Key Fixes for New York’s Broken Parole System Await the Governor’s Signature

The governor's signature (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

It wasn’t the eight months of military-style, intense shock incarceration that finally broke me; it was my parole officer.

After my incarceration at Lakeview Shock Incarceration Correctional Facility for non-violent offenders in Brocton, New York, I quickly realized I was living in constant fear of reincarceration. My parole officer had issued strict conditions such as travel limitations and unreasonable curfews, which prevented me from getting to work on time. There were incessant home visits, often at 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning. I was convinced my parole officer was scrutinizing my every move, just waiting for a reason to issue a technical parole violation.

As it was for me, the fear of reincarceration is an everyday lived reality for over 35,000 people under active parole supervision in New York; a fear that is crippling for those trying to reenter the workforce, rebuild their lives, and heal their families. New York’s parole system is broken. It destroys lives and communities. It costs taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. It needs to be reformed.

According to Columbia University Justice Lab, 40% of people sent to New York prisons in 2019 were not remanded for new crimes, rather they were reincarcerated for technical violations such as failure to report to a parole officer, living at an unapproved address, or missing a curfew. New York reincarcerates more people for technical parole violations than almost any other state in the country.

The racial disparity in incarceration for technical parole violations is also undeniable. Black and Latino people are much more likely to be incarcerated for parole violations than white people. In New York City, for example, Black people are incarcerated for technical parole violations at 12 times the rate of whites.

Financially, New York taxpayers are paying for a broken parole system. Parole is administered by the state government; the state is fiscally responsible for supervising people on parole supervision. However, people in violation of parole are incarcerated in local city jails such as Rikers Island in New York City, thus local governments become responsible for footing the bill without reimbursement from the state.

In 2019, state and local governments together spent more than $680 million to incarcerate people for technical parole violations, even though there is no evidence that this led to a meaningful increase in public safety.

Public safety is not created by putting more of the public back in prison. It begins by creating safe communities. And safe communities are not synonymous with increasing jail and prison populations. Safe, healthy, and prosperous communities arise from supporting and strengthening reentry processes. They result from humanizing people and giving them a fair and fighting chance at rebuilding their lives, and by creating access to opportunities and economic mobility.

Parole was worse than being incarcerated for me. The stress and anxiety that I experienced led to debilitating mental and physical health conditions. The constant policing and pressure by my parole officer and the fear of reincarceration were so overwhelming that I decided to serve out the remainder of my sentence in prison.

While no longer in prison or on parole, I am still experiencing the long-lasting impacts of a technical parole violation from two years ago. I am therefore keenly aware of the harmful practices of over-policing people on parole, which is why I am advocating for parole reform in New York with the Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice, A Little Piece of Light, Unchained, the Robin Hood Foundation, and the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO).

New York’s broken parole system must be reformed. People already facing enormous barriers to reentry must be supported, not policed and over-paroled. Individuals, families, and communities must not be devastated in the name of public safety.

Thankfully, the Legislature has taken a step in the right direction. Legislation (S.1144-A - Benjamin / A.5576-A - Souffrant-Forrest) known as the Less Is More Act, will reduce the number of people incarcerated statewide by restricting the use of incarceration for technical parole violations. But the process cannot begin until the bill is made active by the governor’s signature. I urge Governor Cuomo to sign this bill as soon as possible. Let’s make #LessisMoreNY reality and build safer communities.

***

Yamirca Vazquez is a resident of the Bronx, New York, and a member of CEO’s Participant Advocate Council (PAC) leadership program. She is pursuing a career in advocacy.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Lost Our Siblings to Solitary Confinement; This Torture Must End Now

Mayor de Blasio at Rikers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

June is Torture Awareness Month and it is also the month we both lost our siblings — Kalief Browder and Layleen Polanco — because of the torture of solitary confinement. No other family should ever have to go through the pain and torment our baby brother and baby sister suffered and we continue to suffer. Political leaders from New York City to Washington, D.C. have repeatedly invoked Kalief’s and Layleen’s names to promise to end solitary confinement. Now is the time they must live up to their promises.

Kalief was a 16-year-old child when he was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack. He was held on Rikers Island for three years pre-trial before all charges were dismissed. Kalief was locked in solitary confinement for two of those years. As the world came to learn, the torture he experienced in solitary and jail was too much and he died by suicide after his release on June 6, 2015.

Layleen also should never have been incarcerated, let alone in solitary confinement. Against medical professional recommendations, Layleen was locked in solitary because of who she was as a transgender woman. She was in a unit that was supposed to be an alternative to solitary, but she was locked in a cell most of the day in what was simply solitary by another name. She only lasted in this unit nine days before she died on June 7, 2019, and on the day she died she had been locked in her cell for only two to three hours.

As a result of the massive public outcry over their deaths, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio invoked both Kalief’s and Layleen’s names and promised a year ago to “end solitary confinement altogether” in New York City. Despite this promise, the actual rules recently adopted by the city’s jails oversight body, the Board of Correction, are smoke and mirrors and will continue solitary and just call it by another name.

While falsely touted as an end to solitary confinement, under these rules people will be locked alone in a cage 23 or more hours a day. There is no other name for this horrific treatment than solitary confinement, and the negative impacts will be the same, including immense suffering, devastating physical and mental harm, social deterioration, self-mutilation, and death. Not only will this system fail to fulfill the mayor’s promise to fully end solitary, it will be in direct violation of state law, following the recent enactment of the HALT Solitary Confinement Act.

Because the mayor failed to live up to his promise, the New York City Council must act now to finally and fully end solitary confinement in New York City jails. City Council Speaker Corey Johnson has called for fully ending solitary confinement and ensuring that all people in city jails have access to at least 14 hours out-of-cell per day, including at least seven hours of out-of-cell congregate programming and activities with other people. The City Council’s Criminal Justice Committee Chair Keith Powers and numerous City Council members have also urged a complete end to solitary, as have other leading New York City political leaders, including Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and Comptroller Scott Stringer. We can wait no longer — it is long past time for the City Council to enact legislation banning solitary confinement once and for all.

But this torturous practice must also be banned in states and localities across the country, as well as in federal custody. President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris both promised to end solitary confinement during their presidential campaigns, as did other leading Democratic presidential candidates, including Senators Warren and Sanders. A federal Anti-Solitary Taskforce recently released a blueprint for how the President and Congress can fulfill these campaign promises and end solitary confinement in all federal prisons and detention centers while also incentivizing states and localities to do the same. The President and Congress must act now to enact the recommendations of this Blueprint immediately.

