The Heroes Of 9/11 Are Getting Sick

Detective James Zadroga was inside 7 World Trade Center on the morning of September 11, 2001. He escaped –- barely –- when the building collapsed. But Zadroga could not escape the damage done to his body by the hundreds of hours he spent at Ground Zero cleaning up the rubble in the following weeks. On January 5 of this year, Zadroga died from lung disease and mercury poisoning – a condition that hasn't been a widespread occupational hazard for over a century when hatters were sickened as they dyed beaver pelts.

Working at Ground Zero seems to have been even more dangerous than initially suspected, say health researchers. At least two Ground Zero rescue workers besides Zadroga –- and maybe more than twenty -– have died from illnesses that seem to be related to working on "the pile" (rescue workers' nickname for the rubble of the twin towers). But James Zadroga's death in particular has redirected attention to a problem that, experts say, will likely continue for decades.

Efforts to confront the health effects of 9/11 have not progressed quickly. Federal attempts to determine how far dangerous chemicals spread have sputtered along, enraging many local residents and environmental activists, who suspect that the towers' collapse spread contaminants across lower Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn. A registry set up to collect data on health trends covered a more limited area, and there is currently no way of knowing how many people are sick with 9/11-related illnesses.

The approximately 40,000 rescue workers are probably the one group at greatest risk, because those who worked on the site were directly exposed to these chemicals at very close range for long periods of time. Zadroga spent 470 hours at Ground Zero. But as they get sick and even die, public officials have had little success tracking their health, much less treating them.

This month, the New York congressional delegation called on the federal government to appoint a 9/11 health czar, whose first responsibility would be to find a way to track and confront the health problems rescue workers are facing. Until that happens, private screening and treatment programs are struggling to do what they can.

MONITORING AND TREATING PROBLEMS

Vincent Forras, a volunteer firefighter from Westchester County, was dispatched to Ground Zero immediately after the attack. He ended up working on the site for three weeks, spent two hours buried alive in the rubble of the South Tower, and later received the Ground Zero Service Medal.

Rescue workers had difficulty breathing soon after arriving at Ground Zero, said Forras. So, he said, "they juiced us up with all kinds of Albuterol and various medications to keep us breathing." This allowed rescue workers to continue working on the pile, where they filled their lungs with lead, mercury, asbestos, and pulverized cement and glass.

When Forras breathes now, he feels like he is "drowning in air."

He lists his other problems: He has "World Trade Center Cough", a symptom of Reactive Airway Dysfunction Syndrome. He is producing too much phlegm, has massive headaches, sinus problems, and symptoms of heart disease. More than four years after 9/11, his wife is still picking pieces of glass out of his skin.

Forras had his problems diagnosed at Mt. Sinai's World Trade Center Medical Monitoring Program, run through its Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine. This program has screened the health of 16,000 men and women who worked on the pile, and is the largest effort to monitor the health of rescue workers at Ground Zero. The screening program is federally funded, and is open to anyone who worked at Ground Zero, whether they show symptoms or not, with a few exceptions: New York City firefighters – who have their own monitoring program – are ineligible, as are federal workers. Federal workers currently have no options for screening or treatment.

About half of the people that have come to Mt. Sinai for diagnosis have respiratory diseases, sinus or throat problems, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Dr. Robin Herbert, who is the director of both the screening and treatment programs, continues to be taken aback by the severity of the medical problems like those afflicting Forras. She also feels overwhelmed by the problems involved with getting treatment for those her program screens. Mt. Sinai refers people who need treatment to its own program, which is overburdened, and has managed to see only 1,800 patients. It doesn't have the resources to see any more.

Private philanthropists currently provide all the money for treatment. The Red Cross gave $20 million to fund several such programs, and the lion's share of the Mt. Sinai's program comes from this pool of money (though donations like the $100,000 it received from a church group in Ohio, or $2,000 worth of pennies raised by children in Queens also help).

Mt. Sinai estimates that 5,000 people it has diagnosed as sick are not getting necessary health care. "It's pretty consistently the case that demand has tended to exceed our capacity," said Herbert.

WHERE IS THE GOVERNMENT?

The Red Cross sees its role as a stopgap measure, operating only until a more systematic public program can be put in place. It will stop its funding next year.

But interest from government is underwhelming. In his State of the City speech this month, Mayor Michael Bloomberg mentioned major plans for Ground Zero and for health care. He did not, however, connect these two themes. New York State government has provided treatment for those who worked on the pile with access to its worker's compensation program -– even if they came from out of state -– but its resources are limited.

It is the federal government's inactivity, however, that has most angered those involved with providing health care to 9/11 rescue workers.

There were 10,000 federal employees among the rescue workers at Ground Zero. The federal government set up its own medical monitoring program for these workers, but closed it down after screening only about 400 people. Federal employees cannot seek help through other programs; instead, they must wait for this program to be restored.

If the federal government has been lackluster in screening for health problems, its treatment program is nonexistent. To date, no federal money has been dedicated to treatment for any 9/11 rescue workers.

Some lawmakers in Washington are trying to change this. In December, Congress restored $125 million for funding for 9/11-related health issues that the Bush administration had cut from the budget. New York State's workers compensation program will get $50 million, with the remaining $75 million spent on existing monitoring and treatment programs. For the first time, this money will be available to be used not only to monitor workers' health, but also to treat their problems. It is not yet clear, however, when it will reach those who need it or how it will be split among monitoring and treatment programs.

On January 25, the New York Congressional delegation sent a letter to federal Health and Human Services Secretary Michael Leavitt asking him to appoint a "9/11 health czar" (letter in pdf format). So little has happened, they argue, because there is not a single person who is directly responsible for addressing 9/11 health issues.

Representative Carolyn Maloney and Vito Fossella recently called a press conference at Ground Zero to push for the idea. A position should be created within the department of Health and Human Services whose work would start with the establishment of "an exhaustive medical screening, monitoring, and health care program for all responders exposed to the toxins," said Maloney, encircled by men and women in fire department jackets or hats from local ironworkers unions. One had lost half a foot; another had lost almost a third of his lung capacity.

After Maloney finished, Forras stepped forward to talk about his battles with daily treatments, and about his feeling that the care he needed wasn't out there. He fully expected to die, he said, "sooner than later."

"I can guarantee you than when we come back here next year, some of these people will not be standing here," he said of those surrounding him. "You will find shadows of people."

Â

The Need for Healthier Schools

Most people think all asbestos was removed from New York City public schools years ago. So participants in a New York State Assembly hearing on healthy schools earlier this year were shocked to learn that last year construction workers who were replacing a gym floor at P.S. 219 in Brownsville, Brooklyn inadvertently released the flaky white substance throughout the building. The school was shut down immediately for an emergency cleanup. Student and faculty health was jeopardized, and valuable learning time was lost.

The legislators were even more shocked to learn that no one knows how many other New York City school buildings still contain asbestos; records at the Department of Education are incomplete.

At the Healthy Schools Network, our files are filled with reports from parents and teachers who are struggling to deal with unusual and unnerving illnesses affecting their children, students and coworkers. But it is not possible to do a scientific study to see if environmental conditions in their schools are at fault. The data is simply not available; neither city nor state officials keep track. But ignoring the problem will not make it go away.

ILLNESSES AND ABSENCES

Students spend nearly a quarter of their waking hours in school buildings that parents trust are safe. Unfortunately, there are real reasons for concern in many public schools. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has said that environmental health hazards like mold infestations, toxic chemicals, diesel fumes and contaminated renovation debris, along with other pollutants such as pesticides and toxic cleaning and maintenance products, can foul a school’s indoor air quality. In fact, the EPA estimates that about half of the nation's schools have poor indoor air, a major health hazard. In the winter, as schools shut their windows and children spend more time indoors, the problem becomes even worse.

