The Right Side of Rikers History

Melissa Mark-Viverito, the author (photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

For decades, Rikers Island has served as a clear illustration of our nation’s willingness to turn a blind eye in the face of injustice. Home to decades of violence, corruption, and cruelty, the continued operation of Rikers Island jails has been a striking reminder that our justice system is anything but just.

Activists, grassroots organizers, impacted individuals, elected officials, and many other New Yorkers have been demanding the closure of Rikers jails for decades, but their pleas have often fallen on deaf ears. Now, the New York City Council is on the verge of casting a vote that could get us one big step closer to ending the injustice of Rikers once and for all.

As activists and advocates, it has been a long, treacherous process getting to this point. But we have now reluctantly handed over the torch to our elected officials and urge them to understand that they too have a moral obligation to do everything in their power to close down Rikers. Our hard work and our fight has gotten us this far, but we need our representatives to stand with us and get us one step closer to eliminating a system that has deprived people of their dignity, respect, and basic human rights.

When I initiated the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform (The Lippman Commission), I tasked its members with determining if and how Rikers could be closed. The commission was made up of policymakers, researchers, system actors, and directly impacted individuals like Julio Medina, the Executive Director of Exodus Transitional Community, a preventative, reentry, and advocacy organization located in East Harlem.

Like Julio, many survivors of Rikers and their loved ones exposed the jails’ horrendous conditions and inhumane treatment. Survivors recounted not just the horrors they lived while in Rikers, but the devastating life-long impact their experience had on them and their families.

Stories like that of Kalief Browder, an African-American man from the Bronx who was unjustly arrested and held at Rikers for three years – two of them spent in solitary confinement – have been told in many variations over and over again. By sharing narratives, those closest to the problem became instrumental in devising solutions to overhaul and reinvent a deeply broken system.

The Commission’s report, alongside the momentum, leadership, and advocacy of those who have been directly impacted, forced Mayor de Blasio to put forth the current plan under consideration, calling for the closure of the Rikers jails and the reduction of jails in New York City from twelve to four.

The Lippman Commission has been committed to transparency in its process, allowing for planning and advocacy to happen in full view of an initially-skeptical public. In 2016, there were dozens of public meetings in all five boroughs, each inviting people from across the city to provide input. The #CLOSErikers campaign, led by directly impacted individuals, created a collaborative community process that produced a robust set of transformative demands, known as the #buildCOMMUNITIES platform. The public was also given the opportunity to critique and demand amendments to the borough-based jails plan through local Neighborhood Advisory Councils, town hall meetings, and the rigorous public review process of the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure.

To hear opposition forces now claiming that too few opportunities for public input have been offered is downright wrong, and an affront to the openness and outwardly engaging process that has taken place.

The reason for advocates’ high standard is obvious: they know that we only have one chance to get this right — not just because it has taken decades to get here, but also because failure is fatal. Faltering now in the face of the opposition's NIMBY-ism, racism, and false representations would mean that Rikers will probably remain open for generations to come, creating immeasurable cost.

Today, I proudly stand with Julio Medina and many, many others as we urge City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and all New York City Council members to approve this plan. We are closer to our goal than ever before. Let this be the Council that can say that they stood on the right side of history by voting to close down the Rikers Island jails and create a stronger, safer, and better New York City.

***

Melissa Mark-Viverito is a former Speaker of the City Council and currently a candidate for Congress in New York’s 15th Congressional District. On Twitter @MMViverito.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Counting Votes So They Really Count

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

I am usually in agreement with the analysis and opinions of Bruce Gyory, a prolific pundit and consultant who writes on New York City and State government and political affairs.

But I must disagree with his op-ed in the Daily News last week, urging New York City voters to reject city charter revision proposal #1 on the fall ballot, which would create a ranked-choice voting process for party primary elections for City Council, borough president, and citywide positions.

The shortcomings of the current primary election system cry out for correction. Bruce doesn’t deny these inadequacies but he doesn’t present an alternative proposal. The unintended consequences that Bruce predicts are speculative. I believe ranked-choice voting will be an improvement, and it should be adopted by voters as they cast their ballots through the early voting period (October 26-November 3) or on Election Day, November 5.

According to our current city election law, we have two methods for choosing the winners of party primaries, one for citywide positions and one for borough-wide and City Council seats. For citywide positions, if no candidate wins more than 40% of the vote in a primary the two candidates with the most votes then participate in a separate run-off election. In other races, whomever gets the most votes wins, even if it is a crowded field, as Democratic primaries often are in New York City, and no one hits even 40%.

With ranked-choice voting, there would be no separate run-off elections because voters would select not only who they want to win, but also their second, third, fourth, and fifth choices at the time of the initial primary. If no one wins 50% or more outright, the votes for the candidate with the lowest first-place vote total would be reallocated to those voters’ second choices, and so on until someone gathers enough votes to exceed 50% of the updated vote total.

Bruce states that RCV is untested. In fact, it has been in use in San Francisco and Minneapolis/St. Paul for years and was recently adopted in Maine, so the software needed to adopt it is readily available and we’ve seen some positive initial results. He worries that some voters’ voices will be stifled, particularly those of people of color. On the contrary, ranked-choice voting will empower more voters to express their preferences and ensure that the winner of a primary – which in New York City is often tantamount to the entire election – is preferred by a majority of those who come out to vote.

Sadly most registered voters don’t vote in primaries and far fewer take the trouble to come out to vote in runoffs. In the runoff for public advocate in 2013 only 7% of eligible voters, or a little more than 200,000 people, voted and in effect chose the public advocate. In a city where 2.8 million Democrats were registered to vote, having 200,000 decide the outcome is not representative democracy. While not ideal, the original primary at least saw about 530,000 votes cast for public advocate candidates.

Bruce worries that polls will become too important because people will make choices based on which candidates seem most viable. Even if that turns out to be true (do most voters really pay attention to polls?) it would still be better than having only a tiny number of the most organized and motivated voters select elected leaders for the rest of us. There are also typically no or next to no polls for every office other than mayor. With ranked-choice voting everyone who votes in the primary can be assured that their vote will help determine the winner and I predict that it will lead to higher turnouts: people now unmotivated to vote because they prefer a candidate they think is unlikely to win can make their stand by voting for their candidate as a first choice, and then selecting others as alternatives. Ranked-choice voting is also likely to push candidates to campaign in front of more voters in hopes of appealing to as many as possible to be their first or second choice.