We are already marking six years since Kalief died and two years since Layleen died. From New York City to the federal government, for all of those political leaders who have ever invoked Kalief’s or Layleen’s name or called for an end to solitary confinement, you must finally act now to stop this torturous and deadly practice.

***

Melania Brown is an activist and the sister of the late Layleen Polanco. Akeem Browder is the founder of the Kalief Browder Foundation and brother of the late Kalief Browder. On Twitter @melaniabrown11 & @AkeemBrowderNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Mayor de Blasio: Where's the Full School Reopening Plan?

Mayor de Blasio at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

I’m writing this on June 25—the last day of the 2020-2021 school year.

And while we know next school year will start on September 13, there's so much we still don't know.

There are some factors—vaccination rate, CDC guidelines—that are holding up some of the details, but the lack of a clear plan and clear communication from Mayor de Blasio and the New York City Department of Education now promises some amount of chaos two months from now. And for those of us who remember the chaotic August of 2020, that brings back nightmares.

We know the city is promising a return to five-day-a-week in-person schooling—yet many parents still ask, "Is that real?" Because we've seen how quickly the city and DOE have changed their minds before. Last year, the start of school was pushed back multiple times. Opt-in periods for remote students changed several times. School closure guidelines were in flux. The promises of remote options for next year for the families not yet confident about in-person schooling were reversed suddenly. And in all of these cases, principals and educators learned the news at the same time as parents and the public—often via Twitter or at the mayor’s press briefing.

Since February, many of us have been sounding the alarm: A pledge is not a plan—and if we got to the end of this school year without a clear plan for the fall, informed by diverse stakeholders and backed by sufficient resources, it would mean trouble, and an inequitable fall reopening. Schools with more resources, parents who can raise funds, and greater digital literacy and linguistic access among their communities will be more confident about their return. And schools that are under-resourced and overcrowded—often serving communities of color—will be left wondering how the new school year is safe, resourced, and better than a return to pre-pandemic "normalcy" that already wasn't serving many students.

Many parents don't know what time their kids' school days will start or end (it was within 24 hours before the end of the school year that we learned the school day would restore the hour that was cut from it this year). Many parents have been raising alarms about whether schools will have after-school programs and many after-school providers have been waiting on clarity about excessive fees that spiked during the pandemic—decisions that could have been made while parents and administrators were all still in the school year together, before summer break disrupted the ability to communicate and collaborate around such issues.

Principals don't know how many students they can have in a classroom, so teachers don't know how many students they'll be teaching—so they leave for their well-deserved vacation with the nagging thought that they’ll be racing to prep new classes in the days before schools reopen. And principals aren't sure if they'll need more classrooms than they have which means any efforts to find more usable space will be hectic and uneven in September.

The city has pledged to hire social workers for every school—will they fulfill that in time? What is the ratio of social workers to students, or is it social workers per school? How about nurses and guidance counselors?

Thanks to the federal and state governments, the city has unprecedented funds—but hasn't been clear how it will use them to reduce class sizes, increase small cohort learning, or fulfill IEPs and other individual teacher-student opportunities.

I get that mask mandates (which should go away, in my opinion but we should defer to public health experts) and status of mandatory vaccinations for teachers and students (which should be in-line with other vaccination requirements as soon as we are beyond "emergency authorization") will be based on guidance the state and city do not yet have.

But right now, we're all left guessing on those pieces and many more. And when we're not given a clear vision from the city, schools and parent communities with resources form their own vision, and others are often left waiting and uncertain. Some families who could afford to leave the city may stay away; others who chose parochial schools will remain out of the public school system; many others may simply choose not to send their kids back until it’s clearer what their schools look like, causing low attendance as schools reopen in September

We've lived this story before: A summer of uncertainty, guesswork, rumors, changing reports. This spring—when parents and guardians regularly received paper updates in kids' backpacks and more folks might be able to attend meetings with teachers and administrators—would have been a good time to hear parents' concerns and address them.

Instead, it will be another summer of uncertainty, where we hope for the best, but prepare for chaos, to the extent that’s possible.

City leaders know there's no real reopening of our city without schools being back in action—safely, equitably, with real resources and with schedules that work for students, teachers, and parents.

The time to pull those stakeholders together was these past few months. Now as teachers and students head into summer, principals will work overtime, teachers won't know what to prep, parents will keep guessing and gossipping...and students will be at risk of going into a third consecutive school year where nothing is routine.

As a child development specialist said to me, the best thing parents can do this summer is find something their kids care about and help them learn it -- whether it's a craft or memorizing baseball statistics. Don't worry about "learning loss" or summer worksheets. Help them remember they can learn and can love to learn.

That's what I want to be focused on this summer—but somehow it seems clear many of us will spend part of our summer breaks working with principals and teachers to try to make sense of class sizes, funding questions, school hours, IEPs, after-school programming, and so much more before the fall.

***

Justin Krebs is a parent of three elementary school students in Brooklyn and a parent leader at his own school and in the community school district Presidents Council. These perspectives are his own and do not represent the Parents Association or Presidents Council. On Twitter @justinmkrebs.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Community Hospitals are a Lifeline for New Yorkers. Now They Need Their Own Rescue

Local health care is key (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

When COVID-19 struck 15 months ago, where did those who became infected and seriously ill go? To their nearest hospital.

Hospitals quickly became inundated with patients, and healthcare workers worked around the clock to save tens of thousands of lives. ICU beds filled up, and there was heavy demand on a limited number of ventilators.

While all hospitals were impacted, it was New York’s most vulnerable communities – and the hospitals that serve them – that were hit the hardest. These “safety net” hospitals provide essential care to lower-income and rural communities throughout the state. Without them, many New Yorkers would be forced to go much further to get the medical help they needed.

Now these safety net hospitals need a safety net of their own. Financial struggles were a way of life for them long before the pandemic, and every week was a fight to keep their doors open. After all, these hospitals serve the most underserved New Yorkers, including those who are underinsured or have no insurance at all. Covid simply exacerbated what was already a serious problem and has created an existential threat for many of these hospitals.

Despite the critical role our safety net hospitals play in our communities, they receive little outside funding and are underpaid by Medicaid and Medicare. This chronic underfunding creates financial stress, making it difficult for facilities to make ends meet. It is not a stretch to say that most of these hospitals are in serious danger of closing their doors for good.

