at only 13.5. Manhattan housing starts per 1,000 residents – inadequate still – were a much higher 30.1.

One notable recent example of the active suburban resistance to building affordable housing is found in the fate of the landmark housing desegregation consent decree that the Anti-Discrimination Center won against Westchester in a case brought under the federal False Claims Act.

The consent decree entered in the case had, according to a brief filed by several fair housing organizations, “provided more opportunity to effect significant structural change in hyper-segregated residential housing patterns than any other legal proceeding in the last 25 years.” Ultimately, though, the decree had to be enforced by the federal government and its monitors, who were unprepared to do so. They snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by failing to have the political will to overcome the county’s resistance.

Even more recently, New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed early this year what she described as “sweeping plans” to address the housing affordability crisis, including zoning changes to allow accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods and to override local limits on multi-family, transit-oriented development. These zoning initiatives quickly ran into intense suburban opposition, and were dropped from Hochul’s budget proposal.

New York’s Department of City Planning would appear to understand at least on some levels that the city’s housing needs exist within a regional context, but the city’s leadership has never done more than engage in a “pretty, please” approach to seeking regional equity (to be honest, it is not even clear whether city leadership has gone as far as “pretty, please”). The failure of New York City’s suburban neighbors to build their fair share of affordable housing not only hurts their own residents, that failure contributes significantly to New York City’s affordable housing crisis as well. And the failure of the city to press its neighbors to do more has been a grave error.

The city should open its eyes, exert real political will, and be prepared to use all the tools it has available – including state and federal legal tools that I am confident would be successful – to bring affordable-housing “fair share” to the metropolitan region.

***

Craig Gurian is executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center, based in New York City. On Twitter @antibiaslaw.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Public Health, Public Safety, and the New York City Budget

Mayor Adams at an announcement (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Typically, the scorching hot summer months bring a rise in violence, but there’s much more than temperature at play. Last fall, a Violence Interrupter in Brooklyn shared with us his greatest concerns as we moved to the colder months. He noted that the sunset of extended unemployment benefits would cause more families to be under stress, leading more kids to leave their turbulent home environment in search of solace and kinship in the streets.

It’s not complicated from his perspective.

But this simple and poignant analysis of how poverty leads to violence is rarely reflected in conversations around the city budget.

If we allow public safety to be defined in the context of policing, prosecution, and incarceration, we should not be surprised when we see our jails and courts overwhelmed. Court delays have skyrocketed since the covid pandemic and Rikers Island remains under federal monitoring. Just last month the monitor released another report detailing the mismanagement and violence faced by those detained at Rikers and by the correction officers themselves. We now spend more than half a million dollars annually per client in the Department of Correction – about five times more than in Chicago and Los Angeles – clearly more money for police and jails will not fix this problem.

No Health, No Justice

The Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island released a report last December detailing the root causes of incarceration and the various city agencies empowered to pursue prevention and community-oriented public safety initiatives. From street lights to school nutrition, from youth employment to sanitation, the city’s investments in our residents and our communities pay dividends for decades to come.

Notably, the Mayor is obligated by local law to respond to the recommendations set forth in the report, with oversight from the City Council. The Commission’s Subcommittee on Health laid out a few core principles to frame this conversation. As with our violence interrupter’s story above, the first idea is a simple one: Ensure quality health care is available in the community so the carceral system becomes the last resort for accessing health-care services.

Who could argue with that? Why isn’t this already the case? Regrettably, our reality is far from this ideal.

The Commission report describes health-care deserts, akin to the food deserts we learned about over the past decade. The same communities that are overburdened by the criminal justice system also suffer from worse physical health, mental health, substance use, and social outcomes, mainly due to a lack of access to quality care. Despite the best efforts of the city health department to highlight these disparities, and marshal appropriate resources to respond, this generational inequity persists.

The next section of the report highlights key opportunities to pursue health equity through reforms to the State Medicaid system. The state’s current plan prioritizes individuals and families impacted by the criminal legal system. Most notably, it seeks to activate 30 days of Medicaid coverage prior to release from incarceration, to allow community-based providers to engage clients before they transition back to the community. This will improve the health and stability of some of our most vulnerable residents, and will save taxpayer dollars by preventing emergency room visits and unnecessary hospitalizations.

The state is also planning to roll out hundreds of millions of dollars in opioid settlement funds in the next decade, offering us the chance to build the community substance use treatment and mental health service infrastructure that was promised in the 1970s but never fully materialized. This would mean the ability to access care, same-day, in your own community. No two-month wait list, no travel across the city or county, no wrong door – just quality accessible services including peer supports, safe stabilization spaces, and affordable medications.

