Fordham University behind the wall (photo: Brian Martindale)

New York universities are walling people out. Major private institutions across the city are surrounded by gates, but not because they are in the most dangerous neighborhoods. Rather, it appears that largely white student bodies are being walled off from their surrounding communities because of unfounded fear of racial others.

Columbia University, in a neighborhood adjacent to Central Harlem, is blockaded on every side with a security force keeping watch on all who enter its narrow gates. St. John’s University, in Queens’ Hillcrest neighborhood, is peppered with turnstiles, gated parking lots, and signs marking it as “Private Property.” Fordham University’s Rose Hill campus in the Bronx is similarly locked-down, separated from the surrounding community by wrought iron and chain link fences, at places with barbed wire and stone walls. The only way in, with few exceptions, is by scanning a school ID past a staffed security booth or full-height turnstiles.

Standing in contrast is New York University, located in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. NYU is a decidedly urban campus, built into the fabric of the city, with the public Washington Square Park serving as its primary quad.

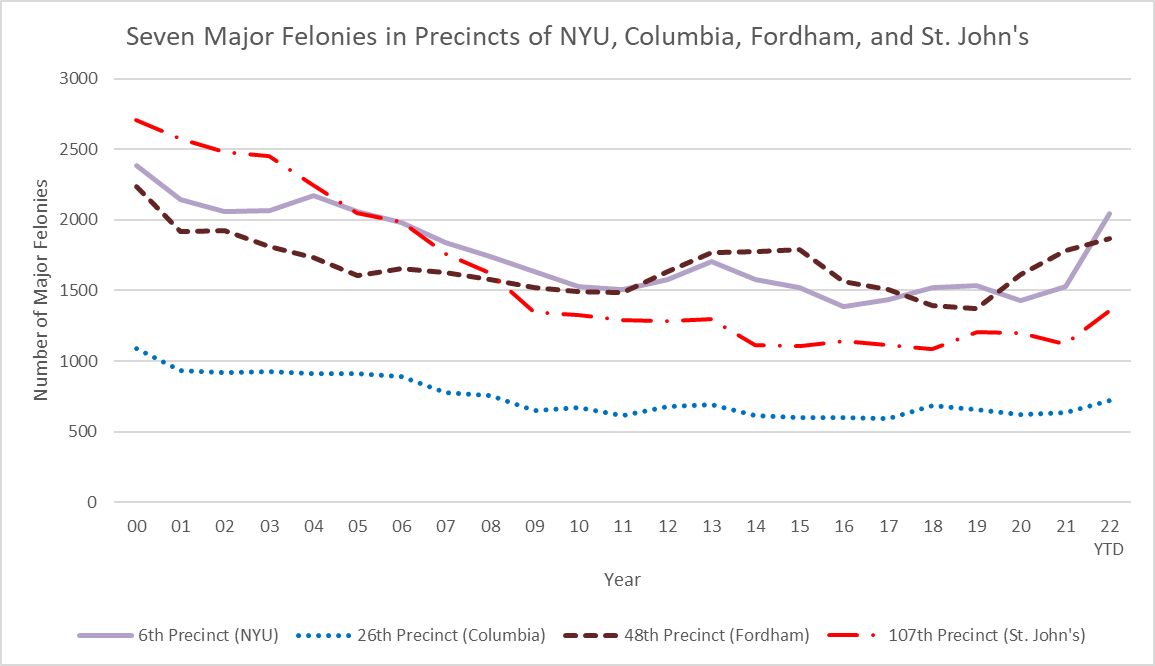

What makes NYU different? Gut instinct might suggest NYU is in a safer neighborhood so it doesn’t need a gate. But it turns out the universities that believe they need to wall out crime are actually in safer communities. A quick look at crime statistics since 2000 shows that among the four universities, NYU’s precinct has had the highest or second highest number of major felonies every year. The area around Columbia has had half as many major crimes as the area near NYU every year for the last 22. This year, NYU is on pace to have the highest crime again, with 2,045 major felonies as of November 13, compared to 1,869; 1,357; and 720 for Fordham Rose Hill, St. John’s, and Columbia, respectively. If NYU can manage without a wall, the others can as well.