While safety hospitals struggle, Governor Andrew Cuomo and the State Legislature have allocated $250 million in state funding (the Distressed Provider Assistance Account) for “financially distressed” health-care institutions “that are critical safety-net providers as determined by the state.” This annual funding was included in the state budget but has not yet been spent. New York is sitting on critically important funding that could be a temporary lifeline. The state must begin allocating this funding immediately.

The services safety net hospitals provide are not just related to the COVID-19 pandemic. These institutions are an essential piece of infrastructure in our communities, whether someone needs maternal care, treatment for a chronic illness, or has an accident and needs access to trauma care. If these hospitals close, the New Yorkers who rely on them will be forced to travel longer distances, potentially complicating an already dangerous situation.

What’s more, these hospitals provide good-paying jobs to the medical professionals in their communities. Without them, patients who desperately need care will suffer, as will those medical professionals who suddenly find themselves out of a job. It is no understatement that hospitals truly are a linchpin for communities throughout the state. Yet, they are edging closer to financial catastrophe.

Critical funding cannot wait any longer. The $250 million that New York has allocated for safety net hospitals needs to be released as soon as possible to help keep them afloat. And going forward, more must be done to ensure that safety net hospitals keep their doors open and continue providing critical services to the New Yorkers who rely on them the most.

***

Jamilah Lasalle is a co-founder of Bait-ul Jamaat – House of Community, a community organization in Staten Island focused on various programs, educational series and advocacy support to the underserved. On Twitter @cprmuslimah & @baituljamaat.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

It’s Time for a Full-Year Legislative Calendar in Albany

In the State Senate (photo: NY Senate Media Services)

While Joe Manchin and Mitch McConnell compete to see who can block the most policy down in Washington DC, here in New York State our Democratic majorities in the State Senate and Assembly are proving that the government can be good. And that governing can actually solve problems.

Earlier this month, Albany’s 2021 legislative session came to a close and legislators should be proud for having made progress on a host of fundamental issues impacting millions of New Yorkers. The legislature raised $4.3 billion in new progressive revenue to fund major investments in public education and to fuel economic relief in the wake of COVID-19. We saw the historic passage of a first-in-the-nation excluded workers fund for New Yorkers who were denied federal relief. And we saw the long overdue legalization of marijuana, the passage of a host of new voting reforms to make it easier and more secure to vote, new regulations to rein in the gun crisis, and a halt to prolonged solitary confinement in our prisons. And this list is far from exhaustive.

Despite all this progress, Albany’s session coming to a close for the year on June 10 inevitably leads to a few fundamental questions. What didn’t get accomplished? And why does the session end at all? Especially with six months to go in the calendar year.

Let’s start with the second question given it clearly impacts the first. It’s true that in many states across the country, state elected officials work as a part time legislature. But here in New York, electeds are full-time employees. It’s also true that our state electeds do more than just legislate. They represent their communities and through constituent services, help solve locally relevant and deeply personal challenges for their constituents. But as seen in the list above, it’s the legislation that gives taxpayers the biggest bang for their bucks. In other words, we elect them to legislate.

And an arbitrary six-month session in New York is holding us back. Moving to a full-year legislative calendar with ample recesses to allow for critical in-district work would unlock massive productivity in Albany. While you certainly can’t look to Congress for great examples of productivity these days thanks to the Jim Crow filibuster and a GOP that’s primary goal is to prove government fundamentally doesn’t work, we should look to their calendar as the model for New York’s legislature. Or to California. California’s state legislature is paid a full-time salary just like New York’s and they work a full calendar year. Simply put, we need our full-time state elected officials to, well, work full-time.

And this isn’t just about creating more time to pass policy. It’s also about removing one of the most frustrating tools in our elected officials’ toolbox that puts a pause on progress. The June end of session deadline acts as an unnecessary and misused “cliff” year over year to block or to slow down important policies. “We just didn’t have the time to get it done” is a phrase we have become all too used to hearing from the middle of June through the end of the year. So this brings us to the first of the questions raised above. What didn’t pass this year?

Let’s take the climate crisis to start. There is no denying that every day we delay action on climate, the more likely it is our planet will be uninhabitable to our youngest generations. Back in 2019, the New York state legislature passed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), a nation leading bill that set aggressive and necessary emission reduction targets for the state. But without further legislation to enact the guardrails, programs, and investments to achieve those targets, the CLCPA is just a promise. And promises won’t solve the climate crisis. This year, the Climate and Community Investment Act (CCIA) — which would raise $15 billion per year from corporate polluters and use it to create good, green jobs, invest in frontline communities, and build a renewable economy for New York State — was the legislature’s best opportunity to turn that promise into action. And yet it didn’t pass. In fact, it didn’t even get a vote.

So I guess it’s better luck next session? In the face of an existential crisis, our plan is to take a break for six months?

And make no mistake, this is just one of many examples where real issues go unresolved for months because of the legislative calendar.

For example: Despite being prioritized in the State Senate, five bills supported by the Sexual Harassment Working Group and the Adult Survivors Act, which would give victims a one-year look-back period to seek justice through civil cases, stalled in the Assembly. Assembly leadership used the clock-running-out excuse to justify the failure to pass these meaningful policies.

Last year, when in the face of a global pandemic that was wreaking havoc on our communities, and disproportionately so on Black and brown New Yorkers, the legislature was quiet from July through December. It’s true, many state legislators were working tirelessly in their communities supporting mutual aid and other constituent services, but their mighty power of policy was left totally unused.

To be clear, it’s not to say these issues are easy to solve. It would be crazy to suggest that legislators have an easy job or that massive legislation like the CCIA doesn’t take time to get right. But that’s exactly the point. There should be no “end of session rush.” Moving to a congressional style, full-year legislative session is better for all involved. Except for the bad actors who want the government to do less or fail more. But New Yorkers continue to show up at the polls to elect better officials each year. And better electeds with more time to legislate will surely bring us better outcomes.

It’s time for a full-year legislative calendar in Albany.