Of course, given my background as a fiscal watchdog, it is no surprise that part of my discontent with the current system is that it is expensive and wasteful. The 2013 public advocate runoff cost taxpayers $10.4 million to deploy voting machines and poll workers that were used by only 200,000 voters citywide. This means taxpayers spent $51.00 per vote, and that doesn’t include campaign expenditures by the candidates, partially covered by our public campaign finance dollars. Not to mention that the cost far surpasses the annual budget for the office of public advocate. I am sure each of the readers of this column can think of a more useful and cost effective way to spend $10 million in city revenue.

Ranked-choice voting is not the solution to all the problems with administration of our elections and we need further reforms at the state level, e.g. same-day and/or automatic registration and combined federal and state primaries. But city-level ranked-choice voting is a common sense, cost-saving reform that will make candidate selection in primaries more participatory and democratic, and I urge all registered voters to come out on November 5 (or sooner, via early voting that starts October 26) and vote yes for ballot proposal #1.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Why I’m Voting Yes to Close Rikers and Build Humane New Jails

Council Member Costa Constantinides, the author (photo: Emil Cohen/City Council)

Nothing in New York City’s or our country’s history says we’re good at running jails.

For hundreds of years, we have cast detainees away to far-flung islands. Out of sight, out of mind. Mostly black and brown men. Overwhelmingly, without having even been convicted of a crime.

So, the recent skepticism to build a jail in the heart of my beloved Queens is justifiable. After countless meetings with criminal justice advocates, many among them previously jailed in Rikers Island’s houses of horrors, it’s clear the borough-based plan now before the City Council is the best option New York has.

A decision like this isn’t arrived at easily. I am ultimately voting “yes” this week because the perfect cannot be the enemy of the good while thousands of people are stripped of their human rights, confined in decrepit, asbestos-riddled jails far from their attorneys, families, and communities.

The alternative would be to walk away now with no plan to close the Rikers Island jails.

A once-in-a-generation opportunity to shut down the jails for good, in as little as five years, would vanish. The rare consensus among academics, the legal community, and victims of this broken system, which ensures people paying their debt to society are rehabilitated and prepared to re-enter civil society, will have been in vain. As a legislator, as a New Yorker, and as a human being, I cannot let this happen. The Lippman Commission rightly called the 80-plus years of jailing people on Rikers a stain on our city’s history.

The stories from Rikers remind us why the jails there must close and why we must do better in the future. Sadly, it took Kalief Browder’s suicide after three maddening years in solitary confinement, a punishment that was hideously disproportional to the crime for which he was accused, for many of us to listen.

Now, we’ve heard from Vidal Guzman, who recently pointed out that “Just because someone has left Rikers, doesn’t mean that Rikers has left them.” Kandra Clark, who spent four months in the infamous women’s facility, has spoken about the emotional torture of “the male correctional officers who would watch me go to the bathroom through the window in my cell door each night.” Dr. Homer Venters, the former chief medical officer for Correctional Health Services, recently went public about the toxic culture within the jails as well as what this physical and mental abuse looked like up close.

A “no” vote punts this to the next City Council, guaranteeing this inhumane status quo lives on for the time being. Instead, the City Council vote on Thursday can pave the way for more humane facilities. Is incarcerating any person the ideal? No. But, as former detainee Marco Barrios said earlier this year, the borough-based facilities “will not fix all the problems by themselves, but they can provide important progress.”

This week, the Council will vote to build smaller, safer detention centers for violent-crime suspects and anyone else who spends any time in jail in New York City; to make it easier for the loved ones and attorneys of all those detained to visit them; and to create a system focused on rehabilitation of those swept up in the system.

New York City will invest in programs within the detention centers to break people free from this vicious cycle. And, our state government in Albany has been chipping away at the system that essentially makes being too poor to afford bail a crime. Previous reforms have already put us on a strong pace to shrink the city’s jail population from the current 7,000 to the necessary 4,000 that guarantees the permanent closure of the Rikers jails.

Life is full of grey areas. The harsh reality is that some people commit heinous crimes and must be kept from the public. We, as a society, owe that to every child who’s had to hide under a bed, taking low, quiet breaths while an abusive parent bangs on the locked apartment door. Rape victims deserve to walk the streets without fear their attacker is out in public.

But no longer will New York City’s jails function like a factory that takes in teenagers on a marijuana possession charge and pumps out hardened repeat offenders.

The rest is on us as policy-makers. I believe the city should invest in elements of the #CloseRikers coalition’s #BuildCommunities platform. This money must go into black and brown neighborhoods that traditionally have seen few city investments beyond more police cruisers.

The coalition has common sense asks: supportive housing, job training, access to physical and mental healthcare, educational investment, partnerships with community groups, as well as neighborhood conflict de-escalation and alternatives to incarceration. These investments should not be a one-shot either, and I will continue to fight for these things well beyond my tenure in the City Council.

Community leaders, criminal justice advocates, and former Rikers detainees believe the plan the Council votes on this week will work. I trust them. And I trust my colleagues in the City Council and elsewhere in city government to follow through on the promises we’re making. I will be among those making sure that we do.

Tomorrow, the next day, and every day after this vote we have to break the stigmas around the formerly incarcerated. Remember the Bryan Stevenson mantra: “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.” The City of New York must apply this same logic to itself. The mistakes of our predecessors shouldn’t prevent us from making the right decision for the future.

Rikers Island can be part of that future if the city uses the vacated land to get dirty infrastructure out of the same communities broken apart by the criminal justice system. These are the power plants, sewage facilities, and garbage stations that give people asthma, make them miss school, and saw their opportunity ladder in half. Voting to close Rikers today means we can give our kids a healthier tomorrow.

***

City Council Member Costa Constantinides represents District 22, which includes parts of Queens and the Bronx, including Rikers Island. He is the chair of the Committee on Environmental Protection. On Twitter @Costa4NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

I’ve Seen It First-Hand Over Decades and Know: Rikers Cannot Be Redeemed

On Rikers Island (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

The narrow bridge to Rikers Island still puts a knot in my stomach. In the late 1980s, I spent two years behind bars in one of the eight active jails on Rikers. Back then, crossing that bridge meant disappearing from society and entering a world defined by violence and inhumanity.

Little has changed. These days, I visit Rikers regularly as vice chair of the Board of Correction, the independent oversight body for New York City jails, and as executive vice president of the Fortune Society, an organization that helps people succeed when they come home from jail and prison.

Rikers still sends one message to everyone who crosses that bridge, no matter if you’re a correction officer, incarcerated person, or visitor: you are worthless. People feel like animals, caged and mistreated. They react accordingly.

