VIDEO: 'We Were Forced To Watch Him Be Overmedicated'

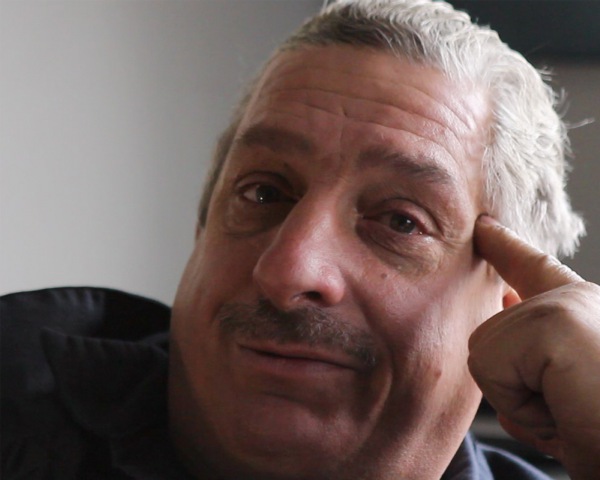

NEW YORK — For George LaRocca Jr., there was a striking difference between the man his father was before he was admitted to a nursing home and who he was afterward.

Before the nursing home, his father, a good-natured fix-it man, was so nimble it could be difficult to keep an eye on him. "You'd blink and he'd be gone and walk a mile no problem,” LaRocca’s son said. “He'd just be be-bopping down the road with his cane, but he'd always head home."

{sidebar id=9}

But after he was putting on antipsychotics at the nursing home, LaRocca Jr. said his father was transformed. Weeks after being admitted, he could barely walk.

This is the story of what happened to LaRocca's dad.

Investigation: How NYC Nursing Homes Drug Seniors Into Submission

NEW YORK — George LaRocca Jr. and his dad ran a Brooklyn auto shop together. Even when Alzheimer’s robbed the elder LaRocca of his memories and ability to work, his son brought him to work. But one day his dad wandered off and the younger LaRocca found him near some scrap yards. When LaRocca rolled up in his car, George Sr. said with a laugh, "I don't know your name but I know you belong to me."

LaRocca knew his dad needed more care than he or his mother could provide. So they made the difficult decision to admit him to Regeis Care Center, a nursing home in the Bronx with manicured lawns. Their motto: “The Road Back Home Begins with Regeis.”

{sidebar id=8 align=right}

Within a week at Regeis, his son says, his dad could no longer walk. Less than a year after being admitted on May 15, 2007, LaRocca was dead from a bloodstream infection brought on by severe bedsores. In testimony for a lawsuit brought by his family against the nursing home and later settled, Regeis’ own medical expert testified that antipsychotics given to LaRocca had “predisposed” the 78-year-old man’s skin to break down, which led to the bedsores.

Medical records show that soon after being admitted to the nursing home, staff began to administer two antipsychotic medications to LaRocca — even though he had no medical need for the drugs.

George LaRocca Jr., believes the antipsychotics killed his father. "They had him so drugged out he couldn't talk or eat,” LaRocca said.

For decades, researchers and regulators have known that nursing homes are prone to use antipsychotic drugs as a crutch to control patients. Research shows that the drugs — sometimes called “chemical restraints” because they can be the mental equivalent of strapping residents to wheelchairs and beds — can lead to falls, strokes, and even death. They are particularly dangerous for dementia patients. And regulators, while speaking out against the rampant practice, are failing to stop it.

An investigation into the use of antipsychotics at nursing homes in New York City shows the practice is widespread at facilities in the five boroughs — and loosely regulated. Among the findings:

{sidebar id=1 align=left}

• In New York City, about one-in-four nursing home residents – more than 9,400 people – were given antipsychotics in 2011, according to an analysis of the most recent data released by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. That’s out of a total of roughly 40,200 nursing home residents.

Antipsychotics are meant as a last resort, and are illegal if administered for the convenience of the staff. But the line is blurry because appropriate use is left to caregiver interpretation, so it is not always illegal. Abuse of residents with the drugs is difficult to prove, yet best practices mean they can often be avoided. Some nursing homes greatly reduce their dependence on the drugs to the point that almost none of their patients take them.

• An analysis of the CMS data also showed that one-in-three New York City nursing homes dose more than a third of their residents with antipsychotics. The loosely regulated use of antipsychotics is even more extreme in some of New York City’s 172 nursing homes.

At Riverdale Nursing Home in the Bronx, 59 percent of the 137 residents were given antipsychotics, including 16 percent of new residents, which is more than five times the national rate. Riverdale’s administrator, Mark Solomon, did not return calls for comment.

More than half of the 205 residents at Oxford Nursing Home in Brooklyn were administered the potent drugs. Oxford’s administrator, Norman Motechin, said he was not familiar with the numbers and declined to discuss them.

And, at the University Nursing Home in the Bronx, 49 percent of the 44 residents were taking antipsychotics, including 9 percent of new residents, which is more than three times the national average. Jennifer Capleton, the home’s director of nursing, claimed the data is wrong and said the facility was going through a state audit. She refused to elaborate. Medicare officials did not speak about the facility’s data specifically, but said the antipsychotic data is accurate.

• Analysis of Medicare data also shows that nursing homes with the highest rate of chemical restraints were associated with fewer nursing hours per patient, and higher rates of bedsores and depression.

• A review of inspection reports for the past three years for the 10 facilities in New York City that had the highest percentage of patients on antipsychotic drugs without medical justification revealed not a single citation for inappropriate use of the medications.

It’s impossible to tell from the Medicare data alone whether antipsychotic drugs are being abused by a nursing home. It’s possible that some of a nursing home’s patients, for instance, suffer from serious psychiatric disorders that would warrant the drugs.

When contacted for this story, however, the city’s nursing homes with the highest percentages of patients on antipsychotic drugs did not report significant populations of psychiatric patients.

The LaRocca family sued Regeis Care Center for negligence, because of the bedsores that led to his infection. There is no mention of antipsychotics in the case.

Regeis lawyer, Stephen Weiner, said the nursing home “followed the dictates of the doctors and psychiatrist management of the patient's medications, which were appropriate in his declining condition.” Weiner declined to discuss details of the case, and cited a confidentiality agreement related to the settlement, in which they admitted no guilt or liability.

Medicare contracts with individual states to license and inspect nursing homes. In New York, the state Department of Health is responsible for administering fines, or for shutting down repeat offenders (the city DOH has no oversight of nursing homes). Jackie Pappalardi, director of nursing homes at the NYSDOH, was asked to explain how publicly available Medicare data could show such a high rate of antipsychotic use, and yet the problem does not seem to show up in inspection reports by her agency. She would only say that her inspectors are trained to look for unnecessary drugs.

The Long Term Care Ombudsman Program also purports to protect the public, but shows no sign of addressing the problem of chemical restraints. The Ombudsman program, a partnership between the federal and state government, says it is “dedicated to protecting people” who live in nursing homes. In New York, the system cost taxpayers roughly $3 million in 2011.

Mark Miller, the New York state ombudsman, did not respond to multiple requests for comment over several months. Finally, he said through a spokesperson that “antipsychotics is outside their sphere of responsibility.”

Alice Bonner, director of the division of nursing homes for U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services CMS, says the regulatory process to fix the issue is slow, but in motion. In March 2012, under mounting public and political pressure, Medicare started a campaign to reduce antipsychotic drug use from a national average of 24 percent to 20 percent by the end of that year. Results of the campaign are expected next month.

“I know I’m not going to wake up and the problem will be gone,” Bonner said. “We're putting in the infrastructure to see the improvements over the next several months.”

“CHEMICAL STRAIGHT JACKETS”

As early as 1975, legislators were using the term “chemical straight jackets” to refer to the ongoing problem of drugging the elderly for convenience. Chemical restraints — defined as drugs used to control behavior or restrict movement that are not a treatment for the patient’s medical condition — were banned in the landmark 1987 Nursing Home Reform Act.