There is, however, a key factor that distinguishes NYU from the three other universities: the racial makeup of the neighborhood. In 2019, Greenwich Village/Soho was 14% Black and Hispanic, while Columbia and Fordham are in neighborhoods that are majority Black and Hispanic. St. John’s is in a neighborhood that is 37% Black or Hispanic and also has a significant Asian population, at 31% of residents.

It is no secret that perceptions of safety are often related to race. A 2001 article by researchers at Florida State University suggests the presence of racial “others” lead to greater fear of crime, and another 2018 article suggests such “white fear” leads to continuing racial segregation. The universities in predominately non-white neighborhoods, though they are safer, appear to be using walls to shut out their neighbors because of this fear.

The shutting-out also shows itself in university enrollment. While 96% of Fordham’s Bronx neighborhood is Black or Hispanic, only 18% of its Bronx campus students were Black or Hispanic in 2020. Columbia had a mere 13% Black or Hispanic population at its Morningside Heights campus in 2020 compared with 52% in the neighborhood. St. John’s Queens campus is closer, with 31% Black or Hispanic students compared to 37% in the neighborhood, but Asian representation is only 16% compared with 31% of neighborhood residents.

These disparities are significant. They mean that the walls are working.

But what’s the big deal anyway? Why should anyone care if college campuses bar their neighbors from entering? Isn’t it better to wall off the students and keep adolescent antics from bothering neighborhood residents?

While some imagine benefits, walls correspond to serious setbacks for neighborhood development. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, urbanist Jane Jacobs writes of boundaries in cities as “barriers,” creating “vacuums.” They set in motion “an unbuilding, or running down process.” If people can't walk through an area because of a university wall, they won’t shop at the stores nearby or visit the amenities. Stores close, sidewalks become empty, and safety decreases with fewer eyes on the street. Campus walls aren’t neutral in their neighborhoods. They actively oppose economic development and public safety.

A short walk up Amsterdam Avenue toward Columbia’s campus can show what happens to a university isolated from its neighborhood. Just south of campus, Amsterdam is vibrant, with shops and restaurants and people strolling the sidewalk. Parks and churches dot the avenue. But as you get closer to campus, the stores and restaurants are replaced with imposing walls and the sidewalks become lonely. As you continue past campus, the vitality reemerges. But beware: if you turn down 120th Street, along Columbia’s northern wall, the same loneliness awaits you. The campus barrier smothers development, and if it were removed the neighborhood would have breathing room to improve further.

What’s even more concerning than neighborhood vitality is the educational opportunity these walls prevent. By sending the message that neighborhood residents do not belong on prestigious college campuses, the walls are minimizing the possibility of upward mobility that accompanies such education, continuing the cycle of poverty so often persistent in non-white communities. The United States has always had racial disparities in higher education, with an unfair number of white students able to attend college compared with Black and Hispanic students. While the gap between who starts college is decreasing, there are increasing racial gaps in who achieves a college degree in the U.S.

There are also gaps in the quality of college that people of different races attend. Columbia, Fordham, and St. John’s are among the best-ranked private institutions in New York City. The racial disparities that persist because of their literal and figurative walls are not blocking students from just any college education. Walls prevent under-resourced populations from the education with the most possibility for economic uplift, especially as compared with two-year programs and community colleges.

Even if the walls don’t come down tomorrow, these universities owe it to their neighborhoods to be active and supportive agents to tear down the invisible walls that separate the institutions from their neighborhoods. They should use local vendors for university needs to support the wellbeing of neighbor businesses. They should invite community members to be a part of meetings with politicians or other power players that come to speak on campus.

They should leverage their influence to advocate for the needs of their neighborhoods, and to do so they must really know their neighbors. They need more educational support programs like CSTEP to support non-white and economically disadvantaged students, especially from the nearby community. While these institutions have made strides in this area, more must be done.

Then, it’s time to tear down the physical walls. We ought to be doing everything we can to help students of color envision themselves at our institutions of higher education. Because if they can’t even imagine walking the campus, how could they ever imagine walking the graduation stage?

***

Brian Martindale is a Jesuit seminarian and master’s student in urban studies at Fordham University.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.