Why I’m Voting No on the CUNY Staff Contract

PSC CUNY rally, with the author center back (photo: @PeteHarrisonNYC)

After over two years of negotiations, the Professional Staff Congress of the City University of New York (PSC-CUNY) and the university have reached a tentative deal on a new contract for the 30,000 faculty, adjuncts, librarians, and professional staff in our union.

The leadership of PSC-CUNY has hailed the contract as a historic deal and part of a larger stand against austerity. In particular, they sight the pay gains for adjuncts, which will increase by 71% by 2022.

As an adjunct lecturer at Baruch College, I would stand to gain from these increases, so even though I was skeptical of the contract campaign (and have participated in #7korstrike actions), I was open-minded and eager to hear my colleagues out. It’s tough to take a position against a pay raise because of my own financial insecurity. I also think the agreement secures legitimate gains. I have no doubt that they weren’t easy to get and that the executive committee worked extremely hard, creatively, and thoroughly.

But as I listened to the (at times heated) debate last Thursday night at the Delegate Assembly, I made up my mind to vote “no” on the contract.

My decision is based less on the technical merits of the contract (here’s analysis for and against) and more about the process that got us here and what it says about union power in New York City today. To me it says that it is time for generational change in union leadership.

People that I respect at the meeting and on other occasions say that our leadership has been fighting austiery and leading strikes against it in education for over 20 years; that this contract campaign is part of a longer-term strategy to defeat it. That tax cuts to billionaires makes it hard to fight.

I agree. Our leadership has been fighting for a very long time under ever tighter budgets and tougher political climates. No contract negotiation is going to result in 100% of our demands. Billionaires are making it really hard to fight back.

But the strategy simply isn’t working. Just in my case, the gains adjuncts will see fall short of our goal of $7,000 per course, which is still short of a livable wage in New York City. The overall increases for everyone won’t keep up with inflation. And it is clear that some of the new money will come from higher tuition and fewer courses for students.

To the union leadership’s credit, they acknowledge the shortfalls and vow to fight on for more in the next contract. I believe them. But it is clear that so many years of fighting against corporate power has diminished the sense of what is possible for many of our leaders. For all the rhetoric of standing against austerity, they have accepted it in practice. What’s more, they’ve done so at a time of immense opportunity for organizing in education.

Just as teachers across the country are striking and winning improvements, the leadership didn’t support a strike authorization (someone even dismissed the success of the Chicago teachers strike compared to this contract campaign). Just as a new level of energy and base-building has emerged among staff and students, the leadership claims that the membership isn’t motivated enough for mass action. Just as the left in America is finding new confidence, allies, and roads to power, PSC leadership has seemingly worked to protect establishment relationships.

I deeply value the years of experience our leadership has in this fight and the knowledge they have about the contract process. There’s no question that they know more than I do about how things work.

But I, and many members and students know that “how things work” isn’t working. The strategy to make change isn’t working. We live it everyday with higher rents, longer commutes, more work, and lower wages.

Just as importantly, I and many others believe that there are better strategies to make things work. We don’t have the time to wait around for incrementalism. We need to elevate new leaders in these spaces to carry on the fight for the future.

Fighting austerity will take mass mobilization of the working class, and not just in education or the public sector. It means building solidarity with gig economy contractors, service industry workers, and tech workers, among others. It means supporting fights for undocumented workers, sex workers, and the victims of mass incarcertaion who sit in jails or can’t find work. All of the pieces are in place and all of the parts are moving. Educators should lead the way.

Voting “no” on this contract and voting instead for a strike authorization should be the spark that unites a general strike against austerity and the billionaire class that thinks they beat another generation of workers. They are wrong.

***

Peter Harrison is a Democratic candidate for U.S. Congress (NY-12) and an adjunct lecturer at Baruch College. He lives in Stuyvesant Town. On Twitter @PeteHarrisonNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Key Piece of the City’s New Trash Overhaul You May Not Be Aware Of

(photo: @BKROT)

For most New Yorkers, the city’s private sanitation industry is mostly out of sight, out of mind. Yet it impacts us in major ways. The industry’s old trucks chug and idle along inefficient routes, spewing pollution throughout the city each night. Once collected, the trash is dumped in communities of color, namely north Brooklyn and the south Bronx. Carters make huge profits while paying their predominantly black and brown workers horrendous wages.

Some workers have reported making as little as $80 for a 16-hour shift. Even more disturbing, some carters have created their own “unions” as a way to block legitimate labor organizing.

In 2013, I started a grassroots, organic waste micro-hauling business called BK ROT. At the time, I thought we were creating a small pilot. Six years later, I have come to realize that we’ve created an entire new sector of zero-emissions waste carters that are highly efficient at diverting large amounts of organic waste from landfills in New York City. When BK ROT started, we were the first micro-hauler in NYC, now there are seven across Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx.

BK ROT offers composting services to homes and businesses not serviced by the city’s sanitation department or by private carters. We collect organics by e-bike and process them locally as a fossil fuel-free alternative. The compost is distributed to local farms for growing food. We hire local youth at fair wages in an effort to combat the high unemployment rates in Bushwick and East New York.