Dr. David S. Sherman, who studied geriatric pharmacology at Harvard University, was testifying before a Senate committee when he compared chemical restraints to the use of electroshock treatment as means to punish mentally ill patients. “I think that at some time in the not too distant future we will similarly look back at this time, the routine drugging of our elders, as an equally barbaric form of treatment,” he told the elected officials.

Sherman spoke those words in 1991.

The most common and unchecked chemical restraints are the 22 antipsychotics with names like Seroquel, Risperdal, Haldol, and Zyprexa. Decades of studies have concluded that these drugs can be lethal when used on seniors who do not suffer from a serious psychiatric diagnosis. In 2005 and 2008, the Food and Drug Administration issued “black box” warnings to physicians, saying antipsychotics increase the risk of strokes and death in people with dementia. {sidebar id=5}

A November 2012 study by Dr. Dilip Jeste, a geriatric psychiatrist at the University of California San Diego, showed that one-in-four patients given antipsychotics over the long term were rushed to emergency rooms for life-threatening conditions or died. One commonly prescribed drug had to be cut from the study because it was associated with twice as many severe health problems than even the other antipsychotics.

Experts and some nursing home employees say the drugs are being used to control patients, not to treat serious mental health problems.

Studies show serious mental health problems are rare at nursing homes. A 2005 study by Harvard Medical School showed only 2.3 percent of newly admitted nursing home residents have a serious psychotic diagnosis like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. And just 3 to 6 percent of long-term nursing home residents are diagnosed with schizophrenia or other serious mental disorders, according to a separate 2005 study by the Kaiser Commission. Only 1.1 percent of the U.S. population is diagnosed with schizophrenia, according to the National Institute for Mental Health. And yet an investigation by the Office of Inspector General in 2007 revealed that 88 percent of the Medicare claims for antipsychotics contradicted the FDA “black box” warning and were used for dementia.

BETTER CARE IS POSSIBLE, BUT ELUSIVE

If it’s well known that chemical restraints are dangerous, then why are they so common? The answer is ignorance, sometimes willful, on the part of the caregiving team, combined with a fragmented care system that makes it easy to rely on drugs to subdue patients.

Family members may unknowingly be part of the problem. Take the case of Abigail Dennis, who was struggling to take care of her mother, Anita Dennis, who has Alzheimer’s. The elder Dennis argued and screamed at her home health aide, so Abigail Dennis asked her doctor for help. He prescribed heavy doses of the antipsychotics Seroquel and Zyprexa. He gave no warnings.

“They turned my mom into a vegetable,” Dennis said of the drugs. “I had no idea about the risks, I just wanted her to be nice and not cause trouble for the aide.”

Dennis admitted her mom to Cobble Hill Nursing Home in Brooklyn, a facility that’s reduced its percentage of patients on antipsychotic drugs to 13 percent. Cobble Hill’s caregivers were shocked at the high dosages of the drugs, said Liza Long, head nurse of the dementia unit. They weaned the elder Dennis off them entirely. The nurses added that the elder Dennis went from kicking, biting, and screaming when she came off the drugs — to laughing and hugging everyone after proper care.

“I asked the staff what drugs they gave her and they said vitamins,” Dennis said.

Sufferers of dementia and Alzheimer’s are not just forgetful. In the later stages of these diseases, people can't express simple needs like hunger and pain. As a result, confused and frustrated, people lash out or behave in ways that are difficult to understand. Antipsychotics mute that behavior. But they’re not a safe solution, and less drastic measures are more effective.

Tony Lewis, the Cobble Hill administrator, described a resident who baffled staff when he regularly overturned tables at meals. It later turned out the large man was accustomed to being served his meal first in his Italian family. A dose of antipsychotics could have controlled the outbursts — but then again, so did bringing him his tray of food first.

Administrators like Lewis may be the nursing home insiders with the greatest influence on antipsychotic use. They set the standard of care, and the tone for caregivers. But Lewis said that without motivated administrators and caregivers, nursing homes settle for the status quo, which is geared for the use of chemical restraints.

Pharmacists who distribute the antipsychotics are spread thin – sometimes bouncing between four or more facilities across different boroughs. They can make recommendations about using such drugs, but have no authority over a nursing home’s medical staff.

Dr. Din Shah, who has been the pharmacist for 37 years at Providence Rest Nursing Home in the Bronx, said the facility's antipsychotic rate was at about 30 percent a decade ago. In 2002, a new medical director made lowering the dependence on the drugs a top priority. The rate dropped to 2 percent. That’s not the case at other nursing homes where Shah works, which have rates ranging up to 40 percent. He declined to comment about those facilities.

“I review the physician orders to make sure they comply with the regulations, but it’s a constant battle for behavior and for the safety of the resident and the other residents,” Shah said. “It has to be a team approach.”

Nursing home medical doctors often split their time among many facilities, overseeing hundreds of patients. Thus, they depend heavily on reports from nurses about patient health and may feel pressure to fulfill the requests of nurses who want help controlling patients.

Dr. G. Allen Power, a medical director at St. John’s Home in Rochester, said it’s difficult to respond to nurses who just want him to prescribe pills, and that antipsychotics are not the solution that they may seem. Power said nurses are often handed prescriptions for use on an "as needed basis" — which roughly translates to an open-ended license for nurses to administer such drugs. “In a lot of ways we’re creating excess disability,” Power said.

Rosanna Luna, the former director of nursing at The Buckingham at Norwood nursing home just west of Manhattan, said it’s not surprising that nurses often consider dosing patients with antipsychotics, because they often mistake the drugs as a safety measure, not a chemical restraint. Luna found a simple solution that dramatically reduced her nursing home’s rate of antipsychotic use. She forced her nurses to end their dependence on chemical restraints by requiring that they call Luna “day or night,” whenever they wanted to call the doctor for a prescription. She never got a call.

Medicare data show the use of antipsychotics at The Buckingham dropped to about 5 percent in 2010, a 66 percent reduction in a five-year period. Nursing homes too often lean on antipsychotic drugs to control behavior, Luna said.

“It’s easier to give residents a pill than sitting with them a few minutes to find out what’s bothering them and what’s causing them the distress,” Luna said.

LAX OVERSIGHT

Chaim Stern, the administrator at Bezalel Rehabilitation and Nursing Center in Queens, did not seem concerned that about half of his 117 residents were on antipsychotics in 2011. He refused to discuss the high rate of antipsychotic use. Instead, he pointed to Bezalel’s “five star” rating – the highest possible – on Medicare’s Nursing Home Compare website. Chaim said, “That's a whole picture of a facility."

But Medicare doesn’t include any metric to account for antipsychotic abuse in its rating system.

Regulators are sending mixed messages about the use of chemical restraints. They say they are most concerned about the safety of residents and that the use of antipsychotics must be reduced. But the oversight is toothless. Inspections that focus on the use of chemical restraints are virtually nonexistent. Penalties are rare, and some agencies intended to protect the public do not even concern themselves with the problem.

{sidebar id=6}

Modifying the data being reported by nursing homes is a big step in the process, said Alice Bonner of CMS, who worked 20 years as a nurse in nursing homes. Currently, Medicare requires nursing homes to report all “off label” use, which means the use of antipsychotic drugs in cases where patients do not have a psychiatric condition that warrants the use of such drugs. In addition, nursing homes must now report the percentage of new residents prescribed antipsychotics, which she said could signal inspectors earlier about problems.

Training inspectors has also been an important step, Bonner said, so they can identify when chemical restraints are being used and evaluate whether nursing homes have a process for weaning residents off the drugs.

Toby Edelman, senior policy attorney for the Center for Medicare Advocacy, says training is not enough. Even when inspectors flag these problems, the citations are weak. Nursing homes only need to respond to problems if inspectors mark violations as urgent. Nationwide, Edelman said, there were only four cases in the past six years of appeals by nursing homes for enforcement of antipsychotics used inappropriately. And the penalties were not severe. In one case, an Illinois nursing home accidentally killed a resident with an overdose of antipsychotics and was fined $4,400.

