The Uniqueness of Dante de Blasio

As New York took in the extent of the win by Bill de Blasio in the Democratic primary for mayor, the impact of a powerful television ad starring his son Dante seemed plain.

The ad hit on de Blasio’s main campaign points of taxing the wealthy, ending a “stop-and-frisk era that unfairly targets people of color” and universal pre-K. But it was the messenger that made it a show-stopper: A mixed-race kid with an exuberant Afro speaking to the camera about how his dad was “the only Democrat with the guts to really break with the Bloomberg years.”

De Blasio’s wife is a black woman, and both Dante and Chiara (his daughter) are mixed race. With his family and the ad featuring his son playing key roles in his campaign, de Blasio split the black vote almost evenly with former comptroller Bill Thompson., the only black candidate for mayor

Remember, in the primary between Hillary Clinton and Obama, who is mixed race, in 2008 Hillary Clinton did better among white and Hispanic voters than she did overall, and Barack Obama won the black vote by a very wide margin in an overall close race. In terms of who voted for whom, race mattered.

{sidebar id=14}

As Joe Lenski, the man behind the exit polls, said in the Daily News, "I don't know if I could ever remember a race where a black guy is (close to) losing the black vote, the woman is losing the woman vote, the Jewish guy is losing the Jewish vote. It's quite impressive .... De Blasio did a good job of saying, 'I'm one of you even though I'm not personally one of you.' He was able to say, 'my wife is African-American, my kids are multiracial."

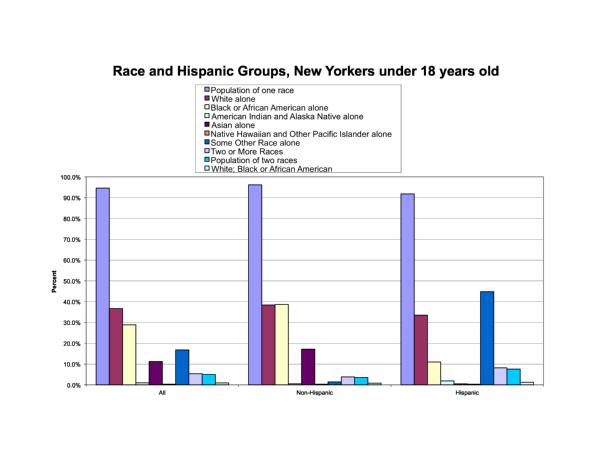

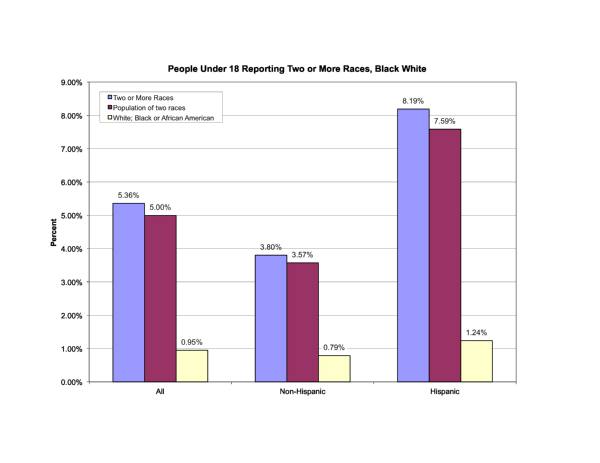

How unique is Dante de Blasio, the 16-year-old superstar of the 2013 elections, who communicated this important message? Just how many New Yorkers are non-Hispanic males who would identify themselves as black and white? An analysis of 2010 Census data shows that very few young New Yorkers are black and white, and even fewer are non-Hispanic black and white. Furthermore, there are much lower proportions of such individuals in New York City in the country at large. These data are presented in the accompanying table, and some are summarized in the two charts below.

For those under 18, there are 94,731 who report being of two or more races; 88,321 of these are of two races, and 16,735 are black and white. When one looks at those reporting that they are non-Hispanic black and white, there are only 8,980. Dante, it is plain, is in a very small group. However, these number also are self-reports; as has become obvious during the last few years, the genetic make-up of individuals does not necessarily mirror their self-reports.

