Moving Toward a Full Reopening of New York City Schools — The Time is Now

Kids back at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

On Tuesday, April 27, my kids returned to full-time in-person school for the first time since Friday the 13th of March, 2020. But approximately 600,000 kids in New York City are still learning from home. We must do better.

One surprising outcome of this pandemic: My three elementary school daughters -- Sadie, Juno and Ruby -- were thrilled at the promise of more time in the classroom. Their first morning back had the first-day-of-school energy as they giggled at reuniting friends they hadn't seen for a year and rushed in to see their enthusiastic and prepared teachers. In their words, they were "excited and scared at the same time." And the crowd of parents matched their emotions. As the kids literally skipped into schools, parents effusively thanked teachers and administrators. It felt normal...in the most joyful way possible.

We've been more fortunate than most during this period of at-home schooling -- mostly healthy, mostly employed, with flexibility in our professional schedules that have allowed us to create alternatives to Zoom School. But the chance to go back into a classroom -- where a trained professional can invest deeply in their education and where they can interact with their peers -- are academic and social-emotional opportunities we just can't give them at home.

This return was made possible by a few changes: The reduction of social-distancing guidelines from six feet to three feet for elementary schools; the discarding of the ‘two-case rule’ that had led to countless closures and disruptions across the city based on a dubious public health basis; and the additional opt-in period (something we’ve advocated for since the fall) means more of their classmates can rejoin them. Add in the increasing evidence that schools have not been a cause of significant community covid spread and the accelerating pace of vaccinations, and it feels like a safe opportunity to end the school year with nine or so weeks closer to normalcy.

But here's the real issue: What's good for my kids isn't actually solving the problem for most kids around the city. After the latest opt-in period families decided to return roughly 51,000 students back into school buildings. With a school system that serves more than 965,000 traditional public school students that means that 62% of New York City students will not enter a classroom this year, the vast majority of which are students of color. It's clear that the city must do more to hear and meet the concerns of their families if we're to have a successful, equitable full-time reopening in the fall.

So we must continue to raise the alarm: without a clear vision for the fall that's prioritized and resourced now -- something I and others have been calling on the city to provide for many months -- we won't actually have full-time, in-person school for many New York City students, and that will hurt all of us.

There are many reasons families aren't yet returning -- and I’ve been talking to parents and administrators across School District 15 as well as around the city about these reasons. Some are waiting until their families or communities are fully vaccinated. Some want to see how the covid variants play out. Many chose not to opt in to this final period because they have a house-of-cards schedule of childcare that could fall at any moment and it cannot be altered. And for some students remote school removes social anxiety and distractions and is better for their learning.

But it's also become clear that many parents just aren't willing to place a bet on the Department of Education. Years of underfunding have left schools in disrepair, classrooms crowded, and many kids behind. If your school didn't have soap in the bathrooms pre-pandemic, you may not believe the school would have the resources to ensure regular hand-washing. If your classroom was overcrowded to begin with or if you experienced high teacher turnover, you might not think your child's best interests will be served during these uncertain times by heading into uncertain classrooms.

I was frustrated that the city wasn’t collecting or sharing the concerns of remote families in a transparent way, making it impossible to address those concerns. So I decided to ask remote families directly, and working with City Council Member Brad Lander, we had a team of volunteers survey a geographically and racially representative set of parents and caregivers around the city about their plans for the fall. Some news was encouraging: A significant majority plan to return to in-person school in the fall. Other news less so: Most families said they hadn’t been asked about their fall plans yet. Many families brought up specific health questions the city needs to address, and 8-15% said they are unlikely to return to in-person school, which can give administrators and city leaders some guidance for their planning. And one other important note: Principals are the most trusted voices on returning to school for these remote-only families, more than teachers, and far more than the Schools Chancellor or Mayor.

To get more students back in the classroom, we need to ensure schools are truly open five days a week, limit unnecessary closures that create disruptions for families, make sure teachers and staff have had adequate access to vaccinations, and ensure vaccination requirements align with other requirements across our system. Parents need schools to resume early drop-off and afterschool programs -- both for the enrichment of the students and the consistency of schedule. Our high school students must be taught by in-person teachers instead of reporting to classrooms to learn via video. And all of this needs to be communicated proactively and repeatedly, ideally by principals and teachers, who also use this as an opportunity to listen to remote families, ask about their concerns, and help address them.

Furthermore, parents need to understand the alternative: There has been talk of a remote option being offered for the fall, though there are no details or plans. Will that be provided by each school -- overburdening principals to create dual programs for another year -- or run district-wide? Will it be a citywide one-size-fits-all remote curriculum, or a series of remote academies, conducted in different languages and focusing on different learning styles? Until families understand these details, many may not commit to coming back, leaving principals uncertain about enrollment numbers and unable to make clear staffing plans, ensuring a late summer of confusion and frustration for administrators, teachers, and families.

We are seeing an unprecedented infusion of funds into our schools and how that money is spent will speak to our priorities as a community. We could decrease class sizes, expand enrichment opportunities, ensure multilingual communications, add individual and small-group tutoring capacity, invest in community-wide digital literacy, and so much more. And we can try to hold onto some of what schools have experimented with this year: smaller cohorts, more outdoor time, individual learning, a move away from standardized tests. But until we hear that vision -- and help shape it -- many families might imagine a return to in-person school will be reverting to the models that weren't working pre-covid and continuing some that haven’t worked during covid.

Every day that there isn't a clear vision for the fall -- one that truly dives deep into listening to parents, beyond surveys, including through the many community-based non-profits outside the Department of Education that are serving our families and kids on a regular basis; one that draws a clear, consistent picture of what schools will look like, as best as we can know; one that gives us confidence that the "plan" won't change every few weeks, that it will keep our students and teachers safe and, just as critically, be engaging, enriching, and joyful -- is a barrier to a healthier, more equitable, more successful reopening. Our surveying is just a start to understanding these concerns and providing a roadmap for the city -- but we can build on this with more engagement citywide, including empowering principals to reach out to parents to hear their concerns, answer their questions, and give them confidence to come back in-person.