“Everyone should be outraged this is still happening. They have hearings about this every ten years,” Edelman said. “The standard has been around a long time and it just won’t happen without stiffer penalties.”

Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, an advocacy group in New York City, said there’s no excuse for the overprescribing. “They're professionals paid to provide care,” Mollot said. “They have no idea how to not give dangerous drugs that sedate them and might kill them?”

And he said the ombudsman’s office should be speaking out about the problem. They may not because they’re too cozy with the industry, he said. In New York City, the ombudsman's office is housed with the New York Foundation for Citizens, a provider of senior services and operator of adult care facilities. The foundation receives grants from the New York State Office for the Aging to fund the ombudsman.

Paula Goolcharan, director of New York City's ombudsman system, says the relationship does not compromise the integrity of their work. Goolcharan would not speak specifically about antipsychotics or the ombudsman program, which is overseen by the state, and refused to continue the interview after a few minutes on the phone.

Without regulators paying close attention to the use of chemical restraints, patients and their families have little recourse when harm occurs.

Attorneys do not focus on the issue. Suzanne Flanagan, the lawyer who represented the LaRocca family, has worked on nursing home cases in New York City since 2003 and said families often complain that their loved ones are "drugged up," but it’s hard to prove.

"By the time we get cases, we don't have a witness because most people are deceased." Flanagan said. "The family just tells us what they think happened and we have to piece this together."

George LaRocca Jr. still tears up when he looks at the empty chair in the auto shop office where his dad once sat. It reminds LaRocca of better days.

"You'd blink and he'd be gone and walk a mile no problem,” LaRocca said. “He'd just be be-bopping down the road with his cane, but he'd always head home."

____

Elbert Chu is a science and education journalist. He’s worked for The New York Times, Popular Science, Fast Company, and ESPN. His documentary photography has spanned Lubavitch Jews and Orphans in Nepal, to the devastation of Haiti’s earthquake and a school shooting. He and his wife live amazed by grace in New York City. www.elbertchu.com | @elbertchu

A Looming Public Health Crisis In Storm-Ravaged New York?

FAR ROCKAWAY, Queens — Weeks after floodwaters from Superstorm Sandy inundated his three-story home in Far Rockaway, Vern Clarke is pulling out the sheetrock and insulation from the walls of the first floor in a desperate bid to stop the spread of mold throughout the structure.

"I can't wait for anybody to do it," said the father of five. "The longer you wait, the worse the situation becomes."

Public health experts, volunteers and residents are sounding the alarm about mold that is rapidly growing in homes that were flooded by Sandy, saying it could pose a potential health hazard for families who have nowhere else to go.

And experts say the problem could get much worse as colder winter weather closes in and power is restored to more homes that haven't been fully dried out.

Jack Caravanos, a professor of environmental health at the City University of New York who has been visiting homes in the Rockaways to evaluate the problem, said the combination of heat and moisture are ideal conditions for a mold explosion.

"If the area is not completely dried out, mold will take off," he said. "And here's what's interesting with mold — it can cause asthma … It can exacerbate asthma … Being exposed to mold can make it worse and trigger an attack."

Greater NYC for Change, a 6,000-member activist organization that sprung from the 2008 Obama campaign, has started a petition on Change.org calling on government officials to deploy temporary housing — possibly including FEMA trailers or Red Horse Squadron tents — to help people get out of their flood-damaged, mold-infested homes. The petition has over 11,000 signatures.

There are currently few housing alternatives for those whose homes were damaged in the storm — the hotel vouchers provided by the city put Rockaways residents far away from their jobs, leaving them with an untenable commute, and shelters can be difficult environments for families.

Advocates said they are increasingly frustrated by what they see as willful apathy toward the problem of mold and the lack of housing alternatives.

Ret. Army Col. John Hoffman, who has been advising a number of emergency response groups in the Rockaways, said temporary housing would alleviate a number of problems.

“We are having issues distributing hot meals and getting medical care to people. Temporary housing would fix that, it would stabilize the community while homes are being rebuilt," he said. "In a lot of cases, the mold is not going to go away overnight. People will need places to live … These requests for temporary housing have fallen on deaf ears.”

State Sen. Joseph Addabbo, whose district includes the Rockaways, said FEMA and city officials are considering a plan to lease empty apartments to house residents who are either displaced or living in unsafe conditions due to the storm.

“Thirteen thousand residents in the Rockaways are without power,” Addabbo said on Friday. “There is no question the goal is to find temporary housing.”

He said FEMA trailers "aren't ideal" and that the federal agency has been trying to balance "cost and safety." “They are finding that area hotels are booked or have tripled rates," he said. "But there are hundreds of empty apartments in the Rockaways that FEMA is looking at.”

Clarke said FEMA sent someone to check out the damage to his home, but that his family was not offered housing assistance. "Well, the gentleman came in to do the interview," Clarke said. "There was mold already on the baseboard. He said, yeah, this is no place for the family and kids to be ... But we got denied for help."

The alternative — a hotel room — was also proving impossible to find. "There's no place," he said. "There's no place that could set up a family of seven."

Representatives of FEMA didn't return calls last week requesting comment on the situation facing families living in mold-infested homes.

A CREEPING PUBLIC HEALTH CRISIS?

In the days after the storm, St. Francis de Sales Parish, in the Belle Harbor neighborhood of the Rockaways, has become a refuge for storm weary residents.

In the lot across the street from the church, only a couple blocks from the beach where some houses were shredded and others were thrown off their foundations, tents have been set up to provide emergency assistance. During a recent visit to a heated tent where free hot meals were being served, dozens of dusty laborers, some with masks propped on their heads to eat, were gathered alongside residents.

Dennis Saleeby, volunteer field operations director for New York Resilience System, said he has seen people developing coughs and becoming ill and points to mold and other contaminants. “The particulates, the mold and asbestos are creating a toxic environment,” he said.

Saleeby and a number of other regular volunteers were shocked by recent comments made by the city's assistant health commissioner, Nancy Clark, to WABC-TV.

"We are monitoring emergency room visits and hospitalizations for illnesses, respiratory illnesses and to date we've not seen an up-tick but we continue to monitor," Clark said in the interview.

Saleeby said people who are living in conditions surrounded by mold aren’t likely to go to an emergency room.

“That is a very reactionary response to a health crisis," he said. "How many people in the Rockaways see private doctors, go to clinics or are too poor to go to the emergency room?”

Perhaps in a nod to the growing concern, the city’s Department of Health sent two staff members on a fact-finding trip to the Rockaways, a spokeswoman for the department confirmed. She would not provide details. Caravanos, who was with the team, said that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration also sent someone along on the trip Thursday.

Caravanos said it was difficult to pinpoint one health problem as being caused by mold. "Some people have irritation, upper respiratory respiration, cough, headaches, malaise … A mixed bag of symptoms that may or may not be mold specific but can be," he said.

The good news, he said, is that so far what he and others have seen amounts to "pretty much ambient mold" — such as penicillin and aspergillus — that can affect people who are susceptible, such as those with asthma and allergies.

But he said that more toxigenic molds, such as stachybotrys, could be looming on the horizon if homes are not dehumidified properly — and that could be more problematic. "Those molds will cause disease in just about anyone exposed," he said.

A growing body of literature exists on the health effects of mold, especially among vulnerable populations, including children and those people more susceptible to respiratory illnesses.

A 2004 study from the Institute of Medicine found that epidemiological studies "indicate there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the presence of mold … indoors is associated with upper respiratory symptoms, cough, wheeze, asthma symptoms in sensitized asthmatic persons…"

The association between mold and upper respiratory symptoms was a focus of concern in post-Katrina New Orleans, where the subject has been studied extensively.

And, as in New Orleans, activists and public health experts like Caravanos are moving aggressively to try to educate about the potential hazard of mold and the need to dehumidify buildings.