These changes will arrive too late for a client we’ll call Stephanie, whose plight is all too common. Stephanie suffers from serious mental illness and when she left prison in 2016 she went to the emergency room for a psychiatric evaluation. Her parole officer threatened to send her back to prison if she did not start taking the $2,000/month prescription medications listed in her release documents. But those documents also listed an incorrect address for Stephanie, preventing her insurance coverage from activating upon her release. With proper insurance coverage, Stephanie could have returned to the same out-patient psychiatric provider she used prior to her incarceration, but she was left without access to this care. The stress of these events further complicated Stephanie’s mental illness, and she was soon admitted to the inpatient psych unit following an incident of self-harm. All because someone listed the wrong address on her paperwork.

We can help future Stephanies and the city can lead the way.

The New York City Council recently held hearings to examine Mayor Adams’ latest budget proposal, hearing from his appointed agency leaders on how they plan to serve the residents of New York City in the year ahead. City budget negotiations are now ongoing before an adopted budget is due by the end of the month.

Let’s take the lead from our sage Violence Interrupter and keep it simple. Protect, support and build up the weakest and most vulnerable among us, and we can all thrive together. That’s the New York Stephanie and the rest of us deserve.

***

Tracie Gardner serves as the Senior Vice President of Policy Advocacy at Legal Action Center. Jeffrey Coots, JD, MPH, directs the From Punishment to Public Health (P2PH) initiative at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Rise in Asian Hate is Taking a Mental Toll on New York’s Asian and Pacific Islander Community

Stop Asian Hate rally (photo: Gerardo Romo/City Council)

As doctors, we have seen the horrific impact of COVID-19, including the adverse effects of our society's socioeconomic divides, social injustices, and widespread racism during this same period. These social ills coupled with the profound health impact the pandemic has had on our nation have intensified the mental health crisis facing Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI). Xenophobia in the United States exploded in the early months of the pandemic and has shown us that what followed the onset of the pandemic was a plague of racial prejudice.

Racism, which results in mental and physical trauma, is a primary cause in the rise of mental health issues across AAPI communities.

In a recent national survey by AAPI Data and Momentive, anti-Asian hate crimes have increased during the pandemic: 1 in 6 Asian American adults reported experiencing a hate crime in 2021, up from 1 in 8 in 2020. Cities across the country are experiencing sprees of hate crimes targeting the AAPI population and other communities of color. According to preliminary analysis, reports of hate crimes skyrocketed in 2021 in more than a dozen of America's largest cities, with a record number of Asian Americans saying they were targets. In New York City, the NYPD reported a 361% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. And in a recent national poll, 71% of Asian Americans said they felt discriminated against in the U.S. today.

This disturbing increase in hate is taking a significant toll on an already troubled mental and behavioral health care approach in demographics that identify as Asian American and Pacific Islander.

We know that approximately 77% of the AAPI population speaks a language other than English at home. From a medical perspective, telephonic interpreter services are available to patients; however, many Asian patients feel uncomfortable using these services when discussing sensitive issues regarding mental health. Discussing mental health may also be considered culturally taboo within this demographic, making it even more difficult to identify symptoms and treat depression or anxiety. Additionally, roughly two-thirds of U.S. psychologists say their waitlists have gotten longer since the pandemic started. The trouble of finding a therapist or psychiatrist who understands specific AAPI cultural backgrounds adds further barriers to care.

With the rise of Asian hate and the lasting physical and emotional scars of COVID-19, we as medical professionals are charged to help care for the AAPI community in its greatest time of need.

Beyond legal and policy changes, we have the intel, tools, access, and obligation to act now to best serve our patients and communities where they are. Listening to and understanding the community's needs are at the core of what is required to deal with trauma. Physicians need more educational training that highlights overlooked medical issues in the AAPI community, including mental health, early hepatitis screenings, addictions, food insecurities, and foods unique to specific ethnic groups and their relationship to chronic diseases.

For instance, at AdvantageCare Physicians (ACPNY), we are tackling the psychosocial aspects of delivering healthcare services to the AAPI community head-on with cultural competency courses for our healthcare providers. We also formed an AAPI-based employee resource group for our staff to offer in-house insight and support.

Many of our offices are strategically located in neighborhoods with strong cultural identities and diverse needs, including sites in Flushing and Elmhurst, Queens, Crown Heights and East New York, Brooklyn, and Manhattan’s Chinatown. Co-located with centers of our partner, EmblemHealth Neighborhood Care, these locations treat community-specific health care needs, offer translations for written materials, and employ staff who mirror the local communities' language, cultural competency, and backgrounds.

We also work with local elected and public health officials and community leaders to increase awareness of the mental and physical health needs and challenges among AAPI populations.