The two charts also make it plain that the city has a lower proportion of multi-racial young people than does the United States in general; this is particularly true with respect to those reporting black and white. In the US as a whole, some 1.67 percent of youth are reported to be black and white, while in New York City the figure is 0.94 percent. (Other comparisons are in the accompanying table.)

But it’s clear that while Dante de Blasio may belong to a small group, the message he delivered was tailored for a much broader audience. It came in the midst of a contentious federal trial over whether the policy was unconstitutionally targeting black and Latinos.

Despite constant refrains by Bloomberg, Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly and some of the media to the contrary, the judge in the stop-and-frisk case, Shira Schiendlin, based her assessment of the practice on expert and factual testimony. Specifically, she drew her opinion on evidence that the police stops young blacks and Latinos disproportionately not only in terms of race and Hispanic status, but also in the neighborhoods that they tend to live in, and in terms of the crime rate in those neighborhoods.

Criminologist Jeffrey Fagan, the plaintiff’s expert in the case, in an article in the Columbia Law Review, has demonstrated that teenagers like Dante — who are perceived as black even though they may be mixed-race — have an 80 percent chance of being stopped. According to father de Blasio, he has discussed this with Dante at length to try to lessen his chances of being stopped.

Plainly, Dante’s uniqueness and the de Blasio family’s uniqueness, along with de Blasio’s position, which plainly attempt to address directly the concerns of many blacks and Latinos in New York City, helps to explain de Blasio’s electoral success.

But while the messenger may have been unique, it was the message that more than likely swayed voters to cast their ballots for his dad. Dante’s uniqueness and the powerful ad just made it possible for the message to get through.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer (www.socialexplorer.com), a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. He is co-editor of “New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future” (Oxford University Press, 2013). The opinions expressed are his alone.

New York’s Changing Electorate: What It Means for the Mayoral Candidates

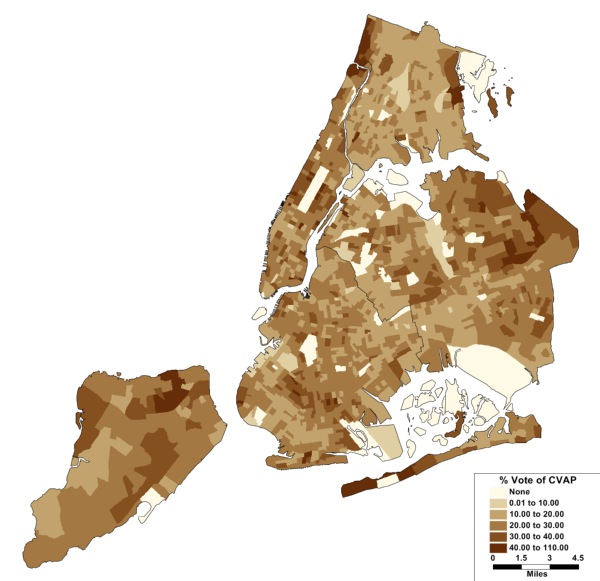

Most New York citizens of voting age do not vote — and they definitely do not vote in mayoral primaries or elections.

That means this year’s candidates, If they have any hope of getting to Gracie Mansion, will need to build coalitions of supporters willing to get to the polls on primary day and Election Day from an increasingly diverse voter roll.

When Barack Obama beat Mitt Romney for President in 2012, less than 50 percent of those in the city who could have qualified to vote did so, with some 2.5 million votes cast. When Michael Bloomberg beat former Comptroller Bill Thompson for mayor in 2009, only 24 percent of those who could have voted did so, with approximately 1.2 million votes cast. The ratios were similar for every election since 1989.

The record in primaries is even worse. In the contested Democratic and Republican primaries for president in 2008, less than 1 million votes were cast or about 20 percent. In the Democratic primary for mayor in 2009, only 330,000 votes were cast — which would mean that only about 11 percent of registered voters — and less of all of those who could enroll and probably would enroll as Democrats bothered to turn out.