My kids have the privilege of attending a public school where the administration communicates with us through multiple channels and where the Parents Association can fund additional recess coaches to make outdoor time part of every day (including, now, lunchtime), and where, as English speakers with digital literacy, we're able to absorb the range of updates from our teachers, administrators, and city officials. And they’ve had the benefits both of our employer-based health care and of accessible covid testing locations, plus parents, grandparents, and aunts who have all had the opportunity to get fully vaccinated. All of that just isn't true for large numbers of our city's families.

As a result, my kids are back in a classroom, with professional teachers and many of their friends, while many are not. And if that continues in the fall, it'll exacerbate the inequities and segregation in our educational system even further. The promise of a safe and equitable full school reopening needs to work for all students and families, not just mine.

****

Justin Krebs is a parent of three elementary school students in Brooklyn, New York, a parent leader at his own school and in the community school district Presidents Council, and a candidate for City Council in District 39. These perspectives are his own and do not represent the Parents Association or Presidents Council. On Twitter @justinmkrebs.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Community Schools are the Answer: An Open Letter to the New York City Mayoral Candidates

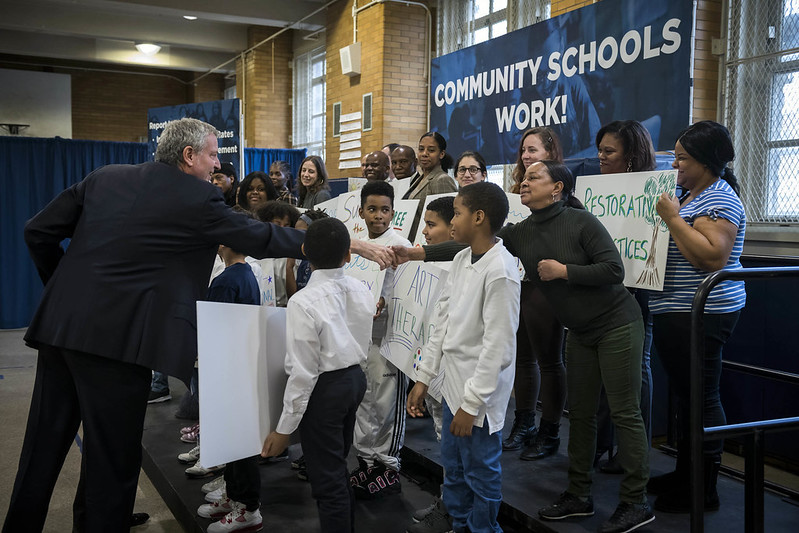

A community school celebration (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Dear Candidates for Mayor:

Among the myriad issues you are discussing during public forums and interviews, none is more important than the education of New York City’s children and adolescents. You have responded to, and raised, several aspects of our educational landscape in these venues but we have heard precious little about whether you support expansion of the city’s community schools initiative, an effort that began in response to a de Blasio campaign promise in 2013—a promise on which he and his administration more than delivered.

Especially now, as New York City recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, voters want to know what you propose as viable strategies to promote health, healing, and learning. In my view, the best answer is community schools.

Community schools organize school and community resources around student success. In 2013, candidate de Blasio said he would increase by 100 the number of community schools in New York City. By the end of his first term, the actual number had increased to more than 250. City Hall and the Department of Education worked together to leverage leadership and funding that allowed these schools—chosen according to the level of unmet need among their students and families—to marshal additional human and financial resources. In alignment with national best practice, each school conducted a thorough assets and needs assessment and then engaged community partners that brought the requisite skills, services, and supports into their schools on a consistent basis.

Even more important than the number of community schools are the results they have achieved. A multi-year impact study of the initiative conducted by the RAND Corporation reported a reduction in student chronic absence as an early outcome and, later, found an increase in academics and graduation rates for all students—particularly for students living in temporary housing and for Black and brown students.

These results were achieved through the mobilization of community resources and their integration into the core instructional work of these community schools—resources like vision screenings coupled with free eyeglasses provided by Warby Parker; mental health screenings and services offered by a combination of public and private clinicians; afterschool and summer enrichment programs that provided child care for working families and extra learning opportunities for students; and a cadre of specially trained social work interns, sponsored by New York City’s six schools of social work, who assist public school students living in temporary housing.

A lesser-known part of the New York City community school story is the role of the Coalition for Educational Justice, a parent advocacy organization that identified community schools as a preferred reform strategy after surveying and consulting with families across the city. As CEJ’s Natasha Capers has written, CEJ implemented a campaign in early 2013 to make improving public education a key issue in that upcoming mayoral race; this campaign included extensive family outreach and consultation over several months. Capers noted that, with the help of a design team of policy experts, CEJ then issued a roadmap for the next mayor that highlighted all the top ideas, including community schools. Parent demand as an instigator for this reform makes its continuation and expansion even more urgent because COVID-19 has demonstrated that the supports and services offered by community schools are needed by New York City’s families now more than ever.

Taken together, these factors—family demand, documented success, new post-COVID realities—make expansion of the community school strategy a no-brainer. Recent action by Mayor de Blasio and the City Council will ensure continuation and growth of community schools through 2022, but advocates are rightly concerned about the future that lies beyond the current administration. The city can use its experience over the past eight years in leveraging and making better use of existing resources while also tapping into new federal dollars, including those allocated for high-need schools in the American Rescue Plan Act.

In addition, the Biden administration has proposed expanding the Federal Full-Service Community Schools Program in the U. S. Department of Education from its current annual budget of $30 million to $442 million in 2022. New York City should be first in line to capitalize on this national momentum. But, to do so, we need a Mayor who believes in the idea of every school a community school.

***

Jane Quinn is currently a doctoral student in Urban Education at the City University of New York. From 2000 through 2018, she served as Director of the Children’s Aid National Center for Community Schools.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Cannot Fine Its Way Through a Covid Recovery

"Save Small Business" (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

The next few years in New York City will no doubt be challenging.