During my first year at Rikers, this combustible mix exploded into a riot led by people brought down from upstate prisons for legal proceedings in the city. In theory, these men should have been happy to be closer to their families. But to visit Rikers, their loved ones still had to spend all day traveling to the island for just an hour together—as my father once did when I was jailed on Rikers. I hated to see the effect on him so much that I asked him not to come back.

The men from the state prisons experienced the same pain. The anger they felt from mistreatment by correction officers and the brutal physical conditions of Rikers drove them to barricade themselves in their housing unit and erupt in the mess hall.

Thirty years later, violence still permeates Rikers, where hints of disrespect are met with force. The jails remain inaccessible to families, lawyers, and other much-needed connections to the outside world. The conditions are still dehumanizing. During the July heatwave, I toured the jail where I was held so many years ago. The cinder blocks and metal worked like an oven. Officers patrolled in shirts drenched with sweat. A few cheap fans pushed around hot air, never reaching the people sweltering in their cells or stationed at their posts.

The vast majority of people at Rikers are awaiting trial, as I was. Almost all of them are people of color. Every day, nearly 800 people must be bussed to and from courts in the boroughs at cost of $41 million a year.

Moving around inside the poorly-designed jails is also difficult, requiring an officer escort down hallways that can stretch hundreds of yards. Too often, incarcerated people do not make it to medical appointments, family visits, recreation, commissary, and court. Cases are delayed, anger rises, and health suffers.

We can change this. In April 2017, after years of pressure, Mayor Bill de Blasio committed to shutting down the Rikers jails, reducing the number of people locked up by half or more, and holding this smaller jail population in facilities near the borough courthouses.

Since then, the number of people in jail has dropped by thousands. Our city remains as safe as ever, demonstrating we do not need mass incarceration to achieve safety.

This week, the City Council will vote whether to authorize four redesigned borough jails that will enable the permanent closure of the eight jails on Rikers and the jail barge moored to Hunts Point.

This plan is a once-in-a-generation chance to close Rikers and replace it with something far better, and far smaller. But no one should underestimate how hard it is to close an institution like Rikers.

It will require more changes to police and district attorney practices. It will take continued reforms in Albany, like passing the Less Is More Act to fix New York State’s broken parole system.

It will also require approval of the smaller borough system under consideration by the City Council. The initial designs for these facilities would promote safety and facilitate re-entry. Located much closer to courthouses and public transit, they would speed up cases and increase access for attorneys, family members, and others. They would be more accountable to oversight, leading to better conditions.

In final negotiations, the Council can improve the current plan by securing major community investments, so people never end up in jail in the first place. But this plan has to pass or we will be stuck with the horrors of Rikers for decades to come. We cannot allow the quest for the perfect to stop us from doing what is right.

Since I came home to the Bronx, I have dedicated myself to helping others succeed. The sprawling, unmanageable, and violent jails on Rikers undermine that goal and our communities. Let’s end this disgraceful chapter in our history.

***

Stanley Richards is Executive Vice President at The Fortune Society, a member of the Independent Commission on Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, and a member of the Justice Implementation Task Force. On Twitter @Stan_Fortune of @thefortunesoc & @MoreJustNYC

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Governor's Signature is Next Step in Protecting New York Children from Toxic Toys

(Dreamstime: Photo 3882847 © Jose Manuel Gelpi Diaz - Dreamstime.com)

Perhaps few items in society hold the same universal delight as children’s products. They are an important part of children’s wellbeing and development and can remind all of us of simple joys of childhood. We expect products designed specifically for children to be safe and free from chemicals that could cause harm.

Nobody wants their child to play with a toy containing alarmingly high levels of lead, cadmium, or mercury. However, there are many toys and products on the market today that do indeed contain chemicals that are hazardous to children’s health. Media reports of product recalls of children’s jewelry tainted with lead and arsenic, colored chalk contaminated with mercury, and baby soaps containing a chemical called 1,4 dioxane raise serious questions as to how manufacturers have been able to get these products into the market in the first place.

These products have been able to enter our state because of gaps in our regulation. Our regulations in New York have struggled to keep pace with the thousands of new combinations of materials and manufacturing processes involved in making children’s toys and products.

The good news is that New York has taken significant steps to remedy the issue through the state Legislature, with the new Child Safe Products Act, which passed in April 2019. By signing it into law on or around National Children’s Environmental Health Day, Friday October 11, Governor Andrew Cuomo could prevent further unnecessary harm to children on his watch.

The Child Safe Products Act, once signed, is poised to provide protections to keep toxic products out of the marketplace for all children. It would prevent the sale or resale of items containing the most dangerous chemicals — particularly important where consumers have less money for costlier toxic-free alternatives.

Low price and discount retailers that are commonplace in New York’s less affluent communities have been found to sell items containing very high levels of so-called “chemicals of concern.”

For example, a 2015 study by the Campaign for Healthier Solutions and HealthyStuff.org tested products commonly sold at dollar stores, like toys and jewelry for children, and found alarmingly high levels of lead, mercury, and cadmium. The new law would take a measured approach to regulating chemicals in products developed for children and includes a comprehensive list of chemicals that are currently known to have adverse effects on human health.

The Child Safe Products Act would also provide clear directives for each member of the supply chain – from the manufacturer to the seller. Manufacturers would be required to report to the state the chemicals included on the list that are found in their products. The state would in turn provide this information to an interstate chemical clearinghouse. Retailers would be notified which items they are forbidden to sell, due to their toxicity, and they would be held accountable for selling such items, prompting greater scrutiny in their buying processes and supply-chain management.

Intergenerational principles urge us to be mindful of our responsibility to ensure the health and safety of the next generation. This applies to all aspects of a child’s environment – where they live, learn and play. Governor Cuomo has lent his support to several environmental causes. Signing this act would demonstrate our joint commitment to future generations of New Yorkers and solidify our place as leaders in protecting children’s environmental health. Other states like Maine, California and Washington have similar policy mandates.

Let’s ensure that the next generation of New York’s children comes to associate products designed for them with happiness. Governor Cuomo, please sign the Child Safe Products Act into law and affirm New York’s commitment to a greener, more sustainable future for everyone.

***

Christine Appah, Senior Staff Attorney for Environmental Justice at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, a member of the JustGreen Partnership that supported passage of the Child Safe Products Act. On Twitter @NYLPI.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Surveillance and the City: Facing Up to Facial Recognition

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

Sometimes City Hall politics can be surreal; too much spin can give you a case of political vertigo. But this week was remarkable even by the standards of the de Blasio administration, with talking points that felt like messages from a parallel universe. Time and again, we heard lofty statements about a city committed to protecting its residents’ privacy, a city sadly bearing no resemblance to our own.

