Related: |

Listening to Mayor Michael Bloomberg and New York City Council Speaker Gifford Miller fight over garbage this month, the casual observer could be forgiven for thinking that the mayor’s entire citywide plan for garbage centered on a single pier on the Upper East Side. The development of trash policy has recently gotten bogged down over the mayor’s call to use several such piers as places for garbage trucks to unload onto barges. The dispute reached a climax on June 22nd when Miller failed to block the opening of the so-called marine transfer station in his district.

But with this diversion out of the way, officials and environmental advocates are turning back to the central issues of a plan that is rich in details on how to move the city's trash around, but, critics say, short on everything else.

“It’s our hope that the controversy is over and we can get back to the overall business of this plan, which is how do we deal with the rest of this 50,000 tons per day of waste,” said Eddie Bautista of the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods.

In the past, the city has dealt with waste by burning it, or burying it. Now Bloomberg is focusing on shipping it away. But the City Council has published its own plan that lists recycling as its major priority, and criticizes the mayor’s plan for failing “to put forward any real programs or policies that would reduce waste and increase recycling.”

Councilmember Michael McMahon, head of the council’s sanitation committee, will soon begin negotiating with the mayor over the council’s concerns. His hope is that by September a compromise plan will be worked out -- and that it will prominently feature recycling.

ARE NEW YORKERS RECYCLERS?

In theory, increasing the amount of garbage that is recycled is a goal that everyone can agree on. But how to do so is not necessarily simple, and officials differ on how much recycling the city can reasonably expect.

Currently, about 20 percent of residential waste in New York is recycled. City life poses serious challenges for those planning ways to raise this rate. Most New Yorkers live in apartments where there is often little space to set up bins to separate garbage. And although residents are legally required to recycle, apartment-dwellers are relatively invulnerable to tough enforcement measures, because it’s hard to find out who in a large apartment building isn’t recycling in order to fine them.

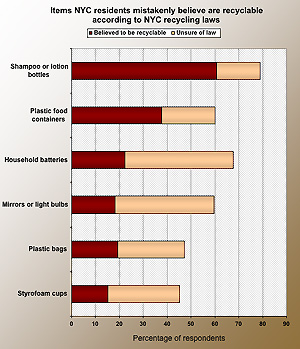

Further, many New Yorkers are confused about what is recyclable. A recent survey conducted for Gotham Gazette by Baruch College's eTownPanel found that about 85 percent of city residents knew that newspapers are recyclable, but less than half knew that aerosol cans are, and only about 40 percent knew that wire hangers are. At the opposite end, about 40 percent knew that plastic deli containers are NOT recyclable, and a mere 20 percent knew that they cannot recycle shampoo and lotion bottles. (For details on the survey and to see charts, click here)

Some believe that a mixture of education and enforcement could significantly raise the rate of recycling in the city, but Mayor Bloomberg is skeptical that these will make much difference.

“The more you recycle the better off you are,” he told WABC-FM earlier this month. “But most [of the city’s waste] is going to get thrown out.”

THE MAYOR’S ATTITUDE: SKEPTICAL OF RECYCLING

The mayor’s attitude towards recycling has displeased recycling advocates in the past. Facing a daunting budget gap in 2002, the mayor decided recycling was a luxury the city could not afford. The city suspended its glass and plastic recycling programs.

It wasn’t the first time that the city had cut back on recycling efforts in tough times. When the environmental benefits of recycling are measured against its economic drawbacks, the economics generally win out.

“Whenever something bad happens, recycling gets pushed back,” said Carmen Cognetta, legal counsel to the City Council’s solid waste committee.

Recycling has always been vulnerable to budget cuts because historically it has been more expensive that dumping garbage in landfills. While taking trash to a landfill costs significantly more than it does to take it to a recycling plant, the higher cost of collecting recyclables more than offsets these savings.

Advocates have long hoped to develop a way to make recycling as cheap as waste disposal. If achieved, this goal of “cost parity” does work to protect recycling programs. The city didn’t consider eliminating paper recycling in 2002, for instance, because it was actually getting paid by private companies for the recyclable paper, rather than having to pay.

THE MAYOR'S PLAN: MAKING RECYCLING PAY OFF

The mayor's overall garbage plan calls for the city to load its waste onto rail and barges and ship it out of the city, instead of relying as heavily on trucks as the city does now.

Environmentalists and activists from low- income neighborhoods have thrown their support behind the plan, because it decreases the city’s reliance on trucks, and spreads the burden of waste management throughout the city. The main criticism of the plan has been that it does not address where to send the trash, thus doing little to deal with the city’s fundamental trash related problem: its reliance on increasingly pricey landfills in distant places. (report in .pdf format)

For recyclables, however, Bloomberg’s plan does identify what it says is a good place to send waste. The city has forged a long-term relationship with recycling company Hugo Neu, in order to secure stable, favorable rates. As incentive to sign the 20-year contract, the city has agreed to invest $25 million to help Hugo Neu build a recycling facility in Sunset Park. Savings from the terms of the contract, the city believes, will more than offset the cost of the plant.