In a few months, a new mayoral administration and the next City Council will inherit the worst financial situation in 20 years. The path ahead will be difficult as we try to lure tourism and business back to New York, in hopes of closing budget gaps that will threaten vital social services above all else. We must learn from the lessons of the past, however, to guarantee this isn’t a recovery built off the backs of those already struggling to get by.

When New York City faced a similar budget crunch 20 years ago after 9/11 caused a mini-depression, Mayor Bloomberg turned to fines, especially around parking violations, to help meet the shortfall. These measures were as controversial then as they are now, feeding into a national trend in which monetary penalties to deter illegal behavior became a revenue stream. Research has shown, however, that fines and fees, no matter the type, disproportionately impact communities of color and immigrant populations. The thrust of our city’s recovery should not stem from regressive policies that push everyday New Yorkers deeper into crisis rather than out of it.

This also applies to small businesses, the heartbeat of our communities. The city must not look to them as an easy target to build back up its coffers. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, the city has continued to target small business owners with hefty fines for minor infractions. While finding new streams of revenue will be an important factor in dealing with the budget shortfall, onerous fines and overzealous enforcement of minor violations cannot continue to be the solution. Economic data presented last month shows that 78% of New York State businesses with fewer than 500 employees are still struggling from the impacts of covid, according to a March report from State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli.

Those numbers become even more real when you walk down Austin Street, Queens Boulevard, or 108th Street in Queens and ask business owners, many of whom are immigrants trying to live the American dream, what the last year has been like.

There are simple steps we can take to lift all boats. We must take a completely new approach that prioritizes supportive case-workers over penalty-issuing inspectors. That’s not to say a business owner who price-gouges face-masks or a restaurant owner who keeps a dirty kitchen shouldn’t be punished. But those who try to adapt to the constant change in rules shouldn’t be a revenue line in the city’s budget.

Next, the Department of Small Business Services must ramp up its outer borough outreach. The only time many here in Queens interact with the agency — or the city as a whole — is when an inspector makes an unannounced visit. The laudable efforts by SBS during covid shouldn’t go away once we declare victory on this virus. The next mayoral administration and City Council must work together to create a post-covid small business task force that allows New Yorkers to responsibly follow their dreams and provide for their families.

Third, we need to completely stop relying on fines as a first-strike warning for small businesses in their first year. Instead of fining an entrepreneur into collapse, we need to work with them to rectify the issue in a constructive way as opposed to meeting a violation quota.

These steps mark only the beginning of what needs to be a fundamental restructuring of the relationship between our small businesses and those tasked with enforcing our city’s rules and regulations. There’s a lot of work that will need to be done, but I know it’s possible to ensure that we can build Queens and New York City back stronger than ever before, with a budget that is balanced and an environment where small businesses can thrive. As we continue to recover from the pandemic, we must take advantage of the opportunity to create a fairer city that looks out for all its residents. In the City Council, I’ll make sure that becomes a reality.

***

David Aronov is a Democratic candidate for the New York City Council in Queens’ 29th District. On Twitter @DavidforQueens.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Homeownership Supply is the Affordable Housing Blind Spot in New York City

Housing (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office)

Charged with leading post-covid New York to a more equitable future, our next mayor should increase opportunities for New Yorkers to build equity through affordable homeownership.

Historically a blind spot in our city’s, state’s, and country’s affordable housing discussions and budgets, which tend to focus on rentals, affordable homeownership is a way for low-income people to begin to build wealth and for us as a city to reduce racial and economic inequality. Homeowners are wealthier than renters at every income level, and for the majority of homeowners most of their wealth comes from their homes.

Homeownership is elusive for most New Yorkers. In 2018, the last year of available data, just 33% of residents owned their home, dipping as low as 18% in the Bronx. White New Yorkers, at 43%, are far more likely to own their home than Black (27%) or Hispanic New Yorkers (17 %), and it’s getting worse: a recent report from the Black Homeownership Project showed that the Black homeownership rate has dropped by 13% over the last two decades citywide, preventing long-term equity building and exacerbating racial wealth gaps.

Yet, expanding new opportunities for working families, especially of color, to purchase affordable homes is often left out of New York’s housing policy discussions entirely. When it is brought up, even within the affordable housing sector, the conversation is often focused on demand-side challenges like down-payment assistance, credit-building, first-time homebuyer education, and ending discriminatory practices in the homebuyer market. These issues are important, but they miss the larger crisis: there are not enough homes available at prices accessible to working-class households to move the needle.

A Center for NYC Neighborhoods analysis of ACRIS data showed that in 2019, there were approximately 9,000 homes purchased for $420,000 or less, which is considered accessible with the right financing to low- and moderate-income homebuyers. In a city of 8.3 million people and over 1 million owner-occupied homes, this number is shockingly small and makes up only 22% of all home purchases of 1-4 family homes, condos, and co-ops.

To make matters worse, homebuyers, even with the right credit, down-payment assistance, and mortgage qualifications, were beat out by cash buyers over half the time. According to a recent study from Center for NYC Neighborhoods, 52% of all low-priced homes were bought with cash, often by private equity groups, limited liability corporations, or investors rather than individuals seeking to move in.

The good news is that the conversation is changing in a significant way, and our next mayor has a blueprint from 90-group strong The United for Housing coalition with specific recommendations to expand affordable rental and homeownership housing.

It calls on the next mayor to expand and reform the city’s Open Door homeownership construction program, invest in preservation strategies that would convert rental properties into resident-owned limited equity cooperatives, and utilize Community Land Trusts as a method to keep people in their homes while creating permanent affordable homeownership opportunities for low- to moderate-income New Yorkers.

Better yet, the plan creatively challenges institutional processes like New York’s tax lien sale and down-payment assistance programs, putting forward solutions that would utilize limited financial resources to bolster household and community assets for residents and neighborhoods. In other words, the report helps arm our future leaders with the detailed policies they need to tackle this crisis – and candidates are listening.

