The Mayor Must Immediately Create a Just Reentry System for Those Leaving City Jails

The mayor at a pre-pandemic jail to jobs (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

The COVID-19 pandemic has served as another reminder that New York is a tale of two cities. The wealthy and elite were largely able to sequester themselves safely during the height of the pandemic and resume city life once infection rates went down. Many may again be removing themselves as cases rise. But the most vulnerable New Yorkers are still left without basic supports and services.

This is especially true for people released from city jails and detention centers. They were ignored when they were behind bars, where COVID spread at alarmingly higher rates than the rest of the city. Now, with the pandemic still with us and possibly worsening again, these New Yorkers leave the despair and neglect of jail to only once again have their needs discarded as they reenter society. We demand the needs of our formerly incarcerated fellow New Yorkers be met. There can be no equity and equality until we treat all individuals as human beings.

When COVID-19 hit, protecting people behind bars was largely dismissed. People who are incarcerated were largely ignored, even though, as The Legal Aid Society reported, city and state correctional facilities rapidly became epicenters of the virus.

Rapidly soaring covid cases in jails like Rikers and others forced attention to that population and calls to release incarcerated people to protect them from the dangerous conditions that left so many vulnerable to the virus. The city responded by releasing 1,400 people between March 25 and May 3. As of September 22, over 1,950 people had been released.

This may sound like a good outcome, but in fact the release of incarcerated people during the pandemic has exposed more sharply the injustice of New York City’s reentry programs.

People are released from New York City jails without the basic tools they need to reenter society, including a valid I.D., which is essential for securing housing and other services. Those returning home lack sufficient medication or immediate access to Medicaid coverage due to bureaucratic hurdles preventing the immediate transfer of their medication from jail. Perhaps most shocking of all, many people leave jail, despite the extraordinarily high risk of contracting the virus behind bars, which of course threatens to lead to further community spread given how many people come in and out of our jails.

These basic services could be addressed by the Mayor, who can utilize the IDNYC program to provide a valid ID and effectively transition people’s healthcare upon release from Rikers, while also mandating COVID-19 testing during the reentry process. To further ensure that New Yorkers can get their lives back on track once they leave jail, we must provide safe and stable housing options. Unfortunately, our very own government discriminates against formerly incarcerated individuals through the NYCHA permanent exclusion rule, which can prevent those with criminal records from securing tenancy. We must end this regressive and harmful policy, which disproportionately impacts Black and Hispanic New Yorkers.

We must also pair this change with an increase in affordable housing for those in the reentry process, and the city can and must increase the value of its housing voucher program to meet the fair market rates for housing unit rental prices, while also supporting existing City Council legislation to ban source-of-income discrimination from private landlords.

Establishing a just and wholesome reentry program is essential if we want formerly incarcerated people to fully return to society safely and prevent the recidivism that plagues our prisons and jails. So, Mr. Mayor: What are you waiting for?

***

Rabbi Barat Ellman is an anti-racism and criminal justice reform activist; a member of CAMMEERR, Children of Abraham, Martin, Malcolm, Ella, Emma, Rosa and Rose, a multiracial, cross-faith group; and of the Faith Leaders for Just Reentry Coalition of Trinity Church of Wall Street. Shawanna Vaughn is an activist, advocate, and organizer for human rights, and the Executive Director of Silent Cry. On Twitter @BaratEllman & @SilentcrySv.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

It’s Time to Bridge New York’s Digital Divide — Here’s How

Getting students connected is one part (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor’s Office)

Despite millions of dollars spent and a variety of initiatives undertaken, too many New Yorkers still lack reliable online access at a time when it is more important than ever.

Reliable and fast connectivity is not a privilege, it’s essential. Without it, homes and businesses simply cannot succeed amid this public health crisis, which has forced many to live much of their lives virtually – from remote working and telehealth, to online learning, shopping, and socializing.

The need to close the digital divide is now a mandate for elected officials at all levels of government. The telecommunications industry is eager to improve service across the state. Unfortunately, a patchwork of regulations stymie investments.

For example, a fee implemented on the fiber in municipal rights-of-way, passed as part of the 2019-20 state budget, makes it cost prohibitive to expand online service to areas most in need. Underground fiber provides the backbone of a strong online network. Also, a recently proposed E-LEARN bill would layer on additional costs. In addition, state lawmakers have twice rejected the governor’s proposed statewide plan to streamline permitting of small cells, the technology necessary to facilitate the deployment of the next generation of wireless connectivity, known as 5G.

Students across the state face immense challenges getting online as schools shifted to all-virtual instruction in so many cases. Over 700,000 students and 18,000 teachers reportedly lack adequate connectivity, and the problem is particularly acute among Black and brown communities.

In New York City alone, 40% of households across the five boroughs don’t have both home and mobile internet connections while 18% have neither.

5G will help address the digital divide with faster speeds, expanded capacity, and lower latency. The vast majority of Americans – 81% in 2019 – own a smartphone, making mobile devices an opportunity to address lack of connectivity, especially for young people, low-income individuals and people of color, who are more likely to rely on a smartphone as their primary means of online access.

Corporate philanthropy has rallied to help students in need throughout the pandemic, offering free or reduced-rate internet and donating WiFi hotspots and laptops. Now, elected officials and policy-makers need to facilitate the buildout of a small cell network that will increase coverage, capacity, and advance 5G. To do so, New York City must open a long-awaited reservation period – the time when authorized companies are allowed to bid on the right to use and lease city infrastructure (street and traffic lights and utility poles) to install telecommunications boxes and antennae — and the state Legislature must remove the barriers to deployment.

Reliable online service capable of transmitting large amounts of data is also critical to the success of telehealth, use of which increased exponentially in the pandemic’s early days and shows no signs of abating in popularity. NYC Health + Hospitals, for example, announced its telehealth visits had soared from just 500 in mid-March to more than 235,000 televisits by early June. Telehealth not only helps reduce costs, but also improves access to care in underserved rural areas. But good internet is essential.

Experts predict it will take years for New York and the nation to recover from the economic devastation wrought by the pandemic. Next-generation connectivity has the power to transform almost every aspect of modern life and the ability to generate millions of dollars in revenue and thousands of jobs across the state.