New York City has roughly 4.3 million registered active voters and an additional 375,000 inactive voters as of April 2013. So registration of active voters is about 86 percent of citizen of voting age population. However, that number is misleading, since beyond the inactive voters, about 23 percent of NYC registrants are characterized as deadwood for either having moved or died since they registered.

In short, only small fractions of New Yorkers who could vote do vote, and many are not even registered.

Turnout isn’t the only challenge facing candidates; they also must deal with the diversity of the electorate.

Since David Dinkins was elected mayor in 1989, the New York City electorate has also changed substantially both racially and ethnically. Immigrants and their children — many of whom are either Hispanic or non-white — are now eligible to vote, while the proportion of non-Hispanic white voting age citizens in New York City continues to decline.

This shift, however, has yet to propel a non-white candidate to the mayoralty since Dinkins, though it is plain from the candidacies of Fernando Ferrer in 2005 and Thompson in 2009 that Hispanics and blacks will vote for one of their own.

Most notably, the proportion of the electorate that is non-Hispanic white has dropped from 54 percent in 1990 to about 42 percent for the latest year. Most likely it has declined even more since then.

At the same time, the percent of the electorate that is non-Hispanic black has declined to about 24 percent after increasing slightly from 1990 to 2000. Meanwhile, the Hispanic electorate has grown from about 18 to 23 percent, and the Asian electorate has gone from about 4 percent to about 10 percent.

While roughly 90 percent of voting age non-Hispanic white population are citizens, and virtually all Puerto Ricans are citizens, only 26 percent of Mexicans are citizens. For the other Hispanic groups, the range is from the 40 to 60 percent. For instance, about 59 percent of Dominicans over 18 are citizens. (Click to see the tables).

The same pattern holds for the Asian groups. For South Asians, generally about 60 percent of the voting age are citizens, while for the Chinese and Koreans it is also about 60 percent. Both the growth of the immigrant population and the length of time specific groups are in the United States and the extent to which such groups have children and their children become 18 affects the size of the citizen population of each group. So as time goes on, more and more will be citizens and thus have a potential political clout.

The South Asian group is now about 2 percent of the electorate, the Dominicans and Chinese are both about 5 percent, while the Puerto Ricans are 11 percent. All of the other groups are no more than about one percent — and often much smaller. Of course, they are larger in certain areas, but only in a few cases do they approximate an absolute majority.

What then are the general implications of these changes in the electorate and the fact that so few New Yorkers vote in the Mayoral and other local elections?

First, registration of citizens in any group is very important. Due to the limitations of the enrollment data (birthplace is not collected and the count is not an accurate reflection of who is actually in the city and registered to vote), it is very difficult to understand exactly what the registration level is for citizens for each group.

However, getting those who can to file citizenship applications and then get them registered is critical. Once they are enrolled, for a group to maximize its influence it is necessary for them to turnout and vote.

At the same time, because non-Hispanic white electorate has declined to near 40 percent, winning an election means that other groups must work in coalition. If the new groups are split apart or split among themselves and one or more candidates from each group runs a campaign that does not reach across groups, they will undoubtedly lose.

This is a lesson that John Liu learned when he unsuccessfully ran for City Council in 1997. He faced two other opponents of Chinese descent, and challenged an incumbent who famously characterized the increase of Asians in the Flushing area, as an invasion. It was also a hard-earned lesson in the 2001 election when term limits forced a large turnover in the City Council but the number of seats won by community and ethnic activists was very few.

Though the growth of immigrant and ethnic groups can empower such groups, to win elective office usually requires reaching across groups and ethnic divisions and fashioning a winning coalition. It is also means getting members of those groups through the citizenship process, registered and to the polls.

That last step — identifying and getting voters to the polls — is just as important to any candidate as gaining wide public recognition and developing a favorable image. This year’s election may have a high turnout for a primary, but a high turnout would be anything just above 15 percent of those eligible to vote.

Now that New Yorkers are beginning the process of choosing a mayor, looking at the data on the changing electorate simply reinforces the fact about how broad the appeal must be to win elected office in New York City.