As the cost of recycling decreases, the cost of waste disposal will be increasing, thanks to the capital investment necessary to make the transition to new forms of transportation. This, some see as a good thing.

“This short-run increase in waste disposal costs, coupled with a new contract that lowers the fee paid for processing the city’s recyclables, alters the economics of waste management increasingly in favor of recycling as a cost-competitive alternative to disposal,” wrote Elisabeth Franklin and Preston Niblack of the Independent Budget Office in a recent analysis. (report in pdf format)

The analysis concludes that, all things being equal, the mayor’s plan will make the cost of recycling roughly equal to that of waste disposal.

While Bloomberg’s plan may end up creating a strong financial incentive to recycle, critics still deride its lack of a coherent recycling strategy.

"Exporting trash is one little piece of solid waste management. The city has a golden opportunity to commit in writing to innovative waste prevention, reuse, and recycling initiatives,” said Majorie Clarke, co-chair of the New York City Waste Prevention Coalition. “That's the guts that they're missing."

THE CITY COUNCIL’S ALTERNATIVE

Are New Yorkers Recyclers? Click here for details and charts |

The City Council aims much higher than the mayor in terms of recycling. Bloomberg’s goal is to have 26 percent of residential waste be recycled by 2010 and a 33 percent residential recycling rate by 2024. The council plan is much more ambitious, calling for an increase in residential recycling from 20 to 25 percent by 2007, and by 2015 a combined residential and commercial recycling rate of 70 percent.

Increasing recycling rates not only has environmental benefits, it has economic advantages as well. The more residents can be taught what is recyclable -- and either encouraged or forced to do it -- the cheaper recycling becomes. Collecting garbage is less expensive than recycling because the same truck can gather more tons of garbage per route than it can of recyclables. This is partially due to the relatively low weight of recyclables – plastic weighs less than food waste. But the more recycling that ends up on each curb, the less it costs to collect each ton of it.

“If the city is successful in increasing recycling beyond recent levels, it may even become the cheaper alternative, creating a strong incentive to promote recycling as a way to hold down the total cost of waste management,” wrote Franklin of the Independent Budget Office. (report in pdf format)

The mayor’s plan brushes over this potential; there are few specific ideas for increasing recycling rates. By contrast, the council’s plan calls for establishing a division in every community board that will tailor recycling programs to the local level. A new city agency would oversee this, leaving the Sanitation Department – which proponents of the plan describe as insufficiently committed to recycling – out of all recycling education and outreach programs.

"[Recycling] is never going to flourish under Sanitation," said Cognetta.

But Benjamin Miller, former director (and current critic) of policy planning for the Sanitation Department and author of Fat of the Land, a history of the city’s garbage, doubts whether the council’s plan will be effective. Any recycling plan should set a single standard for the entire city, he says, rather than relying on individual efforts in each neighborhood. And the best way to have a citywide plan is to keep a single agency in charge of all waste issues.

“The plan proposes what I would argue are likely to be quite inefficient systems [that] reflect a flawed understanding of how a recycling system should be designed,” he said. “We have to keep it simple.” Miller believes the best way to increase recycling is to charge people for the amount of garbage they throw out, creating an incentive to reduce the amount of waste they produce by, for example, recycling more.

The council’s plan also calls for increasing commercial recycling rates, and attempts to establish ways to recycle or reuse materials that today tend to end up in landfills.

ZERO WASTE: BEYOND RECYCLING

Some of these strategies were discussed at a recent conference of recycling advocates held in downtown Manhattan. The conference’s focus was to formulate programs that go beyond recycling by increasing the scope of what can be recycled and reduce consumption in general in a comprehensive strategy.

Attendees noted the success of initiatives in California and Maine that reduced waste at the source. They suggested more aggressive citywide compost recycling and a surcharge on plastic bags. A similar “plastax” law in Ireland reduced plastic bag use there by 90 percent.

The city would need help in implementing some of these ideas. Any new tax, for instance, would need to be approved by Albany.

The council has embraced these principles as part of its plan. It is currently considering several actions, including a bill that would require manufacturers to take back and recycle, reuse or properly dispose of a percentage of the electronics they sell. Another resolution calls on the state to pass a bill that would expand the bottle deposit to more products.

Jordan Barowitz, a spokesperson for the mayor, told the New York Times that the administration is willing to consider substantive changes to its plan, and specifically cited adding measures to increase recycling. But council’s plan, he said, was “a gimmick. It doesn’t advance the negotiations at all.”

Garbage plans in New York are often written and rarely implemented, and there is no guarantee that the council and the mayor’s negotiations this summer will end up producing anything resembling either of their plans. But if the officials can navigate the ever-tricky politics of garbage, recycling advocates see the potential for an economic and environmental payoff in the ideas currently on the table.

Â