Remote working, telehealth, online learning, commerce, entertainment and essential services, like 911, are all dependent on connectivity. However, we face many obstacles with expanding wired and wireless networks. If the city and state are serious about addressing the digital divide, keeping residents safe, and setting businesses up for success, it is well past time to think bigger than simply making internet subscriptions more affordable. We need the tools capable of ushering us into a world of virtual possibility – we need to enhance the current 4G infrastructure and deploy 5G.

***

Ana Rua is Government Affairs Manager at Crowne Castle.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Trumpian Push to Overturn the Will of New York City Voters

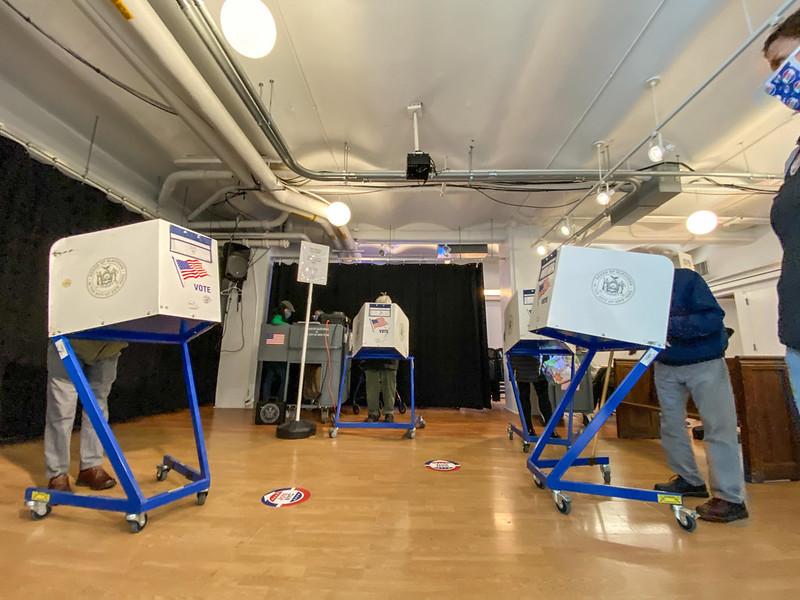

Voters having their say (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayor's Office)

While much of the nation is focused on Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the will of the voters in the presidential election through court challenges, delays, and proposed do-overs, a small group of politicians is seeking to do something similar in New York City.

At the beginning of 2019, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson established a Charter Revision Commission consisting of appointees of the Mayor, the Speaker, the Comptroller, the Public Advocate, and all the Borough Presidents. That Commission voted 13-2 to recommend, among other proposals, a new system of voting in city party primaries and special elections, called Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV). Only the Staten Island Borough President’s appointee and one of the Speaker’s four appointees voted against the proposal. RCV was then approved by almost 75% of those voting in the November 2019 municipal election and is now law in New York City, applicable to all City Council, Borough President, and city-wide primary and special elections. It’s set to take effect in 2021 when New Yorkers will elect a new roster of city government officials, including a new Mayor.

This is the way RCV works: voters choose up to five candidates running in a given race in their order of preference. If a candidate receives more than 50% of the first place votes, that candidate wins. If no candidate receives a majority of the vote, the one with the lowest number of first place votes is eliminated and that candidate’s votes are distributed to the second place choices of their voters. If no candidate still receives more than 50% of the votes, the remaining candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated and their votes allocated to their voters’ second-place choices, and so on until a candidate receives a majority of the votes.

RCV is increasingly employed in municipal and state elections around the country because the method has many advantages. It avoids costly runoff elections and assures that a candidate has significant support among a majority of voters. With the city providing an 8-1 match for certain campaign funds, hundreds of candidates are competing in City Council primaries and special elections this coming year. In a crowded race, absent RCV, a special interest-backed City Council candidate could win with less than 10% of the vote and without truly representing the interests of district residents.

At a time when our city faces daunting financial, social equity, policing, and economic recovery challenges, we can ill afford to have elected officials who do not broadly reflect the sentiments of their constituents. We need city-wide, borough-wide, and City Council representatives who can work together to heal the city as we come out of this destructive pandemic that has wreaked disproportionate havoc on our most vulnerable residents, small businesses, and much more.

Ranked-choice voting makes this possible. Candidates will not only have to appeal to their core voters, but also to a larger audience in order to attract second, third, fourth, and fifth preferences because, in a large field, no candidate is likely to garner 50% of the first-choice votes. Not only will this produce more civilized and democratic campaigns, but may also produce better ideas that can inform city governance beginning in 2022.

And, yet, some are now belatedly seeking to overturn or delay RCV. Are they motivated by the public or their own self-interest? Some opponents argue that voters of color won’t understand RCV and will leave their second through fifth choices blank. Huh? Most studies have shown that RCV actually benefits candidates of color. In San Francisco, which just recently implemented the system, London Breed, a Black woman, was elected Mayor, thanks in part to RCV.

Others say that the New York City Board of Elections is not prepared to implement the system, despite assurances otherwise from the Board’s Executive Director. There are now reports that county political party organizations, which appoint the BOE’s Commissioners, are attempting to put pressure on their appointees to get the Board to propose a delay. And, there has been an attempt to get the City Council to somehow reverse the recently-approved City Charter change incorporating RCV based on public approval last year. Some opponents have sought relief from the courts. The State Supreme Court recently denied a request for a restraining order to prevent RCV from being implemented in the special election to be held on February 2 in Queens for a City Council seat, which will be RCV’s first implementation in New York City.

Do these audacious, last-minute efforts to overturn the will of the voters sound somewhat like what we are seeing coming out of the White House?

Sadly, as with Donald Trump, these efforts are not expected to abate. However, as Justice Louis Brandeis said, “sunlight is the best disinfectant.” If the public fully understands the mechanics of ranked-choice voting and its advantages, it will be effectively implemented. The responsibility for educating the public rests with the city’s Campaign Finance Board, which says it is fully prepared to launch an education campaign. With the first Special Election scheduled in six weeks, a major educational campaign is already underway in that district, thanks to the efforts of Common Cause NY.

With two more special City Council elections coming in March and others to follow, the time to launch a citywide campaign is now. Civic organizations should augment the public education effort with their own campaigns, as they did with the successful effort to get New Yorkers to participate in the 2020 Census.