It started when the national facial recognition debate came to the City Council chambers. Months after cities like San Francisco fully banned facial recognition, New York City lawmakers introduced a trio of modest proposals that just scratch the surface of our municipal black mirror, and held a hearing on them.

One bill requires notices in stores when they use biometric surveillance like facial recognition. A second bill would require all buildings to register any biometric surveillance with the city. And a third bill guarantees New Yorkers the right to a metal key, even when their building uses key fobs or biometrics. These bills are not perfect, and they’re certainly not the full facial recognition ban that more and more cities are passing, but they’re a start.

Predictably, the Mayor’s Office claimed to “support the bills’ intent,” before pivoting to the litany of reasons why as laws they would be too much of an “operational challenge” or better suited to another agency. The metal key requirement was the only item to receive support.

This back and forth would have been utterly unremarkable if not for the constant proclamations of how New York City protects privacy. Countless empty phrases like we “value the privacy and livelihood of all New Yorkers” or “protecting the privacy of New Yorkers is something both the Council and Administration care a lot about.” Sadly, these platitudes hide the reality of New York City today.

The New York I know deployed automated license plate readers, perpetually logging almost every car in the city. It worked with the MTA to deploy the OMNY fare payment system, even as organizations denounced it as a privacy threat to every passenger. And then there are the biometric programs.

Programs like the NYPD’s DNA dragnet, which captures thousands of New Yorkers’ genetic information, including young children. And, of course, the most controversial program of all: the NYPD facial recognition database. This error-prone digital dragnet is used to arrest thousands of New Yorkers, many of them wrongly.

Of course, the administration’s tone shifted as soon as these troubling biometric programs came into the discussion. How many city agencies use facial recognition? “We don’t know.” How long can biometric data be kept? “We don’t know.” When city officials were asked point-blank if the NYPD uses facial recognition, something already reported around the world, the representatives suddenly were at a loss for words.

One program that administration officials were surprisingly eager to talk about was LinkNYC, the Frankenstein creation that’s part billboard, part phone charger, part wi-fi hotspot, and part tracking device. One NYC DoITT official proudly claimed that the LinkNYC privacy policy wouldn’t let the system “collect or store any identifying information.” She went on to assert that the city “specifically prohibited the use of facial recognition,” and included “some of the strongest safeguards in the country.” The privacy advocates in the room were bewildered.

In reality, LinkNYC kiosks—which combine the aesthetics of a 2001 monolith and the Las Vegas strip—have come under intense scrutiny in recent years, following investigations by the Intercept, Gothamist, and others. Despite the administration’s claims, LinkNYC does provide photos to the NYPD facial recognition program in some cases (Link claims to do so only when subpoenaed). Even worse, activists highlighted LinkNYC’s potential power to track New Yorkers by transforming our wi-fi and bluetooth-enabled devices into veritable homing beacons (Link says only when users have opt-ed in via an app). The revelations sparked guerrilla privacy campaigns and widespread calls for LinkNYC’s elimination.

Sadly, the City Hall spin didn’t end with LinkNYC, or at the hearing. This week also saw a remarkable statement on NYPD facial recognition from Commissioner O’Neill himself. When asked about a facial recognition ban, he plunged us back into the mirror universe, claiming “No one is being arrested solely on a facial recognition hit” and calling it an essential tool.

Thanks to researchers at Georgetown and the NYPD’s own data, we know just how misleading a claim that is. At least one NYPD employee openly boasted about facial recognition’s role in arresting more than 2,700 New Yorkers. The commissioner often responds that no one is arrested solely based on facial recognition, but let’s look a little closer.

NYPD officers have included suspects in lineups solely because of facial recognition. In one case, officers texted a witness asking, “Is this the guy…?” and attaching a single photo. In both cases, the NYPD claims that the eyewitness is the reason for the arrest, but decades of false convictions demonstrate that these sorts of suggestive practices can warp witnesses' memories and lead to wrongful convictions.

The reality is thousands of predominantly black and Latinx New Yorkers would never have been arrested without the unreliable and deeply-biased facial recognition system, and I’m terrified to think just how many are innocent.

Part of why New York lags so far behind the rest of the country in reforming biometric surveillance is that the de Blasio administration won’t face the facts. It insists on spinning platitudes about New York being a privacy leader. We’re not. It’s long past time we let this fantasy fade and wake up to the sobering reality of what these Orwellian technologies are already doing to our communities.

***

Albert Fox Cahn is the executive director of The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project at the Urban Justice Center, a New York-based civil rights and privacy organization. He writes the monthly "Surveillance and the City" column for Gotham Gazette. On Twitter @FoxCahn.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Letter to the Editor: Key Points from Our Report on City Storefront Vacancy

(photo: NYC Planning)

To the Editor:

In response to the opinion piece “Our Small Business Crisis is Very Real, and Demands City Action,” (Sept. 25), we want to caution that the tens of thousands of retail businesses in New York City come in all shapes and sizes, and no one solution fits all.

Contrary to the author’s claim, the Department of City Planning’s (DCP’s) Assessing Storefront Vacancy report details and directly links neighborhood vitality and affordability to the challenges that local shop owners face – from ever-evolving consumer tastes, competition from e-commerce, significant regulatory hurdles, changing streetscapes and high rents, particularly on higher-end retail corridors.

From every angle, the DCP report’s findings are clear: first, vacancy rates differ dramatically from neighborhood to neighborhood, and even block to block, and for different reasons; and second, some retail corridors are thriving.

The DCP report reinforces what we have suspected for years: traditionally strong dry-goods retail markets, such as department stores and hardware shops, are the most challenged, while restaurants, entertainment, and experiential retail – services sought after by residents and workers that cannot be replaced by e-commerce – are multiplying. What may be surprising is that brick-and-mortar retail jobs grew by 33% between 2008-2017, with jobs in restaurants, bars, and food stores exploding, gaining 132,000 jobs.

While zoning restrictions may initially sound like good solutions, the DCP report shows that cumbersome regulations hurt small businesses the most. We also know that singling out chain retailers is not a sound solution for a variety of reasons, including because many New York chain stores started out as mom and pops.

What the DCP report highlighted is that there are no easy answers, and that there is not one set of solutions that works for all types of stores and all types of businesses, in every neighborhood.