In New York City, the state Assembly heard testimony from Avril Dannenbaum, whose seven-year-old son attended PS 111 in Manhattan. He has a chronic infection that compromises his immune system. His mother says she can manage his infection and his seasonal allergies at home. “But then,” she explained, “if you add on environmental allergens in his school, such as a dirty rug to sit on, peeling, flaking paint from the walls and window sills, along with industrial cleaning products and insecticides, you have a child who comes close to shutdown. Then he is unable to learn or function in class.”

While many problems afflict older schools, new ones are not immune. Tests found high levels of two chlorine solvents at a new high school in the Soundview section of the Bronx, hastily constructed in an old Loral Electronics factory. Both are known to cause serious ailments, including cancer. Assured by authorities that the vapors were below threat levels, parents later found out that city tests of soil and ground water at the site had revealed serious lead, mercury, cadmium, and chromium contamination.

A PROBLEM IGNORED

With parents, the press, and the political establishment all demanding tougher academic standards and higher test scores, physical conditions in the schools tend to be ignored. Proposals abound for how the city might spend the billions it is owed under the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit, but none of them includes any mention of using some of the money to make schools more environmentally healthy.

These health policies and practices have a direct impact on academic achievement and efficient allocation of education funds for every child. Poor environmental conditions in schools sicken students, teachers and staff, and inhibit academic performance. And our neediest children also need the healthiest schools. Poor school facilities contribute to a poor leaning environment that can undermine children’s health, attendance and test scores.

The American Lung Association, along with the federal Centers for Disease Control and the EPA, agree that asthma is the number one reason for school absenteeism due to chronic disease in New York’s schools. The city has some of the worst asthma rates in the nation, and the disease is epidemic in many neighborhoods, especially communities of color and among the poor. Public health officials studying urban asthma think a cleaner classroom environment could help control the crisis.

CLEARING THE AIR

There is some good news to report. Coal boilers, which remained in some New York City schools for more than 20 years after they were outlawed in other facilities, have now all been removed. In 1999, the state Education Department issued minimal standards and procedures for school indoor environmental quality and health and safety. State legislation has banned arsenic-infused pressure treated wood (commonly used in playground equipment), pesticide-laden cake toilet deodorizers and elemental mercury (a potent neurotoxin) in schools. Schools must now provide notification when they plan to apply toxic pesticides.

In August, Governor George Pataki signed legislation requiring schools to use environmentally preferable (green) cleaning products. The state Office of General Services already does this for state facilities, so the healthy products are readily available. Reducing student and staff exposure to industrial strength chemicals will help reduce school absenteeism. The program will take effect with the start of the September 2006 school year.

Both the city and state are moving toward implementing guidelines to assure that all school construction and renovations meet high standards for health. In New York City, a broad coalition of environmental, labor, health and healthy schools advocates were pleased when the City Council passed a green building standards bill earlier this year and Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed it into law in October. This significant legislation requires that all public construction, including schools, meet standards for environmentally friendly – or green – buildings by January 2007. By requiring better ventilation and barring the use of toxic paints, carpets and other materials, this measure will help improve student health and performance.

WHAT MORE CAN BE DONE

Now it is time to take further steps. Fortunately, protecting our children will not add billions to the cost of education.

At the federal level, Senator Hillary Clinton secured amendments to the 2002 No Child Left Behind law, which for the first time defined healthy and high performance school standards in federal law. This legislation required a comprehensive federal study of how school environmental quality affects student health and learning. But Washington’s follow-through has been flawed. The report, which was produced last year, has yet to be released to the public. Clinton’s initiative also established a grant program for states to spur the development of healthier schools. Unfortunately, Congress has neglected to fund this despite intensive advocacy by the National Coalition for Healthier Schools (in .pdf format), a coalition of over 300 organizations and individuals led by the Healthy Schools Network.

New York State also needs to do more. Albany offers a Green Building Tax Credit that gives incentives to commercial developers to design and construct green buildings, but the credit is not available for schools. Pataki has signed an executive order that requires all state public construction to meet the standards of the Green Building Tax Credit. But while the state recommends that schools meet those standards, it does not require them to do so. That should change.

And the state should move ahead on initiatives already in the works, such as a joint project of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and the State Education Department to develop healthy and high performance school design standards. The legislature should pass a bill introduced by Senator James Alesi and Assemblymember Steven Englebright that would require healthy and high performance design standards for all New York schools.

For parents, teachers and school staff, such improvements cannot come soon enough. As Avril Dannenbaum told state lawmakers about her child, “I can make his home as safe as possible, but it’s at school that he needs to be able to function well to learn optimally. I’d like you to make his school a safe place where he can study and reach his full potential.”

Stephen Boese is the New York State director of the Healthy Schools Network

Image above (photomodified) from The Texas Department of Health

Â

Without Health Insurance

A woman from Pastor Ebenezer Martinez’s church was recently bit by a dog, and ended up spending a week in the hospital. Neither the woman nor her husband had health insurance, and they were worried about the thousands of dollars of medical bills. Martinez is not sure how to help her, or the many others among his South Bronx congregation he knows don’t have insurance. But he does know what they’re going through: He is not covered, either.

Martinez, 54, gave up what he refers to as his “secular job” as a counselor at the Upper Manhattan Mental Health Center two years ago, when he left to become the pastor at the First Pentecostal Church of Jerome Avenue as its only full-time employee. Knowing that the church was not in great financial shape, he hid his medical condition –- he has high blood pressure -– from the board of trustees, so it wouldn’t strain to pay for health insurance. Martinez gave up his prescription drugs, instead taking aspirin when he felt pain in his chest or arms.

“Using aspirin is not the same, but you know, aspirin helps a little,” he said. The prescription "was very expensive.”

Aspirin was not helping enough, however, and Martinez ended up in the emergency room for nosebleeds he couldn’t control. The trip cost him $700, and he still left without a prescription.

Stories like Martinez's are common in New York, where almost a quarter of the population lacks health insurance. True, the percentage of New Yorkers without insurance has been dropping in recent years, largely due to a unique statewide program that allows community groups to sign New York residents up for Medicaid. But health care advocates fear that within a few months this program will end, and the gains that have been made will be reversed.

Public officials are aware of the growing anxiety among New Yorkers. Mayor Michael Bloomberg made a campaign promise that within the next four years virtually every child in the city would have health coverage. The mayor and the city council are also pushing separate efforts to encourage – or force – private employers to give their workers health insurance.

But as it stands today, huge problems remain. People of color are much more likely to be uninsured than whites, aggravating racial disparities in health care. And experts and officials worry that having a large uninsured population is undermining the financial stability of the health care system as a whole.

“From a health care system’s point of view, the uninsured are the single largest structural flaw in the system,” said James Tallon of the United Hospital Fund.

On an individual level, the lack of having health insurance is often devastating financially. Other times it is far worse. Manny Lanza learned that he had a serious brain condition, AVM, after he had a seizure in 2004, and was referred to St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital for treatment. But for months, the Manhattan hospital reportedly refused to provide care for him until he had insurance. His family labored to get him enrolled in Medicaid, but the delay, they charge, was deadly: Lanza died in his bedroom earlier this year. He was 24 years old. After his death, according to the Post, debt collectors for St. Luke's-Roosevelt called the family demanding payment of $42,000.

