Good News About Asthma

A mural in Greenpoint, Brooklyn

If you are like me, you missed an amazing bit of data buried in a New York Times article about the widening gap between the city’s rich and poor on a range of chronic illness.

A couple of weeks ago, the Times reported that asthma hospitalization rates “plummeted” in the last decade. That news would have been easy to miss. The article was headlined, "Gap in Illness Rates Between Rich and Poor New Yorkers Is Widening, Study Shows" and reported on a study by the New York City comptroller, William Thompson, Jr., which showed that children went to the hospital for asthma emergencies far less frequently in 2005 than in 1995.

(Special thanks here go to Carbon Tax Center co-founder and master number cruncher Charlie Komanoff for bringing the story to my attention, with kudos to community activist Ed Ravin and some of my Natural Resources Defense Council colleagues for many helpful insights that also inform this article.)

Here are the key data points: Children in the poorest sixth of the city, in terms of neighborhood median household income, saw their asthma hospitalization rate plummet by 47.4 percent. In the next half of neighborhoods, the rate dropped by 55.3 percent.

To put it another way: In the poorest third of the city, half as many kids went to the hospital because of an asthma attack in 2005 than in 1995.

This is amazing news. As somebody who has spent most of the past 15 years working to reduce diesel pollution, I’m stunned. And, as somebody who watches how the media covers health and the environment very closely, I’m equally stunned at the lack of media coverage about this kernel of the story. (Let’s face it: A gap in diabetes rates between East 63rd Street and East 103rd Street is no longer, regrettably, “Man bites dog.” But cutting the number of kids going to the emergency room for asthma — in the city’s poorest neighborhoods — surely is.)

Behind the Story

How has this drop in child asthma hospitalization rates happened?

Of course, parents, children, doctors and nurses deserve the lion’s share of credit for their response, across the board, to the asthma epidemic that hit New York City and other cities in the past two decades. Kids got sick, parents got involved, and doctors and nurses figured out better ways to treat asthmatic children.

But smarter policy choices are contributing too, by reducing the known triggers of asthma emergencies. We don’t know what “causes” asthma, but we do know that many commonly found substances can trigger an asthma episode. For example, we know that ultra fine particles in diesel exhaust can trigger an asthma attack.

Cleaner Buses, Cleaner Air

Over the past decade, New York City Transit invested hundreds of millions of dollars in new, cleaner diesel, natural gas and hybrid-electric buses that are equipped with the most advanced, state-of-the-art pollution controls. The transportation authority sped up the retirement of hundreds of old, two-stroke diesel buses that lacked any meaningful pollution controls, putting them out of service in some cases, up to six years ahead of the normal schedule. As a result, the fleet’s buses are 97 percent cleaner than they were in 1995.

So, while our region still fails to meet federal Environmental Protection Agency health standards for ground-level ozone and particulate soot pollution, diesel soot levels have been dramatically reduced where it counts most — on the sidewalks of many New York City neighborhoods, including the low-income areas and communities of color that have housed NYC Transit bus depots for decades.

The Great Unknowns

Asthma hospitalization rates, though, are clearly dropping faster than our pollution levels.

Why?

I don’t know. But a few questions, if answered, may help us understand what’s going on.

First, what has been the role of community-based health facilities and mobile medical units, both of which are far more prevalent than they were a decade ago? Are there fewer asthmatic kids—or are they just being treated close to home and not in hospital emergency rooms?

First, what has been the role of community-based health facilities and mobile medical units, both of which are far more prevalent than they were a decade ago? Are there fewer asthmatic kids—or are they just being treated close to home and not in hospital emergency rooms?

Second, what has changed in the drugs being prescribed and in the frequency of those prescriptions? Are children taking more effective drugs for asthma conditions? If so, that would suggest asthma rates remain the same but that asthma treatment is working. If fewer children are taking drugs, that could mean that asthma itself has actually dropped.

Third, has anything changed in the diagnoses being handed out? A personal example: A couple of years ago, my infant son had a breathing emergency that led him to the hospital. During the epic that followed, I asked several of the healthcare professionals I met whether he had asthma. Across the board, their response could be paraphrased as, “it depends how you define asthma.” In other words, some doctors would have looked at my son and checked the box marked “asthma.” Others would have diagnosed an allergic reaction and taken a more wait-and-see approach.

Fourth, has there been a similar drop in asthma-related school absences? According to the city health department, asthma is a leading cause of school absences. So, if child asthma hospitalization rates have been cut in half in many neighborhoods, school attendance should have increased somewhat to account for all of the now-healthy children.

The Fruits of Knowledge

Clearly, there is a level of awareness of, and service for, asthma that did not exist in 1995. In my son’s case, he was ultimately diagnosed with, and treated for, a soy allergy, and we put the inhaler away for good. Throughout the system, children, parents, teachers, nurses, doctors and other healthcare providers all are doing a better job at diagnosing, treating and managing the asthma (and non-asthmatic allergies) of our city’s children.

Since 1999, the health department’s Asthma Initiative has coordinated the NYC Asthma Partnership, a citywide coalition of more than 300 organizations and individuals. It manages an impressive array of educational and training programs for schools, daycare facilities, healthcare institutions and other key links in the asthma services chain. (Check out their Web site, which includes neighborhood-by-neighborhood data, summaries of available education and training programs and much more).

But I’m still wondering about the four questions posed above. Mostly, I’m trying to figure out whether asthma itself has been reduced, or whether it’s being moved out of the city’s emergency rooms. If you have thoughts on this, post a comment. Maybe we can all get to the bottom of this story.

( I am so stunned by the data—and the lack of coverage—that I decided to write about this asthma story, rather than the article about PlaNYC that I promised you last month. Look for that story in November.)

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization, and is on the boards of the New York League of Conservation Voters and Transportation Alternatives. In addition to his Gotham Gazette pieces, he blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard at http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/rkassel.

Â

Grading the City's Public Hospitals

New York City is a world of infinite decisions: Japanese or Vietnamese, a ball game or the opera and the subway or a cab.

Some decisions, though, involve more serious matters. Selecting a hospital is one. But now New Yorkers trying to decide whether to go to Coney Island Hospital or Kings County Hospital Center have a little more information to guide them.

Last month on its Web site, the city’s Health and Hospitals Corporation voluntarily released infection and mortality rates for each of its 11 public hospitals. It was the first hospital system in the state to do so, said the corporation's chief executive officer and president, Alan D. Aviles.

The data, which is accessible here, compares the corporation's facilities with regional and national averages and allows New Yorkers to analyze and compare hospital against hospital.

Hailed by health care advocates for casting light on a secretive industry, the release of this data has shifted attention to the perception of public hospitals and their ability to provide quality care in all five boroughs. Although the corporation's acute care facilities score above state and national averages, a familiar discrepancy emerges within its own network: Hospitals in lower income areas tend to do worse than those in higher income areas.

The Information Trend

Although most of the information the corporation has posted on its Web site is regurgitated from either the state or federal hospital reporting system (which are also available online here federally and here on the state level), the corporation added specific mortality data on each hospital and statistics on infections acquired in hospitals. Since the corporation took this step last month, another New York hospital–North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System – has already followed its lead.

New York State began releasing hospital mortality data on coronary bypass surgery in the late 1980s. Then, the public information movement stalled. Advocates attributed this to an increasingly powerful health care industry and a reluctance to disseminate seemingly private information.