Sincerely,

Marisa Lago, Director of the Department of City Planning

@NYCPlanning

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Chinatown Advocates Call on Council Member Chin to Make Her Position Clear Ahead of Jails Vote

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

“To be clear is to be kind, to be unclear is to be unkind.” – Brené Brown

On August 2, 2018, I attended a meeting at Chung Pak, the affordable senior housing complex on Baxter Street, where the city presented its plans to build a huge new jail in Chinatown. I and other highly-vetted attendees watched a slideshow of what 80 Centre Street would become after it is converted from the county courthouse and district attorney’s office to a 50-story jail with coffee shops and retail trinket stores on the ground floor. Discussions of adding a Chinese cultural center within the jail were laced throughout all discussions to sweeten an obviously bitter pill, as jails often are.

The city’s plan changed course after vehement community protest. The city eventually stated that it was too expensive to relocate the offices at 80 Centre Street, as if the idea had belonged to them in the first place. They switched sites to 124-125 White Street.

City officials argue a jail is good for communities. Matthew Washington from Borough President Gale Brewer’s office has said in response to concerns, ‘but you already have a jail there.’ This platitude attempts to explain why some believe expanding a jail within the city’s largest carceral footprint outside Rikers Island is not worthy of protest from residents and businesses.

Fourteen months later, after six mayor-controlled “community” meetings, two town halls, one scoping hearing, a site change, and a mayoral visit to Chinatown with a highly-vetted group devoid of true community and media presence, our community still knows virtually nothing about the proposed jail.

When leaders are unclear, uncertainty abounds. That uncertainty leads communities to anger, fear, and anxiety. It’s no wonder why anti-jail posters in Chinatown are appearing in storefronts and family association buildings with City Council Member Margaret Chin’s face splashed across them. When the mayor’s office defends the “ongoing” and “robust” dialogue between the mayor’s office and Chin, it only serves to stoke the flames of discontent because the talks are done in secret. To be unclear with the public is to be unkind.

Chin is capable of making her points clear when she wishes. At a press conference in Brooklyn on January of this year, at the site where three Chinese men were murdered by Arthur Martunovich in his vicious attack with a hammer, Chin exclaimed “Let’s be clear, this was a racial hate crime – plain and simple.”

It’s that clarity that we seek today for our beloved community, yet we remain unfulfilled due to uncertainty. Palpable concern festers in coffee shops and dim sum parlors, in barber shops and hair salons, where the often-asked questions “What has Margaret Chin said? How is she going to vote?” can be heard.

As author Brené Brown points out, a lack of clarity may happen when one does not know how to be truthful. If the truth is deemed too painful to reveal, humans sometimes obscure or mask the truth. Or it’s not shared at all.

A lack of clarity may also be a form of deceit. Why reveal one’s true intentions outright, when obfuscation hides the backroom deals? A lack of clarity may be a result of paralyzing fear. ‘What if they don’t like what I have to say? What if it causes more anger?’

So long as Chinatown is left unclear about Council Member Chin’s upcoming vote on October 17, the community will continue to languish in hellish anxiety. One must ask why a successfully elected representative with such strong Asian-American support could be so unkind to her constituents.

Perhaps a unified reminder from us can encourage her to be clear now. I urge all of Council Member Chin's constituents to reach out to her to raise your concerns and her awareness.

To be clear is to be kind, to be unclear is simply unkind.

***

Jan Lee, co-founder of Neighbors United Below Canal (N.U.B.C.). On Twitter @NUBCanal.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Trump Tells the Truth, Sort of - Poverty & Unemployment Rates Down for People of Color, But Full Story is Complicated

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

President Trump’s nonstop record of false claims (12,000-plus labeled false or misleading as of an August count in the Washington Post) received a brief respite recently when he tweeted that poverty and unemployment rates for black and Hispanic residents of the United States had reached record lows, which PolitiFact and other media outlets acknowledged as accurate.

While it’s true poverty rates for black and Hispanic Americans are down, as you’d expect, Trump still failed to talk about the whole truth.

Here it is: the causes of these improvements have included nine-and-a-half straight years of economic expansion, demographic changes that have brought people of color to 50% or more of the entering-prime-age workforce, and record levels of educational attainment. (Of course, the president did not comment on the continued severe racial and ethnic disparities in American society faced by people and communities of color.)

A closer look at some United States and New York City economic, poverty, and educational attainment data over time helps put the president’s point in the context of the profound racial injustices and disparities that are part of our society.

Snapshot - Recent History of Poverty and Unemployment

The U.S. Census reported recently that the poverty rate for black Americans was 20.8% in 2018, while the poverty rate for Hispanics was 17.6%. Poverty rates for non-Hispanic whites and for Asian-Americans were far lower, and the overall poverty rate for Americans was 11.8%.

Monthly unemployment rates are more fickle than annual averages, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics August 2019 unemployment rates were 5.5% for blacks and 4.2% for Hispanics (yes, they were both record lows, although Hispanics had reached the same point earlier in the year). The unemployment rate was 3.7% overall.

Employment hit bottom in the Great Recession in February 2010 at about 130 million jobs after the U.S. lost 8.7 million jobs over a two-year period; in the next seven years under President Obama the economy gained 16 million jobs, and has gained 5.8 million jobs in two-and-a-half years under President Trump. The U.S. economy gained nearly 22 million jobs over nine-and-a-half years of uninterrupted economic expansion to reach the current unemployment numbers, including the record lows for black and Hispanic Americans.

Most Prime Workers are People of Color

The Washington Post presented the table below in a September article entitled, “For the 1st time, most new working-age hires in the US are people of color.“

In other words, one major reason black and Hispanic Americans are doing better is pure demographics -- they are half the new people getting jobs because they are half the people (along with other people of color) entering the labor force!

U.S. Recessions and Expansions Seriously Impact Poverty

The economic history of recessions and expansions, with increases and decreases in poverty rates, is not new. Below is a look at poverty in the United States from 1959 to 2010. In 1959, 55% of black Americans lived in poverty. The graph does not show it, but poverty for whites in 1959 was 18%.

Following a recession in the early 1990s, President Clinton oversaw an eight-year economic expansion that brought job gains of more than 22 million from 1993 to 2001, about the same as the current national expansion. The poverty rate in the United States in the year before Clinton became president was 14.5%, but much higher for blacks, 33.3%, and for Hispanics, 29.3%, according to U.S Census data.

By 2000, following those eight years of job expansion, the U.S. poverty rate had declined to 11.3%. The black poverty rate declined from 33.3% in 1992 to 22.1% in 2000, only slightly higher than the level just reached in 2018. The poverty rate for Hispanics in 2000 was 21.2%. It took an expansion with 22 million jobs gained to reach the record low black and Hispanic poverty rates under President Clinton, same as it took the 22 million job expansion from 2010 to mid-2019 to reach the recent record low.