***

Ricky Silver is a co-lead organizer of Empire State Indivisible. On Twitter @es_indivisible.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

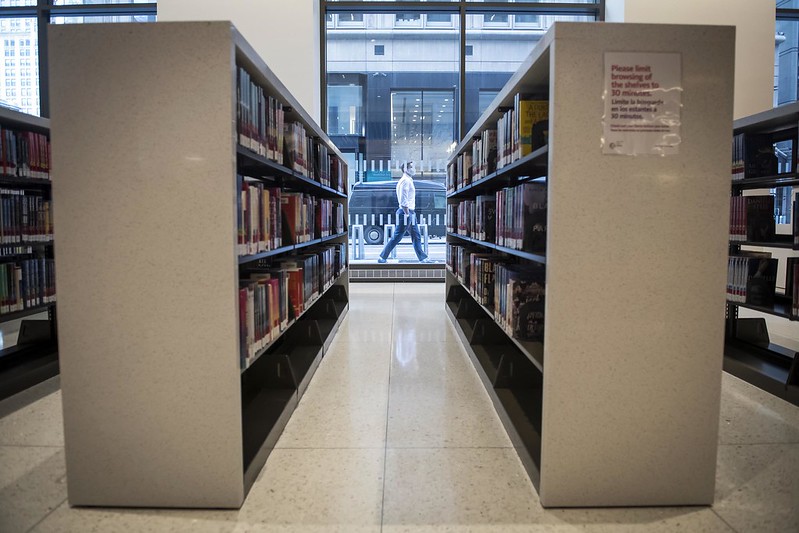

Searching For The Soul of New York: Part I, Literature

Reading New York (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Another school year has passed, the most unusual I can remember. Forced into remote learning by the pandemic, I never actually met any of my students. All I could see were twenty-four curious and anxious faces in small squares across the computer screen. They were there, nevertheless, fully engaged in our journey through New York City history, politics, and government, trying to get a better grip on the city that has been a destination for generations in pursuit of the American Dream.

My Hunter College students bring their own distinct life experiences to our conversations: immigrant, migrant, and native born; Black, brown and white; LBGTQ and not; often challenged economically, rarely privileged. They know New York; they are New York. This is CUNY.

So where might we begin this conversation? Is New York a place or an idea? A destination or an illusion? Does it have a special meaning or purpose? Or is it different things to different people? How does this complex metropolis add up? Does this creature called Gotham have a soul? If so, is it a kind and generous soul that cares for those who are struggling? Or has it a mean and competitive disposition, accepting the harsh notion that only the “fittest” will survive?

All were relevant questions as the city approached one of the most consequential elections in history. Might the outcome of that election tell us something about the soul of New York? Whether its instincts are kinder or meaner?

Before digging into the usual academic material, we began our journey by taking a literary route. New York has drawn the attention of many great writers. Through their special gifts they see things more keenly than the rest of us do, often sooner, and then explain them in ways that become memorable.

We began with Italo Calvino. Calvino (1972) draws pictures with words. He presents the idea of the city in multiple dimensions: as physical structures composed of bricks and mortar, as webs of intricate relationships among people, as storehouses of traditions and memories that carry us forward. Each individual, he reminds us, is only a temporary visitor. While one might hope to influence the direction it takes, the city is a complex organism that has an ever-changing mind and a momentum of its own. How humbling!

Writing in 1968, Joan Didion recalls life as a twenty-two-year-old arriving from California in a city of endless possibility, certain that “something extraordinary would happen,” seeming confident it would happen to her. Full of youthful energy, she is determined to engage the city all on her own, without reaching out to her father, who would surely mail her a check to help out when things got tough. Junot Diaz (2000) never would have contemplated doing that with his dad. The elder Diaz had arrived in Nuova York from the Dominican Republic only to discover that he could not afford to live here, settling instead in a Section 8 apartment in New Jersey, taking on “crap jobs” to eke out a meager living for his family. When college-educated Junot arrived at the age of twenty-six, he had no choice but to take on the city, whose skyline looked like “science fiction,” with only his own limited resources.

An upbeat E.B. White (1949) insisted that it is the “settlers” who give New York its passion, for “each embraces New York with the intense excitement of first love, each absorbs New York with the fresh eyes of an adventurer.” He goes on: “The city is like poetry: it compresses all life, all races and breeds into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines.” White described city neighborhoods, with their grocery stores, saloons, and barbershops as “self-sufficient” communities that give meaning to daily life, cocoons of comfort that shelter one from the cold anonymity of a big city existence. Perhaps he had never met the likes of a Diaz.

Nor a Jean Kwok (2012), who tells the story of a Chinese immigrant mother who spends long days working in a sweatshop as she unsuccessfully struggles to navigate New York’s cultural landscape for her talented daughter. The more her daughter assimilates through the world of dance, the more she distances herself from her loving mother. Can there be a bigger price to pay to become a full-fledged New Yorker? Such pain is out of sight for those who have never made that long immigrant passage.

John Steinbeck (1943) recalls two entries into the city. The first time here, after graduating from Stanford, he made decent money “wheeling cement” in a construction job he found through a family contact before another relative got him a spot on a local newspaper covering stories in Brooklyn and Queens. Journalism didn’t pan out for him. He knew little about newspaper writing and was fired. After his girlfriend dumped him for a banker, he left the “cold and heartless” city returning to California a defeated young man. As he put it, the city had “beat the pants off me.”

Steinbeck’s “second assault on New York” was “different but just as ridiculous as the first.” He had just won a Pulitzer Prize for The Grapes of Wrath and was under contract with Paramount Pictures for Tortilla Flat. He was now living in an Upper East Side townhouse with a private garden. As he got to know the local butcher, news dealer, and liquor man, “Everything fell into place.” His neighborhood became his village, just as White imagined, and things that might have annoyed him the first time around suddenly became part of New York’s charm.

James Baldwin (1960) also recalls the role of storekeepers in the Harlem of his childhood. Those who survived economically extended credit to their customers when people had no money – not that the grocers had much of a choice. Rather than a source of comfort, Baldwin writes with bitterness about his segregated community where residents felt trapped. He describes the “hideous projects” as “colorless, bleak, high and revolting.” For him, they “provide proof of how thoroughly the white world despises” their Black residents. No signs of privilege here. No family with money or connections. As he put it, being Black, gay, and poor, he had hit the “trifecta.” Baldwin writes with conviction and does not resort to hyperbole because he knows it is not needed. He recounts incidences of police violence and the animosity between citizens and officers as if he were writing today.

Baldwin’s fellow Harlem resident, Langston Hughes (1951), foresaw how the tension would eventually explode “like a raisin in the sun.” In the mid-1960s that collective frustration exploded with rioting in cities throughout the country, as it did last summer in less violent forms after the murder of George Floyd.

Were these authors all writing about the same city? Well, yes and no. They all lived in New York, but in very different places. While writing at different points in time, their observations are timeless. New York is full of conflicts, tensions, and inequities. Depending on which piece of it is yours, life in New York can be an adventure or a struggle. But, which piece of it reveals the true soul of the city?