" If we back up 20 to 30 years, health care was a very private transaction between a patient and a physician," said former state legislator James R. Tallon, now the president of United Hospital Fund of New York, a health care policy organization. "In a sense it's sort of a movement to say we are going to make it more publicly available. We live in a world where information moves much more freely."

In 2005, the state legislature approved more rigorous reporting standards, which would result in the release of hospital report cards and hospital-related infection rates in 2009. Those regulations are currently being rolled out.

The Health and Hospitals Corporation's voluntary release of its data puts it a step ahead of the state statute.

The Corporation's Score

Overall, the corporation's hospitals have average mortality rates that are better than state, regional and federal averages.

However, its average mortality rate following heart attacks is slightly worse than the statewide figure – the corporation had 15.8 patients die within 30 days of a heart attack from July 2005 to June 2006, while the statewide average is 15.6. For heart failure, based on the same 30-day measure in the same time period, the corporation scored better than the statewide average -- 10.6 compared to 11.

Data on the death rates from heart failure and heart attacks were provided by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which take into account only Medicare patients. Those patients, said Aviles, comprise just 15 percent of the corporation’s patient base.

When comparing the corporation's 11 hospitals, a familiar outcome is apparent: Facilities in the outer boroughs and in more impoverished neighborhoods have higher mortality rates than those in Manhattan.

" Quite frankly, we're talking about the hospitals in the outer boroughs and the health of the communities is often poorer," said Aviles. "There are more patients with low incomes, that are uninsured," he added.

For hospital wide mortality rates, the lowest ranking facilities – Coney Island Hospital in Brooklyn at 3.14 percent, Kings County Hospital Center in Brooklyn at 1.72 percent and Elmhurst Hospital Center in Queens at 1.64 percent – are all located in the outer boroughs.

The hospital wide mortality rates are not risk adjusted, Aviles said, and so do not take into account the types of patients or trauma seen at each location. Because the Coney Island center sees a disproportionate number of elderly nursing home patients and Elmhurst sees terminally ill patients needing hospice care, the figures might not accurately reflect the facility's quality. The hospitals with the lowest mortality rates, including North Central Bronx Hospital at .67 percent, followed by Manhattan-based Metropolitan Hospital Center at .68 and Queens Hospital Center at .96 percent, were not all in Manhattan either.

The corporation's acute care facilities are dispersed throughout the boroughs: Brooklyn has four hospitals, Manhattan has three and both the Bronx and Queens have two (Staten Island has one rehabilitation facility).

None of the three Manhattan facilities ever fell within the bottom quarter of the corporation's mortality lists, and one, Metropolitan Hospital Center, was always among the three hospitals with the lowest mortality rates based on hospital wide, heart failure and heart attack data. On the other hand, Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx has one of the highest mortality rates for both heart attacks and heart failure.

Data on hospital-related infections had similar results. Patients in hospitals in the outer boroughs accumulated infections more frequently than those in Manhattan.

When comparing preventable, sometimes-fatal bloodstream infections affecting patients in intensive care units – otherwise known as central line infections – Kings County again sank to the bottom of the corporation's list with 11 per 1,000 CL days, which takes into account the number of days and amount of patients with a central line. A Manhattan hospital, Bellevue Hospital Center, topped the list with a rate of 1.7. Numerous hospitals in the outer boroughs went more than four months without having a central line infection.

The Health Care Gap

Because patients outside of Manhattan are more likely to be uninsured, said Aviles, they do not have the same access to preventative medicine. They may not have a primary physician or are recent immigrants. Also, the corporation's president added, many of the hospitals in the outer boroughs, like Jacobi Medical Center, Kings County and Elmhurst, serve as trauma centers – locations that would obviously see an influx of patients who are injured more severely.

The discrepancies in access to health care based on race and income have been documented previously. A report released last month by City Comptroller William Thompson showed residents of lower income neighborhoods are more likely to suffer from heart disease, diabetes and cancer than people in more affluent areas.

Although quality of care disparities by borough are evident in the corporation's data, many advocates said the public hospitals in poorer neighborhoods have come a long way since the 1990s.

Public Versus Private Care

The Giuliani administration’s lack of support for the city's public hospitals left the facilities without sufficient resources to provide proper care, said some advocates. And with that, they added, came the public perception that public hospitals were less reliable and safe than private ones.

The Health and Hospitals Corporation, however, has received renewed attention during Mayor Michael Bloomberg's tenure. With a $200 million boost to its operating budget in 2004, Bloomberg aimed at reinvigorating the public health industry. That effort has been seen in the hospital's greater ability to provide quality health care, said Aviles.

" We have a mayor that is very knowledgeable about health care," the corporation's president said. "We're just glad that we're getting to the point that we have data (that reflects) what the mayor is saying."

Even Aviles recognizes that many New Yorkers see public hospitals as riskier than private ones. That stereotype, he added, is outdated, thanks to Bloomberg.

The data helps point to the better quality of care at the corporation's facilities. Many of the intensive care units within the corporation have reduced central line bloodstream infections by 30 percent over the last two years, according to the corporation.

" There has sort of been over the years a public perception that public hospitals are not as good as private hospitals," said Arthur A. Levin, the director of the New York City based Center for Medical Consumers. "I'm sure that is the reason why HHC published this data. It makes them look really good."

The Data Debate

Because a large chunk of the data released by the corporation only measures Medicare patients and the overall mortality rates do not take into account a patient’s age or ailment, some advocates argue the data does not accurately measure quality of care.

Bruce Boissonnault, president and chief executive officer of Niagara Health Quality Coalition, which independently measures all the state's hospitals, said the corporation's move to release data is commendable, but medical consumers in New York State must keep in mind the source of information. Measuring whether a patient receives an aspirin when having a heart attack, does not necessarily mean that patient survives, he added. Context is everything.

"What you want to know is which hospital do I need to go to to walk out of the hospital alive, and where do I go to get a doctor that will follow up," said Boissonnault.

Boisssonault's group examines millions of anonymous patient records to score hospitals statewide. According to its measurements, most of the corporation's hospitals fall within the state average for mortality indicators based on inpatient conditions.

Since the state, let alone the country, are relatively new at collecting quality of care data, advocates said, no research methodology or data collection system is going to perfectly reflect a hospital's quality. "Because we're in the infancy of collecting data on (quality of care) measurements and reporting it, there are problems," said Levin. But, he added, "Do you wait for the perfect, or do you wait for the good enough?"Â

Aging with AIDS

When Edward Shaw was diagnosed with the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, in August 1988, he thought it was a death sentence. But now, the burly, 66-year-old resident of the Upper West Side seems far removed from the nearly two-decade old diagnosis.

"I smile a lot," Shaw said with a chuckle on a recent afternoon.

Shaw is not alone. As antiretroviral drugs become increasingly successful at keeping people with HIV alive and healthy, the virus is steadily trickling into a once-unforeseen population - seniors.

HIV victim turned AIDS activist, Shaw, in partnership with several New York City-based nonprofit and advocacy organizations, has helped spearhead a city-funded campaign to educate this growing population on the dangers and prevalence of HIV and AIDS. That campaign is intended to put HIV prevention information in the hallways of senior centers and condoms in the pockets of elderly New Yorkers.

Treating a New Population

When HIV was first diagnosed in 1981 it was a disease that supposedly infected only gay men. In fact, AIDS went by another acronym - GRID or gay-related immune deficiency.

As information spread, so did the disease. From intravenous drugs users to heterosexual women and men of all races, it is now readily acknowledged that HIV and AIDS do not discriminate.