A smaller recession occurred in the United States in 2001, followed by lower economic growth. By 2007, the year before the Great Recession, the poverty rate rose to 12.5% overall, and was 24.5% for black Americans and 21.5% for Hispanic Americans. Following the Great Recession of 2008-2009, and an initially limited recovery in 2010, the poverty rate in 2011 reached 15% overall, and the rates were 27.6% for blacks and 25.3% for Hispanics.

As the health of the American economy improved, poverty rates declined again. By the end of President Obama’s second term, in 2016, the overall rate was 12.7%, and poverty rates had declined for blacks to 22.0% and for Hispanics to 19.4%. It took gains of 16 million jobs from 2010 to the beginning of 2017 to bring these poverty reductions.

What About New York City’s Poverty Rate?

New York City’s poverty rate has hovered around 20% of its population for decades, according to a 2011 New York Times article based on census data.

In 1990, the poverty rate was 19.3 %, in 2000 it was 20.1%, it had dropped to 18% by 2007 before the Recession, and it swung back up to 21.2% by 2012. In 2017, the New York City poverty rate was 19.6%, according to the American Community Survey. In 2017, 22.3% of black New Yorkers and 27.3% of Hispanic New Yorkers were living in poverty.

People of Color, Despite Discrimination, Have Achieved Record Educational Attainment

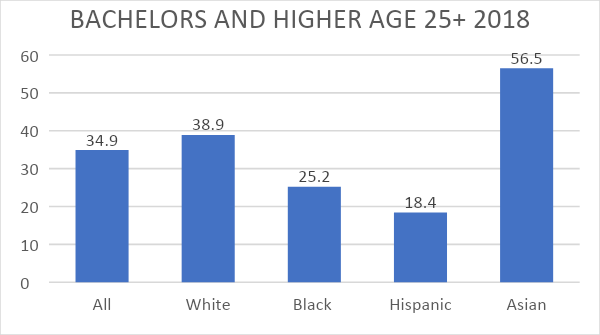

It’s hardly a secret that the American economy has transformed itself into a service and information economy with higher demand for educated workers. People of color in the United States (and New York) have persevered in the challenge to gain skills, despite significant barriers. Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations have achieved record educational attainment, a success correlated with hard work in the face of discrimination that is a record in each and every year, very different than the up and down swings of the economy.

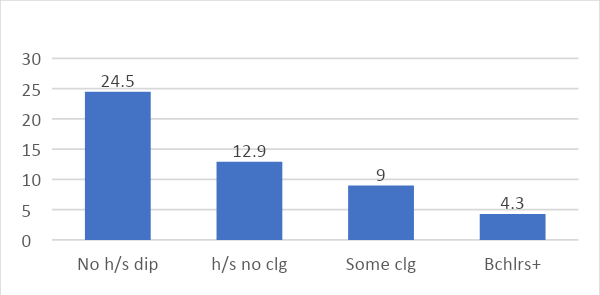

Why focus heavily on educational attainment? Because the correlation between educational attainment and poverty is very strong. Below are the U.S. Census Income and Poverty data on this correlation for 2017 for persons age 25+, with poverty rate by educational attainment levels.

For persons 25+ without high school diplomas, nearly 25% lived in poverty in 2017. For persons 25+ with high school diplomas but no college, 12.9% lived in poverty. For those 25+ with some college, 9%, and for those 25+ with bachelor’s or higher, 4.3%. (In 2018, 16.2% of persons under the age of 18 lived in poverty.)

Across the United States, younger black people, ages 25-29, have achieved near parity with whites in the percentage who have completed high school, according to the Current Population Survey. Younger Hispanics are also achieving much improved high school completion rates, and young Asians have higher high school completion rates than whites.

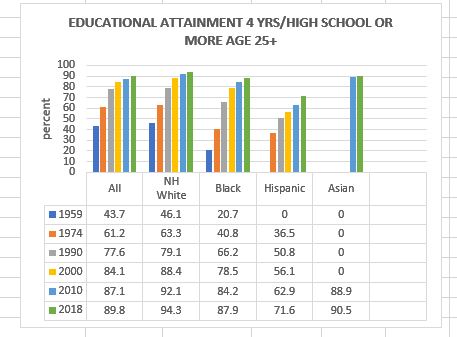

COMPLETED 4 YRS HIGH SCHOOL OR MORE AGE 25-29

Although younger black and Hispanic Americans are closing the gap with whites in high school completions, for the full population over the age of 25 they still suffer from disadvantages compared to the rest of the nation in the attainment of bachelor’s degrees and higher.

The following table on the history of educational attainment shows the long struggle to move forward for American communities of color, along with the extraordinary disadvantages they suffered compared with whites during U.S. history.*,**

*The Census in 1990 and earlier reports whites, not non-Hispanic whites. The zeros reflect that the Census did not report these numbers in those years.

**1974 is the first year Hispanics are reported separately.

In NYC, High School Graduation Rates for Communities of Color Have Improved Dramatically

In New York City, high school graduation rates for black and Hispanic students have improved dramatically over time, like in the rest of the nation. The table below is from the New York City Department of Education for 2018 and provides the graduation rate for an entering 9th grade group, called a cohort, for August of their fourth year of high school. The cohort is the group of students who entered 9th grade in 2014.

What the table above does not show is how many students were still enrolled in school after that summer of their fourth year, but have not yet graduated. It’s important to include the number of students still enrolled because large numbers of students do complete high school after their fourth year.

The 2014 9th grade cohort of black students shows 72.1% graduated by August 2018, but DOE statistics also show that 18.6% of the black students in the 2014 cohort were still enrolled but had not graduated.

Looking at the six-year graduation rate for black students, for the 2012 9th grade cohort, 77.5% had graduated and 5.5% were still in school.

For Hispanic students, 70% of the 2014 9th grade cohort had graduated and 17.9% were still in school. For the 2012 cohort, 74% had graduated and 5.2% were still in school.

Similarly, graduation rates for the New York City school system over the past few decades show enormous improvements. Going back to 1992, only 51% of New York City high school students graduated overall, and those numbers excluded full-time special education students. In 2005 the state government required the city to include special education students in the graduation rates, so the overall rate restarted in 2005 at 46.5% and for general education students was 58.2%.