Alison Thompson, another volunteer coordinator and a longtime disaster responder who has been working out of a trailer on the St. Frances lot, said lessons from Katrina and from the toxic dust at the World Trade Center should be applied in the Rockaways.

“They’re saying it’s totally fine out here. It’s hard to believe that,” she said, adding that she had been visiting homes and finding a host of people complaining of respiratory problem.

One group that formed to respond to the problems caused by the storm, Respond and Rebuild, had planned to hold two mold clean-up community presentations in the Rockaways and Coney Island.

Caravanos was among the speakers, along with Guillermo Olivos, described in a flier as a “leader of mold remediation for recovery groups” following Hurricane Katrina, and Jolanta Kruszelnicka, described as an industrial hygienist on her LinkedIn page and as an adjunct professor at the Long Island University School of Public Health.

RESTORING HEAT, POWER; IGNORING MOLD?

In recent days, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has been touting the city's Rapid Repair program, set up by his office, to provide free emergency repairs to help residential property owners affecting by the storm to restore heat, water and electricity.

"NYC Rapid Repairs teams will visit any storm-damaged house that is structurally sound, provide a free assessment of what needs to be done to get basic services restored, and then do the work for free," he said in his weekly address on Nov. 25.

But the program doesn't deal with mold. “They are taking out sheetrock and other flood damaged material, but they are not in the mold removal business," Addabbo said.

Caravanos said he and other public health experts were trying to change that. "They are leaving you with a moist house ready to ferment," he said of the Rapid Repairs program.

The mayor's office didn't respond to an emailed request for comment about mold remediation efforts and the Rapid Repair program.

But without city or federal help, landlords and homeowners are left to deal with the mold problem themselves. But often landlords aren’t equipped to deal with mold damage and, in some cases, the damage is so extensive residents shouldn’t expect to be back in livable apartments anytime soon.

There are also plenty of people out there looking to make a quick buck and ready to pose as mold remediation experts — a possibility made easier by the fact that there is no state licensing requirements for anyone to say they are.

In the immediate impact of Hurricane Sandy, Brandon D’Leo and the surf club he works out of in Queens had a distinct purpose: help as many people as possible.

“We got together and just sent people through the neighborhood to canvas and find out what people needed," he said. “We sent out crews of volunteers to dig people out and do demolition.”

Now D’Leo says “things have really changed” — but not for the better. Thanks to long festering mold in houses that have been without heat for weeks, it isn’t as simple as sending volunteers out to tear out a water-soaked interior. “At about three-and-a-half weeks in, we couldn’t send people into those conditions any more because of the mold," he said. "It is just irresponsible."

D’Leo said he is acting more as an intermediary — sending volunteers to organizations that are properly outfitted to handle toxic mold.

Clarke, the resident who had stripped his first floor to deal with the mold, said it had been two weeks since a crew from the Rapid Repair program had come by.

In the meantime, as he awaits their return, he said he is going to have to pull out the kitchen cabinets and the stove and keep working toward fixing up his house so that his family can get back a sense of normalcy.

"Everybody is just trying to hang in there," Clarke said. “It's not a comfortable situation. It's not a happy situation. it's just a situation where you're making things work day by day."

Fear and Cowering on Paid Sick Leave; Advocates Dodge Right to Discharge Bill over Speaker's Objections

Photograph of paid sick leave rally by William Alatriste.

NEW YORK — In the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Democrat Tom Cuite was at the helm of the City Council, he made sure the city's landmark gay rights bill was killed in committee nearly a dozen times.

I was involved in the 50-group, all-volunteer Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights at the time, and we demanded the sponsors of the Council bill force a vote on it, even if the bill might lose, to get them on the record.

When the speaker of the City Council refuses to schedule a vote on a bill, the lead sponsor has the right to file what is known as a discharge motion with seven others to bring it to the Council floor for a full vote by their colleagues.

But it might as well be the nuclear option, because most sponsors and advocates run for the fallout shelters when asked about whether they would consider standing up to the leadership.

“Cuite punished members who defied him by going so far as to withhold mail from them, but the ones who stood with us believed civil rights were more important than personal perks,” said Allen Roskoff, who worked on the gay rights bill since it was the first in the nation to be introduced in 1971 at the behest of the Gay Activists Alliance.

No discharge motion is known to have passed the Council, with some members in past Councils claiming that even though they supported the legislation they were voting no because they opposed bypassing the committee system.

The gay bill finally passed in 1986 when Peter Vallone, Sr., became majority leader and let it go to the floor despite his personal opposition to it in a deal he made with Council Member Robert Dryfoos, a supporter of the bill, who betrayed the Manhattan delegation to vote for Vallone as leader over Sam Horwitz, forever earning Dryfoos the nickname “Benedict Bob.”

Today, it is difficult to see how such a coalition of activists and Council members might come together to force a vote on the bill that would require some employers to grant sick leave to employees with Speaker Christine Quinn implacably opposed to the legislation. After all, this Council has never used a discharge motion under her tenure.

How Can a Bill with 36 Sponsors Not Come to a Vote?

The sick-leave bill (Intro 97-A) has a more than veto-proof majority of 36 City Council co-sponsors – just 34 are needed for a two-thirds override of the mayor’s promised veto of the bill. But the legislation has languished without a vote because of the opposition of one member, Quinn, and the refusal of her members to contradict her. She shelved the bill in 2010, telling the New York Times it “threatens the survival of small-business owners.” The 36 sponsors didn’t say boo to her blocking the bill and, while some of the advocates wailed at the time, none demanded a discharge motion.

While Quinn does not have the legal power to stop a bill from coming to the floor, her fellow Council members have been astoundingly silent — or evasive — when it comes to discussions about asserting their right to bring a discharge motion.

I asked a few Council members at an August 22 religious rally for the sick paid leave bill on the steps of City Hall why they weren’t using the power of discharge.

Councilman Robert Jackson dodged the question. “It’s not my bill,” he said, though he is a sponsor. He added that it “hasn’t come up” in their strategy meetings to get the bill passed.

Would there be consequences for him if he did support a discharge motion? “I don’t know,” he said.

Councilman Jumaane D. Williams (D-Brooklyn), considered one of the more independent members of the Council, said, “I don’t have an answer. It’s a good question. But nobody’s asked us for that.”

Councilman James Sanders, Jr. (D-Queens), who chairs the economic development committee in which the bill has been heard and stalled, said he could not give me a “good reason” why there has been no committee vote and that any request for discharge would have to come “from the prime sponsor,” Councilwoman Gale Brewer.

At the same rally, Brewer would not answer questions about whether she would consider using her power to bring a discharge motion.

“I’m going to work with the leadership to get a bill,” she said, though would not say whether the bill would change before it goes to a full Council. “We are going to get a bill,” she emphasized.

Critics fear that as Council members negotiate the bill, it will be tempered, much in the same way that living wage legislation was made more palatable for the business sector before it was allowed by Quinn to come to the floor.

Roskoff, a longtime critic of Quinn’s leadership and closeness to Mayor Bloomberg, issued a statement on behalf of the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club, where he is president, demanding that Brewer bring a discharge motion on the bill or for supporters of the bill to select a new lead sponsor who will.

“If Council members are not willing to stand up to the speaker for what they allegedly believe in, we might as well dispense with having a City Council entirely and save the city a lot of money,” he wrote in an August 27 statement.

Where Are The Advocates?

Most advocates for the bill would not answer direct questions about whether the option of demanding a discharge motion has even been discussed.

“At this point, we have not viewed it as a viable mechanism. That’s what I’m saying in August. It may not be our position in two months,” said Martha Baker, a leader of the New York State Paid Family Leave Coalition.

Instead, Baker said they were “trying very hard” to work with Quinn.

“She has the power to bring the bill to the floor. History tells us that discharge is not usually the most effective way,” Baker continued.

Groups such as the Working Families Party and the Community Service Society have been bombarding their members with pleas to call on Quinn to schedule a vote, but in the face of her continued resistance to the legislation they are not demanding that Council members bring the bill to the floor themselves through discharge.

