(photo: Marc A. Hermann / MTA New York City Transit)

Google Maps estimated an hour-and-a-half for a trip from near City Hall to a location in Southeast Queens, leaving at 5:30 p.m. on a recent Tuesday. On the E train to its final stop and a bus crawling along jam-packed Merrick Boulevard, the trip took about an hour longer, two-and-a-half hours from door to door.

“Now you know what we go through every day,“ City Council Member I. Daneek Miller told Gotham Gazette following that night’s event, which he co-hosted with Council Member Donovan Richards and focused on, what else, transportation.

The commute to and from downtown Manhattan that the Council members and some of their constituents face was part of the motivation behind the town hall, set in the outer reaches of the city and called to examine the challenging state of public transit in St. Albans, Laurelton, and surrounding neighborhoods - often referred to as a “transportation desert.”

In a recent op-ed for Crain’s New York Business, Miller laid out the extent of the problem: people from Southeast Queens spend roughly 15 hours a week commuting, 238 percent more time than the average New Yorker.

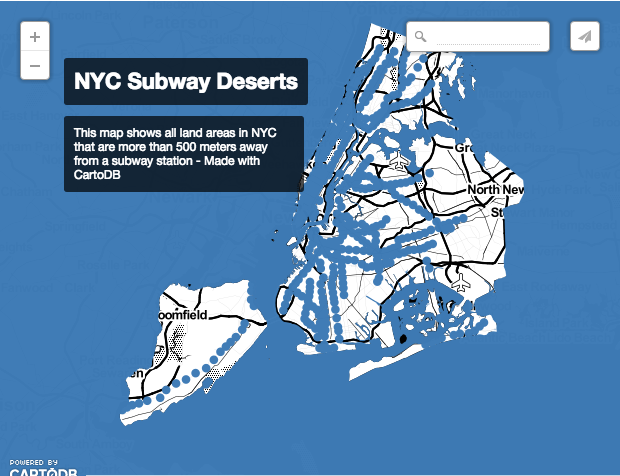

The residents of the area share this plight with several other neighborhoods considered transportation deserts because of their lack of public transit options - places including the Rockaways, the North Bronx, and the South Shore of Staten Island.

With the subway map sure to stay mostly as it is, communities in greatest need of good transportation options that can get residents to the city’s main jobs centers are reliant on a bus system lacking in capacity and dependability. Even though 97 percent of the city‘s population lives within a quarter mile of a bus stop, the collective problems with the service--it is one of the slowest systems in the nation and the slowest among big cities--render residents far removed from subway lines and feeling helpless.

With increased scrutiny of transportation deserts and lengthy New York City commutes come increasing calls for creative bus solutions: with more selective bus service (SBS) and bus rapid transit (BRT) at the forefront.

[NYC "subway deserts" - map by Chris Whong)

[NYC "subway deserts" - map by Chris Whong)

According to an audit released by Comptroller Scott Stringer in April, buses are not just slow, they are also often late: Stringer‘s study revealed that more than 30 percent of the city’s express buses do not run on schedule. Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island are hit the hardest, the comptroller said. The report also found that the MTA had inconsistent inspection standards for wheelchair lifts across their bus fleet, which, in addition to failing disabled riders, also slows bus time.

“This is more than just a statistic,“ Stringer said at the press conference unveiling his audit, “a late bus could mean a missed job opportunity, missed wages, or missed time with children.“

One possible antidote for lagging buses and transit hungry commuters is Bus Rapid Transit, and the idea is gaining momentum, as the Miller-Richards town hall showed. The questions ahead are about political will and community buy-in toward expanding BRT in New York City. BRT was a piece of a recent City Council hearing on transportation deserts, but the city’s Department of Transportation has already been made to study BRT through a law passed in the Council and signed by Mayor de Blasio that will lead to a report on areas where BRT should be implemented.

Started in Curitiba, Brazil in 1974, BRT was originally formulated as a cheaper alternative for a city that didn‘t have the money to build a subway. In its fullest form BRT combines a variety of features to make it operate at a speed comparable to light rail (an option also talked about for Queens and Staten Island). Long accordion style buses--in Curitiba they hold up to 250 people--shoot up and down bus-only lanes of large streets, stopping at intervals akin to a subway line (rather than the shorter ones of typical bus service).

Traffic signals have sensors in order to hold green lights for buses approaching intersections. People pay their fare before they board the bus and stations often feature elevated platforms or curbsides that coincide with the floor of the bus, making it quick and easy for elderly or disabled people to board. All this amounts to more on time, reliable, and efficient bus service.

Since the turn of the century cities across the globe including Paris, Istanbul, Bogata, and Los Angeles have all adopted BRT to curb car use and improve public transit overall.

Now, Mayor Bill de Blasio wants to bring BRT to New York as part of his efforts to help the city’s lower and middle classes. The argument also goes, of course, that if workers have shorter and easier commutes they are more productive when they’re at work.