Well versed in the wisdom of Jane Jacobs, many of my students find the soul of the city on the neighborhood sidewalks where people interact. They will tell you that the physical city, with its corporate offices, luxury high rises, and dilapidated walk-ups all reveal the essence of New York. They are well aware of the contradictions. They want to believe that kinder instincts will eventually govern, but are not sure that will happen.

In search of more answers, we turned our attention to politics as an indication of the instincts that can prevail. Over the years, New York City has had some formidable personalities to assume the role as its chief executive. At different points in time they have represented a collective spirit of the city, along with its anxieties and aspirations – or at least the sentiment of those who vote or partake in its voluble political life. That is where the priorities are set. That is where decisions are made regarding who wins and who loses.

This is part one of a two-part reflection. Read part two, on politics, leadership and New York City mayors, here.

***

Joseph P. Viteritti is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College. His more recent books on New York include, The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York and Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York and the American Dream.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Searching For The Soul of New York: Part II, Politics and Leadership

Mayors Dinkins, Koch, Bloomberg (photo: Kristen Artz/City Council)

This is part two of a two-part reflection. Read part one, on searching for New York's soul in literature, here.

By most informed estimates, Fiorello La Guardia stands out as the most admired mayor in the history of New York. That, in itself, tells us something about what New Yorkers expect of their leaders and their city. La Guardia is associated with the progressive ideal that society, through government, has a moral obligation to take care of people who are most in need, people like those who appear in the literature of Diaz, Baldwin, and Kwok.

He carried his message to Washington, and was among those who persuaded President Franklin Roosevelt to launch a New Deal that would rescue the country from a devastating Depression by building infrastructure, public housing, and an ambitious social safety net. That partnership between La Guardia and Roosevelt became a defining formula of progressive governance, holding that the federal government has a crucial role to play in equipping cities and states to meet the needs of their most vulnerable constituents.

That generous instinct was evident in New York before the New Deal. As far back as the 1920s, Governor Al Smith and Mayor Jimmy Walker invested in public works to produce jobs and created public housing to provide subsidized apartments for working people. But the other side of New York that James Baldwin wrote about was also evident then. During La Guardia's tenure, NYCHA consciously chose to segregate housing. The Little Flower was caught off guard in 1935 when rioting broke out in Harlem to protest racism, discrimination, police brutality, and inadequate services. Even in its finest moment, New York progressivism was compromised on issues of race and class.

Progressivism — or mainstream liberalism, as it was called then — would stay on a moderate and steady course beyond the middle of the twentieth century. Mayor Robert Wagner, son of the New Deal Senator, built schools, hospitals and more housing. He breathed life into the municipal labor movement by granting collective bargaining rights to public employees and recognizing their unions. Like La Guardia, Wagner also channeled a limited amount of patronage to Black political leaders. But his gestures on race would prove inadequate. As demands for Black Power replaced the more moderate language of civil rights leaders, a quickened momentum for change outpaced the gradualism of mainstream liberal Democrats whose political base was dependent on white ethnic coalitions.

Mayor John Lindsay embraced an egalitarian and compassionate agenda more aggressively that any of his predecessors. His support of neighborhood government accelerated the political incorporation of Black and Puerto Rican activists. He was the first chief executive to openly oppose discrimination against women and gays. He capitalized on President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs that provided social services to people suffering from poverty. When federal funding to cities became diverted to the Vietnam War and New York’s economy began to buckle under pressure from declining revenue and increasing costs, Lindsay and the inclusive, compassionate liberalism he stood for became a target of a growing conservative backlash. Locally, even newly empowered municipal unions, whose workers advanced progressive demands on economic issues, would occasionally push back when asked to make concessions to Lindsay’s racial agenda.

The fiscal crisis of 1975 that brought the city to the brink of bankruptcy was a major turning point. A spirit of generosity gave way to an emphasis on austerity. Major service cuts and layoffs fell most severely on the most vulnerable people, who were disproportionately Black and Puerto Rican. Mayor Ed Koch epitomized the transition as New York transformed itself from a kinder to a meaner city.

On the one hand, Koch had initiated the most ambitious housing program since the depression; on the other, he was capable of inflammatory rhetoric that fanned the flames of racial animosity. Violent crime reached historic levels. Even David Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor, could not resist demands for more police protection. Crime did dramatically drop under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, but in the process a disproportionate number of Black and Latino men were put in jail.

Michael Bloomberg continued Giuliani’s aggressive approach to policing with his controversial “stop and frisk” policy that was found racially discriminatory by a federal court. The billionaire mayor represented a new form of liberalism, or as some would call it, “neoliberalism.” As a philanthropist and mayor, he supported issues like same sex marriage, gun control, and environmental protection – the roots of which could be traced back to the Lindsay administration. Yet, Bloomberg’s embrace of New York as a “luxury item” betrayed assumptions that took root during the fiscal crisis, which held that New York’s survival would depend on attracting wealth and rewarding privilege.

Retention deals filled with tax breaks and other financial incentives for corporations reached new heights of absurdity. Bloomberg also rezoned one-third of the city to make it ripe for development. As a result, many neighborhoods that once provided comfortable homes for working class and poorer people started to disappear as casualties of a gentrification process that displaced long-time residents in favor of those with more wealth.

Bill de Blasio’s election in 2013 marked another turning point. Running on a “Tale of Two Cities” platform, de Blasio was the candidate in 2013 most willing and able to directly confront the Bloomberg legacy. Not since John Lindsay had any candidate taken on the issue of police brutality so directly. More importantly, he opened up a conversation in New York on economic injustice that would distinguish the progressivism of the new century from the old liberalism of the past, and demonstrated that it could win votes. In the meantime, national Democrats like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren had begun a campaign that would eventually move their party off the middle ground it had occupied since the Clinton administration, whose policies contributed to the most severe polarization of wealth in the free world.

Governor Andrew Cuomo did not go along with de Blasio’s plan to finance his signature pre-kindergarten program by raising taxes on the rich, or any of the mayor’s redistributive tax proposals for that matter. De Blasio did ensure an end to “stop and frisk” abuses and worked with a more progressive City Council to pass a number of pro-labor initiatives involving a “living wage” and expanded health benefits.

Although nowhere near peak levels of the 1980s, violent crime is on the rise again in New York and it has taken center stage in the 2021 primary election battle. Tensions with the police remain high in communities of color.

City politics finds itself in a rather odd place these days. Donald Trump is out of the White House and Joe Biden, a seasoned moderate, seems to be taking cues on economic policy from progressives like Senators Sanders and Warren, who Democrats once wrote off as too extreme for comfort. The country may be on the verge of having a new New Deal.

