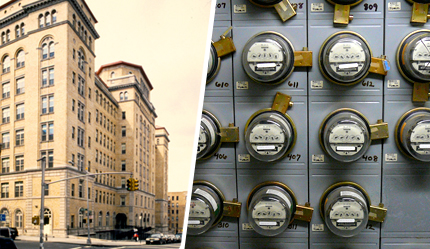

The Women's Housing and Economic Development Corporation is demonstrating how

older buildings, such as this 85-year-old affordable housing complex in the Bronx,

could be retrofitted to be more energy efficient.

Across the city, tenants are turning off their air conditioners and switching to compact fluorescent lights. Yet even the most energy-conscious renters have no authority to demand changes to inefficient out-dated building systems that are wasteful, costly and polluting. They cannot require their landlords do things like replace old boilers, install Energy Star appliances and low-flow showerheads, or seal walls and roofs that leak air and precious heat in the winter.

The absence of these conservation measures in New York's old buildings drives up costs and enlarges the city's already sizable carbon footprint. Buildings are responsible for nearly 80 percent of New York City's total carbon emissions, significantly more than automobiles. And this city is not alone. Nationally, buildings consume more than 60 percent of the electricity generated and account for at least 35 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions that cause global warming.

The mayor's Office of Long-term Planning and Sustainability has called for fully one third of city's planned carbon reduction by 2030 to come from increasing the energy efficiency of buildings. In this, though, New York faces a unique problem: We have a finite amount of land, and 90 percent of buildings that stand today were constructed well before the availability of new energy efficient technology. This means that reducing building emissions requires retrofitting existing buildings now.

Currently programs exist to help property owners make this kind of investment. Unfortunately, though, there is little incentive for them to take advantage of that help.

Who Pays? Who Saves?

Currently, property owners have little incentive to trim energy costs. New York's Rent Guildelines Board allows owners to pass along building operating expenses to their tenants. This year, based largely on skyrocketing energy costs, it is decidedly more expensive to operate a building than in years past. So, the board, which regulates rents for over 1 million city apartment dwellers, last month enacted the largest increases in nearly two decades.

The rent increases not only placed the financial burden of high utility bills on tenants, most of whom can ill afford them, but also struck another blow to a city rapidly losing affordable rental housing. If public policy simply allows building owners to saddle tenants with increased energy costs, owners have no incentive to do the right thing. Why trade in your SUV if someone else is paying to fill the tank?

Increased energy costs imperil both the affordability of housing and owners' profits. The answer though, is not higher rents, it's lower costs.

The sustainable solution is for property owners to upgrade their buildings and lower their utility bills. It's time to recognize the new reality of high fuel costs and facilitate comprehensive reductions in residential energy use that would save money for owners and tenants alike. Genuinely energy-efficient buildings hold the greatest promise for maintaining housing affordability and profitability, not to mention saving the planet.

Conservation Strategies

The only way to effectively reduce utility-related building expenses is through energy-smart building upgrades. Buildings need efficient heating and ventilation systems; apartments require Energy Star appliances. Building envelopes should be sealed to reduce heat loss in the winter and heat gain in the summer.

Identifying the most cost-effective upgrades requires some engineering calculations, but it is far from rocket science. The analysis and the improvements can be affordable through programs already in existence: in New York State, primarily through the New York Energy Research and Development Authority, or NYSERDA, and via the federally funded Weatherization Assistance Program. These two stable and well-funded programs together amount to Medicare for aging buildings!

NYSERDA, through its Multi-Family Performance Program for existing buildings, provides owners with consulting services and cash incentives to develop an energy reduction plan aimed at reducing energy costs by at least 20 percent. For example, the completion of an acceptable plan in buildings with over 100 apartments triggers an initial $5,000 to $10,000 payment (less for market rate buildings, more for affordable). When the energy plan is 50 percent complete, owners receive from $300 to $800 per unit and, upon completion, another $300 to $400 per unit.

So, if a property owner wants to install a new energy efficient boiler costing $270,000 in an affordable building with 130 apartments, NYSERDA would provide, through these tiered incentives, cash covering between 40 percent and 60 percent of the upfront cost of the boiler, and below market financing for the balance. In this scenario, NYSERDA could pay up to $166,000 and provide financing for remaining $104,000.

Energy consultants estimate that an efficient boiler, correctly sized to heat a 130 unit building and its common areas would save the owner about $29,000 in the first year alone. This translates into a full payback on the owner's $104,000 investment in less than four years. The immediate energy savings, coupled with low financing costs, will provide an owner with ample cash to pay back the loan, while saving energy costs. After the loan is paid off, the owner is left with more savings -- and a vastly less polluting building.

Learning from the Bronx

My organization, WHEDCo, is a nonprofit that owns and develops affordable housing in the Bronx. Nonprofit affordable housing providers have virtually no cushion against rising expenses. Our tenants cannot afford to shoulder increased costs at a time when their wages are stagnating or declining. Energy efficiency for all of us is a matter of survival. So, we are into our second year of a three-year cellar-to-roof energy "retrofit" of our 132 apartment, 10-story, 85-year-old building.

The first year's energy upgrades have already reduced costs for WHEDCo and the tenants by 10 percent. We replaced 132 refrigerators with Energy Star models, installed low-flow showerheads, air-sealed exterior doors and the basement ceiling, upgraded both apartment and building-wide lighting; and weather-stripped entrances. We have fully funded the $167,000 expense for these upgrades through NYSERDA, the Weatherization program, the Deutsche Bank Americas Working Capital Program, Citigroup Partners in Progress and a few foundation grants.

We plan to invest an additional $500,000 in energy-saving retrofit items like a co-generation system (also known as combined heat and power), replacing out-dated toilets, installing constant air regulator dampers on apartment vents, purchasing compact fluorescent bulbs in bulk for our low income tenants and more. All of our planned year two investments will yield a combined energy savings of $107,000 in the year immediately after installation -- and every year thereafter. This work will reduce energy consumption and costs by as much as 30 percent.

As this demonstrates, programs such NYSERDA -one hopes others as well -- can quickly cover the expenses of even the costliest upgrades. Next year when the Rent Guidelines Board meets, before considering any rent increases, it should require evidence that owners have taken substantial measures to reduce the costs and emissions of their properties. Freezing rent increases may not affect global warming, but linking rent increases to owner investments in energy efficiency savings is a two-fisted approach to the problems of a new century.

Nancy Biberman is president of the Women's Housing & Economic Development Corp. (WHEDCo).