THE COSTS OF BEING UNINSURED

About half of New York City residents get health insurance through their work, either receiving it as a benefit free of charge or splitting the cost with their employer. Another quarter of the population receives health insurance through a public health plan like Medicaid or Medicare. Funded by various levels of government, these programs are available to the elderly, the poor, and other disadvantaged populations.

But 1.7 million New Yorkers have no insurance at all. Most, like Martinez, are adults working for small employers, the majority at secular jobs like restaurants or hardware stores. Eighty percent of city residents without insurance are either employed or are the dependents of someone who works.

“There are programs for the very poor,” said Martinez. “But people like me are in between.”

People without insurance are less likely to get preventive care. They often wait until their health problems are too serious to tolerate or ignore, and then arrive at hospital emergency rooms. By this time, health problems that could have been easily addressed earlier have become difficult or impossible to treat.

While it is less effective, the health care received by the uninsured is actually more expensive, both for the patient receiving it and the health care system providing it. Because uninsured patients do not have access to the group discounts that insurance companies negotiate for their clients, they pay higher rates, a burden that has become ever less bearable as health care costs skyrocket. Unpaid medical bills are now the country’s most common cause of personal bankruptcy.

Treating uninsured patients also takes its toll on the hospitals that do so. Dealing with a problem once it has progressed to the point that it warrants an emergency room visit is much more expensive than preventive care; and if a patient cannot pay for this visit the hospital is left to pick up the bill. This burden falls particularly hard on the city’s public hospitals, and is regularly cited as a reason for their financial difficulties.

No one has calculated how much it costs to service the uninsured in New York in particular, but a recent nationwide study showed that the country’s health care system would save between $65 billion and $135 billion if all of the patients it served were insured.

TWO SEPARATE SYSTEMS OF CARE

During the course of their education, students at Albert Einstein College of Medicine spend at least two Saturdays at the ECHO Free Clinic in the South Bronx. The clinic, which provides free health care once a week for those without health insurance, stays busy to the point of being overwhelmed, even though it shuns publicity.

“Word of mouth travels fast, especially when you’re talking about free health care,” said Rus Korets, one of the students who runs the clinic.

Students at Albert Einstein often work at private hospitals during the week, and many are struck by how frequently the medical strategies they have learned in school do not apply.

“I remember the first time I recommended giving an expensive drug, because … in medical school we learn the latest thing,” said Sharmilee Bansal, the clinic’s other student coordinator. “The [supervising physician] just looked at me and said, â€Do you know how much that costs?’ You learn there are other options.”

The existence of two sets of options based on insurance status amounts to "medical apartheid," according to a recent report (in .pdf format) by advocacy group Bronx Health REACH. In some hospitals, more than 95 percent of patients have private insurance; in others, 90 percent of patients are either uninsured or part of a public insurance plan.

Of the ten hospitals that see the largest proportion of publicly insured or uninsured patients, nine are city-run. In privately-run hospitals, those with private insurance have access to clinics that those without it do not have, according to the report.

Since 30 percent of African Americans and Latinos in the city don’t have health insurance, as compared to 17 percent of whites, the issue of health coverage cannot be separated from the issue of race, claims Neil Calman, one of the authors of the report. Lack of insurance, he says, is the number one reason that people of color are more likely to lose limbs due to diabetes, less likely to be tested for cancer following abnormal mammograms, and more commonly don’t live long enough to collect social security.

“While there are no longer signs that say â€Coloreds’ and â€Whites’ hanging over the doors of our institutions, nearly the same thing occurs when we discriminate based on insurance,” the report states.

While a systematic shift is the only way to change this, said Calman, there are immediate steps that could be taken at the state level. One is to change the way clinics are reimbursed by Medicaid from the current system, which pays clinics relatively little to treat patients with public insurance; the other is to make sure that hospitals receiving public funding to treat poor patients prove that this money is going directly to those who cannot pay for their own care.

PUBLIC HEALTH PLANS

Between 2000 and 2004, New York State reduced the proportion of its population without health insurance by about two percent, at a time when the percentage of Americans as a whole without health insurance rose about 1.5 percent (although, as recently reported in the New York Times, the percentage of children without health insurance is dropping across the country.) In doing so, New York State dropped below the national average of uninsured residents for the first time in over a decade.

These gains were secured entirely by expanding public health programs. Today, New Yorkers are more likely to be enrolled in public health plans than people elsewhere in the country. About 2.2 million city residents are covered by public plans, one million of whom, the city claims, were enrolled in the last year. This is about 80 percent of those who are eligible. (Of course, while officials cite this as a sign of success, it means that 20 percent of those eligible, or over 500,000 city residents, are not enrolled.)

New York State

Over the past several years, New York State increased the number of people who were eligible for programs like Family Health Plus, and Child Health Plus. It also tapped into private groups like community organizations and Health Maintenance Organizations to enroll people in public health insurance.

The federal government prohibits private groups from enrolling people in public health insurance, seeing a possible conflict of interest. But it has waived this restriction for New York State, making it the only place in the country where so-called facilitated enrollment exists. Health advocates estimate that half of all New York City residents who enroll in public plans do so through private groups.

“We love that people can go into the clinic where they’re getting care and sign up for Medicaid,” said Denise Soffel of the Community Service Society.

Funding public health insurance is expensive for all levels of government. The federal government, New York State, and New York City have all shown reluctance at times to support programs that increase the Medicaid rolls. New York’s legal ability to run its facilitated enrollment expires this spring, and late last month the state applied for an extension. But many worry that the federal government will not be inclined to grant it, and that Governor George Pataki isn’t willing to push for it.

New York City

The systematic planning for public health plans takes place in Albany and Washington. But Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently laid out a plan to encourage enrollment. His main goal over the next four years is to enroll all 214,000 children who are eligible for public insurance but not currently covered. He plans to do this by simplifying the application process. Eventually, he hopes, children’s coverage will be automatically renewed.

It is too early, say health advocates, to assess Bloomberg’s plan; its potential success depends on execution. But several expressed some concern that the mayor did not mention a plan to increase enrollment among adults as well, who make up about 80 percent of the city’s uninsured.

In New York, the relationship of local government to public health insurance is different than elsewhere. Unlike most other states, local governments here have to pay a quarter of their own Medicaid costs. This pulls local governments both ways – wanting to provide health care on the one hand, and to cut costs on the other.

The answer, says Bloomberg, is to get more private employers to provide health insurance, which he believes will “offer working New Yorker more choices and save taxpayers money.”

NEW YORK CITY AND EMPLOYER SPONSORED HEALTH INSURANCE

New Yorkers are less likely than people elsewhere in the country to get insurance through work, and the percentage of New York State residents with private insurance actually dropped between 2000 and 2004 (though not as much as it did elsewhere in the country).

Even for large employers who have enough employees to negotiate favorable terms, providing health care is a financial burden. General Motors says it pays $1,500 for health care costs per car it manufactures – more than it pays for steel. It cites these costs as a major reason for recent layoffs.

|

|

|

Manny Lanza died after unsuccessfully seeking care at the St.Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital.

|

|

Small employers have less money to spend and less room to bargain. As a result, a third of New Yorkers who work for businesses with less than 25 employees do not have health insurance.

First Pentecostal is on better footing financially than it was two years ago, and it has begun paying for Ebenezer Martinez’s prescription and for trips to the doctor. The board of trustees has also offered to split the cost of health insurance with him, and has asked him to find an appropriate plan.

“In this case I’m blessed,” said Martinez. “But looking for the right plan is not easy. They are very expensive, especially in my case because I’m an individual.” The health coverage he looked at so far ranged from $350 to $500 a month.