The main event will come in June when we will have primary elections for all city-wide, borough-wide, and City Council races. By then voters should be fully knowledgeable as to how the new system works and we are confident that it will lead to more democratic and healthy campaigns, more pleased voters and empowered elected officials, and a new city government that can work together for the benefit of all its residents.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from through 2008 through 2018, held a number of other roles in and out of government, and is now a columnist for Gotham Gazette. Carl Weisbrod has held many roles in and out of city government, was a member of the 2019 New York City Charter Revision Commission, and is now a senior advisor at HR&A.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How Blockchain Technology Can Boost Voter Confidence in New York City and Beyond

Voters on line for early voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Blockchain – many know it is a technology of the moment, but few understand how it works. It’s just one of those things that sounds important, but so many eyes glaze over when the phrase is used. But more and more, the use of blockchain technology is becoming commonplace, and it’s time we consider using it to make sure elections are as secure as possible.

First, the basics.

Blockchain is known as a “decentralized ledger” -- meaning that whenever a change is made to any digital information it contains, the change is recorded in multiple locations with a time and date stamp. These locations are known as “nodes.” So, it would be next to impossible for someone to simultaneously change any information in all the nodes without detection. That information is incredibly secure.

First used in cryptocurrency, blockchain’s use has expanded in recent years, to facilitate contracts, track supply chains, and conduct business virtually. But its potential in elections is especially exciting.

There are already some examples of blockchain at work in our democratic process. A handful of states have tested mobile application-based blockchain voting, including in the recent national elections. For example, voters in one Utah County had the option to use it to vote; this was so successful that the Utah State Legislature has introduced a bill to allow voting via blockchain in off-year municipal elections as well.

West Virginia also allowed members of the military and Americans overseas to cast their votes via a blockchain-based platform in 2018. When we consider the impact this could have in New York State, it is especially intriguing. After all, the 2021 New York City municipal elections are on the horizon – off-year contests that historically attract relatively few voters.

Here is how blockchain voting would work: Voters would be issued a blockchain ID or unique token whose digital voting activity can be tracked and traced, as we said, up and down the highway of information and right back to the source (the blockchain ID is simply an ID, not something that can track your digital or physical movements). Registered voters and new voters could authenticate their blockchain ID through an easy-to-verify process, similar to what one does when signing digital contracts or acquiring a driver’s license.

Once a voter’s identity is confirmed and the blockchain ID is authenticated, a platform with an application attached to it would be sync’d, similar to what took place in Utah County and West Virginia. This could be done in-person at polling stations as well. Once the vote is submitted, the vote is immutable and locked in. Each “voter key” always follows that voter so election boards would know who that voter is -- and where the vote is coming from. Hacking is pretty much impossible.

To be clear: it would be voluntary. No voter would be forced to use this technology. Therefore, it can never be used as a way to disenfranchise voters by creating onerous standards for identification.

Other benefits to incorporating blockchain in voting include:

The results are instantaneous as the time-stamped votes are tallied right away. This helps ensure voter and others know who their leaders are, avoiding the lag time we saw in some races, including New York.

It promotes social distancing in a way that early voting could not as people waited hours to vote in long lines less than six feet apart.

Mobile voting will become the norm for the next generation, already adept at using phones to conduct many daily tasks.

It promotes voter equity. Nearly everyone has a mobile phone, a tablet, an electronic device, or at a minimum access to a wireless hotspot that ensures virtually everyone of all backgrounds has access to the polls, including voters from lower-income neighborhoods, voters stationed overseas, or voters with disabilities. The more ways citizens have to vote securely, the better.

It creates cost efficiencies over time through reduced costs of running elections, including the time saved in faster and more accurate results that could reduce the days of counting votes and need for recounts.

While we should not go from zero to 60 when it comes to blockchain-based voting, we should continue to gradually incorporate its use and build upon its successes to-date. In the future, blockchain voting should be “on the ballot.”

***

Chao Cheng-Shorland and Allen Alishahi are co-founders of the blockchain startups ShelterZoom & DocuWalk.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Bidding on the South Bronx

A busy Bronx street (photo: Ruben Diaz Jr/Flickr)

A recent New York Times editorial entitled “Save New York’s Small Business” strongly encourages the city to become more small business-friendly and “go big.” I would suggest that when it comes to saving our small businesses and neighborhoods, often it is not the big that is needed – it is the go part. Getting stuff done in improving neighborhoods can be very challenging.

From Flatbush Avenue to Fordham Road, Business Improvement Districts (BID) have become a very effective and powerful tool in engaging property owners and merchants to fund street cleaning, public safety, and marketing of the city’s retail corridors.

They were created in the ‘80s when retail corridors across New York City struggled with crime, grime, and disinvestment. BIDs grew in popularity through the ‘80s and ‘90s as an effective way to create cleaner, safer, and more vibrant neighborhoods.

Towards the end of his second term, Mayor Giuliani curbed the growth of BIDs, fearing they were becoming too powerful a tool for neighborhood enhancements – and outside his control.

In developing a blueprint for recovery after September 11, 2001, Mike Bloomberg understood that BIDs successfully harnessed private sector creativity and forged effective public-private partnerships for the purpose of neighborhood improvement. He quickly restored the city’s alliance with BIDs. During the Bloomberg years, BIDs grew from 44 to 70 with an emphasis on the smaller corridors outside of Manhattan.

During my 12 years as commissioner of the Department of Small Business Services, I saw the impact BIDs had on bringing community leaders around the table to solve problems with government. We cheered them on, challenged them to be more creative and impactful, and recognized achievements. When a BID was failing, we worked with property owners to make the necessary changes in leadership.

Fast forward. Today, there are 76 BIDS across the city and they invest $167 million in supplemental services for our neighborhoods. In the thick of this pandemic, these services have become even more important in stabilizing our neighborhoods and keeping the doors open of many of our mom-and-pop shops.

During a time when many of our small businesses are struggling to stay afloat, the city has taken a meat cleaver to the Department of Sanitation’s budget. One would think that the leadership at City Hall would be embracing an all hands-on deck approach — making an extra effort in encouraging more neighborhoods to create vibrant, clean, and safe districts.

I recently had the opportunity to walk the Mott Haven neighborhood of the Bronx with community leader and local resident Michael Brady. I saw how the once-thriving piano manufacturing district is undergoing an impressive renaissance. Restaurants and other small businesses have opened, with more coming. A new school is being built. The old piano factories have a new life as homes and hundreds of apartments are being added where empty lots existed for decades.