In the meantime, crime and economic development (rebranded as economic recovery) seemed to take over the conversation among candidates for mayor in New York. Little has been heard about the economic justice issues that once helped elect de Blasio. There has been discussion about the urgent need for more affordable housing; but half the eight leading Democrats running for mayor did not support increasing taxes on rich people who have gotten richer during the pandemic.

Did New York ever recuperate from the shock of the 1975 fiscal crisis? Has it lost its progressive soul? When the question is posed to me by my students, my first reaction is to say “No.” If they push me further, I admit I could not continue doing what I do if I did not keep telling myself that. When I think about it further, I return to the essay we read together by John Lewis, published days before his passing, where he explained how the recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations gave him faith in their generation and persuaded him that they can “Redeem the Soul of the Nation.” I hope he is right.

***

Joseph P. Viteritti is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College. His more recent books on New York include, The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York and Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York and the American Dream.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ranked-Choice Voting Won Out — Let's Not Blow It with Premature Tabulations

Voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

After a once-in-a-century pandemic, concerns about rising gun crime, debates about usage of our streets, and perennial conflict over integration of our schools and neighborhoods, the 2021 mayoral primary cycle's final day centered less on why we were voting than on the mechanics of how we'd be casting our ballots.

Watching Kathryn Garcia and Andrew Yang team up to campaign jointly over the home stretch, current vote leader Eric Adams baselessly compared the ranked-choice motivated alliance to a poll tax and said the instant-runoff system approved by New York voters three-to-one was effectively abetting voter suppression. Adams also continued to hedge about whether he'd even abide by the results of a ranked-choice tabulation. While in many instances he has been unequivocal about abiding by the outcome, he has at other times betrayed reluctance, including commenting that “no one is gonna steal the election from me,” bringing to mind Trump's Big Lie about his own loss and the resulting capital insurrection.

Fear-mongering about ranked-choice voting depressing turnout or confusing voters—from Adams and allies including City Council Members Laurie Cumbo and Daneek Miller, among others—didn’t bear out. Turnout was high, reporters profiled numerous voters expressing confidence about how to rank their preferences, and candidates are properly directing their supporters to wait until every vote is counted before declaring victory or acknowledging defeat.

The high voter turnout and ranking enthusiasm are great news, but it's not too late for us to blow it.

Judging by the Board of Elections' announced plans for ballot-counting and tabulation, they’re about to add confusion by running interim tabulations of ranked-choice results on incomplete sets of ballots every week until all ballots are processed. This means candidate rankings will shift unpredictably until certification.

In doing so, the Board of Elections runs the risk of telegraphing an inaccurate outcome that could indeed undermine confidence in the real one—especially if the changes impact Eric Adams’ final tally, and he uses those shifts to attack the system he and his allies so often question. It’s not just Adams who might find fodder in inaccurate tabulations: any of the twelve losing campaigns may do so in whiplashed tabulation results.

This unforced error is avoidable if New York changes course and decides to act more like Maine—the state whose ballot access efforts I led in 2020. Maine has been a national leader on successful usage of ranked-choice voting, and it waits until all votes are received and ready before performing its ranked-choice “instant runoffs.”

It would be a pity to muck the election up now: so far, RCV has been a huge success.

With over 120,000 Democratic absentee ballots yet to count, turnout appears to have surged to its highest levels since 1989. The New York Post ran a comprehensive feature about how intuitive and inclusionary voters found the process of ranking their preferred candidates. Reviews of Campaign Finance Board reports show a surprising paucity of attack ads. And, almost assuredly, this system will be the one under which New York elects a new mayor who is female, Black, or both—and a City Council with more than the aspirational 21 women members targeted by the "21 in ‘21" campaign.

Judging by the voters profiled across the city, New Yorkers' experience with RCV has made them feel more bought into the outcomes of their races and more interested in learning the details of candidates' platforms; these are the very benefits that have led Maine to nation-leading turnout and recommitment to the system on a second statewide ballot referendum.

Now it's time for voters to wait for the results.

Some commentators are mistakenly blaming Board of Elections mismanagement or RCV for the fact that final results remain a couple of weeks away, and the media could be doing a better job explaining that the cause of any further delay isn't running tabulations but processing absentee ballots.

That process is slow for good reason: voter-friendly rules allow receipt of ballots by a week after Election Day and include a window during which voters may "cure" certain ballot defects. The Legislature has already ensured this process will be faster in future elections by passing a law that will allow earlier processing of absentees received before election day.

If New Yorkers now just have to sit tight to let absentee ballots be processed, and then for RCV tabulations to be run, what could there possibly be to worry about?

Well, the problem is that the Board of Elections doesn't plan to do these steps serially, but to run tabulations on subsets of ballots while still processing others. This plan will do nothing but confuse voters about how the allocation of those votes will work out.

According to the current plan, beginning on Tuesday, June 29, the BOE will start modeling RCV tabulations—eliminating the lowest first-rank vote-getter from contention, then allocating their ballots to the second-place choices on those ballots, and continuing those "instant runoffs" until there are just two candidates left and showing a winner—on whatever subset of ballots they happen to have ready each week.

That won't be all the ballots, and it will be skewed heavily to early and primary day ballots to the exclusion of absentees. Absentees might be systematically different from the rest of the ballots (for example, if they’re more likely to be cast by older voters or by Manhattanites, or both).

FairVote, a nonpartisan organization that promotes use of RCV, notes that these "unofficial" tabulations have been done elsewhere—such as San Francisco—and says they're similar to unofficial vote counts from election night.

However, the logic of how election night vote totals will change as more ballots get counted is extremely straightforward. Eric Adams has 31.7% of the roughly 800,000 early and primary day first-place votes, Maya Wiley has 22.2%, and Karthryn Garcia has 19.5%. As well over 120,000 absentees get counted, those numbers will shift. Still, we know that each candidate’s current first-place vote numbers can only go up as more ballots get counted.

In spite of this clarity, even releasing early and primary day vote totals while absentees are coming in presents challenges to voters’ understanding of the results. For example, the simple "blue shift" of changes to the top-line numbers from election night in 2020—when mailed ballots favored Joe Biden over Donald Trump, showing a flip in states like Pennsylvania as they were counted—was enough to underpin the Big Lie.

RCV instant runoffs extend those normal shifts with an unimaginable butterfly effect, because the final order in which candidates finish determines the order in which their votes get reallocated. Running RCV tabulations before all ballots are in can thus have distressing consequences.