From the start, we strived to be a socially-just operation. Our model was simple: good, green jobs that value workers and keep resources flowing within the community. The service fees covered our operations staff (workers ages 17-24) and leveraged our non-profit status for funding for public educational programing. We went from one worker, who started at 16 and is now 24, to a team of six. In 2013 we processed 300 pounds of food waste a month, in 2018 we did 73 tons, and in 2020 we are on track to capture 250 tons.

When New York City initiated reforms to the commercial hauling industry through the Commercial Waste Zone (CWZ) system, we saw an opportunity to integrate micro-hauling into one of the largest private sanitation systems in the world. As a humble grassroots hauling operation, we knew it would be an uphill battle.

From the jump, it felt overly ambitious to demand that our environmentally-conscious hauling service, powered by teenagers on e-bikes, be included in the city’s massive overhaul. Could we find our stride alongside the likes of multi-million-dollar companies, in an industry historically run by the mob?

We struggled to fit our grassroots solution into policy discussions alongside deeply vested interests. As a new type of hauler, policy-makers were puzzled by our innovative model and not sold on our viability. Mid-way through our advocacy, BK ROT ran out of land to process material because we only had 1,000 square feet of space and a growing list of businesses wanting our services. Our collection rates stagnated as we demanded that the draft CWZ legislation allow us to collect more food waste annually.

Demanding a higher annual collection rate would give us the room to scale up as we worked to overcome barriers such as large capital required for new technology and developing compost distribution networks. Instead of partnering with the bad actors in the carting industry just to grow our collection numbers, we doubled down on our commitment to workers, communities, and the planet.

And, we organized.

We connected with Transform, Don’t Trash, a coalition of environmental justice and labor groups who spent years exposing the private carting industry’s abhorrent practices. BK ROT also gained power by forming alliances with emerging micro-haulers, mostly led by women and people of color. Our new bonds helped forge a stronger voice.

We spent nearly devised a tiered system that defined annual hauling capacities (tonnage) for human powered e-bikes and zero emissions vehicles. We codified micro-hauling within the CWZ framework and successfully secured the ability to haul 2,600 tons of food waste per year.

The CWZ is the most progressive waste management reform in decades. The benefits will be felt citywide, but most acutely in communities of color that have suffered through environmental injustices and labor exploitation.

Our inclusion guarantees further emissions reductions in New York City, while diversifying an industry dominated by white men, as New York City’s micro-haulers are minority- and women-owned business enterprises (MWBEs).

I am incredibly proud of BK ROT, and the win for local micro-haulers. I stand with and remain deeply inspired by the Transform, Don’t Trash coalition that played a leading role in demanding sustainability and accountability in our private waste system.

The existential threat of climate change necessitates taking risks and going big on even the most unassuming ideas. Policy-makers must challenge the boundaries of what is seen as possible. Large scale climate mitigation means recognizing the power of grassroots groups and bringing them directly to the policy table.

***

Sandy Nurse is the Founder and Former Executive Director of BK ROT and a candidate for State Assembly in Brooklyn’s District 54. On Twitter @NurseForNY & @BKROT.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Well-Meaning But Misguided Housing Proposal

Council Member Salamanca (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

A year ago, a homeless woman confronted Mayor de Blasio during his gym workout in Park Slope to ask why the city doesn’t set aside more apartments for homeless people. The incident and a video of it in which the mayor refused to talk with the woman, Nathylin Flowers Adesegun, were widely reported. A few weeks later, City Council Member Rafael Salamanca of the Bronx introduced legislation that would require any rental housing project receiving taxpayer subsidies such as tax abatements, loans, tax credits or reduced-cost land to set aside 15% of its units for people living in the city’s shelters.

The mayor’s comments about the proposed legislation were on target. He said:

“I think that the [current] affordable housing plan works for the people of the city because it is for everyone. It is meant to reach working-class people, middle-class people, low-income people,” and, “I don’t want to send a message that the only folks who can get affordable housing are folks who end up in shelter. I think that’s wrong for everyone.”

Now, almost exactly a year later, Salamanca has re-introduced the same bill but the mayor’s response has been quite different -- he says he is sure he can reach a deal with Council Speaker Corey Johnson.

The mayor was right a year ago and there is no reason to change positions now. His apparent disinterest in or distaste for conflict with the Council cannot be allowed to lead to bad policy that will impede what has been a successful program to build and preserve affordable housing for needy New Yorkers at a variety of income levels.

In 2014 the de Blasio administration issued Housing NY, a ten-year plan to build and preserve a total of 200,000 units of housing in the five boroughs. An important principle of the plan was that the apartments developed would be affordable to families at an array of income levels, from those of extremely low-income, defined as below $25,000 a year for a family of four, to those of middle-income, families of four earning $100,000-138,000 a year, and others in between. The plan projected the distribution of units developed at 20% (40,000) for extremely low- and very low-income households, 58% (116,000) for low-income households, and 22% for moderate- and middle-income households (44,000).