Along my walk, I met a number of merchants who are fully engaged in making the neighborhood a better place. I also noticed pockets of illegal dumping, overflowing trash cans, and graffiti. With such an engaged group and new developments on the horizon, the formation of a Business Improvement District seems to me like a no-brainer to add an extra shine to this neighborhood. As I listened to their creative ideas and saw some of the problems, I thought about my own experience more than two decades ago leading a BID in the revitalization efforts along 14th Street and Union Square.

And here we come back to my point that often it is not the ‘big’ that is needed but the ‘go.’ Sadly, in Mott Haven, city government discouraged efforts to create a BID for this growing retail corridor and has not actively encouraged the creation of a BID.*

The foundation of any smart economic development strategy begins with a laser focus on quality-of-life issues. In this South Bronx neighborhood, there is an engaged group of leaders eager to take on the dirty streets and empty storefronts that are eyesores in the community.

Plain and simple, it makes no sense at all, especially during a time of this crisis, to deny these merchants the ability to create a BID. Small Business Services should work with the community board and the City Council to get this moving.

The city needs to double-down on public-private partnerships – not be a barrier to them. Let’s go!

*In response to this column, the Department of Small Business Services sent the following statement, which is in part disputed by conversations with the aforementioned Michael Brady, who has reiterated that he was actively discouraged from starting a Mott Haven BID and since 2017 has helped lead other efforts in the area instead:

"SBS has not been approached by a merchant organization seeking to form a BID in Mott Haven since 2017. At that time, we provided guidance on the City’s BID formation process and necessary next steps. We continue to support community-based organizations across the City when they seek to create BIDs and as they build thriving neighborhoods. For more information about the process of BID formation, please visit nyc.gov/bid"

Note: based on SBS' apparent willingness to work on a Mott Haven bid with local leaders, where this column originally stated "Sadly, in Mott Haven, city government continues to block efforts to create a BID for this growing retail corridor." It now says that city government discouraged efforts to create such a BID.

***

Rob Walsh oversaw the city’s Business Improvement District program in his role as the Commissioner of the Department of Small Business Services from 2002 through 2013. He served as the Executive Director of the Union Square Partnership — the city’s first Business Improvement District — from 1989 to 2007.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Must End Solitary Confinement in New York

We need to end solitary confinement in our city and state. Spending all day in a cell the size of an elevator can cause permanent brain damage. Common sense tells us this. Science confirms it. But only the words of someone who has been in solitary confinement can begin to explain it.

“No one to talk to. Nothing to do. I did push-ups. I read the Bible. That’s it. For days.” That is the way my brother-in-law explained it to me. And the haunting look in his eyes –– years later –– conveyed more than words ever could.

This is an issue of fundamental human rights. The United Nations General Assembly, through the adoption of the Nelson Mandela Rules, has denounced the use of solitary confinement for any period exceeding 15 days. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture raised banning solitary confinement altogether for persons detained pretrial. However, prisons and jails in New York State hold people in solitary confinement for years, and our city jails routinely use solitary confinement in pretrial detention.

This is also a racial justice issue. Black people represent about 18% of the state population, 43% of those incarcerated in the state, and 57% of those held in solitary confinement. In New York City, of the jailed patients receiving mental health services, Black and Latino patients were 2.52 and 1.65 times more likely to be put in solitary confinement than white patients.

The harm is undeniable. Hypersensitivity to stimuli. Hallucinations. Increased anxiety. Diminished impulse control. Severe and chronic depression. Nightmares. Self-mutilation. Difficulties with concentration and memory. These effects last well beyond solitary confinement and incarceration. Those who have spent time in solitary confinement are more likely to die upon release from custody, either by homicide or suicide, and are more likely to be reincarcerated.

The specter of solitary confinement looms large in jails and prisons. Contrary to popular perception, solitary confinement is not reserved for persons convicted of the most violent offenses or those who put staff and others in custody in danger.

Take, for example, my brother-in-law. He was in a schoolyard fight as a college student. One of his friends had a gun. Everyone in the fight was prosecuted. My brother-in-law was incarcerated for a gun he never touched and did not know about. He then was put in solitary confinement when he stood up for himself after someone twice his age took his dinner and dared him to say something.

Also contrary to public opinion, solitary confinement does not make prisons or jails safer. Research supports common sense here too, finding that the psychological damage caused by solitary can cause those placed there to act more violently. Other jurisdictions have shown that reducing solitary confinement can reduce jail violence. Cook County in Illinois banned solitary confinement in 2016 and found that assaults on people in custody and staff plummeted to an all-time low.

Lawsuits can help. I was the Chief Deputy at the New York Attorney General’s Office, and we sued a private contractor that provided medical services for a county jail. On the contractor’s watch, five people died due to inadequate medical care. Two others died, in solitary confinement, in another jail overseen in the state by this contractor. Our lawsuit got the contractor barred from providing jail health services in New York for three years.

But, the best and clearest solution is for the State Legislature and the City Council to act. Right now, the state prison system uses solitary confinement with impunity, handing out lengthy and virtually unlimited sentences for even minor infractions. The HALT Solitary Confinement Act would go a long way towards reducing its overuse, prohibiting anyone from being held in solitary confinement for more than 15 days and limiting its application to the most egregious conduct.

New York City has limited solitary confinement to serious infractions and capped its use at 30 days. But, the city’s Department of Correction has dodged these requirements by putting some people in a so-called “restraint desk,” where persons in custody have both legs and one arm strapped to a desk during their “out of cell time.”

Both the city and state must go further. We must ban the use of solitary confinement altogether -- as well as these “restraint desks” or any other method that results in banning solitary in name only.

I think often of my brother-in-law, in solitary confinement, doing push-ups and reading the Bible. The horrors of solitary confinement violate standards of human dignity. One need not be of a particular faith or religion to see this. But, this week after Christmas, let those of us of the Christian faith not view the Bible only as a text that may give comfort to those in solitary confinement and otherwise marginalized by society. Let us also recall Jesus’ clear direction to the rest of us to care for and speak up for those in prison.