Imagine if the reallocation of lower-placing candidates’ ballots shifts who ends up in the final two with Eric Adams. Kathryn Garcia's voters, largely in Manhattan and influenced by the New York Times editorial board, may overwhelmingly prefer Wiley to Adams—giving Wiley a shot to win if she’s the last candidate standing with the Brooklyn borough president. Conversely, many Wiley voters may have ranked Adams, the other top-tier Black candidate, after her, meaning that Garcia wouldn't benefit as much from that reallocation. As more absentees get processed and included in forthcoming RCV tabulations, we might flip from one of those scenarios to the other.

These scenarios are conjectures. Still, what’s certain is that what we see in “unofficial” tabulations may not give us an accurate preview of the final result. Unlike primary night results reflecting the first-place top-lines, having processed 90% of the ballots doesn't mean RCV tabulations will be 90% representative of the final result. Indeed, they might be diametrically opposed to it.

What will happen if the multiple premature RCV tabulations show major variability in the final result, given that they will reflect results of runoffs that only include a subset of the electorate?

RCV is a fantastic system that leads to more representative, more inclusive outcomes. There is no reason to undermine New York voters' experience of it through the release of pointless interim tabulations. Instead, we should run RCV tabulations all at once after all ballots are received and cured, as Maine does.

Democracy advocates know that a slow and steady count is the best bulwark against claims of election fraud. When we're so close to the finish line, the BOE should be wise enough to hold out to deliver its own. New Yorkers will be patient if the BOE communicates that comprehensive results are worth waiting for.

***

Ryder Kessler, a former executive board member of Manhattan’s Community Board 2, served as the Maine Democratic Party’s 2020 Voter Protection Director for Joe Biden and down-ballot Democrats. On Twitter @ryderkessler.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Close the Credibility Gap for New York City Schoolchildren

Kids in school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The full in-person public school re-opening won’t be a return to normal for the New York City school children who have suffered most from 16 months of covid turbulence, exacerbated by histories of systemic and structural racism. Their outlook on life has fundamentally changed.

As Schools Chancellor Meisha Ross Porter has acknowledged, we need more social workers in schools, lifting students’ voices. But unless we as social workers and educators can also shift our approach to meet their realities, we will lose a pivotal opportunity to re-engage a significant majority of our young people.

Perhaps the question is: should we return to “normal” at all – or do we want to build a more equitable school system that fulfills the promise of opportunity for all our children?

New York City’s school system enrolls 41% Latino and 26% Black students—and these students have lost parents or caregivers at twice the rate of Asian or white children. The insecurities are profound: 23% of those Latino and Black children are at risk of entering foster or kinship care and 50% of living in or falling into poverty.

Organizations such as ours that provide trauma-informed counseling and mental health services in public schools have stayed connected to our students remotely when schools closed in March 2020 and since then in person as necessary throughout on-and-off schedules and turbulent re-openings. We have seen an influx of new referrals and increased hardships, underscoring the mental health crisis emerging from the pandemic.

Now in the precious weeks and months ahead, we must accelerate our outreach with culturally-competent summer programs and ongoing mental health supports that empower students to candidly express themselves. This will give us a true understanding of the troubling emotions, experiences, and outlooks that our most vulnerable children share and endure.

This will necessitate reframing our approach to social-emotional learning (SEL), a core element of social work. Traditionally this process aims to help children understand their emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy, and make responsible decisions.

The shortcoming of this approach is that too often those goals are set by others without considering the context in which each child comes to school.

For a generation of children coping with the everyday realities of COVID-19 devastation, exacerbated financial hardship, and systemic racism, SEL can feel like a parallel universe to their own experience.

When children come to school hungry, how can we expect them to think about others, let alone engage with the material and participate in class? When a middle school student follows stories of police brutality toward Black men, should he really be expected to set aside his heartbreak and anger to learn about the American Revolution? Are we asking children to frame their behaviors to conform to a reality they don’t experience?

Our work is grounded in neuroscience showing that the stresses of financial, food or housing insecurity can become toxic and inhibit children’s abilities to learn and socialize. Establishing trust as a caring adult is proven to buffer children from factors that are out of their control.

The outdated expectation that young people can rise up “by their bootstraps” on a clearly uneven playing field needs to be replaced by an equity strategy. Right now, our credibility as a society is at stake as it never has been. Everyone should be watching to ensure we provide the right educational and social service supports for children as we emerge from the pandemic and open schools fully.

In the year ahead, we should make sure our schools feel nurturing and safe to children and families. The schools must meet children where they are, and build trust with school communities. We especially need social workers who have lived through the pandemic and have experienced systemic racism to work with and for the communities they serve, culturally-responsive teaching, and materials to which children can relate. Finally, practitioners of Social Emotional Learning must consider modifying their practice to consider children’s lived experiences and the context of the school environment in which our students are often forced to navigate.

This is not only a formula for healing, but also an opportunity to empower children to use their emotions and their voices to re-imagine their futures.

This fall, when students fill New York’s public schools, let’s make sure their hearts and minds are in class too.

***

Travis Rodgers is Chief Equity and Strategy Officer at Partnership with Children.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Remembering Herb Sturz: Pioneering Social Entrepreneur

Herb Sturz, left, and Jonathan Lippman, one of the authors

Herb Sturz, one of the original social entrepreneurs, died this month.

Herb was equal parts bright-eyed idealist and sharp-eyed power broker. All of the obituaries and tributes that will follow in the days to come will no doubt detail his remarkable resume.

Herb was a man of many hats. The founder of the modern bail reform movement. The spark behind the creation of numerous nonprofit organizations, including the Vera Institute of Justice. Deputy Mayor and City Planning Commissioner under Mayor Ed Koch. Member of the New York Times editorial board. Real estate developer. Philanthropist working for the Open Society Foundations. And many more.

Has anyone ever touched so many different professions? Herb knew the power players in a wide variety of fields.

Like many movers and shakers, Herb’s success was built, in part, on the strength of his social network. But Herb was much more than a man with a golden rolodex.

We had the pleasure of working with Herb on various criminal justice reform projects over the past three decades. In unguarded moments, we would often seek to ascertain the secret of Herb’s success. He was obviously a man of intellect and ambition. But the truth is that New York City is full of people like that. Herb had something else.

Over the years, we came to realize that Herb’s two superpowers were creativity and humility. He was a man of a thousand ideas. Not all of them were great, but his batting average was better than anyone else we can think of.