But a HIV diagnosis is also no longer judgment day for many individuals. Drug cocktails introduced in the mid to late 1990s - which may require a daily regimen of a dozen pills - have kept those diagnosed with HIV in the 1980s healthy for decades. And while people with the virus continue to grow older and remain sexually active, they may expose other older New Yorkers to the virus, said AIDS advocates.

According to the city's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, nearly 100,000 individuals are living with HIV or AIDS in New York City. As of July 2006, more than 31 percent of them were over the age of 50 and 70 percent were over the age of 40.

New York City has long been a hub for populations infected with HIV – the city has the highest rate in the country – and the aging population here might foreshadow a national trend.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, those over 50 account for 12.5 percent of the approximately million individuals living with AIDS in the United States. That same age bracket comprised an estimated 15 percent of the new cases of HIV from 33 states in 2005.

From 1991 to 1996, new AIDS cases in the over 50-population increased by 22 percent nationally, according to a report by the City Council's committees on health, aging and senior centers. During that same time period, new cases for those between 13 and 49 years old increased by 9 percent.

A report released by the New York City-based AIDS Community Research Initiative of America, said it is "probable" that the majority of people living with AIDS could reach 50 years old within the next decade. That could complicate HIV education, access to healthcare and how health care providers and city officials address, prevent and mange the virus.

Safe Sex for Seniors

Shaw was 47 years old when he learned he had contracted HIV. Because he is not gay and information on contracting HIV from intravenous drug use – which was how Shaw was infected – was not widespread, he figured this growing pandemic couldn't affect him.

"I had to reeducate myself about this thing that was ravaging my body," Shaw said of his diagnosis's aftermath. "Back in 1988, there was little if any information in the community, specifically to reach older adults. The little knowledge I had then was it affected gay white men, it affected homosexuals, and it affected folks from Africa. My not being any of those, I said, 'Well, I don't have anything to worry about.' Or so I thought."

That same indifference is seen now in senior populations. Older people do not realize they too can contract HIV, Shaw said.

Although seniors remain sexually active as they age, menopause and a lack of education make using condoms a rarity, advocates said. Even talking about sex is often taboo in senior centers and specialized geriatric medical offices.

"You have to get seniors to start comfortably talking about sex," said Bobbie Sackman, director of public policy at the Council of Senior Centers and Services. "This population has never been targeted for education. … Seniors have sex."

HIV status, one survey found, does not deter seniors from sexual activity. A survey of 914 New York City residents with HIV or AIDS over the age of 50 conducted by the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America found that half were sexually active and, of them, more than 30 percent had sex with individuals regardless of their HIV status.

Treating and Diagnosing the Elderly with HIV

While treating AIDS at any age is difficult, it can be more difficult for those growing old with HIV or contracting it in later years. Dr. Monica Sweeney, assistant commissioner of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said that, as the body grows older, the kidneys become less likely to handle medication. Other HIV prescriptions can increase the risk of heart disease – a dangerous side effect for those over 50.

"Just becoming a senior makes all of your treatments more difficult because of the natural and biological effects of aging," said Sweeney.

According to ACRIA's report, little research has been conducted on the effects of HIV on other ailments, like cardiovascular disease or osteoporosis, typically associated with seniors. But what several studies have shown, according to the report, is that seniors have a vastly higher chance of living with HIV if they are treated with antiretroviral drugs. If untreated, older individuals are twice as likely to die from the virus than younger populations.

Many of the symptoms associated with HIV or AIDS are also associated with aging – such as weight loss, memory loss, fatigue and shortness of breath. As a result, some seniors wither away from AIDS undiagnosed, assuming their health problems are from aging. But in the meantime, they may still be having unprotected sex.

"You can see the way the virus is ravaging the bodies of the elderly, yet they are walking around with it not knowing," said Shaw. "And not realizing that that ache or that loss of appetite or that dementia is an AIDS symptom, not an aging symptom."

Elderly individuals diagnosed with HIV are also at risk of more than the usual physical ailments. Daniel Tietz, executive director of the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America, said seniors who have HIV or AIDS are twice as likely to live alone as other New Yorkers in the same age bracket. The loneliness that may accompany that statistic could increase the risk of suffering from the mental side effects of the virus.

Treating seniors like the rest of the "at risk" population is part of addressing the problem. Overall, Sweeney said, it is misguided to single out any constituency, color or ethnicity - everyone needs to get tested.

What the City is Doing

Following a joint hearing by the aging and health committees and the senior centers subcommittee of the City Council last year, Councilmember Maria del Carmen Arroyo and AIDS advocates established a working group to come up with a program aimed at seniors.

"Aging in it of itself is a challenge," said Arroyo. "Complicate that with HIV and AIDS and the health care provider and community organizations have a greater challenge to meet the needs."

With a $1 million budget appropriation, several New York City groups are drafting a training curriculum for senior service providers, including senior center employees and medical professionals, that will direct them on how to educate seniors about safe sex, AIDS and HIV. The funding will also go toward educational materials for seniors and intensified programs in the council districts where HIV and AIDS are most prevalent and seniors are most at risk.

The program is the first in the country, advocates said, and the first in the city to target seniors exclusively for HIV and AIDS education. Although the health department, officials said, has distributed literature and conducted prevention programs citywide, this program would address the hesitations and apprehension of the elderly to talk about sex - let alone safe sex.

By next year, advocates said, every council district would have held at least a training session for senior service providers.

In addition to the City Council initiative, the city's Department of Aging has also recently offered free HIV tests and distributed condoms at senior centers.

Getting Gray and Being OK

As medical breakthroughs occur and those with HIV continue to live longer, Shaw and advocates agree education and prevention will become increasingly important.

While he hopes for a vaccine in his lifetime, until then Shaw will continue to visit senior centers and churches to shed light on HIV and AIDS for seniors. With two decades down since his diagnosis, he has a lifetime of advocacy and education to go.

"Education, education, education," he said. "And as often as possible."

Â

Guaranteeing Access to Abortion in New York

In New York State until 1970, abortion was considered homicide unless the procedure was to save the life of a pregnant woman. Then three years before the Supreme Court decision in Roe v Wade made abortion legal in the United States, New York State partially decriminalized abortion. But abortion was still classified as murder if it caused "the death of a person or an unborn child with which a female has been pregnant for more than 24 weeks." That law remains on the books until this day.

Now, however, with little fanfare, a bill has been introduced to once again revise New York’s laws, which some have called "antiquated and unconstitutional." This act would bring New York’s laws on abortion up to date and recognize a woman’s fundamental right to make medical decisions relating to reproduction. For the first time, "person, when referring to the victim of homicide [would mean] a human being who has been born and is alive."

BEFORE 1970

Prior to the 1970 revision, women with unwanted pregnancies either had unwanted children or found some way to terminate their pregnancies. Often these illegal operations were expensive and performed blindfolded, in a back alley, or under unsanitary conditions by “quacks,” sometimes working without anesthetics or antibiotics, who could permanently harm or even kill their patients.

These came to be known as coat hanger abortions for the “medical" instrument used in performing them. The coat hanger or other device, used by a pregnant woman or someone assisting her, could perforate the woman’s uterus, sometimes causing severe bleeding. Ironically, such injuries were sometimes the only thing that allowed her to get medical attention.

Women who could afford to check into mental hospitals and have two psychiatrists certify that they might commit suicide if they had to continue a pregnancy could get a legal abortion by claiming the procedure was literally a case of life or death. Others who had money could go to foreign countries for the procedure. And some women did have access to licensed, cooperative physicians.