Not only do Republican candidates need to go beyond the 16 percent of electorate who enroll in the GOP as Bloomberg and Rudy Giuliani did, but Democratic candidates need to get support beyond their ethnic group and local area to even have chance.

Given all of this, it is not surprising that few are certain where the current election will go, either during the primary in September, the likely Democratic runoff, or the final election in November.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer (www.socialexplorer.com), a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. He is co-editor of “New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future” (Oxford University Press, 2013). The opinions expressed are his alone.

What The Next City Council Will Likely Look Like

The next City Council will likely be demographically similar to the current one, though there may be an increase in both Asian and Latino membership.

That is one of the main takeaways from a review of the new Council lines approved by the city’s Districting Commission on Thursday but not released to the public until the following day.

A further look at the plan shows that it continues to protect incumbents, but was adjusted to accommodate some of the preferences of community and minority group advocates and others who complained loudly about the preliminary plan.

In addition, Lisa Hadley, a noted analyst of voting patterns in the context of redistricting, assessed the plan for any vulnerability to challenge by the Department of Justice and by Minority Voting Rights advocates and found that it unlikely to raise any issues.

Incumbency Protection

On average the new districts retain slightly over 87 percent of the population of the current districts, and 41 districts have at least 80 percent of that population.

Overall the plan continues the time honored tradition of incumbency protection, but it is worth noting that such concern for incumbents has been found by the Supreme Court to be a legitimate basis for redistricting.

However, there were noteworthy changes to districting lines that addressed concerns of critics.

A look at the data shows that a set of districts in northern Manhattan and the Bronx had large changes from 2003 to the new lines: Districts 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, and 15. It is also plain that 7, 8, 10, 14, 15, and 17, were changed substantially between the preliminary and the final plan.

This accommodates Hispanic and African American population change.

There was also substantial change between the current lines and the final lines, in Queens for Districts 25, 29, 32, and for District 39 in Brooklyn. Districts 25, 29 and 32 were modified substantially from the preliminary plan. Along with District 28, these changes satisfied some of the issues raised by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Nonetheless, the basic pattern except for the 10 districts noted, was for a plan that would serve to protect the incumbents or their likely successors.

Voting Rights Issues

Like many southern states and counties, the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn are subject to so-called pre-clearance by the Department of Justice.

This is to ensure that any changes to the voting system do not disadvantage minority groups: African Americans, Hispanics and Asians.

Generally a plan is tested to see if there is retrogression, which means that one would expect that fewer seats would be held by candidates of choice of minority groups.

The commission hired Lisa Hadley to conduct an analysis to assess whether the final plan met such a criterion. (I should note that in several cases, including a recent case in Port Chester, Lisa Hadley and I testified for the same parties. My work was more in formulating and analyzing the demographics of redistricting plans, while Lisa Hadley analyzed voting patterns.)

Hadley’s analysis finds that the plan passed by the redistricting commission preserves at least the same number of seats, where minorities will elect their candidate of choice compared to the current plan in the three covered counties.

I agree with Hadley on this, the plan will return a Council very similar demographically to the current council, though their may be an increase in both Asian and Latino membership.

A Jigsaw Puzzle

Redistricting for any jurisdiction is a series of tradeoffs among incumbency protection while following the five principles I outlined in an earlier column.

How these principles, along with incumbency protection, are implemented in practice depends on who is doing the map drawing. Redistricting is a bit like completing a jigsaw puzzle. All territory must go somewhere.

New York City redistricting is done by a Commission where a majority of members are appointed by the Council, while many of the mayoral appointees also have been very active politically. Though not exactly the same as being drawn by the Council itself, the Council still must approve the plan, and those in charge of drawing the map are beholden to the Council for their appointments.

If we had true non-partisan (as opposed to bi-partisan) redistricting in New York City, I am sure that incumbency would not play such a large role. (Indeed, it played little or no role in California, where the state’s recent redistricting was done by an independent non-partisan commission.)

Unless New York City adopts such a procedure, we can expect that the choice of constituents will still be shaped by the incumbents more than by the voters.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.