Some of the candidates for our city leadership have addressed these disparities and put forward specific homeownership policies that expand the conversation past the demand-side solutions that place the onus on the homebuyer to break into the homeownership market. Still, the issue hasn’t been thoroughly addressed in the larger housing debate. New Yorkers deserve to hear more from candidates about how they will not just help them rent an affordable apartment but buy one and build wealth and own a piece of their neighborhood.

Affordable homeownership supply cannot be an afterthought in a sea of rental development strategies. Even in New York, the idea of homeownership cannot be a pipe dream reserved only for the rich or famous. Increasing affordable homeownership opportunities must be a central pillar of the next mayor’s vision to build the smart, progressive, and equitable city New Yorkers deserve.

***

Matt Dunbar is the VP of External Affairs at Habitat for Humanity New York City, collaborator with Interboro Community Land Trust, and an Advisory Board Member of the New York Housing Conference. On Twitter @misterdunbar & @HabitatNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In Our Covid Recovery and Beyond, Teachers Should Get the Support They Deserve

A teacher at work (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

I had missed the call from my son’s school because I was on yet another Zoom. When I called back, my world turned on its head as I heard words like “suspicious package” “white powder,” and “lockdown.”

When I reached my son’s school on the Upper West Side, I found the block cordoned off, flashing police cars and ambulances lining the block, people in stark white hazmat suits going in and out of the school and terrified parents like me waiting on the periphery.

This ordeal would drag on for hours but the teachers kept their cool and kept my little guy and his schoolmates fed, happy, and safe.

Teachers are heroic. We ask them to be everything to everyone, but, as a nation, we have paid a lot of lip service to honoring them. New York City has worked hard over the years to support pedagogues and partnered with grassroots organizations like March For Our Lives to advocate for change. Last week, we celebrated our teachers during Teacher Appreciation Week. Now, we are calling on our nation to commit to supporting educators and providing them with the resources to not only do the jobs they are hired to do — teach — but the critical work they end up doing: being our children’s protectors and social workers.

Schools should be havens, places where all students, teachers, and staff feel safe. Sadly, as a society we have drifted away from that ideal. At March For Our Lives, young leaders have recounted to us time and again the feelings of dread and fear they feel in their own schools, too. We were founded in the wake of a horrific mass shooting, and over the years young people have fought to lift up the great needs in our nation’s schools and communities — the real world challenges that include the threat of violence.

Nearly 40,000 people are killed by firearms each year, and in recent years firearms have become the leading cause of death in children and adolescents. Teachers are often on the front lines caring for the trauma and emotional toll that this loss inflicts on our communities and on our young people, and yet they’re too often overburdened and under-resourced. The pandemic has only exacerbated these challenges.

At March For Our Lives, as we’ve expanded our mission beyond school-based mass shootings to confront gun violence across our communities, we’ve heard time and time again that we need laws and trusted adults to look out for kids — to work to create the safest environment for all of us by investing in solutions that prevent violence from occurring in the first place like violence intervention programs, so that places like schools remain places of care and learning rather than fear.

In New York City government, our leadership has recognized that COVID-19 is taking a profound toll on the mental health of our youth. And so the city took action by increasing direct mental health support for thousands of students in the neighborhoods hardest hit by the novel coronavirus.

Spearheaded by the city’s Taskforce for Racial Inclusion and Equity, mental health workers are working with students at 350 schools in the most economically vulnerable neighborhoods. Students who have experienced trauma – whether that be a severe illness or death in the family or a parent’s job loss – now have access to group therapy sessions.

Not only are these mental health specialists providing direct services to students, but they are also providing mental health education to caregivers and school staff so that they can help address students’ mental health needs. It’s a model we believe is worth replicating across the nation.

As we look to all the ways to build back better from covid, we need to add more supports and resources for teachers into our plans for a “new normal.” There were already gaping disparities in education pre-pandemic. As a society, we are going to have to work even harder to overcome these inequities that have only grown worse in the past year.

More than a year into this pandemic, with millions of students across the U.S. still learning from home, undoubtedly parents everywhere have gained a new appreciation for all teachers do. So let’s not just talk the talk, but walk the walk.

As for my son, while I stood by helplessly outside the school with the other parents, his teacher texted to say the kids were playing, making art, and blissfully unaware of the chaos around them. Apparently, the police officers were “special guests.” He still thinks that was “the best day ever” at school. He was actually bummed to leave school – for which I am eternally grateful. Teachers are superheroes.

***

Penny Abeywardena is the Commissioner of NYC Mayor’s Office for International Affairs and Alexis Confer is the Executive Director of March For Our Lives. On Twitter @PAbeywardena and @AlexisConfer.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Next Mayor Must Finally Address Our Commercial Affordability Challenge

(photo: Edwin J. Torres. Mayoral Photo Office)

New Yorkers know that love of neighborhood is synonymous with love of small businesses. But in 2020, we suddenly learned just how thin the reserves of our shops, restaurants, and bars can be. Many New Yorkers responded by doubling down on that love of local; meanwhile, too many businesses felt deeply let down by their elected officials as they faced mounting rent debt and great uncertainty. And so when small business owners vote in June’s Democratic primary to elect the next mayor, many will be voting for the candidate they believe can best revitalize the main streets of our neighborhoods.

Most candidates are talking about small businesses. Good.

There is widespread agreement to cut more red tape. We may finally get that one-stop portal for all permitting needs. There may be stimulus through sales tax holidays. But these are mostly lightweight fixes. None of them address the more worrisome trend that since the early 1980s, small business start-up has been declining while concentration in most industries has grown.

Between 2000 and 2015, we lost 108,000 independent retailers. Pre-pandemic, Black business ownership was only at 2% in New York City. To create a thriving small business economy, the next mayor has to address this city’s long-term commercial affordability challenge, which plays out in two ways: in how market rents are determined and in who gets access to capital for business start-up and growth.