Even for those women able to get safe abortions, though, the criminal law controlled the process. Abortion was murder except where medical testimony established that the pregnant woman’s life was at risk. There was no right to choose, though the euphemism "right to choose," had not yet come into use, nor had the euphemism, "pro-life," meaning, respectively, for or against a woman’s choice to be or not be a mother at a given time.

In the late 1960s activists in the women’s liberation movement argued that women should have control of their bodies. In response, the state legislature amended the penal law. Under the changes, doctors performing abortions in the first 24 weeks of pregnancy would no longer risk being criminally prosecuted and losing their licenses, and women would no longer risk losing their lives.

Revolutionary though it was at the time, the 1970 law, which partially decriminalized abortion and took it out of the realm of homicide in most cases, did not go beyond that. Today, abortion in New York State remains defined as homicide when performed after 24 weeks unless the woman’s life is at risk. But now more than three and one-half decades later, when observers and activists say changes in the Supreme Court could again threaten women’s choice, New York is putting this health issue on the legislative agenda.

WHAT THE CHANGE WOULD DO

The Reproductive Health and Privacy Protection Act, proposed by Governor Eliot Spitzer, would establish and recognize reproductive rights and privacy. The bill would guarantee the right to abortion; it would also guarantee rights with respect to contraception including, for example, the purchase of birth control or "morning after" pills. It would amend the public health law, the education law, the penal law and criminal procedure law, and certain other statutes, all in relation to abortion. Specifically the bill contains a statement of a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy before the fetus is medically determined to be viable or at any time necessary to preserve the woman’s life or health. According to lawyers who have assisted the Spitzer’s office in drafting the legislation, perhaps most significantly, it would recognize that the issue of abortion is medical, rather than legal or political.

Currently, New York does not have any provision for abortion after viability to protect a woman’s health. Also, the procedure remains criminal after 24 weeks even if the fetus is not viable -- "even if the fetus is dead," according to Dr. Maureen Paul, chief medical officer of Planned Parenthood of New York City. The law bans all abortion after 24 weeks except when necessary to preserve a woman’s life, although Paul says, "A threat to health is a threat to life."

Under the proposed changes, these statutes would be repealed and the bill would allow a woman to end a pregnancy until viability or at any time necessary to protect her life or health.

ADDRESSING FEDERAL CHANGES

New York’s existing law was never challenged, but until this year federal court decisions had determined that laws restricting abortion after 24 weeks are unenforceable when the procedure is needed to protect a woman’s health. Then earlier this year in their second Gonzales v Carhart ruling on late-term abortions, the Supreme Court decided that the "state’s interest in promoting respect for human life in all stages of pregnancy could outweigh a woman’s interest in protecting her own health." That decision means that New York laws would no longer be adequate to insure that women who needed them would be able to obtain abortions in later stages of pregnancy.

By addressing that issue directly, advocates say, New York would make a major commitment to protecting the rights intended by a majority of the sitting justices’ predecessors three and a half decades ago. If the current state bill is enacted into law, it will reflect the public policy of New York by declaring that every individual has a fundamental right of privacy with respect to personal reproductive decisions and the right to refuse or choose contraception. It would make clear that in New York State every female can determine the right to bear a child and terminate a pregnancy prior to viability, or whenever it is necessary to protect her life or health.

In the wake of recent court rulings, and anticipating decisions in the future, abortion rights advocates are increasingly turning their attention to the state level. In this state, the proposed legislation "will ensure that New York remains a beacon for choice in the face of broad federal attacks on reproductive health and women’s rights," said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, which participated in the drafting of the bill. "The Reproductive Health and Privacy Protection Act would be just that. It would make reproductive rights a matter of health, not law and politics," she said.

Unless the state legislature returns for a special session later this year, the bill is unlikely to win passage in 2007. But supporters say they will press for the legislation. NARAL Pro-Choice New York, for example, has said it will target key state senators who have opposed the bill “until the bill is passed.

For their part, antiabortion advocates are working to defeat the measure. In a “memorandum of opposition,” the New York State Catholic Conference listed objections to specific provisions of the bill, including its guarantee of privacy rights and its removal of New York abortion laws from the criminal code. Calling the bill “uncompromising in its terms and extremely sweeping in scope,” the statement said the measure “goes against the increasingly pro-life sentiment in this country,”

Let the wars begin.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court JusticeÂ

Access to the HPV Vaccine in NYC

Young mothers whisk by pushing baby strollers heading toward the pediatric floor at the Gouverneur healthcare facility on the outskirts of Manhattan's Chinatown.

Even on a slower than usual Monday, mothers and children clutter the waiting area, where signs promote a brand new vaccine and urge parents to ponder "how (their) daughter could become one less affected."

At Gouverneur and other medical care facilities within the city's Health and Hospitals Corporation, check-ups for girls as young as 11 years old can now include a vaccine aimed at wiping out four types of a virus that causes 70 percent of all cervical cancers - the Human Papillomavirus or HPV.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved only one vaccine for the virus – Merck's Gardasil. Both the Health and Hospitals Corporation as well and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene say they are pushing immunization for girls between the ages of 11 and 18 and are making it more accessible, both physically and financially, across the five boroughs. But others say the city is not doing enough.

A Campaign Against Cancer

Approximately 11,000 new cases of cervical cancer are reported every year of which 3,000 are fatal, according to the American Cancer Society. The vast majority are caused by HPV - the most common sexually transmitted disease in the country that is known to cause genital warts. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration last summer, Gardasil, administered over six months in three doses, protects against four types of HPV.

Gardasil is increasingly in demand in the city - thanks to a tailored media campaign by Merck, medical professionals said. But although the vaccine has been applauded by medical professional far and wide, access has been an issue due to its exorbitant cost – estimated at nearly $400 for the entire immunization.

The cost can deter women of lower incomes from perusing the vaccination. This poses a particular problem in New York City, where minority women are screened far less for cervical cancer than other women. By skipping an annual Pap test – an exam that screens for cervical cancer – women are less likely to catch the disease early on before it is to late. In 2004, according to a survey by the health department, 41 percent of Asian women said they had not had a Pap screening in the last three years.

The national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended the vaccine be given to girls age 11 and 12 and that older females, from ages 13 to 26, be given a "catch up" vaccination. The vaccine is licensed for women ages 9 through 26 and is aimed at younger populations to catch them before they become sexually active.

It is estimated that 80 percent of women will be exposed to the virus by age 50, and 6.2 million new infections occur annually throughout the country.

Access in NYC

A report released in March by Gotbaum found that just over half of the child and teen clinics within the Health and Hospitals Corporation offered the vaccine. The corporation contends this figure is flawed and inaccurate (it blamed uneducated phone operators). In a statement, the corporation said it had always provided the vaccine at its facilities.

Gotbaum’s report also took issue with the health department, which it found did not offer the vaccine at any of its sexually transmitted disease walk-in clinics or its immunization clinics. Most of these facilities cater to uninsured, low-income or minority populations that otherwise would not be able to afford the vaccine.

Public Health Post-Study

The hospitals corporation now provides the vaccine at its 11 hospitals and its community based healthcare centers. For families that meet income qualifications, which apply to individuals with an income below 400 percent of the federal poverty level, the cost of the vaccine is integrated into the cost of a visit. This means uninsured patients who qualify for the corporation's financial assistance program would not have to pay an extra fee to receive the vaccine. A visit can typically cost between $15 and $60, depending on income and family size.

The health department is now offering the vaccine at its four, year-round immunization clinics. The health department's assistant commissioner who heads the bureau of immunization, Dr. Jane Zucker, said that since the department started offering the vaccine in May, it has administered 150 shots at its immunization clinics.