Crucially, his imagination was paired with a willingness to work behind the scenes and let others receive the glory. Harry Truman is credited with saying “It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.” Herb was the living embodiment of this insight. This was a key factor in his ability to convince powerful people to run with his ideas.

Herb’s creativity and humility were much in evidence in the last great fight of his career: the battle to close the notorious jail complex on Rikers Island.

It was Herb’s idea to create a blue-ribbon commission to study the idea of closing Rikers back in 2016. This wasn’t exactly a new idea for Herb – he had tried to get rid of Rikers before, back in the Koch administration, without success. This time around, he went to Mayor Bill de Blasio and then-New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and asked them to authorize a commission.

Mark-Viverito launched the commission with great fanfare at her state of the city address. We were in the audience watching with Herb that day – he had also asked each of us to be part of the Commission.

At that point, closing Rikers Island seemed like a progressive fever dream rather than a real possibility. There was, to be sure, a vibrant grassroots movement, led by formerly-incarcerated activists, arguing for closure and building public support. But most public officials were cool to the idea, and the Mayor questioned whether closing Rikers was logistically feasible. In normal times, this lack of institutional support would spell doom for any new criminal justice reform.

Given this reality, why did we sign on to Herb’s scheme? Because Herb was the one doing the asking. Herb was willing to put his time and effort and reputation on the line. That immediately convinced us that the fight might be winnable.

Having brought the team together, Herb then made his next crucial move: he faded to the background, allowing us to step forward to organize the commission and lead it forward. He knew better than to micro-manage, but he was always available with advice whenever asked.

Five years later, the effort to close Rikers Island is still ongoing. But enormous progress has been made. The Mayor and the City Council have both endorsed a plan to shutter the inhumane jails. It will remain for the next Mayor to carry this plan to fruition.

However things turn out, we are grateful that Herb asked us to participate in his plan to close Rikers Island. It was, and is, an audacious effort to make the world a better place on behalf of a population that is often voiceless in policy debates. We hope the next generation of Herb Sturzs is waiting in the wings to take up the battle.

***

Jonathan Lippman is a former chief judge of New York State and of counsel at Latham & Watkins LLP. Greg Berman is the former director of the Center for Court Innovation. They are both members of the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, which Lippman chairs.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Gender Violence is on the Manhattan DA Ballot

Voters voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

New Yorkers are choosing the next Manhattan District Attorney, who will profoundly shape prosecutions of gender-based violent crimes like sexual assault, domestic violence, trafficking, stalking, and hate crimes targeting women of color. It is essential that the next Manhattan DA combat the scourge of mass incarceration of non-violent offenders, and at the same time combat the under-prosecution of violent and predatory gender-based crimes. In the U.S., 49 out of 50 rape cases do not result in jail time for the perpetrator. We need the next Manhattan DA to lead in a better direction.

Yet some of the candidates have taken positions that would leave victims of gender-based violence even less protected than they are now. Here are just a few examples for Manhattan Democratic voters to consider.

Domestic violence

One survey asked if candidates would dismiss charges any time there are cross-complaints (two people accuse each other of violence) and the parties say they do not want to go forward with a criminal case. But false counter-allegations are a classic abuser tactic to terrify victims into dropping charges. Good prosecutors scrutinize cross complaints carefully, proceed with caution when a victim proposes to drop charges, and assess victim intimidation and lethality risk.

A blanket promise to dismiss cross complaints would nullify the victim’s access to criminal justice protection whenever a batterer strategically files a retaliatory charge. Candidates who promised to dismiss charges when there are cross-complaints included Tahanie Aboushi, Alvin Bragg, Diana Florence, Eliza Orlins, and Dan Quart. The candidates who answered “No” to this question were Tali Farhadian Weinstein and Lucy Lang. The eighth Democratic candidate, Liz Crotty, did not participate in the survey.

Sentencing

Multiple candidates in the race agreed that they would “never seek more than the minimum sentence.” Even for progressives like me who want to see incarceration reduced for many offenses, this pledge is extremely problematic when applied to violent crimes. If a serial child molester charged with multiple counts of sexual abuse in the first degree has no prior conviction (which many serial abusers—think Larry Nasser—do not), the minimum sentence is probation. Yet probation would be wildly irresponsible in such a case.

For countless cases of rape, domestic abuse, and other forms of violence, the minimum sentence would likewise be totally inappropriate. Survivors need prosecutors to tailor sentencing requests to the merits of each case, not adopt a one-size-fits-all policy. Candidates who agreed they would “never seek more than the minimum sentence” included Tahanie Aboushi, Alvin Bragg, Diana Florence, Lucy Lang, Eliza Orlins, and Dan Quart. The candidate who answered “No” to this question was Tali Farhadian Weinstein. Crotty again did not participate.

Resources

Some candidates pledged to cut the resources of the Manhattan DA office by 50%. Yet prosecutions of gender-based violence are labor intensive and are already under-resourced. We need the next DA to redistribute precious resources so that prosecutions of gender-based violence receive the investigative work, the expert witnesses, the forensic testing, the technology support, the trauma-informed approaches, and the prosecutor time and attention they need.

Candidates who agreed to cut the office’s resources by 50% included Tahanie Aboushi and Eliza Orlins. Candidates who answered “No” to this question were Alvin Bragg, Tali Farhadian Weinstein, Diana Florence, Lucy Lang, and Dan Quart. Crotty did not participate.

Arrest policy

Candidates were asked if they support a “mandatory arrest” policy for felony domestic violence. These are cases in which the abuser has caused serious physical injury, used a weapon, or violated a stay-away order of protection – truly dangerous situations. The policy instructs police officers to arrest assailants, not try then and there to “reconcile” the parties. It was enacted to stop officers from telling batterers to ‘take a walk around the block’ to cool off, leaving victims in danger. Candidates who opposed the arrest policy were Tahanie Aboushi, Alvin Bragg, Eliza Orlins, and Dan Quart. Candidates who supported the arrest policy were Liz Crotty, Tali Farhadian Weinstein, and Diana Florence.

The next Manhattan DA needs a bold, smart plan for combating gender-based violence. A report by Reform the Sex Crimes Unit evaluates and links to the candidates’ platforms; voters can assess the thoughtfulness and detail of each candidate’s approach. New Yorkers need the next Manhattan DA to show the world that we can reduce incarceration for non-violent crimes and combat the abuses of the criminal justice system, while at the same time protecting survivors of domestic violence and increasing the prosecution rates for rape. Let’s keep survivors of gender-based violence at the center as we build the New York City we want.

***

Jane Manning is an attorney and advocate for survivors of sexual assault.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.