Bloomberg hopes to ease the burden on businesses by expanding on existing programs that allow small businesses to band together to secure better rates on coverage. But many say that such programs cannot provide full coverage at affordable rates unless the city subsidizes them heavily.

Not all businesses that fail to provide health insurance can plead poverty, however. When St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital turned Manny Lanza away he was working 50 hours a week at a “part time” job at Wendy’s fast food restaurant.

In an attempt to address the problem, the City Council passed the Health Care Security Act, a bill that requires food retailers with more than 25 employees to spend a minimum amount of money on health care for its employees. This bill would not have helped Lanza, however, because it does not cover Wendy’s. Critics say that the bill is a bid to keep WalMart out of the city, rather than a real solution, and complain that it is unfair to a single industry. Supporters respond by saying that the bill is a test balloon, and want to expand it beyond just food retailers. In any case, the mayor vetoed the council's bill, the council overrode the veto, and it now seems destined to be challenged in the courts.

Health care advocates view the city’s plans to expand employer-based insurance as well intentioned but doubt they will have wide effects. Real systematic change, they agree, is out of the city’s hands.

“All of [these programs] are going to do little teeny things that are going to help certain, limited numbers of people. And they’re important,” said Calman. “But there has to be a total, national solution to the issue. All the rest of this stuff is going to be constantly working around the edges.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Health Insurance Coverage in New York (United Hospital Fund)

NYC Uninsured by Community District (Mayor’s Office of Health Insurance Access)

Medical Costs the Number of Cause of Personal Bankruptcy (Health Affairs)

Separate and Unequal: Medical Apartheid in New York City (Bronx Health REACH)

Â

Bird Flu

For all the attention to the bird flu, discussions of its potential dangers are, for the time being, hypothetical. The disease may never spread from birds to any large segments of the human population, or, if it spreads rapidly among humans, it could be in a form that is not fatal. Still, the less optimistic possibilities are already prompting worldwide worry –- and that includes in New York City.

Some of the scenarios being spun if there were ever a full-fledged avian flu outbreak in the city are not reassuring. As imagined recently by several public health experts such an outbreak could kill 300 people each day, leave Grand Central Station and other public spaces completely devoid of people, and require forced quarantine of infected neighborhoods.

“The city would look like a science fiction movie,” said Dr. Irving Redlener of Columbia University’s school of public health. “This would look like an armed camp basically.”

While extreme-sounding, Redlener’s vision of an avian flu pandemic -– a widespread outbreak of a disease whose victims currently consist mainly of birds in Asia -– is not much different from that of the federal government. The worst-case scenario laid out in a plan of action from the Department of Health and Human Services includes riots at vaccination clinics, shortages of food and power, and $450 billion in costs. It predicted as many as 1.9 million American deaths.

New York City is also developing strategies to deal with pandemic avian flu, and believes it is better prepared than most cities to handle an outbreak. Still, a lack of faith in the federal government and unanswered questions about the nature of the disease itself continue to concern local officials.

FEARS CAUSED BY A NEW STRAIN

A disastrous pandemic flu outbreak is not without precedent. There have been three such outbreaks in the last 100 years, the most serious of which, the Spanish Flu of 1918, killed 500,000 Americans and 40 million people worldwide

The current cause of concern is a strain of avian flu called H5N1 that emerged in 1997. The strain is most prevalent in Asia, where the disease is responsible for the deaths of 100 million birds and about 60 people -- the only human cases to date.

The avian flu is more deadly than most flu strains, killing about half the humans it infects. But it is not easily spread. In its current form, the only way to contract avian flu is through contact with the feces or bodily fluids of infected birds; properly cooked meat cannot carry the flu. What worries health experts is the possibility that the flu could mutate so that it could be spread between humans, which might lead to a pandemic on a global scale.

Again, this may never happen. But the possibility is already prompting worldwide action. China has said that it will vaccinate each of its 5.2 billion chickens, one by one; international organizations and governments are developing plans to encourage drug development and identify outbreaks early; and the United States is spending $250 million to help contain outbreaks in other countries before they spread, while also tightening surveillance at its ports.

NEW YORK CITY’S PLAN FOR AVIAN FLU

The city’s Department of Health has been working on its response to avian flu for over a year, improving its disease detection system, running planning exercises involving hospital and other health workers who would be involved in coordinating any pandemic response, and offering free flu shots to see how well it can operate clinics deluged by large numbers of people. It will publish a full plan in early 2006.

As they contemplate their response to avian flu, city officials begin by acknowledging what they cannot do.

City officials will not be able to keep avian flu from entering New York City, said Isaac Weisfuse, deputy commissioner of the Department of Health. “Once it arrives, we can only try to slow its transmission,” he said. “We will not be able to halt it.”

Still, since 9/11, when the city turned its attention to the threat of a bio-terror attack, New York has been building its capability to deal with a major public health emergency.

“Although there is unquestionably a great deal to be done to prepare, the New York region is fortunate to have many aspects of the required preparedness infrastructure already in place,” said Susan Waltman of the Greater New York Hospital Association.

The first thing the city has done is to bolster its ability to identify disturbing disease patterns by improving the system it uses to track diseases like the regular flu. In doing so, the city is attempting to strengthen its relationships with the network of hospitals, clinics, and other health care providers that would also be involved in any response to an outbreak.

Such coordination would be essential, since health experts agree that the city’s hospital system would be overwhelmed by a full-blown pandemic flu. These concerns seem to run counter to the discussion about hospitals taking place on the state level, in which many argue that overcapacity is hurting the finances of New York’s health care institutions.

City Hall is already ruling out some of the more extreme measures that have been floated. City officials have rejected mass quarantine and the widespread use of masks, saying that neither would be effective if an outbreak did occur. Nor is New York City stockpiling drugs, focusing instead on refining the way it will distribute drugs if needed.

In fact, no vaccine for avian flu currently exists, and it is not clear whether Tamiflu, the antiviral drug used to ease symptoms of the regular flu, would have any effect on the disease. For the moment, the city is leaving it to other levels of government and the private sector to develop useable drugs and make them available if needed.

But city officials are also wary of leaving too much in the hands of the federal government, particularly after its performance handling Hurricane Katrina. This feeling of distrust was compounded at a recent city council hearing on avian flu to which both state and federal officials were invited to testify. Neither Albany nor Washington sent a representative.

“We would like to think, and it probably makes us sleep easier at night, that big problems like avian flu outbreaks or epidemics will be taken care of by the federal government. I don't know if it ever was [the reality], and it certainly no longer is,” said Christine Quinn, head of the council’s health committee. “Rightly or wrongly, the burden is going to fall on the cities.”

THE FEDERAL RESPONSE

The federal government does have a $7.1 billion plan to confront avian flu, which deals largely with developing and stockpiling drugs.

The federal plan also calls for state and local governments to develop their own emergency responses to a future pandemic. It provides $644 million to ensure that all levels of government are prepared for an outbreak, and is asking that state governments chip in on the cost of buying drugs in addition to coordinating treatment for patients.

Critics say that the federal government's plan doesn't provide state and local governments with adequate funding to carry out the tasks it has assigned them. "The plan sets lofty goals but largely passes the buck on practical problems," wrote the New York Times in an editorial last week. Weisfuse, of the city's Department of Health, told the city council that "the federal allocation was peanuts for state and local health departments."