Since this spring, through the federal Vaccines for Children program, the department has also distributed 75,000 free doses for eligible children 18 years old and under to an array of health care providers throughout the city. The department, Zucker said, is also pushing to make the vaccine available for children through their primary care physicians.

"The most important thing is to make sure that kids have access through their doctor's office," said Zucker. "The most important thing is to make sure that all providers… that all venues have access to the vaccine."

The department is not offering the vaccine at its sexually transmitted disease walk-in clinics, because the clinics are not meant to provide routine medical care, officials said. Based on its experience with the Hepatitis B vaccine, health officials said it is unlikely a patient would return to the clinic for all three doses. Without all of the doses, the effectiveness of the vaccine is questionable.

Gotbaum’s report recommended the inclusion of the HPV vaccine in immunization services provided at the sexually transmitted disease walk-in clinics. Another recommendation – providing information about the vaccine on the city's non-emergency hotline 311 – has been implemented, health officials said.

Reaching Women Over 18

Some community-based clinics are struggling with whether, or even how, to provide the vaccine to women over 18 who are uninsured, sexually active and are not eligible for the free vaccines under the Vaccines for Children program. Although the vaccine is recommended for young women who are not yet sexually active, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did not disregard its positive effects on women up to 26 years old.

Elizabeth Howell of the nonprofit healthcare provider, Community Healthcare Network, said it currently provides the vaccine only to those less than 18 years old. Howell said there is no system to get their patients – who are low income and uninsured - to come back for multiple doses.

"We’re in a catch 22," she said. "We can't offer it freely. We don’t have the resources to offer it to anyone off the street."

Planned Parenthood does not provide the vaccine. Neither does the Medical and Health Research Association of New York City, which is dedicated to researching and providing health care to underserved populations.

A Popular Shot

Unlike community or nonprofit clinics, physicians and nurses in the Department of Pediatrics at Gouverneur see Gardasil increasingly becoming a routine step in preventative medicine. They have worked with private providers of Gardasil to vaccinate women above 18 years old, regardless of sexual history.

"Professional medicine is the key to this whole HPV (prevalence)," said assistant director of pediatrics Lily Yiu. Yiu's own 18-year-old daughter will soon be taking her third and final dose of the vaccine.

The director of the pediatric department, Dr. Felix Santiago, said the vaccine has been integrated into the medical center's immunization processes and has been classified as a "recommended" vaccination. (Medical professionals interviewed at Gouverneur would not explicitly back Gardasil as a mandate).

Health professionals who interact with young girls everyday are seeing the popularity of the vaccination first hand. Gloria Perez, a pediatric nurse practitioner at Gouverneur, said most of her patients come in knowing about Gardasil, and some college-aged girls make specific visits in just for it.

"It's in their teen magazines. It's in the subways," Perez said of Merck's advertisements. "It's part of your wealth visits. It's part of your health maintenance visits, just like any of the other shots are."

Since it was introduced in the center in December, nearly 100 percent of patients have opted for the vaccine when offered, the director added.

The Public Perspective

Gardasil has taken the nation by storm and sparked heated debates in legislatures across the country. But with any political storm, usually comes a thunderous backlash.

In Texas, the legislature rescinded an executive order by Governor Rick Perry that mandated the vaccine for all young girls. Some parents and advocates have claimed a requirement would encourage young girls to have sex, while others objected for religious reasons.

Since then, 25 states, including New York, have considered mandating the vaccine. Assemblywoman Amy Paulin of Scarsdale introduced a bill this past legislative session that would have required the vaccine for school-aged girls, although it would have allowed parents to opt out for religious reasons. The measure was unsuccessful and never received a co-sponsor in the Senate, but Paulin intends on introducing it again in hopes of improving access to the vaccine for all socioeconomic classes.

"With a vaccine like this, one that requires three dosages, you often see families go for the first one, maybe even the second one and forget the third one," said Paulin. "(A mandate) also closes the socioeconomic gap. Poor children do not get vaccines unless they are mandated."

Although the City Council has held hearings on the subject, Councilmember Helen Sears, chair of the Women's Issues Committee, said the council is currently taking a wait and see position on the vaccine. Sears said she hopes to work with the health department and monitor the vaccine's success and popularity since its recent implementation in some of the walk-in clinics.

"The big thing is that they’re starting it," she said.

[Further reading: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) @verywellhealth.com]

NYC V. Fast Food

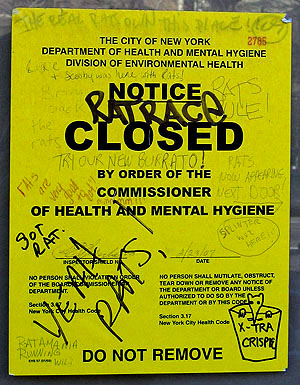

From the moment the footagefrom the infested Taco Bell aired, the rat story had legs. Tourists came to gawk and have their pictures taken at the Greenwich Village restaurant where the large rodents had been seen scurrying across the floor and climbing the tables. Passersby scrawled rodent-themed graffiti on Health Department closure notice ("Gimme a Side of Mice and Beans!"; Try Our New Burrato!"). The rats were "the best local news story you could possibly have," gushed an editor for WNBC. David Letterman made jokes about them on late night television.

Officials at City Hall, however, did not seem so amused. Having rats take over a restaurant was a major embarrassment, especially given that the Taco Bell/KFC in question had passed a health inspection less than 24 hours earlier. The department closed over a dozen other restaurants for health violations since February 23, and city officials have talked up the toughness of its inspection process.

Once again, City Hall seems to be at war with the fast food industry.

Such conflicts have been commonplace during the Bloomberg administration, which takes pride in its aggressive actions on public health. After pushing through a controversial smoking ban, the health department turned to obesity, and the restaurants that it says enable it. It passed rules banning transfats and requiring some restaurants to list calories on their menus.

The issue extends beyond the health department: the head of the City Council's health committee floated a plan to restrict fast food restaurants from opening in low-income neighborhoods, and two Dunkin Donuts franchise owners are suing the city's building departmentfor illegally blocking fast food restaurants from opening in busy places. Still, the rules passed by the Board of Health have attracted the most attention. Restaurateurs and civil libertarians argue that officials shouldn't restrict people from eating unhealthy food, and say that that such attempts to improve public health interfere with the right of restaurants to do business.

Nobody, of course, argues that the city shouldn't clamp down on rat-infested restaurants (well, almost nobody). But some see the same overzealousness in the aftermath of the Taco Bell rat incident that they have in the health department's previous campaigns. Officials shouldn't be so quick to scapegoat restaurants, they say, when the problems of public cleanliness and health extend far beyond their industry.

RATS!