“It is time for Speaker Quinn to heed the calls coming from all directions, and bring paid sick days legislation to the floor for a vote,” said David Jones, president of the Community Service Society in a release, but his group would not provide their stance on a discharge motion.

Working Families also would not answer the question on discharge, emailing this statement: “The proposal has been crafted in consultation with small business owners, and we're asking Speaker Quinn to allow a vote on the City Council floor. Speaker Quinn has a long history as an advocate for working people and as a supporter of public health, and we're optimistic that we'll get a vote on the floor, with her support.”

While Quinn’s office said that no discharge motion has been brought during her tenure, Councilman Charles Barron (D-Brooklyn) said he was part of a group that gathered the signatures from sponsors to bring a discharge motion on a bill relating to voting machines and the speaker’s office responded by releasing the bill from committee.

Barron seems to be alone among Council members in his willingness to take Quinn on over her leadership; he said he has paid for it by being removed as chair of the council committee on higher education.

“There is no democracy in the City Council,” he said. “It is the dictatorship of the Speaker” — something he knows something about as the man who hosted a Council reception for Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe, though Barron regards him as a “liberator” — which indeed he once was.

“Members are afraid to assert their own power,” Barron said of his colleagues. “They fear the speaker who they give too much power. Nothing in our rules says that she controls capital money and expense money, but they let her determine how much we get. Funds are not distributed based on the need of impoverished communities. They go to the Council members who go along, get along, and do the speaker’s bidding. She determines what committee assignments we get and whether we get to chair a committee.” He said he has his own way of bringing resources to his district by negotiating directly with city agencies.

Of the advocates who are not demanding discharge, Barron said: “All of them are afraid to confront the speaker because they have other deals in the pipeline.”

Barron wishes his colleagues would stick together on issues that are supposed to be their highest concerns, particularly matters of economic justice. “She can’t punish all of us. If the majority of us said no to her, we win.” He “guarantees” the sick-leave bill “will be watered down the way the living wage bill was.”

Indeed, despite the fact that the bill as written has 36 co-sponsors, Brewer has announced that she is negotiating changes in it. In her latest email newsletter, she wrote: “We are working to address the concerns of business owners who have legitimate concerns about the language in this bill.”

Mayoral politics are a factor here. “It is obvious to us that from what I read, there are powerful interests in the city who would support the speaker for mayor and don’t support this bill,” Baker said. “That has to have an effect. Other folks who are running for mayor — de Blasio, Stringer, Liu, Thompson — everybody appears to be in support except the speaker”

Several Council sponsors of the bill who I have often gotten comments for my stories in the past would not respond to calls for comment on the question of bringing a discharge motion — including Daniel Dromm (D-Jackson Heights), Rosie Mendez (D-Lower East Side) and Daniel Gorodnick (D-East Side). None of them returned calls or emails.

When I reached out to Quinn’s office, I received no response to the charges of her critics.

While the New York Post and New York Daily News editorialize that Quinn should hold firm in stopping the bill, The New York Times wrote that Brewer and Quinn “should be able to find a workable compromise” on the bill that they say Quinn supports “in principle.” The fact that 36 sponsors will not bring the bill up for a vote on their own raises not just the question of their independence as representatives, but whether they were just putting their name on a bill that they do not truly support and were counting on Quinn to kill or amend.

“It is time for all City Council members to stand up for what they say they believe in and pass this bill intact. A discharge motion is rarely used in the Council, but it is the only hope the bill has of passage in its current strong form,” Roskoff said.

___

Andy Humm is the co-host of the weekly Gay USA cable TV show, a contributor to Gay City News, and a former city Human Rights commissioner.

The Public Health Case for Paid Sick Days

Photo (cc) The Suss-Man

NEW YORK — Many who oppose requiring businesses to give paid sick days to workers — among them Speaker Christine Quinn, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and industry groups — have been arguing that to do so in today's enfeebled economy would be too much to ask of employers.

But there is a public health case for paid sick leave that has gotten much less attention, and has been bolstered by recent studies.

Nancy Rankin, a researcher with the nonprofit Community Service Society, said there is a good reason opponents of the bill are focusing on economic arguments.

"The opposition realizes they can't win on the public health issue. It's so obvious that it has merits … They are not even fighting on it," she said.

In recent months, advocates have been campaigning for a City Council bill that they say would give tens of thousands of mostly low-wage workers paid sick days off.

Originally introduced by Councilwoman Gale Brewer in 2009, Quinn shelved the bill a few months later, citing the torpid economy at the time. Now it is back in a much modified form, but Quinn has continued to refuse to bring it to a vote on much the same grounds.

“With the current state of the economy and so many businesses struggling to stay alive, I do not believe it would be wise to implement this policy, in this way, at this time," she said in a statement in response to a letter urging a vote on the bill that was signed by feminist author Gloria Steinem and about 200 other influential political, labor and public health leaders.

According to the Bureau of Labor statistics, as of 2010, 61 percent of workers in the private sector had paid sick leave, while 89 percent of state and local government workers did as well.

There is currently no federal law that requires companies to provide paid sick leave, and workers at companies with 50 or more employees can get 12 weeks of unpaid leave under the Federal Family and Medical Leave Act.

The Healthy Families Act, introduced into the House of Representatives, would set a "national standard" for paid sick days.

Meanwhile, advocates at the local level have successfully pushed laws to pick up the slack, including in San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

The problem of workers going to their jobs while sick was highlighted during the 2009 outbreak of H1N1, also known as as the swine flu.

In a study published in the American Journal of Public Health in January, researchers sought to find out if such factors as the inability to take time off from work, the need to take public transportation and crowded households made people more likely to contract H1N1.

The study was based on a sample survey of over 2,000 adults through in early 2010. Responses were sought on questions including: "If public health officials declared that it was necessary for people to stay home from work and school, how difficult would it be for you to stay home from work for 7-10 days?"

The conclusions of the researchers might not be so surprising — finding that social factors did indeed contribute to a higher number of people getting sick from flu-like symptoms during the 2009 pandemic.

Especially affected were Hispanics, who were not only found to be at greater risk of exposure because of social factors but also to be unable to get medical help.

"These facts have implications for policies: there is a need to provide better access to vaccines, drugs, and culturally competent health care providers," the authors of the study wrote.

A separate study by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control that was published in July found that workers without sick leave were more likely to skip going to a doctor for preventive screenings, such as mammograms, Pap tests or endoscopies. The study was based on data from the 2008 National Health Interview survey.

Whether a person obtained preventive care was determined largely by the jobs they do, the authors said, writing:

A person’s occupation is the source of some of the most critical elements determining their health and well-being. And in the United States, access to these benefits is largely determined by the type of occupation. The percentage of workers with access to paid sick leave is lowest among service workers, workers in construction and maintenance, transportation workers, and part-time workers, and highest among managers and professional workers. This occupational structure disproportionately affects women who are more likely to be low-wage and part-time workers."

In a third study published this year, workers who had paid sick leave were found to be "28 percent less likely overall to suffer nonfatal occupational injuries."

In a post on the CDC's blog, the authors of the study wrote that they had concluded that "access to paid sick leave might reduce the pressure to work while sick out of fear of losing income."

Rankin and other advocates see it as a sign of hypocrisy that the mayor is seen as a pioneer of innovative public health policies but is against paid sick leave, given the research to support it.

"It's a good time to do it," Rankin said. "It's a time when workers are hurting, and so they are really worried about hanging on to their jobs, and that forces them to come into work sick. And it's something that would help workers."

The city's Department of Health, which is the Bloomberg administration's chief cheerleader of policies including the ban on trans-fats and the proposed regulation to limit the size of soda containers, declined to comment for this story.

In a roundtable discussion organized by CSS in April, some business leaders have agreed that it is better if workers avoid going to their jobs while sick, but were opposed to the Council's bill.

"People should never ever have to fear getting fired or getting punished for calling in sick. And we, like the rest of you, do not want to see any employee going to work when they’re ill. It’s just a question of how we get there," said Jack Friedman, representing the Five Borough Chamber Alliance.