FOR MORE INFORMATION

New York City Department of Health Avian Flu Fact Sheet

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Avian Flu Pandemics Fact Sheet

Pandemicflu.gov

White House Fact Sheet on its Pandemic Flu Plan

Department of Health and Human Services Pandemic Flu Plan

Â

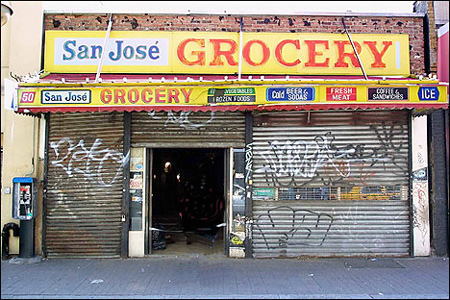

New York's Grocery Gap

The South Bronx feeds the region. Eighty percent of the metropolitan area’s fresh produce and 40 percent of its fresh meat comes through the huge Hunts Point market there. And with the opening of the new Fulton Fish market at Hunts Points last week, the neighborhood will be a leading supplier of fish as well.

| Related Stories in the Community Gazettes: • Growing Food in East New York • Marketing Health in the South Bronx • Small Grocers Survive on the Upper West Side |

But little of that fresh food reaches people in the immediate vicinity. Hunts Point is a wholesale market, off limits to individual consumers. The neighborhood has only one grocery store of any size – making it among the most poorly served communities in the city -- and less than a quarter of its bodegas carry fresh vegetables. (See related story.)

The South Bronx presents perhaps the most glaring example of New York’s food paradox: While the city offers an amazing cornucopia of food – gourmet treats, heirloom produce, food prepared to every religious specification and ethnic taste – some poor neighborhoods lack even a simple medium-sized grocery store. This forces residents to contend with high prices and the unhealthy food. That, in turn, contributes to soaring rates of diabetes and obesity.

FOOD CITY

Food is a multibillion-dollar business in New York City with more than 1,100 grocery stores of at least 4,000 square feet. New York boasts the fresh fish markets and vegetable stands of Chinatown, the Middle Eastern grocers of Atlantic Avenue and icons like Zabar’s. Markets such as Dean and De Luca and Citarella cater to the food obsessed planning to serve Belon oysters, foie gras and truffles on their Thanksgiving tables.

Despite all of that and tens of thousands of smaller delis, greenmarkets and bodegas, many New Yorkers confront what the American Institute of Nutrition has called “food insecurity” – an inability, either because of money or availability, to get safe, nutritional food.“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format) a 2004 survey by City Limits, looked at the number of grocery stores in each ZIP code. If it's not surprising that affluent Soho has the most places to buy food per resident, it is certainly startling to discover that several ZIP codes in Queens, including ones covering parts of College Point and Bayside, have no grocery stores at all. Overall, Manhattan has the most grocery stores per resident; Brooklyn the least.

Despite all of that and tens of thousands of smaller delis, greenmarkets and bodegas, many New Yorkers confront what the American Institute of Nutrition has called “food insecurity” – an inability, either because of money or availability, to get safe, nutritional food.“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format) a 2004 survey by City Limits, looked at the number of grocery stores in each ZIP code. If it's not surprising that affluent Soho has the most places to buy food per resident, it is certainly startling to discover that several ZIP codes in Queens, including ones covering parts of College Point and Bayside, have no grocery stores at all. Overall, Manhattan has the most grocery stores per resident; Brooklyn the least.

“It’s tough to get high quality supermarkets into the â€hood,” Alicia Glenn, vice president of Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, has said. Supermarkets must sell a large volume of goods and so need large amounts of space – perhaps a half a city block.

And some in the food industry predict the grocery shortage could spread to more affluent areas as New York becomes an ever more expensive place to do business. “The better the neighborhood, the less supermarkets there are going to be” because rents are too high, said Morton Sloan, part owner of 10 Associated supermarkets in Manhattan and the Bronx.

Overall, said John Catsimatidis, the owner of Gristedes, the picture is “bleak” for grocery stores throughout the city, largely because of high rents. No one – from Whole Foods to the small mom and pop – is immune to the industry woes, he said, adding, “Something’s got to give.”

LIFE WITHOUT GROCERIES

“When I moved back to Central Brooklyn in 1985, I was struck by its barren nutritional landscape …. The storefront food provision systems themselves – â€bullet-proof’ fast food joints, poorly stocked and over-crowded supermarkets, cruddy, stomach-curdling bodegas – seemed to represent a level of self-destruction and dietary corruption that went well beyond my inability to buy tofu,” writes Mark Winston-Griffith. “Seldom do we consider one of the most basic elements – how an area feeds itself – as a sign of neighborhood well being.”

And many areas feed themselves expensively and unhealthily. In one study (in .pdf format) researchers found that a mango cost 67 cents at Pathmark, 79 cents at Associated -- and $1.79 at an East Harlem bodega.

The high prices are a real obstacle for many poor New Yorkers. Some 2 million people in the city are at risk of going hungry. As many as one in five –- and a quarter of the city’s children –- need help from food pantries and kitchens. This is double the national rate, according to a report by Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum.

But at least the East Harlem bodega had a mango. Many similar stores carry little fresh produce and no fresh meat or fish. In 2004, researchers compared the availability of several foods healthy for diabetics in East Harlem and Upper East Side grocery stores. Only 18 percent of the East Harlem stores had all five of the recommended foods, compared with 58 percent of the Upper East Side stores. And in East Harlem, stores selling unhealthy foods near schools outnumbered those selling healthy foods by almost six to one, according to one study.

HEALTH EFFECTS

All of this takes a toll on health. According to a 2003 study by the city health department, about 8 percent of all adult New Yorkers have been diagnosed with diabetes. With about a third of all diabetics unaware that they have the disease, as many as 12 percent of New York City adults could have diabetes – well about the national rate of 7 percent nationally.

In addition, an increasing number of New York City children are developing what used to be called adult-onset diabetes but is now referred to as Type II diabetes – because so many children now develop it. Doctors blame obesity, poor foods and lack of exercise. “Simple sugars, refined sweets, corn syrups, sodas, vegetables like potatoes and corn, without question, create an unfavorable environment for the pancreas," Dr. Henry Anhalt, director of pediatric endocrinology at Maimonides Medical Center, told the Daily News. He added that meals high in fat and calories, such as a typical fast food lunch, increase the risk.

Almost a quarter of all New York City elementary school students are obese, compared with a national rate of 15 percent. The problem is particularly severe among Hispanic children, more than 30 percent of who are obese.

ATTRACTING SUPERMARKETS

The problem has its roots in the 1950s and 1960s, when many grocery stores followed their middle-class customers to the suburbs. As a result, many who remained in the city had to rely “on small independent groceries that charged high prices and offered minimal variety and corner stores selling a limited selection of processed foods,” according to “Healthy Food, Healthy Communities,” a report by PolicyLink.

Although new stores have entered the city, the problem persists, despite tens of thousands of consumers eager for better food. “It’s not that they don’t want healthy foods or know the value of health foods,” said Kimberly Moreland of Mount Sinai Medical School.

In fact, many people go to great lengths to travel to good grocery stories. “People find a way to get to the supermarket,” said Rebecca Flournoy, a senior associate at Policy Link. “But if you’re going to have to take public transit and you’re on the bus for an hour and a half, and you have two kids with you and six bags of groceries, you’re not going to do it that often.” That makes buying perishable items particularly difficult.

Faced with this shortage, community and health activists, sometimes working with farmers or grocers, have tried to bring healthy food into communities. In some cases, the solution is a supermarket. For example, the Abyssinian Development Corporation and the Retail Initiative joined with Pathmark for a store in Harlem. The project stalled – due largely to opposition from small local grocers – but eventually opened in 1999. Such stores provide many benefits to the community, said Flournoy, including jobs and spurring economic development.