Between 2007 and 2017, retail rents rose by 22% citywide, a rate that was much greater in pockets like Williamsburg and doubled in neighborhoods like Soho. Now the pandemic has brought incredible variation to the marketplace. Here’s a snapshot: CBRE data shows that rents are especially down in Manhattan’s higher-end retail corridors. According to reporting in The City this March, “The deals [being discussed] include periods of free rent - along with rent being a percentage of the sales in the first two years, followed by a reset to market rents in years three and four.” This was echoed by the Wall Street Journal, which cited brokers seeing lease resets returning rents to 2019 levels. It also reported very short-term leases being signed as well as landlords keeping spaces off the market to lock in higher rents later under a recovered economy.

The New York Hospitality Alliance’s December survey of more than 400 restaurants and bars found that 86% of businesses reported failing to renegotiate their leases. I know of a Gowanus performance venue currently being asked to renew their lease at a considerable increase while another business peer inquired on a property and was told that the landlord was only considering chain tenants. By contrast, the business improvement district (BID) for Park Slope’s Fifth Avenue has seen more new leases signed than the number of businesses that closed in 2020. In sum, deals are happening but we would be absolutely naive to think the pandemic will only bring about long-term affordability and small business opportunity.

This lack of affordability has been driven by the interplay of big brands, banks, and developers. Online retailers have realized that they still need brick and mortar locations while multinational chains have been eager to expand beyond the high-end retail corridors of Manhattan into other boroughs. In such cases, rent is often parked as an advertising cost and affordability is not a function of revenues estimated to be earned in that location. And as smaller landlords have exited in place of larger developers, the latter tend to hold commercial mortgages underwritten by mostly national banks that have stringent requirements on rent rolls and a comfort for chain store tenants.

These banks are also determining who gets access to capital that can help create affordability for entrepreneurs. The four dominant banks in the U.S. have been lending less to small businesses since the Great Recession. Black entrepreneurs in New York City have overwhelmingly identified access to capital as their number one challenge. Under the pandemic, more small business owners have taken on debt and some are in personal bankruptcy. Meanwhile, Shake Shack has announced that it is borrowing $225 million to fund a massive expansion.

The result is that giant corporations, banks, and developers are all too often determining the landscape of our neighborhoods while small businesses are seen as a problem to fix through mostly technical assistance. So what is the next mayor to do?

One approach is to let markets be markets and accept that New York City has a “sticky rent” problem but create ways to get tax dollars back to small business tenants or to landlords who rent to small business tenants under favorable terms . A different approach would be to try to actually lower the rents themselves by creating caps on increases in high residential neighborhoods, either directly through a regulatory board or indirectly by altering the marketplace of what kinds of businesses can bid on a space, such as the zoning permissions San Francisco uses to keep chains out beyond their downtown corridor or the law North Dakota uses to keep out chain pharmacies. A vacancy tax on viable commercial spaces would be another tool in this approach. At the same time, the next mayor needs to consider how to grow both the assets and locations of Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) to get capital into the hands of more entrepreneurs.

Revitalizing our main streets across the five boroughs for the long-term is a massive challenge but with the right dose of ideas, research, and courage, we can make progress. The next mayor must lead the way.

***

Natasha Amott is a small business owner and active in small business advocacy. On Twitter @Natasha_Amott.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Shelter Security Workers Like Me Need the City Council to Ensure We Can Afford to Live

Quintona Armwood, the author

About eight years ago, I lost my apartment when I was pregnant with my son, Kailyn. After experiencing for myself what it’s like to be homeless, to not have a permanent place to live, I got a job as a security officer at a homeless shelter. I could relate to the shelter clients, so I set out to help them get back on their feet.

I loved my job then and I still do now. However, because of the poor work conditions at the shelters, I am only a few steps away from being homeless myself again.

The $16.50/hour that I receive is still not enough for me to afford my own apartment. Today, I live with my mom and work two full-time jobs: one as a security officer at Crystal’s Place shelter in the Bronx and another as a medical assistant at a private clinic. Because I work about 16 hours on an average day, I leave my son in my mother’s care. On the days when I’m lucky, I get to come home when he’s still awake and tuck him into bed.

I have to make hard choices every day. Whether it is between being able to support my son through school or putting food on the table, being able to pay my electricity bill or taking my son to a professional to address issues related to his ADHD.

Every day, I ask myself if I am failing my son as a mother. I ask myself if I am failing my mother, a military veteran who has sacrificed so much for me and for our country. In reality, the system is failing people like me.

As private shelter security officers, we work in dangerous and stressful environments with little pay, no meaningful benefits, and little training on how to actually perform our duties. Even though we are expected to protect New York City’s most vulnerable, we cannot even sustain and protect ourselves. We perform essential duties for our city, yet still have to often rely on government services such as Medicaid for our own health and safety.

We have the opportunity to change that once and for all. The Safety In Our Shelters Act, or SOS Act, (Intros. 1995/2006) in the New York City Council would raise the standards for workers like me and ensure that privately run shelters are providing decent wages, benefits, and training opportunities to security workers.

With the SOS Act, I would have the training I need to de-escalate conflicts that may arise in the shelters so I can better protect shelter clients. Instead of relying on Medicaid, I could have health insurance through my job like all essential workers should. I could make enough money to address my son’s special needs, or perhaps even be home to cook him dinner, spend time with him, and kiss him goodnight.

As the daughter of a military veteran and a single mother, I know what it means to make sacrifices for what you love. I also know what it means to fight for what’s right. The New York City Council has repeatedly stood up for workers like me and given us a shot at a fair life in this city. We ask them to pass the SOS Act without delay.

***

Quintona Armwood is a security officer and a mother.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Latinos and the 2021 City Council Elections in the Bronx

Latino leaders in the Bronx (photo: Ruben Diaz Jr.)

This piece is part of Latino Vote ‘21, a series of columns on the Latino vote and the 2021 New York City elections.

I mentioned in my previous column introducing this series on the Latino vote in the 2021 New York City elections that the growing Latino presence in New York has meant a slow but steady increase in Latino voting participation. This increase may possibly lead to greater Latino representation across the city. This city election cycle -- with all of city government on the ballot in June primaries and a fall general election -- can prove this theory right or wrong.