***

Alvin Bragg is Co-Director of the Racial Justice Project at New York Law School, former Chief Deputy Attorney General of New York State, and a candidate for Manhattan District Attorney. On Twitter @AlvinBraggNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

More Covid Special Elections are Coming; Let’s Make Them as Safe as Possible

Voting during a pandemic (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Governor Cuomo just shut down indoor dining in New York City for the second time this year. Hospitalization rates and COVID-19 positivity rates across the five boroughs continue to soar, and the Mayor is warning that a full shutdown is imminent.

Earlier this month, Dr. Anthony Fauci announced that "we could start to see things start to get really bad in the middle of January, not only for New York state but for any state or city." Amid this dire backdrop, the City’s Board of Elections is holding a special election in Council District 12 in the northeast Bronx, where voting has already begun, and is also preparing for four other City Council special elections, to take place in the coming months. Two Queens elections are already scheduled for February, and two Bronx elections, including my race in District 11 in the northwest Bronx, will likely be scheduled for March.

In light of what the City faces, we need to make sure to prioritize public health and our fight against this virus, while guaranteeing that all New Yorkers have full representation on the City Council as soon as is safely possible. Here are some proposals to make sure the four upcoming City Council races do not set us back in our fight against the coronavirus.

Suspend Requirement Candidates Collect Voter Signatures to Appear on Ballot

In normal circumstances, candidates running in a special election for City Council are required to file petitions with 450 signatures of registered voters in their district in order to appear on the ballot. In reality, election lawyers encourage candidates to collect three times that number -- 1350 -- in case the petitions are challenged in court.

While petitioning for the Queens races has already taken place, petitioning can and should be suspended for the upcoming Bronx races. To require what could be more than a dozen candidates in these two races to travel their communities to come in close contact with thousands of people at this time is highly irresponsible and could result in more people contracting this virus. As an alternative, candidates who have qualified for the Campaign Finance Board’s matching program, which requires City Council candidates to receive a minimum of 75 in-district donations of $10 or more, should be allowed to appear on the ballot.

Send Postage-Paid Absentee Ballots to All Eligible Voters

For any election, voters should have as many options to cast their votes as possible. For these upcoming elections, this must include every effort to encourage people to vote by mail. If every eligible voter has an absentee ballot sent directly to their home, more will vote by mail. Period.

Postpone In-Person Voting Until More People Have Been Vaccinated

The City Charter requires the Mayor to call special elections within 80 days of a City Council Member leaving office. But while the Mayor is obligated to schedule these elections, the Governor can postpone them, as he has done with other elections this year to help to slow the virus’ spread.

The expansion of mail-in balloting in New York has reduced the number of people physically at the polls, but many will still vote in person, either out of preference, or because they do not receive a ballot by mail, or because they require assistance.

With vaccines now being deployed, a postponement of in-person voting for these four elections to April or May could make a tremendous difference -- for poll workers, for voters, and for their families. With the state prioritizing vaccine distribution to New Yorkers above the age of 65 and to those with underlying health conditions, even a modest delay could mean thousands of our most vulnerable neighbors would be more protected before exercising their right to vote.

***

Abigail Martin is a social worker and an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work, and a candidate for City Council in District 11 in the Bronx. On Twitter @Abigail4theBX.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

For Schools, Communities and Families to Recover from Covid, We Need More Women in Leadership

The men making schools decisions (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

School reopening has been a particular challenge for women in New York City. From lack of communication between the Department of Education, staff, and caregivers, constantly changing schedules, failure to invest in a care economy that values domestic labor and childcare, lack of tech support, and lack of funding to the daily demands of remote learning and the material conditions in schools, women have been hit hardest by the struggles our schools face.

As we think about how our city and school system can begin to recover from this ongoing crisis, one thing is clear: We need to both elect more women and systematically encourage women to lead.

As an early childhood elementary school teacher and an organizer and candidate, we’ve seen first hand how women in school communities have been disproportionately burdened with adapting to schooling during the pandemic. This disproportionate burden isn’t new, but COVID-19 has exacerbated gender inequities in schools, the home, and other workplaces.

It's no coincidence that the people making decisions about schools in New York City are men, and mostly white men: Governor Cuomo, Mayor de Blasio, schools chancellor Carranza, principals union Cannizzaro, and teachers union president Mulgrew have largely determined every aspect of the city’s school reopening plan.

Yet the vast majority of school-based workers — teachers, social workers, service providers, cafeteria staff, paraprofessionals, guidance counselors, nurses — are women. These stakeholders have been consistently excluded from decision-making, even as they are being asked to nurture children with inadequate support amid a deadly pandemic and during a traumatic, unjust, emotional rollercoaster.

The Department of Education surveyed employees just once during the last nine months, and United Federation of Teachers (UFT) leadership has not solicited systematic input from members at all. Because the majority of school workers are women, many are teaching or providing services while also caring full-time for their own children and dependent loved ones at home. Many school-based staff have also taken on brand new roles this year with little support, requiring countless hours of unpaid overtime, in stark contrast to city workers in unions dominated by men like the NYPD, where there is no such thing as working without pay.

Likewise, the burden of childcare and navigating hybrid and remote learning has largely fallen on women across the city, exacerbating already existing gaps. Mothers, aunts, and grandmothers are largely the ones supporting their children with remote learning while still balancing work and other responsibilities. This burden has fallen most on Black and/or immigrant families whose children are in remote cohorts at higher rates than white families, whose communities have been hit hardest by COVID-19, and who often have to overcome language barriers with little support from the Department of Education. Inexcusably, the mayor has had no plan to make remote learning better or more accessible to fully-remote families, despite widespread criticism. In the face of increasing agitation from parents and educators, the mayor and the chancellor only recently announced the framework of a new plan.

To make matters worse, many working women who are also caretakers tasked with supporting children through remote and hybrid learning have been relegated to an inequitable and indefinite hardship by the burdens of unemployment or workplace protections that don’t prioritize a care-based economy.

Our city’s COVID-19 recovery urgently requires a legislative agenda that recognizes women’s paid and unpaid work — during this pandemic and beyond — as worthy. Our city must close the gender wage gap; adequately fund childcare and childcare providers; divest from policing and fully fund our public schools so that every school has at least one nurse, counselor, and social worker; compensate family-based and early childcare educators; proactively solicit input from educators, school-based staff, and parents about school reopening, remote learning, and in-person learning on a regular basis; give all educators ample additional planning and collaboration time whether they are remote or in-person; and invest in CUNY campus childcare.