And the stores make money. “We’re pleased with the performance of our urban stores,” Harvey Gutman of Pathmark told Supermarket News. “The fact that we continue to open stores is evidence that we consider them to be successful.”

But, he said opening such stores in the city poses special challenges. “Land is scarce and expensive. Often it needs to be rezoned,” he said. “Opening a store in an urban community involves the participation and involvement of many political and economic entities.”

Rent provides a major barrier. To address that, some have proposed tax breaks for grocers, particularly smaller ones. (See related story.) Sloan of Associated would like the city to provide rent subsidies as well.

PROVIDING HEALTHY FOOD

|

But not every block can support a supermarket or even a medium sized grocery store. And so activists are looking to other ways to improve neighborhood food offerings.

In the Bronx, one effort aims to encourage bodega owners to provide healthier food. And farmers markets and farm stands have become increasingly prominent in the city. The leading effort is the 54 markets run by the Greenmarket project of the Council for the Environment of New York. These greenmarkets feature farmers from upstate, Long Island and New Jersey who come into the city once a week or more to sell produce and farm related products, such as jam and bread. Just Food, a non-profit organization, has sponsored 33 community supported agriculture – or CSAs – in the city. In these buying clubs, residents of an area agree to purchase food on a regular basis from a small farmer. The customers get a guaranteed source of fresh food; farmers get a guaranteed source of income.

Just Food also runs the City Farms project, which works with gardens in the city to distribute what they grow to the community. In 2004, some gardens in the city produced more than 30,000 pounds of food.

Some gardeners sell their wares in farm markets, such as East New York Farms! (see related story) and at so-called urban farm stands. The gardens also donate to soup kitchens and food pantries. “Community gardeners know who needs the food,” said Rebecca Ferguson of Green Guerillas.

The city’s economic health can hamper such efforts. In more depressed cities, says Kathleen McTigue of Just Food, it’s easier to find land to cultivate. Here, she said, “you have to make the most out of small growing spaces.”

But, said Ferguson, the potential in New York remains “massively untapped.” Land awaiting development can be farmed she said, and vegetables can be grown on rooftops and in window boxes.

Some of the available land is returning to an old use. For eight generations, beginning in the 1650s, Wyckoffs lived and farmed in East Flatbush, helping to make Brooklyn and Queens centers of agriculture as late as the 1880s. While Brooklyn will probably never return to its agricultural heyday, area residents are once again farming the grounds of the Pieter Claesen Wyckoff House. And on Sundays in the summer and fall, a farm stand – the kind of thing one expects to see on a back road upstate – sells home grown goods, in the middle of the drab urban landscape – and in front of Brooklyn’s oldest house.

For More Information:

Food Bank for New York City

Green Guerillas

Greenmarket, Council on the Environment of NYC

Hunger Action New York State

Just Food

Northeast Regional Anti-Hunger Network

Articles and Studies

“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format)

Food Redlining: A Hidden Cause of Hunger

Harvest in the City (Earth Island Journal)

Healthy Foods, Healthy Communities

The Hoax of the Food Desert (Ludwig von Mises Institute)

Hunger and Obesity in East Harlem (in .pdf format) New York City Coalition Against Hunger

It’s Just Food (NYU School of Journalism)

Splat (New York) The war between Fresh Direct, Fairway and Whole Food

Â

Providing Fresh Food, and a Sense of Accomplishment

Joanna Willins has sold produce along an East New York Street in 1999. At first she worked alone, but today many other vendors join her under an elevated subway line on the corner of Barbery St. and New Lots Ave, including three upstate farms and 25 East New York gardens who come once a week to the East New York Farms! Farmers’ market.

The number of customers has grown, as well, by about 50 percent a year on average since 2000. The number of customers vary – the market is closed during the winter – but on an average Saturday more than 600 customers shop at the farmers’ market.

Visible from the platform at the last stop on the 3 line, this once overgrown lot is now filled with local residents perusing the variety of fresh fruits and vegetables, which range from multi-colored bell peppers to mackintosh apples to collard greens. Once the customers choose what they need, they reach over the mounds of produce to pay the swamped farmers, and three-quarters pay with the help of a federal food subsidy.

The market serves a population where the rate of obesity is thirty percent and diabetes is fifteen percent - both almost double the city average. Almost half do not graduate high school, and over a third live below the poverty level. By selling food and educating its customers, the market’s organizers hope to improve the health of this struggling neighborhood. They also see themselves forging a sense of community accomplishment.

“Some people in this neighborhood are really struggling to make ends meet, and for families with little time, or who have never eaten well, it's really hard for them to understand the value of what we do." says Georgine Yorgey, the Urban Agriculture Coordinator for East New York Farms! “What we're trying to create for people is really intuitive - you don't have to be a nutritionist to know that eating lots of different kinds of foods, fresh foods, will make you feel better and live a healthier life.”

The market may never be able to provide everything one needs for a complete diet. But then, it offers more than just food. The East New York Farms! Farmers’ market offers its customers nutritional education onsite. Several nutrition educators from Cornell University have a stand at the market with general nutrition info, and a recipe for each week featuring produce from the farmers’ market. They prepare the recipe on a portable burner, and then offer samples to customers. Nutrition-focused nonprofit Just Food also has a stand, where community gardeners do food demos on canning and preserving produce, and making baby food.

“I see these workshops as having a real education role. They're very hands on and practical, not focused on what veggie is in the news today, but focused on the importance of eating lots of different kinds of fruits and vegetables, of eating minimally processed food, and of eating fresh food for your health," says Yorgey.

While some may be interested in the nutritional tutoring, others come because of the government vouchers they get specifically for use at farmers markets. Dess Eparis, an elderly woman, travels for about 20 minutes on the subway to shop at the market. "I come because of the government check I get,"she said when asked why she makes the trip.

These Farmers Market Nutritional Program checks come in addition to the weekly federal WIC checks, which do not allow for the purchase of fruits or vegetables. They are also provided for seniors. In order to receive the checks, recipients need to take a nutritional education class every three months when they go to pick them up. Although small, $20 to $25 a year, they do make a difference. "To some people $20 might not seem like much, but to many around here, $20 is significant," says Tawnya Mercado, one of the market managers.

The federal government is now considering a proposal that would allow the WIC program to address a more complete range of dietary needs by providing checks for fruits and vegetables redeemable at traditional markets

The market also accepts food stamps, but there are some challenges in disseminating the benefits. Food stamps now come in the form of a debit card, and since farmers’ markets are mobile, they need wireless stations. The East New York Farms! just purchased an electronic benefits transfer terminal this year, but there are still glitches in the technology and reception is spotty. Also, many neighborhood residents are simply unaware of the option, "Our challenge at this point is definitely letting all of our potential customers know that we accept" food stamps, says Yorgey.

Beyond benefiting its customers, the market is a boost to the area's anemic economy. The urban farms that provide for the farmers’ market, which are staffed by volunteers, turn a small profit ranging from $5 to $1,000 annually.

East New York Farms!, which runs the United Community Centers Youth Farm, offers paid jobs for a group of local interns. The farm – which stretches a third of a block and produces about 4,000 pounds of produce a season. The 21 interns, spanning in age from 11 to 16 years old, serve as aides to gardeners in the community, help at the farmers' market, and participate in learning activities and workshops. They are paid $5.00 an hour for about 10 hours a week during the school year, and they work more during the summer.