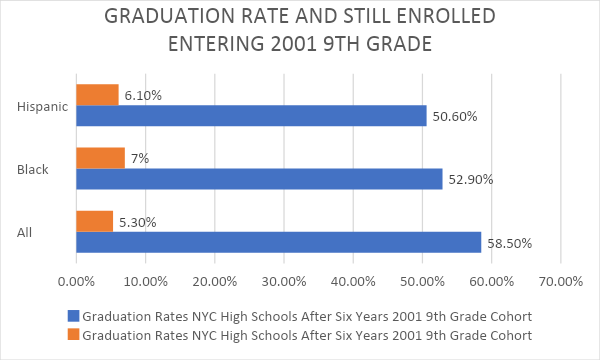

The chart above does not have racial/ethnic breakdowns, but the DOE does have published racial/ethnic data for the 9th grade cohort entering in 2001, including graduation rates for 2005, as well as their six-year graduation rates.

The table below shows the six-year graduation rates, with those still enrolled, for the New York City school system for all students, and black and Hispanic students for the 9th grade cohort that entered in 2001.

For the entering 9th grade cohort that year, about 53% of black students had graduated by their sixth year, and 7% were still in school. For the 2012 cohort, 77.5% of black students had graduated by their sixth year, and 5.5% were still enrolled. For the 2014 cohort, 72.1% of black students had graduated by summer of their fourth year, and 18.6% were still in school.

For the entering 9th grade cohort of 2001, of Hispanic students, 50.6% had graduated by their sixth year, about 6% were still enrolled. For the 2012 9th grade cohort, 74% had graduated and about 5% were still in school. For Hispanic students in the 2014 9th grade cohort, 70% had graduated and 17.9% were still in school.

The numbers for students who had graduated after six years or were still enrolled have improved dramatically between the 2001 entering cohort and the 2012 and 2014 entering cohorts.

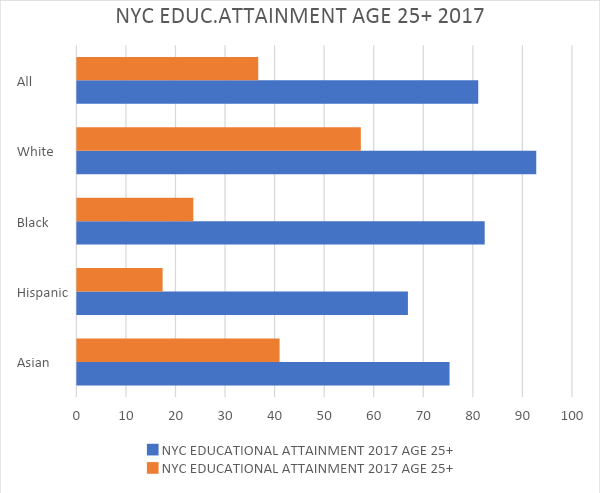

Educational “Achievement Gap” for NYC Students is Narrowing

The New York City Department of Education also reports on the extent to which the “achievement gap” between black, Hispanic, and white students for high school completions is narrowing.

Educational attainment rates for New York City residents age 25 and over continue to show major disparities between whites and the city’s populations of color; 57% of whites have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to about 24% of blacks and 17% of Hispanics. About 93% of whites have completed high school or higher, versus 82% of blacks and 67% of Hispanics.

Across the nation, 39% of whites have college degrees or better, compared to 57% of whites in New York City. About 23.6% of blacks in New York City have college degrees, compared to about 25% nationally. In the city, 17.4% of Hispanics have college degrees or better, compared to 18.4% of Hispanics nationally.

So, while President Trump’s tweet about black and Hispanic populations reaching historically low levels of poverty and unemployment was true, this achievement has nothing to do with advances brought forward by his administration. It’s been a slow and overall steady – but sometimes rocky – climb, which includes almost a decade of straight economic expansion, demographic changes that have brought people of color to 50% or more of the entering prime age workforce, and record educational attainment for black and Hispanic Americans.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Fighting and Dying for Dignity in Prison

(photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Last week, my friend and client Carlos passed away in the custody of the New York State Department of Corrections. His life had been filled with so much suffering and pain, and yet he showed me only friendship and kindness during the three years I was privileged to know him. Known to his friends and family as Carlos, Edgardo Gonzalez was a professional boxer before he was sent away to serve a sentence of 50 years to life after an attempt was made on his life in a South Williamsburg bar and he killed two people.

He had fought Olympic champion Howard Davis at Madison Square Garden in 1977, had a daughter he loved more than life, several brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews, and a mom and dad whom he was so proud to be able to financially support during their lifetimes. He was one of the toughest guys I’d ever met, a Lower East Side legend, but he was warm and patient and always checked in on me during our weekly calls.

Once inside the prison walls, Carlos earned his master’s degree and an impeccable institutional record. He received one disciplinary ticket in 36 years for having an “untidy cell” after he was found with a photograph of his mother on his cell wall. Carlos tried his best to maintain relationships with his family members despite the barriers placed between them, but he was mostly alone and left to grow old in prison.

I met Carlos while attending law school at City University of New York School of Law. Together with two classmates we filed a clemency application on his behalf in 2018, which was never even acknowledged by the Governor’s office or supported by the supposedly progressive elected officials we reached out to. Hundreds of pages and years of dedication to his personal growth were discarded. A cruel and false sense of hope taken from Carlos.

A year later, after 36 years behind bars and a diagnosis of liver failure absolutely brought on by years of medical neglect and the toxic prison environment he’d endured, I requested and was finally granted a medical parole board hearing for Carlos where his release would be considered 15 years ahead of its scheduled date.

At the beginning of August, I sat with Carlos, a 75-year-old man who lost his breath when he said more than a few words, to prepare for a hearing that would unearth decades-old traumas and memories from what seemed like another life to him now. He would be forced to claim full responsibility in a room of ex-cops and prosecutors, people who knew nothing about what incarceration does to a person, a family, a soul, and would diminish all the successes he had earned no thanks to the system that locked him in a cage, a system that tried and finally succeeded at killing him.

After 36 years of solitude and hopelessness, and despite all his physical pain, he found the strength to do this. He opened himself up to an audience who had taken everything from him, the same kind of minds that believed in jail sentences that last entire lifetimes. He found the grace to thank them.

About a week later, Carlos called me while opening the letter that would grant him his release. He said, “Does this mean I’ll be free?” I said yes, soon. He cried and said he wished he wasn’t so sick.

Carlos fought so hard, but before parole would approve his placement in his family’s home, a process that may have taken months or up to a year, he was rushed to a non-prison doctor and hospital where they found his body incurably riddled with cancer. It was too late for any treatment, a doctor said to me while asking that I make decisions about his end of life care. I was also too late and the system too slow, and his hope was once again lost.