We imagine a city where decisions are made centered on care, in its fullest form, where parents and school staff are at the table and their voices are heard, where the labor of caregivers — whether teachers, parents, service-providers or health workers — is celebrated, funded, loved, and valued.

As we approach the 2021 elections in New York City, we have an opportunity to prioritize childcare, education, and gender equity to ensure our recovery from covid doesn’t leave women even further behind. To do so, we can start by making sure our leaders understand the disproportionate impact this pandemic has had on women. It’s high time we elect more compassionate, bold women who have been doing the work of caring for communities.

***

Shahana Hanif is an organizer and candidate for City Council in District 39 in Brooklyn. Liat Olenick is a public school teacher, advocate, and activist leader. On Twitter @ShahanaFromBK & @Liat_RO.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York and the Veto–Proof Legislature

Governors Andrew and Mario Cuomo (photo: governor's office)

Early in 1984 I visited Governor Mario Cuomo’s office in Albany at his invitation. He wanted to discuss a talk I’d given at the New School about his first year as governor. I found myself going on about the growing dominance of the governor in New York’s legislative process. Governor Cuomo loved to debate. I knew from earlier experience that trouble was ahead when he started a sentence by addressing me as “professor.”

“Don’t you realize, professor,” he said, “that when it comes to making law, they can act without me, but I cannot act without them?” His point was that he could block passage of a law, but that a determined legislature, by a two-thirds vote of those elected to each house, could override his veto.

Fast forward to the 2020 election. It resulted in “veto-proof majorities” – one party with more than two-thirds the seats – in both the Assembly and the Senate. This has not occurred in New York since 1948, and was a first for the Democratic Party in the legislature since the adoption of the state’s current constitution in 1894. It has generated considerable discussion about the prospect of the legislature using the override power to enact a more progressive policy agenda than favored by Mario Cuomo’s son, the current governor, Andrew Cuomo. How realistic is that conjecture?

The Rules and Their Consequences

All state constitutions provide for an executive veto; all also provide for legislative override. In New York, the executive veto power was added to the state Constitution at the 1821 constitutional convention. (Previously the veto resided in a Council of Revision. That Council might be overridden by two-thirds majorities of both houses; this possibility was carried over to apply to the new governor’s veto.)

Compared to provisions in other states, New York’s legislative majorities required to override a governor’s veto are both the most typical and the most demanding. In 36 states the majorities needed in each house to override the governor are the same as in New York. In six – and in unicameral Nebraska – it’s three-fifths. In six it’s a simple majority. Unique to Alaska, two-thirds of the members of both houses meeting jointly are required to override.

Nationally, state legislatures seek to override about one in 20 gubernatorial vetoes. But in New York, override attempts are very rare. The two-thirds vote required in each house is a high bar. Also, the relative strength of the governor’s overall powers discourages taking on the executive. For much of the 20th Century, a constitutionally-based gerrymander usually produced Republican majorities in the Assembly and Senate. Until fairly recently, however, the state’s history of political competitiveness kept one party or the other from overwhelming dominance within each house. Thus, from the governorship of Democrat James T. Hoffman in 1872 until that of Democrat Hugh Carey in 1976 – a period of 104 years – New York governors used the veto freely, but none was overridden.

The History in New York

In the 19th Century all city charters were state laws; they therefore could only be adopted and amended by the state legislature. The legislature in 1872 overrode Governor Hoffman’s veto of a charter amendment concerning the structure and accountability of the proposed elected City of Albany Police Commission favored by the leaders of both major parties.

Over a century later, in 1976, during the second year of the Carey administration, the override arose from political pressures connected with a massive New York City fiscal crisis. In response to draconian New York City budgets the teachers union sought a state legislative mandate that total New York City education spending not fall below the average spent for this purpose in the three previous years. Governor Carey vetoed the bill; he said he did so to assure equity in the distribution of the inevitable pain that the city’s fiscal crisis was producing. The legislature overrode the veto.

The lower courts found unconstitutional the process by which the veto was undone in the Senate. However, the state’s high court, the Court of Appeals, disagreed. In performing their duty as the final arbiters of what the constitution means, Judge Jones wrote for the majority, judicial review may be undertaken to determine whether the legislature has complied with constitutional prescriptions as to legislative procedures. But, he said, in deference to a coequal branch, “… [in general the courts will not interfere with the internal procedural aspects of the legislative process…]"

The six successful overrides since then focused upon financial issues, such as state spending, mandates upon New York City, and local taxation.

Governor Carey was often dismissive of the legislature. Moreover, under Speaker Stanley Fink, the Assembly became more assertive in independently advancing a policy agenda. Also, as austerity eased later in Carey’s second term the legislative houses, restive with gubernatorial dominance of revenue-estimating, each developed an independent capacity to project how much more money there was to spend, and set out to spend it. In 1979 the Assembly overrode Carey’s vetoes of Assembly initiatives, backed by the Senate, to ease the impact on working poor and older New Yorkers of heating price increases arising as a result of the energy crisis. In 1982 many of Carey’s numerous vetoes of legislative budget adds were overridden. Also, in that year the legislature overrode the governor’s veto of a bill passed to circumvent a politically-explosive state high court decision requiring full value assessment of real estate for tax purposes.

In his 12 years in office beginning in 1982, Mario Cuomo himself had not a single veto undone by the legislature. His successor George Pataki, a Republican, was overridden three times. In 1996 he failed in an attempt to block a measure favored by the New York City Police Benevolent Association that the city’s Republican mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, claimed would result in $200 million in additional labor costs. In 2003 the legislature overrode Pataki’s vetoes of several state and New York City tax bills, most importantly the first state increase in the personal income tax rate in over two decades. And in 2006, the Senate and Assembly overrode almost all of Pataki’s vetoes of their budget additions.

Since then, there have been attempts, but no veto overrides passed by both houses of the New York legislature. Democratic Governor David Patterson’s 2010 veto of an ethics reform bill was overridden in the Democratic Assembly, but not in the Republican Senate. In 2018 Governor Andrew Cuomo’s veto of a bill that sought to fund full-day kindergarten in the remaining nine New York school districts that had not instituted it, was overridden unanimously by bipartisan vote in the Republican-run Senate. However, in the Democratic Assembly, where the bill had also initially passed unanimously with bipartisan backing, Speaker Carl Heastie declined to follow suit.