Rats are nothing new to New York City, as anyone who ever waits for a subway or walks at night knows. Like many New Yorkers, they are the descendants of ancestors who came from Europe on a boat, scraping out an uncertain living in the big city. "I think of rats as our mirror species, reversed but similar, thriving or suffering in the very cities where we do the same," wrote Robert Sullivan in Rats: Observations on the History & Habitat of the City's Most Unwanted Inhabitants. "If the presence of a grizzly bear is the indicator of the wilderness of an area, the range of unsettled habitat, then a rat is an indicator of the presence of man."

|

| <fontsize="1.5">The rats at Taco Bell disgusted some, and amused others |

Still, the coexistence is not mutually beneficial. Rats carry diseases, the most famous being the Black Plague. They bite babies. They chew through electrical cables, causing fires. And when they show up in restaurants, it's bound to cause a stir. The stock price of Yum!, the company that owns Taco Bell, has dropped off significantly since it infamous infestation. The record of the city's health inspectors has been suddenly and dramatically called into question. The New York Post pointed out the department's past of corruption, noting a scandal in 1989 resulted in 46 health inspectors– 65 percent of the total force – being found guilty of extortion. The Post doesn't accuse the department of corruption this time, however, but rather of neglect, saying that Commissioner Thomas Frieden has been too focused on changing New Yorkers' behavior, instead of the unglamorous aspects of his job like restaurant inspections.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg defended his record, presenting statistics that showed that 469 eateries had been closed at least temporarily since July 1, 2006, up from 255 for the corresponding period during the previous year. He also said that the department was carrying out exterminationson the block where the video had been shot, and reviewing the restaurants that had been given clean bills of health by the same inspector.

In the days that followed, other restaurants began to be closed down, including several Yum! franchises owned by the same proprietor, and other eateries nearby -- an Au Bon Pain, Risotteria, John's Pizzeria. City Hall has said that there was no crackdown, but local restaurateurs and representatives of the industry charged the department with being overly aggressive in an attempt to offset bad publicity by appearing vigilant. In the weeks since the Taco Bell incident, health inspectors have reportedly closed down restaurants at three times their normal rate.

"They came on a witch hunt," said Michael Frank, a long-time manager at John's Pizzeria on Bleecker Street, while sitting in the empty restaurant last Tuesday, several days after it was shut down. Health inspectors showed up on a busy night, he said, and closed the restaurant for a series of minor violations -- the lack of proper lids on bathroom trashcans, the presence of several holes in the foundation, and the discovery of some mouse droppings in the basement. The staff was forced to kick everyone out during the dinner rush.

In the past, said Frank, the department has given restaurants the opportunity to fix such problems instead of shutting them down immediately. Chuck Hunt, the head of the local chapter of the New York State Restaurant Association agreed, saying that most offenses are generally corrected during the inspection itself, if not soon thereafter.

John's addressed the problems, and was allowed to reopen last Wednesday, almost a week after it was shuttered.

City officials argue that the inspection process works well. The Taco Bell incident, they say, was an aberration. But the controversy has sparked discussion about several long-term solutions to make restaurants cleaner.

The New York Sun's prescription is the most radical. It thinks that City Hall should get rid of health inspectors altogether, cut taxes with the money its saves, and let customers "navigate the tradeoff between price and speed and cleanliness in a restaurant on their own, without the assistance of big government."

Hunt of the restaurant association says inspections are necessary, but would like to see them used as opportunities to educate restaurants on avoiding unhealthy conditions. He also argues that City Hall should rethink its banon garbage disposals at commercial establishments. Critics say it leads to piles of food waste sitting in restaurants until they can be taken away by garbage trucks, and Councilmember Joel Rivera has introduced a bill that would end the ban. He says that he hopes the recent controversy will bring urgency to the measure, which has been languishing.

"It will help to decrease the cost of carting garbage out of New York, which we all know is expensive," he said, describing the impact his bill would have if passed. "At the same time we get to mitigate the issue of rats."

The city's effort to control the rat population is not simply a problem in restaurants, of course. Almost 30 percent of rental housing units are infested, and the city's subway tunnels, old buildings, and abundance of waste makes an ideal habitat for rats. City officials describe a wide ranging campaign to combat the root causes of infestation. There is no perfect way to tell whether the campaign is working, because how do you measure the rat problem. By complaints about rats? They've almost doubled since Bloomberg took office. By the number of times rats bite people? That number is at its lowest level in decades.

Bloomberg claims the number of rats in the city " does seem to be on the decline," but others say the recent controversy proves that the war on rats will never be won.

FATS!

Even clean restaurants can be unhealthy, however. Until several weeks ago, most of the controversy over the health department has centered on its attempts to legislate healthy behavior.

Two rules the Board of Health passed in December to try to make restaurants healthier have set off the latest round in this debate, which first flared up when Bloomberg and Frieden decided to implement a full ban on smoking. In each case, the basic parameters of the debate are the same: On one side are those who laud Freiden as a visionary pushing innovative policies that will improve public health. On the other side are those who argue that he is interfering in areas where people should be allowed to make their own choices, no matter how unhealthy they may be, and hurting business owners in the process.

Trans Fats

Under one of these rules, New York would become the first city to ban the use of trans fats, artificial fats that medical experts say increase the chances of heart disease and other serious health conditions.

Trans fats are used to make crunchier foods with longer shelf lives. They are widely seen as unhealthy, and Freiden says that they can be replaced without affecting the taste or cost of food.

Opponents of the bandon’t claim that trans fats are healthy; they argue that if people want to avoid them they can simply not eat foods that use them. A ban, they say, will harm businesses that will have to change suppliers and recipes. Switching to alternative fats could cost money and change the taste of their products.

But momentum has shifted against trans fats. Fast food chains like McDonalds and Starbucks are phasing them out, and cruise lines, hotel chains, and even shortening brand Crisco say they are also eliminating trans fats. Last week, the health commissionerof the EU said it should follow New York's lead on a trans fat ban.

The City Council initially sparred with Frieden, saying it wanted to introduce its own plan in the form of a law. But Councilmember Peter Vallone recently introduced a bill to simply pass a law codifying the board's plan, making it harder for the ban to be overturned when Bloomberg leaves office in 2009.

Listing Calories

The Board of Health also passed a rule that would require restaurants to list calorie totals next to each menu item in the same size print. Only restaurants with standardized menus that already provide nutritional information will be affected when the requirements go into effect in July 1. Such establishments account for about 10 percent of the city's restaurants, and are mostly chain fast food places.

Restaurants that provide nutritional information already said they were being punished unfairly, and predicted the rule would be an incentive to stop providing any information. They also complained that even with a standardized menu there were too many variations on each dish to list a single calorie count honestly. The board of health argued that it allowed the restaurants to list a calorie range, but critics were not mollified.

In late February several chains including Wendy's and White Castle stopped providing calorie countsso that they would not have to comply with the new rule.

Spurred by the restaurant industry, Councilmember Rivera introduced a bill that would reverse the rule. Instead of requiring restaurants to list the calorie counts on menu boards, Rivera's bill would allow them to use brochures or on posters. Critics say this misses the point, since people will not see the counts when they purchase the food.

As with trans fats, some council members also said the board should submit its ideas as legislation

"This is a major policy change," said Councilmember David Yassky, head of the council's small business committee. "To do it administratively without the democratic process and a council vote is reason alone to oppose it."

Council bills generally do not pass without the blessing of the speaker, however, and Quinn has indicated she will not support the council's pushing back against the board on the calorie bill.

"I don't have any particular interest in changing what the Board of Health has done," she said.

Despite the controversy, there is no guarantee that the recent steps by the city will actually improve New Yorkers' health. Many remain skeptical that these seemingly intractable problems are going to disappear because of anything the Bloomberg administration does.

If listing the amount of calories in foods led people to make better choices, then Americans would have gotten healthier in the years since rules were put in place requiring packaged food to list nutritional information, said Hunt. Instead, Americans have gotten fatter. Michael Pollen, author of The Omnivore's Dilemma, sees the vilification of trans fats as only the most recent in the ever changing landscape of nutrients falling in and out of favor. Trans fats were actually introduced as a health alternative to saturated fats; today, the labels of foods containing saturated fats proudly proclaim the contents to be free of trans fats.

