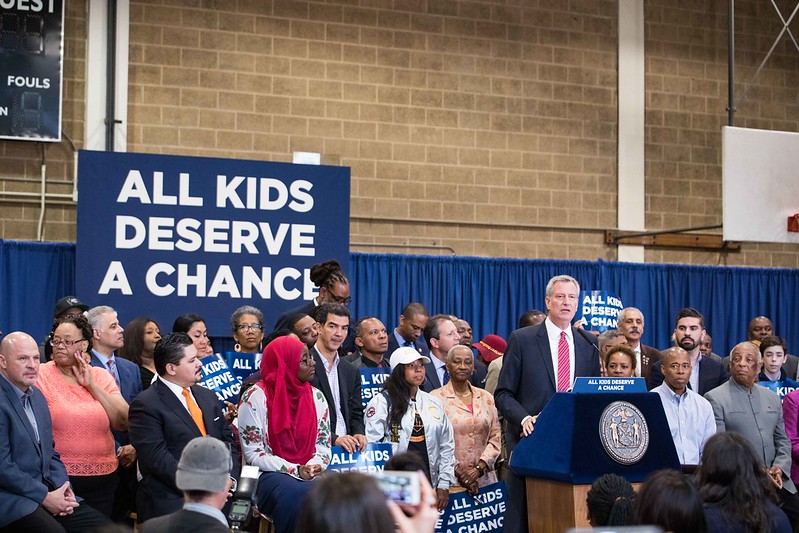

Mayor de Blasio at a schools announcement (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayor's Office)

When I was younger, my grandfather - an asylum seeker - used to tell me that hard work and persistence will always be rewarded. After all, he became successful in the United States after years of injustice in Egypt. And so, I believed him.

But during my time in high school, I have learned that this idea of hard work amounting to success is not the case in the New York City public school system.

Right before I was born, my family moved into a tiny downtown apartment specifically so I could attend a District 2 public school. Schools in my district have PTAs filled with eager and economically advantaged parents. These schools provide powerful support networks, internship opportunities, extracurriculars galore, and experienced teachers. At my elementary school, my classmates and I stood in circles, held hands, and sang John Lennon paeans to a harmonious and peaceful world. I had yet to learn that this dream was only a guarantee for children coming of age in certain New York City zip codes.

Last year, I served as the student representative on the Community Education Council for District 2, and there we held a forum on school admissions screens. For decades, screens (attendance, zip code, grades, and more) have become a leading cause of school segregation at the high school level in New York City. At this forum, one parent after another spoke about how their children simply needed screens; they needed the gifted-and-talented programs and all the other methods of distinction in order for their children to flourish. The truth is that students of all backgrounds are motivated to excel at school and in life. However, only a portion of our city’s students can excel in this public school system — a system that self-identifies as a meritocracy but is clearly slanted towards the privileged.

Last week, principals of three screened District 2 high schools — Eleanor Roosevelt, NYC Lab, and Baruch — issued statements calling for an end to one of the most harmful screening mechanisms: a geographic preference for students (like me) who live in District 2. Ending District 2 priority is an important step towards integration.

Earlier this year, Teens Take Charge, a student-led education advocacy group where I am an organizer, submitted multiple Freedom of Information requests to the New York City Department of Education (DOE), requesting the demographic breakdown of applicants and offers to each public high school. After four months of delays, the DOE finally shared some of the data with us. It was striking.

Last year, at my District 2 school, The Clinton School, two-thirds of offers went to white students, 12% went to Hispanic students, and just 4% went to Black students. At the aforementioned schools whose principals have started speaking out — Baruch, NYC Lab, and Eleanor Roosevelt — disparities were even greater. Black and Hispanic students combined for less than 10% of offers to each school, even as these groups account for nearly 70% of public school students in the city.

It’s not simply a few schools that have admissions flaws. The issue is systemic, and this hyper-segregation has been normalized.

Amidst a global pandemic, existing racial and economic inequities have only grown worse. Access to resources — computers, WiFi, even a quiet space — has become scarce for many students in lower-income communities and students who live in temporary housing. At a recent meeting on the topic of students in temporary housing, the District 2 CEC attempted to confront these issues.

Our CEC has been trying to increase broadband WiFi and distribute noise-cancelling headphones to students in temporary housing in our district. But as CEC member Shino Tanikawa stated, “We are not solving the problem of homelessness. We are putting on a Band-Aid.” Even with Band-Aid efforts to support vulnerable students and families, there is no way that an admissions system that was discriminatory before the pandemic will be fair to these students now.

Finally, the city took some baby steps in the right direction on Friday. Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza announced that all middle schools will be unscreened for the upcoming school year (2021-2022). In addition, District 2 geographic priority will also be removed, so that students from all districts will have the opportunity to get accepted into one of District 2’s highly selective schools. It’s saddening that it took a pandemic for these systematic changes to finally happen, but this is a first step forward on the road to ending discriminatory screens in New York City public education. The admissions system that was discriminatory before the pandemic has met its moment during this crisis, and we must push for structural changes after it’s over.

Mayor de Blasio’s and Chancellor Carranza’s actions are far from sufficient on the high school level, as discriminatory screens (testing, grades, attendance, etc.) still remain distinguishing factors during the admissions process. In addition, rather than looking at 7th grade test scores, high schools will now consider 6th grade scores (we are talking about 11-year-olds here). The truth is that principals of screened high schools have the autonomy to unscreen their schools, and unless they take action, the freshmen entering in fall 2021 may be one of the most segregated classes in history.

At a recent meeting with Chancellor Carranza and Adrienne Austin, Acting Deputy Chancellor of the DOE, both noted that these recent actions are not a solution, but a step forward. They cannot yet answer the question of whether these policies will extend beyond the COVID-19 era. My school — with its PTAs, state-of-the-art library, test books, faculty — is one of the most well-resourced in the city. We must ensure that the students who can most benefit from these resources have access to them.

Right now in New York City, six decades after Brown v. Board of Education, we are only beginning to carve a path towards equity and integration. We don’t know how the actions we saw on Friday will play out in the long run. But, the pandemic put a spotlight on festering inequities, and this is the moment to finally enact system-wide changes. It takes imagination and the will to make some strategic changes to our current system. We can build a more equitable educational system that lifts all students and creates a stronger, more equitable New York City.

***

Violet Becker is 17 years old, a senior at The Clinton School, an organizer with Teens Take Charge, and former student representative of the Community Education Council for District 2. On Twitter @TeensTakeCharge.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.