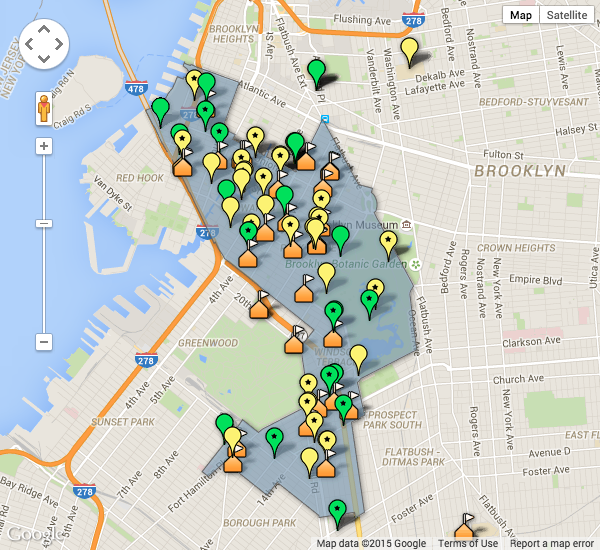

A screenshot of the new map launched by Council Member Brad Lander

They are notoriously over-budget and late. Capital projects - infrastructure investments in things like transportation, parks, libraries, and schools - regularly leave members of the public wondering if their elected officials are competent or honest.

On a large-scale, think 2nd Avenue Subway, 7-line extension, and East Side Access. But, there are also many, many smaller capital projects all over the city.

As participatory budgeting has taken hold in about two dozen New York City Council districts, residents can see capital spending and project progress on a small-scale, down-the-block basis from the very start. One of the keys to the “PB” process is that district residents themselves get to design and decide where government money gets spent in their neighborhoods. Still, it is not always easy to keep track of these projects, which can often take longer than residents would like.

Now, New Yorkers of the city’s 39th council district have a new government accountability tool at their disposal. And, it is one that could be a model to bring greater transparency and urgency to capital projects across the city. Brooklyn City Council Member Brad Lander has published a new comprehensive map of ongoing capital projects in his district, which stretches from Cobble Hill to Park Slope to Kensington.

The interactive map, now available on the council member’s website, designates projects both in progress and completed, and whether or not they were funded through participatory budgeting. By simply clicking an icon on the map, users can find out more detail about each project in particular, including what year it was funded, the amount allocated to the project, and its current completion status.

The tool, a Google Maps embed created by Pratt Institute summer intern Annie Levers (and a feasible project for anyone with a gmail account) is not being billed as the next big, highfalutin tech solution, but rather a simple common-sense step towards improving accountability in the city’s capital contracts.

The idea comes from desire for more transparency in the way that the city handles its capital projects. Discussing the tool and larger issue at hand, Lander points to the Parks Capital Tracker, introduced last year by the city Parks Department, as a good first step toward setting a new standard of transparency, but noted that council member-funded capital projects were still not included in discretionary funding information publicly provided the City Council.

Ideally, Lander considers the map a step toward a larger, more robust citywide system for tracking the ways in which public money is spent. Even though overhead costs were minimal and the data accessible to all council members, Lander does not expect his colleagues to follow suit and publish maps of their own.

“I think the long term answer is for the City of New York to provide a portal for all capital projects,” Lander told Gotham Gazette. “I am developing legislation that would require the city to provide something like this -- or the Parks Capital Tracker -- for all city capital projects, whether funded by an agency, City Hall, or by the Council.”

“I don't think the long-term answer is every council member developing their own map and database,” Lander said. Rather, “the long-term answer is a citywide system that tracks all capital projects.”

Such a system, Lander hopes, would be a resource for both individuals seeking information about a particular project in their neighborhood and for more formal research purposes, including the city’s own efforts to increase efficiency and accountability.

For instance, Lander offers that “it may be that a particular contractor works for three or four different agencies, but if you track it over time, you see that that contractor is persistently late or persistently coming in over budget. So there's a value in systems efficiency, there's value in meeting questions of equity: how's the number being spent in between neighborhoods; evaluating different priorities.”

This effort runs parallel to a broader theme within the administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio, Lander’s predecessor in the Council: simplifying and streamlining the city’s capital investments.

“I think [improved accountability] has been a theme in the de Blasio administration on the capital budget side,” says Adam Forman, of the Center for an Urban Future, a think tank. City Comptroller Scott Stringer released a report in February looking at the rates at which capital projects are begun in the fiscal year they are supposed to, showing some of the inefficiencies in capital processes over the past ten years.

Meanwhile, Forman adds that due to the time that it takes to design contracts, bid them out, and finally get shovels in the ground, the City Council often authorizes some $15 billion of capital spending a year, “knowing full well” that only some $8-10 billion will actually be contracted out.

Simply opening up the details of capital contracts to public scrutiny could contribute more pressure towards a model where, as Forman puts it, “the money that we authorize to spend, let's actually spend it in that fiscal year.”

Bolstering a sense of public stewardship

A second goal of the map will be more difficult to quantify than improved contracting accountability. Lander hopes that making information more available, and importantly, more digestible will help bolster a sense of public stewardship in capital projects around his district.

Although increased accountability will be a main selling point when presenting legislation to the Council, the map was originally born out of a desire to merely better present updates about ongoing participatory budgeting projects within the district.

Lander says that a key value add of participatory budgeting, currently in its fifth year in the 39th District, is that it “enables people to feel like stewards of pieces of the public realm. They develop the ideas for them, they lobby for them, and so they feel a stronger sense of stewardship around the projects that they voted and advocated for, so that they're eager to know their status.”

“Because people voted on them, we felt a responsibility to provide updates on where these projects are,” Lander said. “And until now, we just had a big [Microsoft] Word-like webpage, where you have to scroll down and you see each year's project and which ones won, and look at it, and there it is. Now that we're in year five, we realized that's not the best way to keep people updated.” Thus, the new interactive map.

Constituent Julie Bero, a Windsor Terrace resident and member of the District Committee for Participatory Budgeting, agrees that the map has a deeper potential as a tool for public education. “Just a few years into the process, I think the effectiveness of PB is not quickly clear because many of the projects are not yet complete,” said Bero.

The PB process is largely run as a volunteer effort, where delays and bureaucratic holdups can present a challenge to recruiting and retaining volunteers, and winning over skeptics. Bero explains that “so much in our culture is about instant gratification and some people have expressed frustration that projects that won funding early on aren't already done.”

Bero thinks that tools such as the mapping project could compensate for the lack of feedback for many projects so far. Bero hopes that in several years, when a variety of PB projects finally are really bearing fruit, that a sense of communal stewardship and accomplishment may be more visible. “But in the meantime, this map can help residents of our district to understand the progress that's already been made and look forward to what's on the horizon.”

***

by Brit Byrd, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette