PSC CUNY rally in Albany (photo: Emma Powell)

The faculty at the City University of New York has lost a decade. Salaries at CUNY have been frozen since the October 2010 expiration of our contract and even before that they failed to keep pace with inflation. In 2015, assistant and associate professors at the top salary step earned 92% in real terms of what they earned in 2006. Full professors at the top step did slightly better, taking home just under 96% of their 2006 salaries.

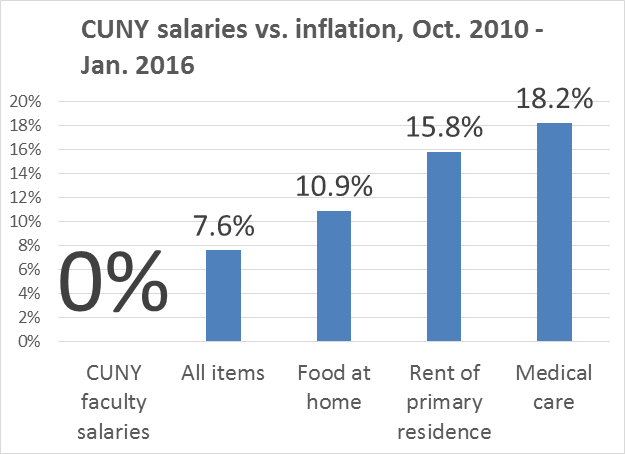

Since the contract expired, living costs in New York have risen 7.6%. Food is up 10.9%, rent 15.8%, and medical care 18.2%. Tenured full professors like me feel this on a daily basis as we struggle to balance our families’ budgets. But we’re the lucky ones.

Adjunct faculty do much of the heavy lifting at CUNY, teaching more than half of all classes, and for salaries that can be less than $3,000 per course, with little job security. In return for this paltry wage, they run classes, grade papers, and hold office hours for students. The adjuncts are the sorriest victims of the salary freeze, with many commuting frantically from one campus to another — from the Bronx to Staten Island — in an exhausting struggle to survive and to preserve a toehold in the academy and a professional identity. No wonder CUNY campuses are plastered with posters decrying “adjunct poverty.”

Students too suffer from budget cuts. Fewer courses are offered in their majors, lengthening time-to-degree. Adjuncts may not have a base at any campus and are often unavailable to meet with students or to write recommendations needed for graduate school applications. Regular faculty have to perform tasks that elsewhere are assigned to support staff, such as shopping for food for student receptions or entering course registrations in the unwieldy CUNYFirst computer. This means they have less time to advise students or to write grants that bring CUNY much-needed overhead.

CUNY has been the great equalizer, fueling upward mobility for generations of New Yorkers. Today its 24 campuses enroll 275,000 degree students and another 247,000 continuing students — some 6% of the city’s population. CUNY rightfully boasts that 40% of undergraduates were born abroad, 44% are first-generation Americans, and 42% are the first generation college students. More than half come from households earning less than $30,000 a year. Eight out of ten Latino and African-American undergraduates in the city go to CUNY schools.

CUNY remains a pillar of New York’s economy. It grants more than one-third of business degrees awarded by New York City institutions and trains one-third of the city’s teachers and many of the nurses and technicians in local hospitals. In a city where luxury condos and billionaire towers sprout like mushrooms, CUNY’s $2.7 billion capital program accounts for 20% of total construction, generating 14,000 jobs. Students at 300 high schools take courses through CUNY’s College Now program.

Why does a university that makes such an immense contribution to the city freeze its faculty pay? After five years of negotiations, management made its first salary proposal, offering three years of retroactive zero percent increases, subsequent hikes totaling 6%, and an expiration date of October 2016, a mere eight months from now. The union rejected this below-inflation “raise.”

CUNY Chancellor James Milliken and several CUNY college presidents have made tepid declarations in favor of resolving the standoff. The real obstacle is in Albany, where Governor Andrew Cuomo’s unremitting hostility to teachers’ unions extends to CUNY faculty and workers.

In 2011, Cuomo launched SUNY 2020, a program of challenge grants for capital projects and policies he argued would lead to instructional innovation and hiring at all the state’s public universities, including CUNY. The plan required that students pay $300 more each year for five years and pledged that the state wouldn’t reduce support for CUNY. Legislators voted for the hikes believing they would generate revenue to improve academic and student-support services at CUNY. Since 2012, however, the state — the source of most of CUNY’s budget — has failed to cover cost increases for rent, utilities, equipment, fringe benefits and contractual salary steps.

State revenues rose 5.6% in 2015, but in December Cuomo vetoed a bill that would have required the state to fund such increases. In January, he signed an executive action raising the minimum wage for SUNY workers to $15 an hour, but excluded state workers at CUNY. Also in January, the governor tried to shift $485 million of CUNY’s budget from the state to the city. Currently, the city funds about 30% of CUNY community colleges and the state funds CUNY senior colleges, an arrangement in place since the mid-1970s.

To Cuomo’s credit, his 2017 proposed budget includes $240 million for agreements with CUNY unions. But the $240 million is contingent on the $485 million cut in state funding. Even if the money for retroactive pay survives in the Legislature, the amount is insufficient to restore adequate salaries for faculty and other CUNY workers.

CUNY is used to crisis and austerity, with a $51 million shortfall last year and across-the-board cuts now of 3% at senior colleges. Per pupil funding is 17.4% below 2008 in inflation-adjusted terms. Top administrators’ salaries continue to climb, so the budget is balanced on the backs of faculty, workers, and students, who pay rising tuition for an education that is ever harder to deliver.

This is penny-wise and pound-foolish. CUNY’s 6,700 full-time faculty members include world-renowned experts in every field. Each year they win millions of dollars in grants, author thousands of scientific papers, and mentor new generations of informed citizens. Many depart for better jobs elsewhere. Those who remain work more years at top salary steps than they otherwise would simply to accumulate enough retirement savings. It is increasingly difficult to recruit scholars to the lowest-paid faculty in one of the country’s highest cost-of-living regions, and it is usually impossible to replace professors who leave or retire.

The neglect of CUNY exacerbates inequality, deprives hundreds of thousands of students the education they deserve, and lessens New York’s competitiveness in the global economy. New Yorkers need to decide if they want to invest in the future of their city and, if so, make sure that our elected leaders know.

***

Marc Edelman is professor of anthropology at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.