Reflecting on what the interns gain, Yorgey points out that, "One thing that youth often talk about is just the importance of seeing that they can improve the neighborhood through what they do - it's just so concrete to work hard to grow something and then to give it to someone who's going to go home and feed their family."

Many of the institutions and community members involved in the farmers’ market are also turning their attention towards a new cooperative grocery store where community members decide what to sell and what business model to use. The project is being funded by a $1 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, which will also be used to study the effects of the introduction of nutritious food into a previously undernourished neighborhood.

Salima Jones-Daley, a former market manager at the farmers’ market now involved in the coop plans, thinks the coop is a direct result of the farmers’ market. "The community has demonstrated that they want and need more nutritious food to be made available. This coop is the result of that," she says.

The decision of what the coop will carry is to be made at the December 1 meeting of the Food Policy Council - a group made up of local citizens concerned with the availability of nutritious food. The idea is to first choose locally grown, organic foods. Its organizers hope to step in to provide what the market has been unable to give so far – all the ingredients of a healthy diet, served all year round.

Groups -

United Community Centers

Local Development Corporation of East New York

Cornell University Cooperative Extension - NYC Programs

Just Food

Pratt Center for Community Development

Â

City Council District 4 Candidate Debate

On October 18, 2005, three candidates for City Council district 4 debated issues of the city budget, eminent domain, noise, and whether or not Michael Bloomberg is a good mayor. The candidates are: Dan Garodnick (Democrat/Working Families Party), Jak Jacob Karako (Libertarian) and Patrick Murphy (Republican/Liberal/Independence). The event was sponsored by Citizens Union in partnership with the Carnegie Hill Neighbors and Friends of the Upper East Side. It was moderated by Edward-Isaac Dovere from Our Town newspaper.

The following is an edited transcript of the event.

OPENING STATEMENTS

Dan Garodnick:My name is Dan Garodnick, and I am the Democratic nominee for the City Council in this district. I am glad to see so many people here. It is important for us to take interest in our local process. I would like to recognize my opponents who are here tonight. And I want to tell you about my background.

I am a candidate with very deep roots in this district. I grew up here on the East Side. I was born and raised on 20th Street and 1st Avenue in a rent-stabilized apartment where my parents still live in today. My father is in the second row. I am a lawyer with a background in civil rights. I went off to Dartmouth College and University of Pennsylvania Law School. I served as the editor of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review.

I came to New York after college and did civil rights work almost immediately, directing a program in 42 public schools, in every borough in New York City, teaching students how to unlearn stereotypes and teaching them civics. It was a program created in the wake of a racially motivated murder in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. You will remember the Yusef Hawkins’ murder in 1989. We were able to grow this program that taught students how to interact collaboratively in the classroom rather than taking problems out onto the streets. We grew it to 42 public schools.

I also litigated on behalf of fair funding for public schools as part of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit. I represented the Partnership for New York City, the business community here in New York, making very similar arguments as the education advocates, but with the additional piece that failing public schools are also bad for business and bad for the economy.

I represented 13 same-sex couples seeking marriage equality here in New York State, a civil rights struggle which I am very proud to be a part of. I also traveled to down-South to rebuild African-American churches that were burned by arson in 1995 and 1996. I went to religious organizations here in New York City and asked them to sponsor me because I thought it was important for us to respond, to take a principled stand when our neighbors down-South were being subjected to acts of hatred. Central Synagogue agreed with me, and they sent me as a representative, and I spent a month doing that.

I look forward to talking with you about housing, council reform, and the budget tonight, but I share this with you because I want you to know that I am someone who stands on principle. You know where I am coming from and I am going to be a principled representative in the City Council seat. Thank you.

Jak Jacob Karako: This not my first time running. They call me the marathon man among my friends.

One thing that has been really great about this campaign is that I have met a lot of wonderful people. I’ve had a lot of intelligent conversations. And I am really glad that this has happened. I ran in the Democratic primary and I lost again.

I found myself talking less about principles and more about policy, things that I thought people wanted to hear. That is why I ran in the first place. I took the opportunity to come back here, not to be a wedge between the two other candidates, but to speak my mind on why I came to the U.S., and why I think this is the best country in the world despite all of our shortcomings, and why I think we are losing sight of certain dimensions.

I am Jak Jacob Karako and I am the Libertarian candidate. I think Libertarianism is a philosophy that requires a lot of intellectual challenge and understanding. I am still on the ballot. I am running to make a statement on the principles that I would like to make tonight.

Patrick Murphy: I am Patrick Murphy and I am running for City Council. I think this city has come so far with 12 years of mayoral leadership. We have really had a renaissance. But we are at a tipping point again, where we can keep moving forward or move back. We have some serious issues. We have an education system that is only beginning to turn around. We have a looming budget crisis that will decimate what is left of the middle class in this district and the city if we don’t take some steps now to solve it.

I think this mayor has done a great job. He has stood up for principle. He has stood up for what is right. And he has a common sense approach to solving problems. The City Council has its head stuck in the sand. It spends more time obstructing the mayor or not helping him on key things like education reform. And if we don’t get more help in the council, more activist voices, we are really going to be in trouble in the city. That is why I am running, because I think the council needs more independent voices and people who will talk about these issues that are not easy to solve. Some of the problems that we solved in the 1980s and 1990s were much easier. These are difficult decisions that we are going to have to make that impact real lives.

A little background on me: I have lived in New York my entire adult life. I always wanted to live in New York. I moved to a rent-stabilized apartment here in the district -- and have never left the city since 1989. I have been a marketing strategy consultant for 15 years for Fortune 500 companies.

And I am a political activist. I have always stood up for what I think is right regardless of my party affiliation and put principle above party, and I think we need more of that in the council. I have been very involved in the community. I have rolled up my sleeves and spent time at over 200 community board meetings. I am the candidate who has done that. I have met with over 200 community leaders because I think that is the kind of council person we need in this district. It is such a broad and varied district, from Murray Hill all the way to Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village. I look forward to talking with you tonight.

THE CITY’S DEFICT

QUESTION: How do you propose the city address the projected deficit in the city’s 2007 and 2008 budgets? Are there new revenue streams you would propose? Are their specific inefficiencies or wasteful programs that you would seek to eliminate?

Patrick Murphy: This is clearly the most pressing issue that we will be facing in this city. I have spent a lot of time on this issue and looking through some of the recommendations. I think the Citizens Budget Commission, which is truly a non-partisan organization, has the right road map. We are looking at a $3 to $5 billion deficit in the out years. It could be more if have a little blip on Wall Street or in real estate; then we are in even more trouble.

Here is the issue: Budget growth is coming in four areas - current benefits to city employees, pensions, state-mandated Medicaid benefits, and debt, which continues to rise. Debt has gone up $10 billion in the last five years.

Here is what have to do: All of the things that have happened in the private sector in the last 20 years haven’t happened in the city sector. We have got to start moving from a defined benefit program to a defined contribution, 401K. Twenty-two percent of city employees will be new by that time, so we can do that without changing our promises to current employees. We have to start asking employees to pay for health benefits. That has been a challenge in the private sector, but people have done it. That would be a billion dollars right there. My road map is the Citizens Budget Commission’s. This is going to be a very difficult budget.

Jak Jacob Karako: On financial issues, I can’t give you a whole discourse. It would take a few hours to explain why we are expecting to be in deep trouble soon.