As New York assesses measures to improve and deploy mental health initiatives, our medical community needs to ensure there is an open dialogue in the process that includes diverse voices. We also need to implement comprehensive plans to enhance clinical practices’ ability to care for all communities' unique behavioral health needs, especially during these difficult times. It is our time and responsibility to unite against racism, and the toll bigotry leaves on our communities.

***

Qian Gu, DO, is ACPNY Flushing North Medical Office Director. Raymond Xu, MD, is ACPNY Astoria Medical Office Director. Seth Resnick is ACPNY Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Department Chair. On Twitter @ACPNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

My Love for New York City

Carlina Rivera with constituents (photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

If you grew up on the Lower East Side during the ‘80s, ‘90s, or 2000s you probably remember Lucky Variety Store. Run by a Chinese family from the neighborhood, Lucky was beloved by local kids, selling backpacks, stickers, costumes, and custom nameplate belt buckles (not to mention throwing stars). When Lucky closed in 2010, a common response was “There goes the neighborhood.”

Many neighborhoods around the city have a version of this story from the last few years: an iconic business closed, years of memories gone with it, and a sinking feeling that the community you call home is changing beneath your feet. As a lifelong Lower East Sider born in Bellevue Hospital and raised on Stanton Street, I can tell you that while my neighborhood has changed, it is still very much there, because – in addition to the businesses and homes that have withstood gentrification – the community is still there. Communities, both on the Lower East Side and across New York City, are what I’ve spent my career working to strengthen and preserve – and I’ll keep doing it as the representative for New York’s new 10th Congressional District.

I spent my childhood with my mom and sister in a Section 8 apartment between Pitt and Ridge. Even as a child, I could see the neglect of our building and our neighborhood. But the families who lived there – most of them Latino or Black or Chinese, along with a smattering of Jewish and Italian residents – were deeply committed to taking care of one other.

Growing up, our building felt like a little village. Everybody knew everybody else. People kept their doors propped open as they cooked, so the hallways smelled amazing – like simmering cabbage, rice, and beans. Neighbors doled out tips on how to be more economical about this or that; if someone noticed a teenager dragging a bag of laundry down the hall, they weren’t shy about making sure the kid knew exactly how to get the wash done properly. To help save money on necessities, people pooled their money for bulk shopping trips. On Easter, my family would head to a neighbor’s to bake a box cake and celebrate together.

That feeling of community extended to life outside the building, in ways big and small.

My mom often didn’t have enough money for a Christmas tree, but that never meant that we didn’t have Christmas. My whole family would go to my great-grandmother’s apartment in the projects in Bushwick for nochebuena — which, if you know about nochebuena, you know it’s a fun night. We’d have one present for everyone, enough food for all of us, and, most importantly, the comfort that came with being together.

As a kid, I made a habit of walking down Rivington to the matzo factory Streit’s, where the bakers would hand out free pieces of fresh matzo through the windows. Like a lot of places, Streit’s is gone now, but so much of the neighborhood remains exactly as it was growing up. I love walking by the same courts where I spent 10 summers playing basketball; Hamilton Fish Park on the east side and Carmine Street Pool on the west, our go to spots for a swim and cool-off in the hot city summers; and Our Lady of Sorrows Church, with a giant Virgin Mary statue that greeted me every time I walked out of my childhood home. My grandparents lived in Brooklyn, so growing up also meant Sunday matinees at Cobble Hill Theater, bowling with our family at Melody Lanes in Sunset Park, and shopping at what was A&S and is now the Macy’s on Fulton in Downtown Brooklyn. After a day spent in Brooklyn with my grandparents I’d come home to the Lower East Side, back to the family and friends that made New York such an amazing place to grow up. I deeply miss the businesses that have closed and the people who have moved away, and I am profoundly grateful that so much of the New York of my childhood is still here today.

I can still pop into Casa Adela on Avenue C, where several generations of the same family have been serving Puerto Rican food for 46 years, with the same salsa music playing and the TV perpetually tuned to either telenovelas or NY1. Casa Adela is also in the midst of a fraught negotiation with its building. The building, which is all affordable housing, is having trouble keeping up with capital costs; meanwhile, the restaurant can’t afford a rent hike. The board wants to keep Casa Adela, a cornerstone of the Lower East Side’s Puerto Rican culture and community, but it also has to cover its expenses.

It’s an example of a type of situation that’s been playing out in the neighborhoods of the 10th congressional district and across the city, in which so many are struggling to survive in an environment that has become less and less hospitable to working people. From Sunset Park to Alphabet City, from Park Slope to the West Village, and from DUMBO to Chinatown, rents are up, local businesses are struggling, and residents aren’t sure what the future holds. As NY-10’s representative in Congress, I’ll prioritize policies that provide real opportunities for those who have served as the backbone of their communities for generations to have a sustainable future in New York.