The Intra-Party Dilemma

Democrats have controlled the New York State Assembly since 1974. Since 2002, except for 2010 and 2011, they have held more than 100 seats in that 150-seat body, a veto-proof majority. Republicans commanded a Senate majority from 1969 through 2008 and 2010 through 2018, but never held two-thirds or more of the seats.

Without a veto-proof majority, overriding a gubernatorial veto requires support from a chamber’s minority party members. In the highly-partisan New York legislature, majorities rarely see value in empowering the opposition. Moreover, minority party members in a house may be in the governor’s party, sharing the governor’s views and responsive to the governor’s appeal on partisan grounds.

Most significantly, however, overriding the governor in this circumstance of divided partisan control requires majority party legislators in one house to take on a chief executive of their own party, daunting and risky for members who might later be dependent on gubernatorial support or good will for realization of their ambitions. History shows that each override effort in the state has been variously motivated in the specific circumstance by the convergence of a different mix of factors, including for example: a desire to assert the power of the legislative institution; a need to please a valued constituency; and/or a wish to publicly embarrass or sanction the governor, the mayor of New York City, or another political adversary.

Notwithstanding its rarity until now, experience elsewhere suggests that more frequent override politics might well be in store for New York with the arrival of Assembly and Senate veto-proof majorities. In 2021, according to Ballotpedia, “…there were 22 state legislatures where one party held a veto-proof majority in both legislative chambers.” (Unicameral Nebraska also had such a majority in its Senate, though it is formally non-partisan.) Analogous to the coming situation in Albany, most of these legislatures were controlled by the majorities of the governor’s party.

Yet co-partisanship did not preclude veto overrides, most focused on fiscal issues. For example, in Mississippi in 2020 the Republican legislature overrode a partial veto by Republican Governor Trent Reeves of an education appropriation bill linked to teacher pay. And in Oklahoma the Republican legislature overrode Republican Governor Kevin Stitt’s veto of the state budget as excessively draconian. In both of these states overriding the governor’s veto requires a two-thirds majority in each house, just as it does in New York.

A busy 2021 legislative session is in the offing in Albany. In the still early days of a long dark COVID-19 winter, the Senate and Assembly will likely continue meeting remotely. Early on, legislators will have to decide whether to continue the governor’s pandemic-related emergency powers, initially limited to a year. The mix of spending cuts and taxes to address the state and local fiscal crisis will dominate the agenda. Unless delayed by the unavailability of Census data, majority members will be focused upon adopting redistricting plans that assure job security for themselves and further entrench Democratic control of both houses. Democrats will almost surely also try to grow their share of the (shrinking) state Congressional delegation.

Proposed changes to the state constitution, a process in which the governor has no formal role, offer opportunities for legislative assertion without the need to override. Legislators will consider first-passage of a constitutional amendment to ask the people to help them regain some of their greatly diminished fiscal powers. There is also an unfinished ballot-access, election-reform agenda. Having been given a taste of the convenience of no-excuse absentee voting, constituents will expect its continuance. This will require second passage of a constitutional amendment. An amendment will also be needed to reform New York’s party-dominated process for election administration, which again proved very problematic this year.

Newly-elected progressive Democrats see veto-proof majorities as a tool for wresting control of the policy agenda from the governor to institute their social change agenda in such areas as health care, criminal justice reform, and tenants’ rights. They are likely to be disappointed.

As noted, there is a lot to do in the coming session, in a difficult environment. Second, just look at the state’s map of the presidential vote in 2020. Much of the territory outside the big cities is red, including in some New York City suburbs. Democratic legislators elected from these areas are moderate, even conservative. They do not necessarily embrace a full progressive agenda. Moreover, Governor Andrew Cuomo is of their own party, remains very powerful, and intends to seek a fourth term. Also, Cuomo’s status was elevated as he became the alternative Democratic voice to President Donald Trump’s in addressing the pandemic. He retains a national platform that has a multiplier effect: it is a political and governmental resource within the state. And in recent months, as the state’s Democratic Party has re-centered to the left, the governor has found a way to visibly move with it, for example on the question of police reform.

But then there is the budget.

New York is looking at a $14.9 billion shortfall for fiscal year 2021 and a total revenue gap of $63 billion through fiscal year 2024. Federal aid to states and localities has still not been appropriated. The governor has publicly said that the state will need to raise new taxes. But almost certainly he will seek to fill the gap with far more cuts than new revenue, while most Democratic legislators will prefer the opposite. Moreover, taxing the rich more heavily, advocated by progressive Democrats, might be preferable to their less liberal colleagues than higher property taxes or major layoffs in school districts and municipalities. So this is where the Democratic legislative intra-party unity required for veto override politics may emerge. And, as Governor Andrew Cuomo’s father taught me, “they” might very well make law without him.

***

Gerald Benjamin is Emeritus Founding Director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Note: this column has been updated with two additional veto overrides not included when the piece first published.

This column has also been updated to reflect the full details of the legislative override of Cary in 1976.

New York City Schools and The Myth of Meritocracy

Mayor de Blasio at a schools announcement (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayor's Office)

When I was younger, my grandfather - an asylum seeker - used to tell me that hard work and persistence will always be rewarded. After all, he became successful in the United States after years of injustice in Egypt. And so, I believed him.

But during my time in high school, I have learned that this idea of hard work amounting to success is not the case in the New York City public school system.

Right before I was born, my family moved into a tiny downtown apartment specifically so I could attend a District 2 public school. Schools in my district have PTAs filled with eager and economically advantaged parents. These schools provide powerful support networks, internship opportunities, extracurriculars galore, and experienced teachers. At my elementary school, my classmates and I stood in circles, held hands, and sang John Lennon paeans to a harmonious and peaceful world. I had yet to learn that this dream was only a guarantee for children coming of age in certain New York City zip codes.

Last year, I served as the student representative on the Community Education Council for District 2, and there we held a forum on school admissions screens. For decades, screens (attendance, zip code, grades, and more) have become a leading cause of school segregation at the high school level in New York City. At this forum, one parent after another spoke about how their children simply needed screens; they needed the gifted-and-talented programs and all the other methods of distinction in order for their children to flourish. The truth is that students of all backgrounds are motivated to excel at school and in life. However, only a portion of our city’s students can excel in this public school system — a system that self-identifies as a meritocracy but is clearly slanted towards the privileged.