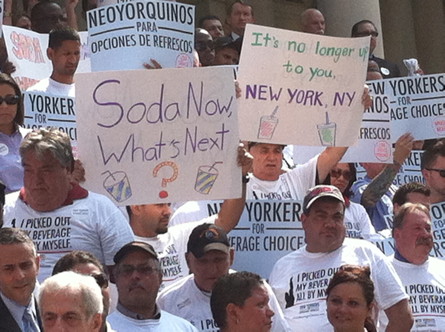

Beverage Industry Fight Against Soda Ban Just Beginning

Photo of man testifying at Board of Health hearing by Nina Goldman.

NEW YORK -- The trendsetting public health initiatives that Mayor Michael Bloomberg has successfully pushed -- smoking bans in restaurants, bars and public places, as well as health inspection ratings -- have been picked up across the country by dozens of other cities.

If beverage makers and retailers have their way, the Bloomberg administration's next big idea to limit the size of sugary drinks sold to no more than 16 ounces won't have that much fizz. What's at stake for them is not merely consumer choice but the possibility that the soda ban will start a trend that will sweep through the country.

"The New York City battle is the industry’s finger in the dyke,” said George Hacker, senior policy advisor for the Center for Public Science in the Public Interest.

Yesterday, the mayor-appointed Board of Health, which will make the decision on whether to pass the regulation, held its only public hearing on the proposal that would apply to any outlet that requires a health inspection by the city.

About 60 people spoke at the hearing held at the Department of Health in Long Island City, Queens. Eight out of 11 board members were present.

As was expected, several health experts and representatives of community organizations testified that soda is playing a large role in the obesity epidemic in America.

Several elected officials, including Council members, expressed their indignation about the decision to pass the far-reaching legislation to an unelected administrative body.

Beverage industry supporters said the plan would strip them of their freedom to choose.

Before the hearing began, Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said the proposal was "at its core" about the health of New Yorkers.

He sid if a virus was killing as many New Yorkers this year as are killed by obesity every year, people would be clamoring for government intervention. "Sugary drinks are the leading cause of the obesity epidemic in New York City,” he said.

Farley said that the limit is not restricting anyone’s rights because it still allows New Yorkers to drink as much as they want – it just limits the sizes available to them.

He said the initiative would be enforced during health department inspections and violators would face a $200 fine.

During the hearing, New Yorkers for Beverage Choice, which sprung up in response to the proposed regulation, said it delivered comments opposing the ban from 91,000 New Yorkers and 1,500 businesses.

Hacker said the industry is likely to pursue a number of avenues in their battle against Bloomberg’s policy – a public relations campaign, swaying members of the Board of Health, legislation on the state level and litigation.

In the end, the industry might not have much choice. "They may just learn to live with the new rule and hope that it doesn't seep outside of New York City," he said.

The Legal Battle

If the Board of Health goes ahead with the ban when it votes in September, it will almost certainly face a lawsuit before it goes into affect in 2013.

Farley was asked about a possible suit at the hearing and responded: “I would hope the industry wouldn’t do that. I think that simply hurts the reputation of the industry.”

Industry experts say that although it is likely many lawsuits will be filed against the ban, it isn’t clear that any particular argument will hold up in court.

Some possible challenges could include claiming the ban is "inequitable" -- as Council members Dan Halloran and Letitia James have argued. “This is going to set up an unfair competitive advantage,” James told the Gazette.

Farley argued at the hearing that the industry wouldn’t face any drastic cost increases, because the move from 20 ounces to 16 ounces is a small one and that small restaurants and eateries don’t generally serve drinks over 16 ounces.

Another argument could be that the ban violates the Constitution’s Commerce Clause that prohibits states from taking action that can hurt interstate commerce. Large soda producers could claim they are hurt by the ban.

The city's Law Department said the Board of Health was well within its authority to set the new regulation.

"The Board of Health is charged with regulating all matters that affect health. Specifically, its areas of oversight include the control of chronic disease and food service establishments,” said Chief Legal Counsel Stephen Louis. “Limiting the portion size of sugary beverages served at NYC restaurants is a valid exercise of these authorities."

The administration successfully defended challenges to its policy that banned smoking in bars and that required chain restaurants to post calorie counts in their menus. However, the administration recently lost a legal battle over graphic signs designed to show the health effects of smoking.

Michelle Simon, a public health lawyer who runs the blog “Appetite for Profit," said in the short term the beverage industry is relying heavily on public relations.

“I think the broader strategy is to send a message to other cities: "Don’t even think about this or you will be next target of ridicule," she said.

She said other cities are likely to wait and see what happens with the lawsuits against the soda ban before they more forward with similar plans, just as they did with the calorie labeling initiative that Bloomberg helped pioneer.

"Not many other mayors have the luxury of not worrying about their popularity," she said.

A Legislative Solution

City Council members, including Halloran, are consulting with members of the state Legislature for ways to override the measure.

Attacking the issue on the state level could give the American Beverage Association a shot to do what the beverage industry has so far failed to do on the city level, where it has poured a small fortune into advertising campaigns to motivate city residents to voice their opposition to the ban.

The ABA, however, has had success pouring on the lobbying dollars and influencing policy in Albany. The ABA spent $12.9 million in 2010 to successfully defeat then-Gov. David Paterson’s proposed tax on sugary beverages.

State elected officials have been cautious about taking up the cause of the beverage industry.

“We may be getting to close to Big Brother,” Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver was quoted as saying in the New York Post in June, but he quickly walked back the statement saying addressing Bloomberg’s soda ban was not a priority for the Legislature.

When Gov. Andrew Cuomo was asked about it in June on a radio show, he noted a basic support for fighting the obesity epidemic.

When asked if he would veto any attempts by the Legislature to undo the ban Cuomo said there wasn’t much point in interfering because Bloomberg’s successor will be able to review the initiative. “Then, if people really object to it, the next mayor can just undo it. I don’t think you can do a lot of harm in the interim.”

The Soda Ban and the Power of the Board of Health

Examination of diseased cattle by the members of the Board of Health, 1868.

NEW YORK – In September 2006, the city’s Board of Health announced it was weighing whether to require chain restaurants to post calorie information on their menus.

The goal of the regulation, the city’s Department of Health argued, was to address obesity – at the time more than half of adult New Yorkers were said to be overweight or obese.

The industry mobilized to stop the plan. Weeks of debate and a public hearing followed. Mayor Michael Bloomberg loudly championed the proposal and, in December, the Board voted unanimously to amend the health code with the new regulation, spurring the restaurant industry to unsuccessfully sue to stop it.

Ë™

Tomorrow, the Board of Health will hear from the public on another contentious proposal aimed at tackling the obesity crisis -- a ban on the sale of soda sizes larger than 16 ounces at restaurants, mobile carts, delis, movie theaters, arenas and stadiums or any other venue that receives a city health inspection. The proposal has stirred up the hostility of the beverage industry.

Critics and other observers say they expect the script to largely follow previous efforts to pass new regulations, with the final decision up to the Board’s group of 11 physicians, public health experts and scientists, including the health commissioner _ all appointed by the mayor.

James Colgrove, a public health historian and the author of “Epidemic City: The Politics of Public Health in New York,” said that since its beginning the Board has had “very sweeping powers” – but that it had grown increasingly influential under the Bloomberg administration.

“Bloomberg has made public health a centerpiece of his mayoral administration in a way that no other mayor has,” he said.

Some elected officials – including City Council members – and business leaders have criticized the Board's increasing importance.

City Councilman Daniel Halloran, a Republican, said the soda ban regulation was “going to be done strictly by fiat.” He added: “Any time we are going to regulate like this, I think it’s something that the elected officials need to vote on.”

At a rally to oppose the soda ban at City Hall today, he said: "The agency's already made up its mind. Having the hearing is pointless."