We begin our exploration in the Bronx, the borough Latinos call “El Condado de la Salsa” (the borough of Salsa music), with five City Council districts that are contested and have large Latino populations — Council districts 11, 13, 14, 15, and 18.

I am deliberately omitting district 16, which I briefly highlight here because interestingly enough the district is majority Latino, from that list. However, even there, Latino voting participation lags behind other ethnic groups, with African-Americans and a growing African population being the next largest groups. The district has been represented by African-Americans for decades, the most recent being Vanessa Gibson, who is now running for Bronx borough president. Helen Foster represented the district before Gibson, and replaced her father, Wendell Foster. While Latinos make up the largest group in the district, no Latino candidates are on the ballot for the June primary this year.

Our look into the Council districts begins in the northwestern part of the Bronx, the 11th district. Eric Dinowitz, son of Assemblymember Jeffrey Dinowitz, recently won a special election, besting a number of candidates, one of whom was a Latina, Mino Lora, who is running again in the June primary. The 11th Council district demographically points to a trend that is happening in other parts of the city—Latinos have outpaced other ethnic groups in voting population numbers. Interestingly, Latinos are now the largest ethnic group in this district that has been historically represented by non-Latinos.

In addition to Lora, who has received the endorsement of a number of progressive groups and leaders, Marcos Sierra, a current Democratic District leader, is the other Latino in the race. Having two Latinos on the ballot does not bode well for either of them since it presents the likelihood of a divided Latino vote.

Further east, the 13th Council district is currently represented by Mark Gjonaj, who is not running for re-election. It is likely that Latinos will gain representation with this open seat, especially since Marjorie Velazquez, a top candidate for the position, has garnered much support and is the only candidate in this race that has received public matching money (she narrowly lost to Gjonaj four years ago). A Velazquez win will not only increase Latino representation at the Council but also increase female representation in that august legislative body that has seen a significant gender imbalance.

Further west lies the 14th Council district. I believe this open seat, currently represented by term-limited Bronx borough president candidate Fernando Cabrera, will be the most contested seat in the Bronx. There are six candidates on the ballot and five of the six have already received over $100,000 in public matching money. Several, like Haile Rivera, Yudelka Tapia, and Adolfo Abreu have had long-standing relationships and community work in the district. Fernando Aquino, also contending for the post, was a communications director for former Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, and Pierina Sanchez has garnered the support of numerous elected officials and labor unions. This race is one to watch.

Right next door to the 14th is the 15th Council district. Oswald Feliz recently won the special election there to replace Ritchie Torres, who won his election to Congress last June. Some of the other candidates that ran in that election will vie for the post again in June, including Ischia Bravo, who garnered labor support in her bid for the seat. Feliz, whose victory surprised many observers, had the support of Congressional Rep. Adriano Espaillat.

Feliz’s victory in the 15th Council district is the first for a Dominican. The seat has been represented by Puerto Ricans for decades. This victory marks a shift that has long been observed because of the steady increase of Dominicans in New York. It is clear that Dominican voters have now become a powerhouse in the Bronx. Though according to modeled data by the likes of prominent voter data companies L2 and Catalist, Puerto Ricans still outnumber Dominicans in the voting population, Dominicans are quickly inching their way to the top. Feliz’s victory points to this reality.

The last Council district we are looking at in the Bronx is the 18th. After serving a term in the Council and losing to Ritchie Torres in last year’s congressional race, the Rev. Ruben Diaz Sr. has decided not to seek re-election. Several candidates are vying for the seat, including some returning contestants like Michael Beltzer and Amanda Farias. There’s also William Rivera, the district manager of Community Board 9, who recently received the endorsement of outgoing Bronx Borough President, Ruben Diaz Jr. Others who are on the ballot and have received public funding include Mohammed Mujumder, who received the maximum.

The two front-runners seem to be Farias and Rivera. Farias has earned the support of many labor and activist organizations and elected officials across the city, and has received the maximum in public funds. Rivera, who has also received the maximum and now Diaz, Jr.’s endorsement, will be a top contender and would need to use every penny possible to offset the organizing efforts of labor and others on behalf of Farias. A Farias victory would see the return of Latina representation at the Council in this district some years after the district was represented by Annabel Palma.

All in all, the quality of Latino candidates in the Bronx -- the city’s most-Latino borough -- is impressive, especially since there appears to be an increase in political activity among young Latinos, evident by the number of hotly-contested races featuring young Latino candidates.

My next column will look at another hotly contested race in the Bronx, this one the big enchilada—the Borough President’s race.

This piece is part of Latino Vote ‘21, a series of columns on the Latino vote and the 2021 New York City elections.

***

Eli Valentin is an adjunct lecturer at Union Theological Seminary, a frequent guest political analyst at Univision NY and author of the forthcoming, Reinhold Niebuhr: A Political Life. On Twitter @EliValentinNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Just as Other Places Have Done, New York City Can Preserve Jobs and Tradition with Electric ‘Horseless’ Carriages

Horse carriage ride (photo: @shinyasuzuki)

Flashback to the 2013 New York City mayor’s race where one front-and-center issue that ultimately helped propel Bill de Blasio to City Hall was whether to ban horse-drawn carriages in New York City. Eight years later, not much has changed except for little to no attention on the issue in the 2021 mayor’s race. As long-time horse advocates, we believe this business to be inhumane and dangerous — both for the horses and the public — particularly in a congested city like New York.

We’ve long wanted to see the end of the urban carriage horse trade. However, one key thing did change between 2013 and now and that is innovation. There is now a new alternative that would preserve this long-time New York City tourist tradition, including the jobs that come with it, while protecting the wellbeing of the horses and the public.

The question we asked ourselves is how could we achieve a similar effect as an outright ban, but also get the drivers and their union to agree it would be beneficial for all? To find the answer, we turned to our friends across the border and to what a growing number of cities around the world are starting to implement in electric-powered carriages.