Taking care of the New York I love, and the New York that raised me, means listening to and fighting for the communities that need help the most. That’s something that became especially clear to me while working on my first community campaign, the development of Essex Crossing in what was known as the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area – a huge swath of land by the Williamsburg Bridge that had been sitting empty for over four decades.

I came to the campaign almost by accident. After several years of working as a camp counselor and in after-school programs, I got laid off, so I had some time on my hands. Marie Christoper – my childhood building’s tenant leader, who was always dragging me and my mom to tenant association meetings, precinct meetings, community board meetings – encouraged me to volunteer at Good Old Lower East Side, a housing organization that’s been around since 1977. Through GOLES, I learned that the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area had once been occupied by tenant buildings where nearly 2,000 families lived, most of them Puerto Rican. Those residents were all displaced in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when the buildings were razed as part of Robert Moses’ “slum clearing” initiative.

I started out by testifying before the community board about the importance of ensuring that the Essex Crossing development would do the right thing by the neighborhood and the people who’d been pushed out. Eventually, I joined the community board – just in time to vote on the first step of the land use process to approve Essex Crossing. While we didn’t get everything we wanted, we did get everything that, by listening to community members, we determined was essential, including a seamless transition and affordable rents for the vendors at the Essex Street Market, a park, and affordable housing for low-income people and seniors.

Perhaps most notably, we secured a right of return for the families who’d lost their homes decades ago; people who could prove they’d lived in the demolished buildings were given priority for subsidized units in Essex Crossing. It wasn’t until I read an article about the returning tenants that I realized that my own father and aunt were among them.

There’s a great Dominican restaurant called El Castillo de Jagua that’s had the same delivery guy for 30 years – he watched me, my sister, and our friends all grow up. But because I was just around the corner, I’d always gotten pick-up. A couple years ago I came down with a cold so bad that I decided to order in. Still, when the delivery guy arrived, I felt embarrassed for not making the short trip myself. I tried to apologize but he cut me off: “I’ll bring you soup any time.”

Sure, this man was just doing his job – but he was also demonstrating the practical sense of care that has been one of the defining elements of my life in New York. It’s something that I’ve always brought to my work representing the 2nd City Council District, and I’ll bring the same thing to Congress.

The reality is that just about every Democrat in the NY-10 race has similar perspectives on major national issues such as codifying Roe v. Wade, increasing gun control, and protecting voting rights — but New Yorkers rightly expect their congressional representatives to do a lot on the local level. I have a comprehensive understanding of what it would mean to really deliver for my district, especially when it comes to the systems that New Yorkers rely on to stay afloat, like the MTA, public hospitals, and housing. The member of congress in charge of bringing back federal transit dollars for the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg Bridges, the Holland and Carey Tunnels, and the transit hubs at Atlantic Terminal and the World Trade Center needs to be someone who uses them regularly, just like the people who live in these neighborhoods.

I grew up in a community where most people weren’t able to imagine much for themselves beyond their next paycheck; I’ve lived that way myself. I want to bring as much money into the district as possible so that we can tackle the systemic inequities that prevent so many New Yorkers and communities from having the stability and resources required to create the lives they deserve.

This district is my home. It’s where I’ve experienced every major milestone in my life, from winning basketball games and celebrating graduations to meeting my husband on the community board (yes, really) and eventually spending one of our first dates walking the Brooklyn Heights promenade.

You’ll see that care reflected in everything I do in Congress. That means identifying with and advocating for the specific needs of the people of the 10th district. It also means being willing to work with people who might not reflect the same makeup of my district or share all of my views, but whose constituents face challenges similar to mine, with the goal of producing results that will benefit NY-10 over the long-term.

A common rallying cry among Latinos is the phrase “pa’lante siempre,” onward always. We say it in times of both progress and struggle, to remind ourselves that it’s our communities that get us through whatever we face — and that no matter what, we face it together.

I’m running for Congress to help build a future that every New Yorker can see themselves in, to continue delivering for the communities that raised me, and to represent this newly drawn district with homegrown pride. New Yorkers are known for our toughness, but everyone in this city knows how much we care for each other, and how much we care about our neighborhoods. My simple promise, one which has served me well in the City Council, is to care fiercely and unapologetically, to put communities and people first, and to protect the future of New York and its neighborhoods. No act of Congress can bring back Lucky Variety Store, but a devoted and determined representative can protect our neighborhoods and residents while creating a future we shape ourselves.

Onward, always. The future of the city we love is ours to build together.

***

Carlina Rivera is a Democratic candidate for Congress in NY-10 and a New York City Council Member for the 2nd Council District. On Twitter @CarlinaRivera.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.