”Bus riders are the most neglected part of our transportation system,” de Blasio’s policy book from his 2013 mayoral campaign reads. “Bus Rapid Transit has the potential to save outer-borough commuters hours off their commute times every week and stimulate economic activity in neighborhoods the subway system doesn’t reach.”

While it’s been somewhat slow to materialize, de Blasio’s pledge to bring New York City a “world-class bus rapid transit system” has been gaining steam. When signing the BRT study bill in May, de Blasio reminded that, “We all know that mass transit is particularly critical for those New Yorkers for whom resources are very tight, whose incomes are very tight - mass transit is their lifeline. It connects them to jobs, schools, everything.”

In March the state-run MTA and the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT) announced the official plan for the city‘s first full-scale BRT route on Woodhaven Boulevard, in Queens. The project will stretch 14.4 miles, cost around $200 million, and be fully operational by 2017. (By contrast, the Second Avenue subway is supposed to cover 8.5 miles, cost upwards of $17 billion, and be done at a to-be-determined date.)

Previously the two organizations’ efforts to speed up bus time came in the form of Select Bus Service, a paired down version of BRT that also utilizes off-board fare collection, along with traffic signal priority, semi-exclusive bus lanes, and longer distances between stations. The first SBS route was launched in 2008 on the Bx12 on Fordham Road in the Bronx, and has enjoyed relative success. According to statistics collected by the MTA one year after the launch, running times increased up to 19 percent, ridership by 8 percent.

Over the past seven years the MTA and the DOT have added seven other SBS routes, including ones going up First Avenue and down Second Avenue in Manhattan. All routes have enjoyed faster service and a 2013 DOT report claimed that SBS had saved eight million hours of travel time.

Still, SBS is not BRT. The former appears more suited for the busier sections for the city, the latter for moving people from the city’s outer reaches to its transit and business hubs.

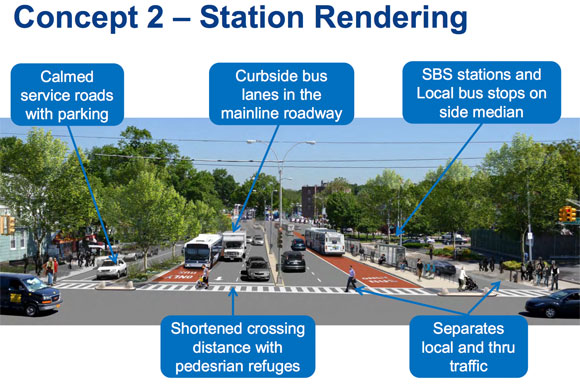

With the Woodhaven route, which will have exclusive lanes and robust, fully-outfitted stations with shelters, seats, and real-time information on bus arrivals (along with off-board fare collection and transit signal priority) the city is setting a new standard for its above-ground transportation. The fully exclusive bus lanes, which will also allow traffic signal priority to be more effective, are particularly exciting given that Kevin Ortiz, spokesperson for the MTA, told Gotham Gazette that traffic congestion and red lights are the top two causes for bus delays.

[Woodhaven BRT rendering, via NYC DOT]

[Woodhaven BRT rendering, via NYC DOT]

The line, which will run north-south, perpendicular to the A, E, F, J, M, R, and 7 trains, is indicative of the type of improvements BRT could offer in the so-called “outer boroughs.” Joan Byron, Director of Policy at the Pratt Center for Community Development and a member of the advocacy group BRT for NYC, sees this improvement as imperative to the economic empowerment of New York’s outer-borough residents.

“We have a problem right now of people not being able to get to their jobs and employers not being able to get to their workforce. Work locations are shifting. Job growth is much faster in the boroughs than it is in Manhattan…and the subway system isn‘t set up to serve them. You can do things with BRT that would take decades to do with rail,“ Byron told Gotham Gazette.

As it stands, she explains, “if you live some place like Far Rockaway…the number of jobs that are within a reasonable commute range for you are much smaller than if you live someplace like Park Slope.”

The Woodhaven line plans to change that for its service area. BRT lines along the North Shore of Staten Island (something City Council Member Debbie Rose called “a necessity, not an amenity”) and Southern Brooklyn—two possible routes the MTA and DOT are investigating—would also serve similar purposes.

Council Member Donovan Richards, who represents part of the area the new BRT route will serve, sees this project as only the beginning. Ultimately, he wants a full-scale BRT network throughout the city, viewing the issue as one that is also key to environmental justice.

“[BRT] needs to become as natural as breathing air,“ he said to Gotham Gazette after the town hall. “We have got to remember that if we don’t get cars off the road, climate change is going to wipe out communities in New York City. Overall the city needs to adopt it,” he said, referring to BRT.

[Rates of car ownership, via NYC EDC]

[Rates of car ownership, via NYC EDC]

Richards, along with city DOT officials, recently had lunch with and gave a tour of the planned Woodhaven route to a federal transportation secretary. U.S. Senator Charles Schumer has promised to push for federal funding.