In August 2019, we traveled to Guadalajara, Mexico on a fact-finding mission to learn about the new electric carriages replacing the longtime horse carriages in that city. Two years earlier, Enrique Alfaro Ramírez, the mayor of Guadalajara at the time, signed a law to ban the horse carriages, stating, “we cannot continue to mistake the idea of tradition with animal abuse.” We were impressed with what we saw in this lovely, historic, global city – the second largest in Mexico and one of its most important cultural centers.

At the time of our visit the transition was halfway complete and we talked to several drivers operating the electric carriages. They told us how much they enjoyed the experience; how their income was much higher; how they did not have to worry about their horses’ upkeep; or the disapproving public – something all carriage drivers deal with in a very controversial business. With the assistance of a local attorney who also runs an animal protection organization, all the horses were placed in good homes.

We returned to New York eager to share what we learned and to start a serious dialogue about this exciting new option -- to reimagine New York City with electric carriages. Unfortunately, the pandemic brought everything to a screeching halt, including the city’s tourism industry with many cultural institutions, restaurants, and hotels forced to close and nearly $5 billion in local tax revenue gone.

As tourists slowly trickle back to New York City as we approach the summer season, we have an opportunity to build back better, which includes exploring a renewed industry of electric carriages that will not only save existing jobs but create new ones. And we are starting to see a worldwide movement.

As tourists slowly trickle back to New York City as we approach the summer season, we have an opportunity to build back better, which includes exploring a renewed industry of electric carriages that will not only save existing jobs but create new ones. And we are starting to see a worldwide movement.

In addition to Guadalajara, electric carriage rides are offered in Mumbai, India; Cologne, Germany; and Dubai, UAE, to name a few. Some cities have outright banned the trade, eliminating the horse carriages with no replacement alternative, including Salt Lake City, Chicago, and Asheville in the U.S. and international cities including Barcelona , Old San Juan, and Montreal.

New York City could become the first U.S. city to make this shift as responsible and compassionate tourism has evolved and people become increasingly concerned about the commercialized use of animals in tourist entertainment, like what we see around Central Park. In early 2020, a carriage horse named Aysha collapsed in Central Park and later died. Another horse collapsed in the park in December but was forced to get up and continue to work. These disturbing incidents, two examples of many, are a black mark on the business and the city. A horse in congested and chaotic traffic is a horse at risk. It does not have to be this way.

As with Guadalajara, electric carriages will need wide-ranging support and we recognize this isn’t a change overnight. The newly-elected mayor, the new City Council speaker and Council, the unions, business community, and all the key players would need to come together next year. But we should be talking about it right now.

In Guadalajara, no one thought this was possible, but after much work and negotiations, what once seemed impossible became a win-win for all involved. We know many things will need to be worked out, including how the evolution is funded; new regulations to allow the electric carriages to operate; installing charging stations; and determining where the carriages would be parked overnight – and developing a plan to ensure that the horses are placed in sanctuaries or good homes.

But it’s all doable. New York is a city of endless possibilities and opportunity. We just need the will to implement a viable alternative that improves the quality of life for all, while preserving the business in a different form. Come January, we hope the next mayor seizes that opportunity.

***

Elizabeth Forel & Susan Wagner are Co-Founders- Committee for Compassionate & Responsible Tourism.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Passed Outdoor Dining Into Law, Now We Must Improve It

Ourdoor dining (photo: @nycgov)

In March of 2020, COVID-19 brought the pulse of our vibrant city to a devastating halt. New Yorkers were directed to stay in their homes, subways shut down and buses cleared out, offices closed, small businesses shuttered, and the vibrant action stopped in the restaurants that are so essential to our culture and quality of life.

Now, I may be biased, but I believe that Brooklyn has some of the best food options the city has to offer -- and some of the hardest working service workers, too! So when businesses in our communities reached out for urgent relief while the pandemic raged, I sponsored and passed legislation for outdoor dining to be allowed all across New York City.

It worked. Restaurants expanded onto our sidewalks and into our streets. Relieved owners received a newfound ability to serve customers in a safe manner after months of lost revenue. Residents were delighted to leave their homes and apartments, helping to relieve cabin fever and offering a glimmer of “normalcy.” Kitchen and wait staff had work. We also found an amazing opportunity to reimagine our streetscape, reclaiming precious sidewalk and street space for New Yorkers — building community and providing an economic lifeline.

The outdoor dining program saved countless restaurants from bankruptcy while creating more space for residents to enjoy our street life, lifting the spirit of our city in an otherwise dark period. As we emerge from this pandemic, outdoor dining is a successful program we should keep, not just for our neighborhoods, but for all the small businesses still fighting to survive. With the obvious benefits for employers, employees, and our city as a whole, it deserves to keep going, especially if we learn from past lessons and make key improvements.

We must make the program more accessible to small businesses in every corner of our city by increasing educational outreach, providing technical assistance so businesses are set up for success, and streamlining the cure process for infractions.

From the taquerias and dim sum restaurants of Sunset Park to the roti shops in Flatbush, what makes New York City’s restaurant scene so tantalizing is its diversity. We need to ensure that restaurant owners in outer-borough communities of color -- those neighborhoods hit hardest by the pandemic -- have the tools necessary to successfully utilize the outdoor dining program. We can do this by increasing targeted, multilingual, educational outreach about the program and how to use it. Encouraging more restaurants to participate not only helps the individual businesses, but will also uplift communities that have suffered the most during this pandemic. Increased outdoor dining will attract more customers to locally owned businesses and create more vibrant outdoor spaces, powering neighborhood recoveries.

Getting an outdoor dining program up and running at a restaurant is just one piece of the puzzle. We also need to make it easier for restaurants to successfully use the program. This means ensuring that technical assistance and support is readily available. Let’s set businesses up for success by equipping restaurant owners and workers with knowledge about how to set up a safe and compliant outdoor dining space and avoid fines. While several agencies are able to levy fines, information about how to avoid and cure violations should be easily accessible from one central source and available in all languages. Restaurant owners and workers need to spend this time making their businesses successful, not navigating a needlessly complex bureaucracy of city government in order to avoid being fined.