And as for rodents, well, few really see a future without them. Rats can be chased out of buildings or even blocks, but no one believes the city will ever be rid of them. The windows of the now-infamous Taco Bell are boarded up now; there's nothing more to see. But one vandal has offered some advice for latecomers hoping to catch a glimpse:

"Rats Now Appearing Next Door --->" Â

In Danger: Men At Work

Joseph Endico doesn't remember the sound of the rope snapping. He doesn't remember seeing his harness give way, or feeling his head hit the ledge of the window as he fell three stories from the collapsing scaffolding onto the grass below.

"I remember waking up on the ground a little while later with a towel on my head, and people saying, 'you're going to be okay,'" Endico recalled recently, the scar from the metal staples used to close his wound still visible on his shaved head 19 months later.

Endico did survive and discussed the accident matter-of-factly as he sat in his lawyer's office last week. But he is not okay. Still unable to return to his job, Endico is living off of workers compensation, with the help of his family.

He says he had never heard of another scaffolding accident before his own, but that since his fall he notices them everywhere. Its not just scaffolding: The most recent statistics count 29 construction related deaths in the city in the year leading up to September 30, 2006, a 60 percent increase from the 18 deaths the year before.

In recent weeks public officials have taken several steps responding to issues of workplace safety. Councilmember Erik Martin Dilan introduced three bills specifically related to scaffolding safety, following up on a mayoral taskforce. Governor Eliot Spitzer, meanwhile, announced a plan to reform workers compensation so that it better serves both injured workers and their employers, a balance that has evaded state policymakers for years.

MORE CONSTRUCTION, MORE DANGER

New York City's construction industry has become increasingly dangerous as the city experiences an unprecedented building boom. The city is issuing residential building permits at near record numbers, and huge projects are being planned and constructed around the city. (See slide show.) About 123,000 New Yorkers work in construction, according to the New York Building Council, and the number of construction jobs is increasing so rapidly that employers worry about finding enough workers to fill them.

As the industry expands, its composition is changing. About half of the construction workers in the city are immigrants, and over one-quarter are not proficient in English. 75 percent of New York's construction jobs remain unionized, four to five times the national average. But with so much construction going on, the number of smaller non-union employers is growing.

It is non-unionized immigrants working on smaller jobs who are being injured in disproportionate numbers. Over half of the deaths over the most recent year involved companies with fewer than 10 workers, and almost three quarters of those killed were immigrants or workers with limited proficiency in English.

Unionized employers take this as a sign that their fly-by-night counterparts working smaller jobs should be subject to stricter regulations. Larger construction sites are subject to more stringent safety regulations. Any construction project with buildings over 14 stories tall must keep a site safety coordinator on site at all times, for instance, and companies building scaffolding over 40 feet tall must apply for a building permit. Lou Coletti, head of the Building Trades Employers' Association, an organization that represents union employers building large projects, says that city officials would do best to extend safety requirements to smaller, non-union employers.

"We know our members do it because we invest $50 million a year," he said. "The non-union sector invests nothing."

Non-union immigrant workers are at the highest level of risk

SAFER SCAFFOLDING

Construction is a dangerous job, and workers at or below street level are hardly immune to danger. A construction firm on Staten Island, for instance, pleaded guilty to negligent homicide last month after one of its workers was buried when the trench he was working in collapsed. But city officials are paying special attention to falls, particularly those relatd to scaffolding.

Falls are the most common cause of construction deaths in New York. Locally, such deaths rose from nine to 17 over the last year. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg planned City Hall's response to the increase in construction deaths, his first target was hanging scaffolding. His administration formed a task force to establish tougher regulations and has adopted the recommendations it made in December.

Acting on these recommendations, the mayor has included $4 million in his budget for the upcoming year to create a scaffolding safety unit in the buildings department with 10 new inspectors to enforce existing safety regulations. Another $2 million will be used for training and outreach in Spanish, Chinese, Polish, Russian, and Urdu.

Councilmember Dilan, a member of the task force, introduced three bills that would make several aspects of its recommendations city law. They would require construction firms to notify the buildings department when they plan to use C-Hook scaffolding, a type of hanging scaffolding involved in over half of the scaffolding deaths in 2006. His bills would also increase fines for violators, and require daily written inspections of scaffolding by site supervisors.

The mayor also called on the federal government to increase its investment in local Occupational Health and Safety Administration inspectors. This echoes criticism from worker advocates who blame the lax approach of Bush administration for the fact that 2004 was the first year in a decade in which the nationwide workplace fatality rate actually rose. In its first five years in office, the administration "failed to issue any significant safety and health rules, compiling the worst record on safety and health issues in [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] history," according to the AFL-CIO report Death On The Job.

New York State fares better than most others, ranking ninth best in terms of worker fatality rates and imposing harsher fees on violators. Even so, the AFL-CIO calculates that if federal inspectors in New York continue their work the current rate, it would take 99 years for them to visit each workplace once.

Joel Shufro, executive director of the non-profit advocacy group New York Committee for Occupational Safety and a member of the task force, doubts Bloomberg's calls for help from Washington will change this.

"[The mayor] would have to be demanding a different administration with a different philosophy of enforcement," said Shufro. "This one, in terms of safety on the job, is bankrupt."

AFTER THE FALL

Even for construction workers who survive, accidents on the job often change their lives forever. Joseph Endico had been working on construction sites for decades, and on scaffolding almost daily for the three years leading up to the morning of June 24, 2004, when he was asked to help install rubber waterproofing on the third story of an apartment complex. There was a harness waiting for him on the scaffolding as well as a rope grab, which serves as a backup if the harness fails. He put them on.

During the part of the morning that Endico doesn't remember, one of the frayed ropes holding up the scaffold he was standing on gave way. His harness and rope grab failed in succession, and he fell three stories, hitting his head on the way down.

The fall left him with a concussion, as well as serious injuries to his back and neck. After a night in the hospital and six weeks at home in bed, Endico started a physical therapy regimen that continues today. He recently had surgery on his shoulder.

The benefits that workers like Endico are entitled to, and what legal recourse they can take against their employers, have been perennial sources of tension at the state level, where much of the regulations regarding injured workers are written.

Today, Endico's only income is workers compensation, a benefit that he will continue to receive as long as he is unable to work. Workers advocates and employers alike have long complained about the state's program. The $400 Endico receives weekly is the maximum benefit, even though in his case it is about half his previous salary and does not include health insurance. Despite the relatively meager payouts, employers put more money into the program than almost anywhere else in the country.

Bit despite such failings, changing workers compensation has long been bogged down in Albany. On the last day of February, however, Governor Eliot Spitzer announced a deal on workers compensation that he and other state officials brokered with labor and business leaders. The agreement increases the maximum benefit to injured workers, but caps the amount of time they can spend on workers compensation, while also taking steps to cut down on fraud. Spitzer estimates it will save $500 million a year, resulting in 10 to 15 percent lower premiums for employers.

Unrelated to the recent changes to workers compensation is a controversy over lawsuits involving those hurt on the job. Recipients of workers compensation are not allowed to sue their employers. State law grants an exemption, however, to those who were hurt in falls. Under this law, employers whose workers operate at heights are liable for safety and cannot pass that liability on to subcontractors. Lawyers and advocates representing injured workers believe this law saves lives by holding employers responsible. Employers are also not allowed to argue that the workers own negligence caused an injury. For over a decade, employers groups have been trying to get Albany to repeal it, saying it raises construction costs and penalizes employers for workers' mistakes.