The excitement continued into May when the mayor signed into law the new BRT-related bill.

According to the City Council website, “Under the bill, DOT would work with the MTA and gather input with the public to develop a citywide BRT plan, due to the Council no later than September 1, 2017. The plan would consider areas of the City in need of additional rapid transit options, strategies for serving growing neighborhoods, potential intra-borough and inter-borough BRT corridors DOT plans to establish by 2027, strategies for integrating BRT with other transit routes, and the anticipated operating costs of additional BRT lines.”

SBS may continue to expand, and many note that it is a version of BRT, but the extent to which a strong BRT system will be implemented is unclear. In several other cities where the system has achieved success, says Joan Byron of Pratt, the build of these cities naturally accommodated the necessary BRT infrastructure.

“The places where that has been done, places like Bogota, Columbia, that model was implemented exactly in the parts of the city that have kind of a post-World War II physical fabric and development pattern. The street there for the main bus line, the Transmillenial, is twelve lanes wide. Pedestrians cross that street on over-passes. It wasn’t a big jump to put dedicated lanes in the center region and to have physical stations that are actually enclosed.”

Woodhaven Boulevard, eight lanes wide and notoriously hazardous for pedestrians (the station islands to be installed in the middle of the avenue also act as a safety measure), is at least somewhat similar.

Council Member Brad Lander, the lead sponsor of the BRT bill, sees Manhattan’s First and Second Avenues as streets also appropriate for the full BRT service, especially given the MTA‘s recent announcement to forgo $1 billion in funding for the Second Avenue Subway project.

Most buses, though, don‘t operate on streets the width of a small highway (even dedicating a full lane of First or Second Avenue could prove quite contentious). For these routes Lander and Byron see smaller BRT-like features being incorporated into bus operation citywide on a case-by-case basis.

“The simple idea of off-board fare payment, that’s something we want to get to on every city bus,” Lander told Gotham Gazette. After that, he said, what is doable will depend on infrastructure features and funding.

Lander cited the SBS M86 route, the MTA‘s latest SBS addition, as a prime example. Even though there is not enough room for a dedicated bus lane (the bus runs crosstown on 86th Street in Manhattan), the MTA has already installed off-board fare collection and plans to add bus bulbs - protruding, bulges of sidewalk in front of bus stops, constructed so that the bus doesn‘t have to pull over when it picks up passengers. Stations are also equipped with real-time bus arrival information. A similar approach could be effective on smaller streets in the outer boroughs as well.

[A bus bulb, via Streetsblog.org]

[A bus bulb, via Streetsblog.org]

Council Member Daneek Miller is impatient, saying that his transit-starved constituents can’t wait a decade for BRT lines.

“There are 300,000 people in Southeast Queens who it’s talking an hour-and-a-half, an hour-and-forty-five minutes to get to their job in the city, who can’t wait 20 years for a change,” Miller said after his town hall.

Miller, who ran a transportation workers union before joining the Council, takes a slightly more cynical view of SBS. He says the recent buzz around BRT has led the city to overlook basic adaptations that could yield considerable results, like those he outlined in his op-ed, such as fare reform on the LIRR. For his constituents, Miller said, “BRT might be the second best answer. I can get to City Hall in 50 [minutes] on the LIRR; it takes me an hour-and-40-minutes using public transportation.”

Still, Miller certainly wants to see extended express bus service to Downtown Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn. He acknowledges infrastructure challenges of implementing BRT in some places, saying “We don‘t want to put square pegs in a round hole,” and that it is essential to have all the components, otherwise it won’t be BRT, but a “glorified express bus service.”

With an eye toward communities like those represented by his colleagues Miller and Richards, Lander points to the need for more options for commuters. Citing “low-income New Yorkers and communities of color” that “have disproportionately long commute times,” Lander said at the May bill-signing that “New Yorkers across the city – especially in transit-starved, outer-borough neighborhoods – need more mass-transit options. This law, and subsequent exploration of a Bus Rapid Transit network, will significantly improve public transportation access in the parts of NYC that need it most, at a cost we can afford, and help insure a more sustainable future.”

BRT and SBS advocates, like Lander, stand confident that their plan will deliver, and sooner than projected.

“I think it’s going to accelerate,“ said Byron. “For every elected official that will stand up and say ‘I want BRT in my district now,’ which all the Council members along the Q52, Q53 routes have said, you’ll get others that say, ‘Forget it, my constituents ride the bus,‘” Byron said, referring to hesitant Council members who she thinks will acquiesce.

When asked about the twelve year timeline in his BRT bill, a charged Lander replied, “the city - the DOT with the MTA - is already rolling out BRT at a pretty rapid rate...we are not waiting.“

****

by Colin O’Connor

@GothamGazette

@colinqoconnor93