One thing we have to do is stop spending. You cannot spend what you do not have. I think that is one thing I learned from my mother -- one can be very generous with other people’s money. Unfortunately, New York City has been very generous in the past. The debt we have accumulated is $50 billion; it is not small change. The whole country of Argentina went bankrupt because they could not pay the debt, $100 billion from their perspective, but what they couldn’t pay was actually about $3 or $4 billion. They just ran out of money. I think that is what is happening.

When you say revenue stream, what is that? I am blaming Bloomberg as much as every one else in this process. There is no additional revenue stream, per se, that is new taxes. You have to increase taxes. That is how you close a budget. You either stop spending money or you increase taxes.

New York City has been on the wrong way for very long time. We have to take some drastic actions.

Dan Garodnick:Next year New York City faces a $4.2 to $4.6 billion budget deficit. In my view, this was precisely the wrong year for the City Council to initiate $200 to $230 million in new spending programs. We need to make sure we get the city’s debt burden under control. We have a $50 billion budget in New York City, $40 billion of which is dedicated to pension costs, Medicaid, debt service, and mandates. And we are getting very close to our debt ceiling.

What we need to do is take a good look in times of surplus, perhaps this even requires a charter amendment in New York City, to take the surplus dollars and apply them directly to debt reduction. This is something that will be part of a long-term process for me as a member of the City Council and as a fiscally responsible Democrat representing this district.

With regards to the question about additional revenue streams, I think that we need to reinstate the commuter tax. This is not within the jurisdiction of the City Council, but it is something I will be very enthusiastic about working with my allies in Albany to accomplish and to make sure we bring back. People are enjoying the services of New York City and not paying for them.

I support congestion pricing, as a way not only to reduce the number of cars on our streets and reduce traffic and congestion, but also to raise money for the right cause.

In any $50 billion budget there is waste and there are inefficiencies. I am someone who is trained as a litigator; I am trained to ask the right questions. And I can perform the oversight powers of the City Council.

REFORMING THE CITY COUNCIL

Q: Do you feel the operation of the City Council is in need of reform? If so, how would you help create a more open, effective, and transparent City Council?

Jak Jacob Karako: First of all, I think 51 seats for City Council is way too many. You can definitely reduce it back to some meaningful number: 10 or 11. An odd number would be better, I guess. That’s number one.

Number two is of course it makes a lot of sense that council members have a little more power, and not toe the line with the speaker. As you know, in the State Assembly, State Senate and City Council the speaker has all the strings. It’s absolutely a must that the members themselves bring certain bills to vote, and that they have a little bit of separation from the speaker.

Dan Garodnick:There are a number of reforms that the City Council needs to implement. One of the things I did when I decided to run for this office was read the rules of the New York City Council. There are a number of things that jump right off the page at you if you read the rules.

One is that in a body of 51 members there are 32 standing committees. That means 60 percent of the members of the body are chairs of committees. In my view that is too many, and it is not conducive to an environment where you can operate efficiently. By way of comparison, the US House of Representatives has 20 standing committees for a body of 435 members; the Chicago Board of Alderman has 20 standing committees for a body of 50 members. And I fully believe in independence from the speaker, and empowering committee chairs, giving them the opportunity to hire their own staffs, giving them the opportunity to have meaningful impact on legislation, but only if you take constructive steps to limit the number of standing committees, because otherwise it doesn’t make sense. I have a package of council reforms, which I’d like to introduce. That’s part of it.

I also think there should be uniformity in mail, between what one member can send to their district and what another member can send to their council district. There need to be very strict timeframes on legislative drafting. There are members who want bills to be drafted, they put them in for legislative drafting services and they never see them again. I think there is a need to be strict timetables. If you are a duly elected member of the New York City Council, whether or not your bill is meritorious at all, you deserve to have it drafted, you deserve to have it heard by a committee or by the council as a whole. I think there are a number of council reforms, and those are just a few of them that I’d like to propose.

Patrick Murphy: I think the way you reform the council is to have more independent voices. We’re going to call the council out on its shenanigans. We’re going to call it out and speak out articulately against its self-dealing. And I’m going to do that, and I’m in a position to that that because that’s what I’ve always done. For example, the council is trying to vote itself an extra term, when the voters voted for [term limits] twice. That’s ridiculous. They shouldn’t be doing it. If they want an extra term, go back to the voters.

They’re going to vote themselves an extra pay raise right after the election -- everybody knows that -- when we’re facing multibillion-dollar deficits. They’re trying to do a runaround of the Campaign Finance Board, and let unions drive a Mack truck through our campaign finance laws. That’s Intro 564-A, which I oppose, but my opponent supports. That would be Dan, not Jack, I don’t know if you’ve taken a position on that.

You need to start calling people out on these things, and you also need to begin to articulate a vision, working with this mayor on things like education reform, talking about the tough things that we’re going to have to do on budget reform. And that’s going to require people who haven’t made deals with the vested interests and the unions that control a lot of this city. That’s how you’re going to do it; you’re going to bring more independent voices who are going to speak out. And you can use your power in the council with the bully pulpit. People listen.

And that’s something that Citizens Union started five years ago in Albany, and it’s beginning to snowball. That’s how you’re going to do it; you’re beginning to try to do it in City Council as well. And I pledge to stand right with you and do that starting in 2006.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION

Q: This is a question from the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts. We have been working for many years to landmark important examples of modern architecture on the Upper East Side. What are your thoughts on the preservation of modern architecture?

Dan Garodnick:The Upper East Side has 125 landmark buildings and six historic districts. As someone who has lived in Manhattan and lived on the East Side my whole life, I understand, respect, and cherish these landmark buildings and these districts, recognizing that these are some of the most valued sites in America. When you consider landmarking additional buildings, this is something I would be a very eager participant in, bringing the community along with the preservationists to make sure it is done in a reasonable and sensible way.

I do not feel constrained by the idea that modern architecture does not deserve landmark status. I think there are a number of buildings which very likely do. I think one of the appropriate ways to handle this is to do a survey right off the bat. I would like to work with the preservationists in the district to take a look and see which buildings qualify, which buildings might qualify, and put them on a list and see if we can get them calendared before the landmarks commission, and to move forward in a constructive and collaborative way. These are buildings and districts which I will honor as a member of the City Council.

Patrick Murphy: I am lucky enough to live in a historic district. And I thank God everyday that in 1965 we passed the landmarks act. It took the demise of Penn Station to do it. Someone said it took Penn Station to die so that others could live. And thank God we did that and we have it in New York. The character of this neighborhood is so wonderful because of it. People fought on the front lines and saved Grand Central and other things like that.

But this is a difficult issue. We’ve got to have a discussion citywide and get some objective criteria for what is good architecture. There are a lot of arguments about buildings that are representative of an era and that we need to keep them. But is that truly good architecture? I don’t know. I am throwing out the question.

Those are the kinds of conversations we haven’t had. The argument we are having is: “We want a hearing before the landmarks preservation commission now!” That is happening in this district. It is happening at 2 Columbus Circle. We really need to dialogue. I am a member of the Municipal Art Society, and I think that is a great place to begin this dialogue and come up with some objective criteria. What is modern architecture? What is good architecture?

It’s never going to be perfect, but we have to bring it back to that level. Emotions are flying. We have too much subjectivity. We are going to have an opportunity to landmark a lot of wonderful buildings here on the East Side and throughout the city.

Jak Jacob Karako: This is one of the insane questions. People think government is the answer for everything, for every problem, for every whim, for every wish -- it is not.

We are required to be an accountant to manage debt. We are required to be an artist and understand what is worthy art and what is not. We are required to be an architect to understand what is a good building and what is a bad building. We are required to be an educator to know which method is better to teach. We are required to be a zoning specialist to know how high a building should be.