A business and industry-backed group that sprung up in response to the proposal and has waged a campaign to stop it agreed that the Board would be unlikely to oppose the mayor.

“We believe that there should be a vote of the City Council. It represents the citizens of the city,” said Eliot Hoff, spokesman for New York for Beverage Choices. “The Board of Health answers to Mayor Bloomberg.”

The mayor’s office said the Board was the appropriate venue for the proposal.

“The Board of Health was designed to make public health decisions based on science, not political pressure, and that's just what it will do,” said Samantha Levine, a spokeswoman for the mayor’s office.

ATTACKING OBESITY

According to the Department of Health, more than half of New Yorkers continue to be overweight or obese – in spite of efforts by the city to encourage healthier eating and lifestyles.

Among the many indicators that obesity has reached a crisis point in the city include data showing diabetes has increased 16 percent between 2002 and 2010 and that about 5,800 deaths are linked to complications from it.

Obesity also disproportionately affects low-income and minority communities – and it is costly, with about $2.7 billion spent in Medicaid expenses in 2006.

The proposal for a soda ban came out of discussions of a task force convened in January by the mayor’s office to aggressively address obesity that involved the commissioners of 11 city agencies.

The task force announced 26 recommendations in May, including the installation of 700 new water jets and salad bars in schools; a push to create new urban agricultural sites; encouraging markets to publicize healthier alternatives to junk foods; and evaluating all city construction projects for opportunities to design buildings to encourage an active lifestyle.

But it was the proposal to establish a maximum size of sugary drinks that galvanized the attention of the beverage industry and commentators across the country.

If passed, it would apply to non-alcoholic, sweetened beverages that have more than 25 calories per 8 fluid ounces and less than 50 percent milk.

On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart joked that the proposal “combines the draconian government overreach people love with the probable lack of results they expect!" In contrast, filmmaker Spike Lee said he was in favor of it, calling obesity “a major, major problem in this country.”

The beverage industry raised the specter of overregulation – and even ran a full-page ad in newspapers of Bloomberg dressed as a nanny.

A group of 14 council members wrote a letter to the mayor on June 1 announcing their opposition. It was clear almost immediately that the Bloomberg administration would bypass the City Council and go to the Board of Health to get the ban passed.

“Many responsible, healthy, New Yorkers choose to consume soda in moderate amounts on certain occasions such as at a movie or baseball game,” the letter read. “Drinking a 20 ounce bottled soda with lunch is standard practice for many New Yorkers and does not necessarily reflect an unhealthy lifestyle.”

Councilman G. Oliver Koppell, who was among those who signed the letter, said that when a public health matter was complex and required specialized medical knowledge, it was understandable that the Board of Health would make a decision about it.

But he said that, in this case, the Council should have had some say in the matter.

“It's a decision about how far government should go in regulating people's lives,” he said. “I think it is appropriate … for a legislative body representing the people’s view to be heard.”

At a June 12 hearing, the Board of Health largely proclaimed its support for the proposal – although there were questions and some objections raised by the members.

“I just want to second the concerns about excluding juice, even 100 percent juice, and milk-containing beverages,” said Dr. Joel Forman. He said those drinks “have monstrous amounts of calories in them.”

Dr. Sixto R. Caro, another board member, said he was concerned that smaller businesses in lower-income neighborhoods would be unfairly burdened by the proposal.

In the end, the board voted unanimously to hold its only public hearing on the matter and to take comments.

Hoff, the spokesman for New York for Beverage Choices, criticized the timing and place of the meeting , saying that 1 p.m. on a Tuesday was problematic for businesses that attract a lot of customers during that time.

“It’s in the middle of the day in Long Island, Queens,” he said. “It’s not convenient for different parts of the city.”

He said hearings should instead be held in all five boroughs.

However, comments on the proposal can be made online as well.

FROM YELLOW FEVER TO OBESITY

The first Board of Health was formed in 1805, in response to Yellow Fever that had killed thousands in nearby Philadelphia. The Department of Health was created in 1870, with the Board overseeing the new division of government and the city’s powerful health code.

From the 19th to the 20th centuries, the Health Department focused most significantly on addressing infectious and chronic diseases.

The city’s health officials won pioneering battles to decrease child mortality rates, implement lead poisoning testing for children and battle AIDS.

Meanwhile, the Board’s almost unhindered oversight of the health code remained in place.

Colgrove, the public health historian, said the current focus of the Board and the Department on obesity and other so-called lifestyle diseases was appropriate.

“They are continuing the tradition that they've had all along: It's their job to protect people from what makes them sick,” he said.

Over the past few decades, the Board had on occasion become a locus of controversy – for instance, in the 1990s, a health code change allowed the Department of Health to detain those infected with tuberculosis to be detained as a last resort for treatment.

But it was not until Bloomberg came into office in 2002 that the authority of the Department of Health and, in turn, the Board, was used so assiduously – and some would say brazenly – to pass public health measures.

These have included smoking bans in restaurants, bars and, last year, parks and beaches; a ban on trans-fats in restaurants; and, of course, the posting of caloric information on menus.

The Bloomberg administration has not always gone straight to the Board, however, to change the health code, instead seeking out the support of elected officials.

But while the City Council could, in theory, pass some of the same regulations to protect the public health, it might behoove the mayor and health officials to stick to the Board.

“Strategically, you might say it is in the city's interest to do it through the health code because it is easier,” Colgrove said.

____

Nina Goldman contributed to this report.

Bronx senator's health quest

Photo ©iStockphoto.com/Ekaterina79

Visitors to state Sen. Gustavo Rivera’s Facebook page have become accustomed to seeing updates about the number of steps the Bronx politician has taken on a particular day.

On Dec. 9, 2011, for instance, he posted an update notifying friends that he had taken 698 steps over 11 minutes at 11:35 a.m. And, on Dec. 27, 2011, he walked 9,456 steps over 125 minutes at 9:40 a.m.

The 6-foot-2 Rivera, who is now down to 270 pounds from a high of 299, wasn’t always so worried about his weight.

But just after his election in 2010 in which he beat recently convicted former state Sen. Pedro Espada Jr., the Robert Wood Johnson foundation released a study that found that Bronx County was the unhealthiest in the state for the second year in a row. Not only was the Bronx the state leader in smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, excessive drinking, teen birth rates and even STD infections -- it also had a higher average number of premature deaths per 100,000 people.

Rivera decided he better start setting a better example by getting more exercise and eating better, all the while documenting his quest to slim down in the public eye.

“It was hard at first,” Rivera said. “But if it takes some fat guy to get up there and tell you his weight to get people thinking about the little changes they could make in their life then it’s worth it.”

It’s not just a personal quest to get healthier. He has also made improving health in his district and the state cornerstones of his policymaking.

This spring, Rivera is introducing a package of health bills he calls “non-partisan” and “commonsensical.” They include a bill to amend state laws to ban smoking 100 feet from the exits or entrances of any public or private educational institution and another that would mandate higher nutritional standards for any food marketed at a child by the inclusion of a toy.

No Smoking Near Schools

This week, the bill that would ban smoking 100 feet from the exits or entrances of any public or private educational institutions made its way out of the state Senate health committee. A vote on the bill could be imminent.

Current state law bans smoking inside and on the grounds of public and private schools, day care and vocational schools, but does not specify a protective area around entrances. The health department would enforce the new law Rivera has proposed; violators would be fined up to $2,000 per violation.

The Assembly’s health committee is expected to review the bill in two weeks. “I can’t imagine anyone would oppose this. This is about smoking near kids. It is a very sensible bill,” said Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz, the bill’s sponsor in the Assembly.

Rivera said he recently took a walk around the Bronx with school kids to take a look at cigarette advertising from their perspective. He said he saw a lot of advertisements in neighborhood delis directed right at their eye-level.

The Partnership for a Smoke-Free City collaborated with Rivera on the legislation and other community efforts.

“He has been a tireless advocate for the health of Bronx youth and all Bronx Residents,” said David Lehmann, the Partnership’s Bronx Borough manager.

