Wanda Hernandez readily admits she’s been in and out of New York City Housing Court because she’s “always in arrears with rent.”

She receives rental assistance from the city’s HIV/AIDS Services Administration (HASA), but it was recently reduced to $43.53 a month. And although her rent was frozen, thanks to the city’s Disability Rent Increase Exemption, she struggles to come up with $900 each month to pay her portion of the rent.

“It's not like I don’t know how to budget,” she said. “There’s just not enough money.”

Hernandez is one of more than 10,000 New Yorkers who will be eligible for new “housing protection” for low-income residents living with HIV or AIDS.

The measure stipulates that residents who are permanently disabled by HIV/AIDS and receive HASA rental assistance will pay no more than 30 percent of their income toward their rent.

The initiative marks a complete about-face from the city’s recent history on the issue. Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg complained four years ago that the rental cap would add 10 percent to the $150 million that the city was already paying for the rental assistance program. He successfully urged then-Gov. David Paterson to veto legislation creating the cap.

Two years ago, a rental-cap bill failed to muster enough votes to pass in the state Senate. Bloomberg had once again opposed the legislation.

But new administrations at the city and state level agree the rental cap is critically needed.

“This action will ensure that thousands of New Yorkers living with HIV/AIDS will no longer be forced to choose between paying their rent or paying for food and other essential costs of living,” said Gov. Andrew Cuomo in announcing an agreement with the city to establish the cap. He proposed a $9 million budget amendment last week to cover the state’s share of the cost.

The cost is estimated at $20 million annually. New York City will pay 71 percent of the cost of the program and the state will cover the remaining 29 percent, according to the plan.

“We are committed to lifting up the most vulnerable among us,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio in announcing the measure. “This is the mark of a compassionate city."

Hernandez was diagnosed with HIV nearly 20 years ago. Without a cap on her rent payment, she is left with about $300 a month to live on. If she were to ask HASA to help her pay for other expenses, such as her electric bill, the assistance would be deducted from her monthly stipend, which “defeats the purpose,” she said. And HASA rejected her application for a “one shot” payment to help her get caught up on unpaid bills, she added.

“They want to make the client look bad,” she said, adding that HASA has red-flagged her as having a history of falling behind on her rent, even though the agency knows its inadequate assistance is the root of the problem.

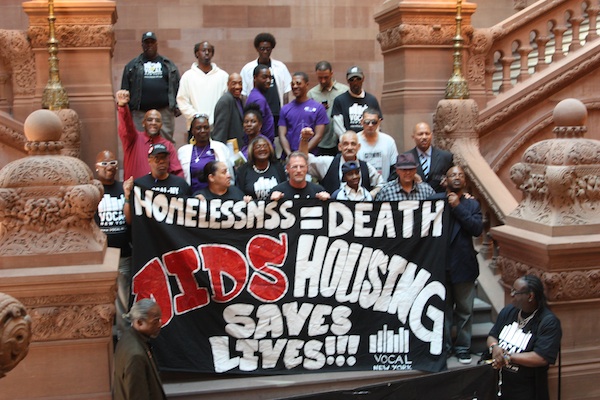

Hernandez serves as chairperson of the board of directors for Voices of Community Activists & Leaders (VOCAL-NY), a statewide grassroots organization advocating for low-income people living with HIV/AIDS.

VOCAL-NY was a driving force behind the campaign for the cap. Sean Barry, the organization’s executive director, credited the campaign’s success to an “ensemble effort” of groups ranging from the United Healthcare Workers East labor union to the national Human Rights Campaign.

People who receive federal housing subsidies, such as Section 8, have received the 30-percent rent cap for many years. City and state officials attempted in 2006 to eliminate that cap for HASA clients living in federally subsidized housing. They backed off after lawyers from the Housing Works organization secured an injunction to bar the move.

HIV/AIDS activists have been lobbying to win the rent cap for all HASA clients for several years. HASA provides some form of rental assistance to more than 26,000 clients.

Without the cap, many people with AIDS are exposed to the possibility of becoming homeless, activists argue. On a psychological level, the stress of generating enough rent money to avoid homelessness takes a toll on a community of people who’s health is already compromised, they say.

“Housing is health care,” said Janet Weinberg, interim CEO of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) organization. “The only way we can expect people living with HIV/AIDS to stay healthy is by ensuring that their housing is secure and safe.“

State Sen. Brad Hoylman, D.-Manhattan, who like his predecessor, Sen. Tom Duane, championed legislation to create the cap, praised the measure as a “smart, cost-effective public health policy.”

Studies have shown the rent cap will pay for itself by preventing the costs associated with homelessness and by generating significant Medicaid savings, he said.

Advocates of the cap often point to a 2009 analysis conducted by Shubert Botein Policy Associates which concluded that the $20.7 million cost of the cap would be offset by more than $21 million in rent payments that would otherwise have been in arrears and the costs of relocating HIV/AIDS people who would be displaced by failure to make rent payments.

Many people with HIV/AIDS pay as much as 70 percent of their income for rent – income that often comes primarily from disability insurance. (See related commentary in Opinions section)

As to when the cap might be available to HIV/AIDS renters, Lyndel Urbano, GMHC manager of governmental affairs, suggested that a realistic timeframe would be the end of June, after City Council votes on the budget.

“We need to be realistic about how the process works,” he said. “There’s a need for a bit of patience.”

Photo credit: VOCAL-NY.