Last week, principals of three screened District 2 high schools — Eleanor Roosevelt, NYC Lab, and Baruch — issued statements calling for an end to one of the most harmful screening mechanisms: a geographic preference for students (like me) who live in District 2. Ending District 2 priority is an important step towards integration.

Earlier this year, Teens Take Charge, a student-led education advocacy group where I am an organizer, submitted multiple Freedom of Information requests to the New York City Department of Education (DOE), requesting the demographic breakdown of applicants and offers to each public high school. After four months of delays, the DOE finally shared some of the data with us. It was striking.

Last year, at my District 2 school, The Clinton School, two-thirds of offers went to white students, 12% went to Hispanic students, and just 4% went to Black students. At the aforementioned schools whose principals have started speaking out — Baruch, NYC Lab, and Eleanor Roosevelt — disparities were even greater. Black and Hispanic students combined for less than 10% of offers to each school, even as these groups account for nearly 70% of public school students in the city.

It’s not simply a few schools that have admissions flaws. The issue is systemic, and this hyper-segregation has been normalized.

Amidst a global pandemic, existing racial and economic inequities have only grown worse. Access to resources — computers, WiFi, even a quiet space — has become scarce for many students in lower-income communities and students who live in temporary housing. At a recent meeting on the topic of students in temporary housing, the District 2 CEC attempted to confront these issues.

Our CEC has been trying to increase broadband WiFi and distribute noise-cancelling headphones to students in temporary housing in our district. But as CEC member Shino Tanikawa stated, “We are not solving the problem of homelessness. We are putting on a Band-Aid.” Even with Band-Aid efforts to support vulnerable students and families, there is no way that an admissions system that was discriminatory before the pandemic will be fair to these students now.

Finally, the city took some baby steps in the right direction on Friday. Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza announced that all middle schools will be unscreened for the upcoming school year (2021-2022). In addition, District 2 geographic priority will also be removed, so that students from all districts will have the opportunity to get accepted into one of District 2’s highly selective schools. It’s saddening that it took a pandemic for these systematic changes to finally happen, but this is a first step forward on the road to ending discriminatory screens in New York City public education. The admissions system that was discriminatory before the pandemic has met its moment during this crisis, and we must push for structural changes after it’s over.

Mayor de Blasio’s and Chancellor Carranza’s actions are far from sufficient on the high school level, as discriminatory screens (testing, grades, attendance, etc.) still remain distinguishing factors during the admissions process. In addition, rather than looking at 7th grade test scores, high schools will now consider 6th grade scores (we are talking about 11-year-olds here). The truth is that principals of screened high schools have the autonomy to unscreen their schools, and unless they take action, the freshmen entering in fall 2021 may be one of the most segregated classes in history.

At a recent meeting with Chancellor Carranza and Adrienne Austin, Acting Deputy Chancellor of the DOE, both noted that these recent actions are not a solution, but a step forward. They cannot yet answer the question of whether these policies will extend beyond the COVID-19 era. My school — with its PTAs, state-of-the-art library, test books, faculty — is one of the most well-resourced in the city. We must ensure that the students who can most benefit from these resources have access to them.

Right now in New York City, six decades after Brown v. Board of Education, we are only beginning to carve a path towards equity and integration. We don’t know how the actions we saw on Friday will play out in the long run. But, the pandemic put a spotlight on festering inequities, and this is the moment to finally enact system-wide changes. It takes imagination and the will to make some strategic changes to our current system. We can build a more equitable educational system that lifts all students and creates a stronger, more equitable New York City.

***

Violet Becker is 17 years old, a senior at The Clinton School, an organizer with Teens Take Charge, and former student representative of the Community Education Council for District 2. On Twitter @TeensTakeCharge.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This Holiday Season, Mental Health Support is Here for New Yorkers

Mental health care workers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

The holidays can be an emotionally-charged time and bring up mixed feelings that may include stress, grief, and loneliness and also feelings of joy, gratitude, and hope for the new year, sometimes all at the same time.

But this year is filled with new challenges — so many New Yorkers have experienced significant losses and will celebrate the holidays differently than in past years. Health care providers and other essential workers have been on the front lines of a global crisis. All of us are dealing with the tremendous stress and uncertainty of this moment.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, large numbers of New Yorkers have turned to the city’s mental health hotline, NYC Well, for mental health support. NYC Well's counselors and peer support specialists have fielded more than 200,000 calls, texts, and chats since April, and there are no signs of the need slowing down. In the last two months, NYC Well has responded to more than one-and-a-half times the calls, texts, and chats than the same period last year.

A recent independent evaluation found that people reflecting a diverse range of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education use the helpline’s services. Of the New Yorkers contacting NYC Well during the evaluation period, 36% identified as white, 30% as Black or African-American, 8% as Asian, and 8% indicated multiple races. In a separate question, 26% identified as Latino or Hispanic.

The reasons New Yorkers contact NYC Well vary as greatly as New Yorkers themselves. Some have reached out in a moment of crisis, or to receive a referral for therapy at a clinic that accepts their insurance. Others have wanted tips on dealing with overwhelming stress and uncertainty. Some New Yorkers with mental health challenges use the service regularly to connect with peers with lived mental health experience for support in addition to other ways they manage their health. Many people reach out because they're worried about someone they know. In cases where urgent in-home intervention is needed, mobile crisis teams of behavioral health professionals can be dispatched to address the crisis and link the person to ongoing services.

This holiday season may look and feel different from past years and may bring new challenges. NYC Well is always just a phone call, text, or chat away. Call 888-NYC-WELL (888-692-9355), text “WELL” to 65173, or chat at nyc.gov/nycwell. NYC Well’s website also offers a number of wellbeing and emotional support applications (apps) that can help you cope.

You will be treated with respect and empathy. Your conversations will be kept confidential, and you can get help in the language you're comfortable. NYC Well offers translation services for over 200 languages.

There’s a reason why NYC Well has answered over a million calls, texts, and chats from New Yorkers: no matter who you are or what you’re dealing with, talking to someone can help. This holiday season, NYC Well is here for you.

***

Dr. Hillary Kunins is the Executive Deputy Commissioner of Mental Hygiene at the New York City Department of Health. Susan Herman is Director of the Mayor's Office of ThriveNYC. On Twitter @MentalHealthNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.