Food Marketed At Children

Rivera has also introduced legislation that has come to be known as the “Happy Meal Bill,” which would mandate higher nutritional standards for any food marketed at a child when accompanied by a toy.

Assemblyman Felix Ortiz, a fellow Bronx politician sponsoring the bill in his chamber, said he thinks the legislation is important for every community in the state. “This obesity problem does not discriminate against age or ethnicity,” he said. “Corporate America has to have more of a conscience about what it supplies and parents need to be responsible as well.”

With 17 percent of American children now considered obese, both Rivera and Ortiz say the cost of treating the health problems associated with childhood obesity are skyrocketing. Nationally, the annual cost of providing inpatient treatment to obese children increased from $125.9 million in 2001 to $237.6 million in 2005.

The bill, like others being weighed or passed around the country that seek to either ban toys or somehow regulate how food is marketed to children, faces opposition from food companies, including McDonald's.

“The issue is much more complex and we are committed to giving families choices," said Cheryl Forsatz, a spokeswoman for McDonald’s.

Rivera’s bill sets specific guidelines for any meal marketed with a toy. A restaurant may only offer an incentive item in combination with the purchase of a meal when the meal is less than 500 calories; has less than 600 mg of sodium; and derives less than 353 of its total calories from fat, less than 10 percent of total calories from saturated fats or less than 10 percent of calories from added sugars. It also must contain 1/4 cup of fruits or vegetables or one serving of whole grain products.

If the restaurant fails to meet the standards, they would be forced to remove the incentive item. First time violators would face a fine of between $200 and $500; repeat offenders could face fines up to $1,500.

So far, the only legislator to voice opposition to the bill is state Sen. Ruben Diaz Sr., also of the Bronx.

“Parents struggle to do what’s best for their children, and at least so far, in this country parents are not dictated to by local elected officials about how to feed their children,” Diaz wrote in an email newsletter. He questioned the right of elected officials to “tell moms how they should feed their children.”

“If parents want to feed their kids horrible stuff, god bless America, they can do that,” Rivera responded. “But we know kids develop their eating habits early on and they should be given the chance to eat healthy.”

Transforming Bronx Health

Dinowitz said he attributes the Bronx’s position as the unhealthiest county to a number of factors. “There is the economics, we have certain facilities that are not conducive to health, we have all the highways and waste transit,” he said.

Rivera agrees and said that as much as he is focused on educating Bronx residents about what they can do as he is working to fix things they may not have as much control over.

“We have two tactical strategic goals,” Rivera said. “The first is to start being better educated overall. But we need to make sure we have access to fresh fruits, access to free or low-cost places to exercise, low cost healthcare. We need to minimize pollution that raises our asthma rates.”

In June 2011, Rivera partnered with Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. to launch the Bronx Changing Attitudes Now Health Initiative, bringing together members of the public with health organizations, providers, activists and community centers, with the goal of promoting healthy routines and setting personal health goals.

Rivera’s staff also worked to identify the farm stands and green markets in his district and sent out a flyer with the locations while inviting constituents to come meet him at certain times to talk about health. He hopes to utilize city funding to bring more green markets and vegetable stands to the district. His office is also working with beverage companies to provide the borough with healthier options, lower calorie drinks and more water.

“It takes all these things happening at the same time,” Rivera said.

Health Problems Plague City Cab Drivers

Photo by Jonathan Camhi

Marcelo Villagran administers a glucose test to driver Rafael Fernandez, age 62.

Ramon Mosquea, a 58-year-old heavy set Dominican, looked away nervously and winced as a small needle pricked his finger to draw blood for a glucose reading.

A couple of drops of his blood were inserted in a glucose-monitoring machine. The reading revealed that Mosquea, a cabbie for 20 years, had a blood glucose level of 206 milligrams per deciliter – a level high enough to diagnose him as diabetic.

“Wow!” Mosquea exclaimed when he saw his reading. “It’s never been that high before!” he said in Spanish, promising he’d make an appointment with his doctor as soon as possible.

Taxi drivers like Mosquea are highly susceptible to a number of health problems because of their sedentary lives spent sitting behind the wheel, studies have found. Drivers are often forced to eat on the go, making fast food their easiest option. Few of them get any exercise whatsoever, and often suffer from back, hip and leg pain from sitting in a car all day. This lack of exercise combined with a bad diet has led to high rates of diabetes and high blood pressure among cabbies, according to health experts. Many of them even have kidney problems because they frequently can’t find a place to park when they need to use a bathroom.

Vulnerable Population

A 2001 survey by the New York Taxi Worker’s Alliance found that more than 20 percent of drivers had cardiovascular disease or cancer.

And it is often difficult for taxi drivers to get the health care they need. Another study conducted by the city council in 2009 found that 52 percent of the city’s cabbies are uninsured, twice the rate of the average American.

Drivers often face language and cultural barriers to health care access as well. A 2006 study by a taxi industry consultant found that 91 percent of the city’s taxi drivers were born in another country.

But fortunately for drivers like Mosquea, hospitals and healthcare initiatives across the city are offering an increasing number of free health screening and information programs aimed specifically at taxi drivers.

Making Health Services Available

Mosquea’s glucose test was provided by Lincoln Hospital’s taxi driver outreach program. Maria Ramos, who founded the program, is the daughter of a cab driver who died of a heart attack.

“He never took care of himself,” she said of her father. “Every day he would say his chest hurts, his back hurts.”

Ramos said that demand for the taxi drivers health program has been steadily growing. The program visits taxi bases in the Bronx providing screenings, health information and flu shots. Lately Ramos has been getting requests from taxi bases in Queens and Harlem for the program to provide services there as well.

Part of the reason the program is in such high demand, Ramos said, is because most drivers work 60 to 70 hours per week, and they rarely have the time to go see a doctor. She remembers sometimes her father would come home for only a half an hour of sleep before heading out for another shift. Many taxi drivers also have stress-related problems from the long work hours spent navigating New York City’s hectic traffic.

“Many of them need to see a psychiatrist,” Ramos said.

Rafael Arias, a 62-year-old cabbie who has been driving taxis for 17 years, also received a glucose and blood pressure screening from Lincoln Hospital’s program. He said that a year and a half ago he had to have surgery because of a buildup of blood in his brain. The doctor told Arias that without the surgery he could have had a stroke. Arias said that he felt a great deal of stress from work at the time, and that his stress was partially to blame for his condition.

“If the blood went over here, I’d be dead,” Arias said, pointing to his right temple. “The doctor told me I’m a very lucky guy to be alive.”

Providing Services

Marcelo Villagran, an outreach coordinator at Lincoln Hospital, administered glucose tests for Mosquea, Arias and other drivers at the Prestige Car Service on Webster Avenue in the Bronx on a recent Tuesday. Villagran has been partnering with Maria Ramos to screen drivers for high blood pressure and glucose at taxi bases across the Bronx for four years now as part of the hospital’s taxi driver health outreach program.

That Tuesday Villagran turned the entry hallway of the Prestige Car Service taxi base into a small medical clinic. The drivers lined up to receive their free screenings from Villagran, who also gave out doctor referral forms and information pamphlets in both English and Spanish on diabetes and heart disease. He also gave the drivers $25 gift cards to supermarkets to discourage them from eating fast food, as well as cases of water bottles, telling them to drink water instead of soda.

One of the drivers said that he hadn’t seen a doctor in three years. Many of them said they don’t regularly see a physician, and rely on programs like Lincoln Hospital’s for their health care.

Even Rafael Arias said that he hadn’t seen a doctor since his brain surgery a year and a half ago. But after his blood pressure reading from Villagran was much higher than normal, Arias said he would try to set up an appointment soon to see one.

Hazards of the Job

Villagran said that more than 60 percent of the drivers at any given base have high blood pressure, more than twice the rate of average Americans.

“All of the drivers, they drink all soda and beer, they don’t eat healthy, they don’t exercise,” said Jose Hernandez, who manages the Prestige Car Service taxi base.