"The employers hate it, hate it, hate it," said Shufro, "and the lawyers love it, love it, love it."

Endico is suing his employer, Electchester Third Housing for damages under this law. A lawyer for Third Housing declined to comment on the specifics of the case for this article.

Endico said that he would like to see safety inspectors present on all work sites at all times. He believes it is probably too late for him, however, since his injuries will probably keep him from ever returning to a construction site. Even if he were physically able, Endico has developed a newfound fear of heights that would keep him from the kind of work he had been doing all his life.

Today, even climbing the ladder to clean the gutters at his Throgs Neck home seems like too much for Endico. He asks his nephew do it for him, instead.

"I wouldn't go up no more," said Endico when asked about returning to a construction site. "I counted on my harness. What would you count on? It might fail again."

Â

Charting New York's Health

Many New Yorkers apparently have been keeping their new year’s resolutions to live healthier lives. And their resolve has produced results. The city health department recently released figures showing that New Yorkers are living longer than in the past -- and longer than Americans as a whole. A child born in the city in 2004 can expect to live to be 78.6 years old -- almost 10 months more than a child born in 2001.

The information came in the city government’s Annual Summary of Vital Statistics , one of the many measures of New Yorkers’ health that the Bloomberg administration, which has made public health a priority, compiles and releases.

Included among these are the Community Health Profiles. Visitors to the department Web site type in a ZIP code to be directed to a pdf file with an array of numbers and facts on their neighborhood, including rates and causes of premature death, how their neighbors assess their own health, the percentage of community residents who smoke and so on. And the profile compares the specific community to the borough and to the city as a whole.

The health department considers these profiles an important tool in figuring out where health problems exist, in establishing programs to address those programs and in helping New Yorkers take better care of themselves.

Cari Olson, a master of public health and the lead author of the report, spoke with Gotham Gazette about measuring health in New York City.

A HEALTHIER CITY

Gotham Gazette: What conclusions can we draw from all the information in the Community Health Profiles?

Cari Olson: Although, overall, we see great improvement in the health of New Yorkers, there are still major health differences between neighborhoods. If you look at the HIV-related death rate in New York City overall and in every single neighborhood, it has dropped dramatically in the last 10 years. It’s an example of New Yorkers, public health professionals and others working together to improve health. At the same time, if you look within the borough of the Bronx, the Highbridge-Morrisania death rate is 10 times the rate that’s found in Riverdale. [Morrisania had the highest numbers of deaths from AIDS in the city.] Clearly there’s a differential in how health is being taken care of between those two neighborhoods.

|

|

|

Morrisania had the highest numbers of deaths from AIDS in the city.

|

|

One of the reasons that we did these profiles is we wanted to be able to characterize neighborhoods -- not to stigmatize anybody, but to say this is where we have challenges and we all need to work on doing something about that.

Gotham Gazette: I would imagine there is a pretty stark income difference between those two communities. Does one see that in general -- that in poorer neighborhoods you have higher rates of preventable deaths, premature deaths and other health problems than in more affluent areas. Or is it not that clear cut?

Cari Olson: A very complex set of factors dictates why we see certain disparities between neighborhoods but absolutely one big piece is income and neighborhood resources. When the first profiles came out, one of the things that the Department of Health did was use them to identify the three areas of New York City where we were seeing the highest burden of preventable illnesses. Those three areas are the South Bronx, Central and East Harlem, and North and Central Brooklyn. In those neighborhoods, the department created a district public health office that could work directly with the people who were already working hard on health issues at the neighborhood level.

With the new profiles, we saw improvements in those neighborhoods as well as others, but we still see that those neighborhoods and the people living there are facing the biggest challenges. Income and the resources available are definitely a part of that.

HEALTH AT THE NEIGHBORHOOD LEVEL

Gotham Gazette: How did these profiles come about?

Cari Olson: We did the first community health profiles in 2003. We were trying to provide data on the health of New Yorkers so they could understand how health looks at the neighborhood level. If you live in Chelsea, you’re going to have different health concerns than if you live in Bay Ridge.

These 2006 profiles are the new and improved version. We have more statistics, and we’re using the “Take Care New York” priorities that are established by the New York City health department. These are the 10 areas of illness and disease that are causing the most health problems for New Yorkers and are the ones we can do something about, that are amenable to change.

In these new profiles, we provide time trends. People can not only compare their neighborhood to the borough and to New York City overall, but they can also see how health has changed from 1995 up through 2004.

Gotham Gazette: How do you put these together?

Cari Olson: It’s actually a lot of fun. We take a lot of different data sources. We use the Community Health Survey that we do every year. We call up 10,000 New Yorkers and ask them a lot of questions about their health, their access to health care, and preventative health things that they’ve done for themselves. We ask them, “Do you have a regular doctor?” “Do you have health insurance?” “What’s your height and weight?” We ask them whether or not they’ve gotten cancer screening. We ask them about sexual behavior, about using condoms, about getting HIV tests.

Another source is in-patient hospitalization records from the New York State Department of Health. We have the record of every single hospitalization of any New Yorker anywhere in New York City.

|

|

|

The Rockaways had the greatest number of deaths from heart disease.

|

|

We also have vital statistics data. That includes death, or mortality data, and birth data from death certificates and birth certificates. We can use those data to look at the different causes of death in New York City. The same thing with births. We can see whether women are getting pre-natal care and where they get it, look at births to teenagers, things like that.

Gotham Gazette: These profiles are divided in 42 communities. What do those 42 areas reflect?

Cari Olson: We use the United Hospital Fund neighborhoods, created by the United Hospital Fund, which is a non-profit organization in New York City. They are aggregates of ZIP codes and were created to as closely as possible reflect neighborhoods that New Yorkers think of as being neighborhoods.

A lot of people ask us, “Why didn’t you use community boards,” or City Council districts? The issue with that is that a major source of our data is surveys. If I call someone and ask, “What council district do you live in?” how many people do you think would be able to tell me? Pretty much nobody. But everyone knows their ZIP code.

MORE OBESITY, LESS SMOKING

Gotham Gazette: You mentioned earlier that overall we’re a healthier city. But there has been a lot of discussion of the increase in obesity and diabetes. What do these profiles tell us about that?

Cari Olson: One fifth of all New Yorkers -- 20 percent -- now are obese, but the percent of obese adults differs between New York City neighborhoods. For example, about one in 10 adults on the Upper East Side and in neighborhoods like Grammercy Park and Murray Hill are obese. That’s compared to about three in 10 adults or 30 percent in East Harlem and in East New York [which has the highest rate].

We see obesity going up across the city, regardless of neighborhood, but also we see disparities between neighborhoods. It’s something we really want to focus on because heart disease is a huge issue for New Yorkers and for the United States. [The Rockaways had the greatest number of deaths from heart disease.]

We hope that all of the work that’s been done, particularly in the area of smoking and more and more in the area of exercise and obesity, will make a dent in this. It’s definitely a big issue and something we want individuals to be focusing on.

We want to help provide people with the things that will contribute to their health. We can say you need to exercise and eat healthy foods, but if you don’t have a safe and affordable place to exercise and you don’t have a place to buy fruits and vegetables, then that’s a problem. Those are the kinds of things that we’re trying to create.

In Harlem, we’re doing programs around the bodegas. They also have exercise programs and have started walking clubs and things like that -- trying to help give people options to do the things that will help improve their health.

I can’t emphasize enough how much we depend on our partners in the community, not just non-profit organizations and other programs, but also individuals. This is something we have to do together. We also need to partner with people so that we can make health better.