As we begin to emerge from pandemic restrictions, we have to look back and assess our government’s response to the challenges we faced. We can be proud of what we did with outdoor dining, creating a policy that extended a critical lifeline to our residents, reimagined how our streets and sidewalks could be used, and provided our neighbors with a safe and much-needed escape in a time of great isolation.

Moving forward, we need to make sure that the program becomes permanent and harness its benefits while improving access and usability so that all small business owners can take advantage of this opportunity as we recover. Our restaurants have intersectional relationships with our communities, creating jobs, particularly for immigrant communities, serving as local gathering spaces, and giving hard-working New Yorkers a place to blow off steam. I want to build on this creativity and excitement, and if elected Brooklyn Borough President I will continue to explore innovative solutions that open up our public spaces in ways that benefit all Brooklynites.

***

City Council Member Antonio Reynoso represents parts of Brooklyn and Queens. On Twitter @CMReynoso34.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Voters Face Sharply Reduced Choices in Future Elections

Voting (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

In April 2020, Governor Andrew Cuomo virtually forced the New York legislature to make severe changes to New York’s ballot access laws, by inserting those changes into a budget bill, which had to pass in order to avoid chaos. If those changes are not reversed, New York voters will invariably see only two candidates on their general election ballots in 2022 for almost all congressional and statewide races. In 2024, for president, chances are also high that they will see only the Democratic and Republican nominees on the November ballot.

One change increased the petition for statewide office from 15,000 to 45,000 signatures required to appear on the ballot. However, for 2020 only, Governor Andrew Cuomo reduced it to 30,000 signatures by executive order due to the pandemic. Even with that reduction, not one statewide independent petition succeeded in 2020. In the entire history of New York’s government-printed ballots, which originated in 1890, this was only the second time when not one statewide petition succeeded in a presidential or gubernatorial election year. The only other instance was in 1956, when the only two groups that tried, the Socialist Labor Party and the Socialist Workers Party, had their statewide petitions challenged and rejected.

In the spring of 1992, when Ross Perot was starting to run for president as an independent, the New York petition requirement was 20,000 signatures. Although Perot was very popular in the national polls, and was rapidly getting on the ballot in all the other states, New York legislators were concerned that Perot would not be able to get on the ballot in New York. So they eased the petition requirement, to 15,000 signatures. The bills that made that liberalizing change, S7922 and A11505, were obviously motivated to avoid the embarrassment of Perot getting on the ballot in all states except New York, because the effective date for the reduction in signatures for other statewide office was set in 1993, but the reduction for president went into effect the day the bill was signed. Governor Mario Cuomo signed the bill on May 8, 1992. Perot did then get on the ballot in New York and all other states.

If the 1992 session of the legislature had a plausible fear that 20,000 signatures was too difficult for someone as popular as Ross Perot, it makes no sense that Governor Andrew Cuomo chose 45,000 for future statewide petitions, unless he desired to block all future statewide independent petitions.

The severity of the statewide petition increase was not obvious in 2020, because New York already had eight ballot-qualified parties. The Libertarian, Green, and Independence Parties were each free to nominate someone for president without a petition, and did so. Therefore, New York voters had five candidates for president on the general election ballots: Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Jo Jorgensen (Libertarian), Howie Hawkins (Green), and Brock Pierce (independent). The SAM Party, which was also on the ballot, chose not to have a presidential nominee. The Working Families Party listed Biden; the Conservative Party listed Trump.

But, the 2020 ballot access change had another provision, increasing the requirements for a group to meet the definition of a ballot-qualified political party. It increased that definition so severely that four of New York’s parties are no longer automatically on the ballot. If they want to run in 2022 and future years, they will first need to get 45,000 valid signatures for their top-of-ticket nominee. To put the difficulty of getting 45,000 signatures in perspective, note that in 2020, not one independent candidate, and not one minor party, successfully completed any petition anywhere in the nation that exceeded 5,000 signatures, for any office. Granted, petitioning in 2020 was especially difficult due to the covid health crisis.

Defenders of the new definition of “political party,” a group that polled at least 2% for the office at the top of the ticket every two years, in gubernatorial and presidential elections, argue that the Working Families and Conservative Parties meet the new definition, so that New Yorkers will still have four parties to choose from. But in New York, the Working Families Party has never, in its 23-year history, nominated anyone for statewide office who was not the Democratic nominee. For the U.S. House, the Working Families Party also almost never runs anyone other than the Democratic nominee. In 2020 it had only one nominee for U.S. House who was not also the Democratic nominee, and that was an unintended accident, and if the Working Families Party had won in court, even that one nominee would have been replaced by the Democratic nominee.

The Conservative Party generally nominates the Republican nominee. For president, it has never nominated anyone who was not also the Republican nominee. For other statewide offices, it has not run someone who was not the Republican nominee since the U.S. Senate race in 2004. For the U.S. House, it almost always nominates the Republican nominee. In 2020, there were only two districts in which it ran someone against the Republican nominees. Therefore, the presence on the ballot of the Conservative and Working Families Parties barely adds to the list of candidates.

In 2020, in the U.S. House races, 17 of New York’s 27 races had at least three candidates on the ballot, but that was almost entirely due to the fact that the Libertarian, Green, and SAM Parties had their own nominees. Without those parties on the ballot in future elections, virtually every U.S. House race, and the vast majority of state legislative races, will have only the Democratic and Republican nominees on the ballot.

New York has been one of the states with the most third party and independent choices on the ballot for its entire history, and New Yorkers have been the voters most likely to elect such a candidate to Congress, compared to the voters of the other states. Individuals who were not Democratic or Republican nominees were elected to Congress from New York in 1947, 1948, 1949, and 1970. In the last 100 years, no other state can match that level of political diversity in congressional elections. If New York wants to keep its storied political diversity, the ballot access changes of 2020 must be reversed.

***

Richard Winger is the publisher of Ballot Access News.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.