Carlos held my hand when I visited him last week and we looked out his hospital window at a view of trees and concrete, prison guards surrounding his bed. He said, “I was so close and now I’m so far.” At the hospital in Westchester, we were less than 30 miles from the neighborhood he grew up in New York City, closer than he’d been in nearly 40 years. He joked with me, at least I think he was joking, saying I should flush his ashes down the toilet when he passed. I said no way, Carlos, your soul will be reunited with your sweet mom and dad in Puerto Rico when you go.

I am heartbroken and angry, and I am in court each day trying to be there and be outraged for my clients who are also fighting for their hope and survival.

I have clients who tell me they’d rather kill themselves than go to jail. It is long past time to abolish jails and prisons, and, as implored by my former professor, urgent and immediate action must be taken to rectify the massive and inhumane sentences handed down to Carlos and thousands of others. Prosecutors and judges must support efforts at resentencing, the Legislature must reform a punitive parole system, and the Governor must grant clemency to countless people languishing in prison.

Prison killed Carlos and despite my pleas the system refused to let him die a free man. He had more than earned that last dignity if you believe such a thing needs to be earned, but he did not get it. Prison guards surrounded him in his final moments, often watching his television at a volume that prevented him from resting and blocking his medical providers’ access to him.

Every day, jails and prisons take lives, and those losses are almost exclusively suffered by communities of color. Prison walls are not built just to keep incarcerated people locked inside, but to keep the rest of us from looking in. We must refuse to accept the lie that prison is about rehabilitation. The only thing these systems of incarceration believe in is taking every last thing, especially hope, from the humans they trap inside.

Prosecutors, judges, police, court officers, prison guards, caseworkers, parole officers, and defense attorneys all participate and are culpable in the process of dehumanizing those inside. Carlos worked for decades to show them who he really was, so much more than a “body” or the worst thing he’d ever done, and he never quit. He died fighting to be free.

Thank you, Carlos, for sharing some of your precious time with me and for teaching me more than I could ever put into words. It was a privilege to sit by your side and bear witness to the end of your life. Your struggle will be remembered, and I will continue to fight, harder than ever, for you.

***

Claire Stottlemyer is a graduate of CUNY School of Law and a lawyer with the Legal Aid Society’s Criminal Defense Practice in Manhattan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Surveillance and the City: IDNYC’s Not-So-Smart Future

(photo: Demetrius Freeman/Mayor's Office)

It’s hard to think that winning your legislative campaign can cause a problem, but when you combine progressive victories with the territorialism of New York politics, you can get disturbing results.

Case in point, this past legislative session was a triumph for the immigrant rights movement across New York State. We enacted the Dream Act, securing in-state tuition for undocumented New Yorkers. We passed the Farmworkers Bill of Rights, closing the antiquated exemptions that left so many immigrant laborers vulnerable to exploitation. And we enacted the Green Light bill, finally securing immigrant New Yorkers the right to a driver’s license. This last bill might have been the biggest triumph for immigrant families, but it was a political setback to one of Mayor de Blasio’s flagship initiatives: IDNYC.

After collaboration by the mayor and the City Council, IDNYC was launched in 2015 as a form of identification for all New Yorkers, irrespective of immigration status. But with undocumented New Yorkers now able to get driver’s licenses and non-driver IDs, justification for the municipal ID program is fading. Rather than concede that IDNYC may have outlived its usefulness, City Hall is trying to add new features in the hope of clinging to relevance.

In what is only the latest IDNYC spectacle, the de Blasio administration wants to add a radio frequency identification (RFID) chip to store everything from financial data to potentially even health records. It’s a change that no one wants or needs, and would put 1.2 million IDNYC cardholders’ privacy at risk.

The proposed RFID chip is a threat to every cardholder, but it particularly endangers the very community IDNYC was supposed to protect: undocumented New Yorkers. It will if the change goes through, but City Council Member Carlos Manchaca -- a leading architect of and advocate for passage of the original IDNYC law -- has introduced a bill to stop the smart chip. His measure would block the payment chip and limit IDNYC cards to only include the information on their face: no health information, no financial information, nothing else.

As Council Member Menchaca and advocates noted, the Trump administration could use the new RFID chip to subpoena information on the 1.2 million New Yorkers using IDNYC. They wouldn’t need a warrant or probable cause, just a letter saying that the information would be helpful.

This nightmare scenario is nothing new. Many of us raised these concerns when IDNYC was first launched. They were dismissed at first, as outlandish. Then, when Donald Trump won the 2016 election, the danger became all too real, and soon the mayor found himself in court, trying to block a GOP effort to turn the municipal ID program into a virtual immigrant registry.

Now we’re raising the alarm again, but the mayor seems dead set on repeating history, moving forward with this disastrous initiative even as immigrant advocates from across New York City say that this program is a mistake. Sadly, this fits the pattern for de Blasio, a mayor who is eager to speak on behalf of immigrant communities, but slow to act.

In 2017, when the city passed sanctuary city legislation, elected officials celebrated two bills to protect undocumented immigrants (Intros. 1557 and 1588), ratifying our opposition to President Trump’s anti-immigrant policies. It was a feel-good moment, unless you looked at the fine print. The bills, which were motivated by fear that the NYPD would become the eyes and ears of the Trump deportation machine, had a glaring exception: they didn’t apply to the NYPD. As we speak, there is nothing in New York City law that blocks our police officers from collecting information to help ICE in deporting our undocumented neighbors.

And the pattern goes farther. More recently, my own organization, S.T.O.P., raised concerns about another program that de Blasio supports: OMNY, the proposed successor to the MetroCard. As we document in a just-published report, this new system collects huge amounts of data on every single transit rider, with no meaningful privacy protections.

As with any nearly any personally identifiable information, the more data we collect, the greater the risk. This is especially true for undocumented individuals, survivors of domestic violence trying to hide from their abusers, and countless other New Yorkers with unique security threats. This is why it’s not enough to simply pass Council Member Menchaca’s bill. It’s not enough to simply stop the IDNYC chip, we need to comprehensively review how our city collects, stores, and shares data.

Any time New York City rolls out a new government program we have to go beyond measuring the cost in dollars and cents. We need to understand the privacy price as well.

***

Albert Fox Cahn is the executive director of The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project at the Urban Justice Center, a New York-based civil rights and privacy organization. He writes the monthly "Surveillance and the City" column for Gotham Gazette. On Twitter @FoxCahn.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.