In 2017 Housing NY 2.0 modified the administration’s already-ambitious goals by accelerating its plan, extending it two years, and adding an additional 100,000 units to be preserved or created by 2026. The new targets increased the number of extremely low- and low-income households to be housed to 25% of the total.

Providing affordable housing to New Yorkers at all low- to middle-income levels is important to maintaining a thriving economy and a diverse, vibrant city. As a recent report from the Department of City Planning shows, the city’s supply of jobs far exceeds its supply of housing and we need to generate more places for workers to live.

It is very expensive to build and maintain units for extremely low-income households (approximately $150,000- $200,000 in city capital subsidy per unit for construction, plus ongoing rental assistance) so the rents at higher income levels are necessary to make developments economically viable. The situation is not helped by the fact that the City Council keeps piling on requirements -- like the just-added prevailing wage requirement -- that are not only costly, but deter developers (both for- and non-profit) from wanting to even do deals with the city. It also must be acknowledged that many families in the shelter system need a variety of on-site services in addition to housing, services that private-sector buildings do not provide.

Reasonable people can debate the shortcomings and details of Housing NY, for example, the inclusion of thousands of units in Stuyvesant Town as “preserved” but there is no denying that it has been an ambitious effort that has thus far leveraged over $14 billion in city capital commitments and generated 135,000 units of urgently needed housing.

City officials need the flexibility to design each project based on its overall size, location, and cost; they should not be constrained by arbitrary apartment allocation requirements to particular income levels or types of tenants.

Mayor de Blasio needs no prodding to devote priority and resources to homeless individuals and families. His annual budget provides more than $3 billion a year for shelters, rent assistance, legal assistance, and other homelessness prevention programs, re-housing efforts, and related social services.

So far, about 11% of the units generated by Housing NY have gone to homeless households. Moreover, in 2016 NYCHA started giving preference to homeless families and over the past three years, nearly half of all tenants placed in NYCHA units -- 6,400 -- have been formerly homeless. Another 4,400 homeless families have received Section 8 rental assistance through NYCHA in the same time period.

The City Council should not create a one-size-fits-all set-aside that would tie the hands of the Mayor, Deputy Mayor for Housing, and other city officials who are trying to spur as much housing construction as possible and who are already motivated to create units for homeless families without compulsion.

If the 15% homeless requirement is in addition to the 25% proportion of units Housing NY 2.0 already requires for extremely low-income units, it will make some projects so costly that they will not be built. If the homeless allocation is instead made part of the total number of project units allocated to low-income families, it will take much-needed units out of the pool available to the thousands of other families earning less than $25,000 a year who also need decent and affordable places to live in New York City. Neither is acceptable.

The Council’s focus should be on streamlining the process for project approval and creating more new affordable housing across the income spectrum, not counterproductive requirements and virtue posturing.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

From the 'Third Party' Front Lines, How to Address Fusion Voting, Party Qualifications, and New York Democracy

Howie Hawkins, the author (photo: Green Party)

“The Democrats’ Secret Plan to Kill Third Parties in New York,” as reported by The New York Times (Oct. 29), brings to mind how the Democratic Party establishment manipulated the 2016 primary process to favor the corporate candidate, Hillary Clinton, over her progressive challenger, Bernie Sanders.

Now the New York Democratic Party establishment, led by the Governor Andrew Cuomo-appointed chair of that party, Jay Jacobs, proposes to silence bothersome third parties by increasing by five times (from 50,000 to 250,000) the number of votes needed by a party’s gubernatorial ticket to qualify the party for the ballot.

It is no secret that Cuomo, Jacobs, and other establishment Democrats are irritated by public criticisms and primary challenges from the Working Families Party, which functions as a progressive faction of the Democratic Party. The WFP uses its ballot line as political leverage in the Democratic Party by threatening and sometimes mounting primary challenges to establishment Democrats, although it almost always runs the Democratic primary winner on its ballot line in the general election.

A much bigger issue is at stake here than this internal Democratic squabble: the people’s right to have the full diversity of their voices and choices participating in elections. Election law reforms should promote multi-party democracy, not cement in place the two-party system of corporate rule where both major parties are financed by wealthy special interests.

As the Green Party candidate for governor three times between between 2010 and 2018, I came in third each time among five to seven candidates. I received between 60,000 and 184,000 votes, the latter total accounting for 4.8 percent of the total vote. Our vote was always above the longstanding 50,000 vote standard but well below the 250,000 votes that Jacobs proposes. Jacobs is targeting the Green Party’s very right to participate in elections.

Jacobs justifies his proposal by saying New York needs to eliminate the corruption of “sham” parties that trade their ballot line for political favors. The Green Party is by no definition a “sham” party. The Green Party runs its own candidates against both establishment parties. It doesn’t accept donations from corporate interests. It doesn’t trade its ballot nominations for favors from the major parties. It is not a faction of the Democratic Party, like the WFP, nor a faction of the Republican Party, like the Conservative Party. It is not for sale to the highest bidder between the two major parties, like the misnamed Independence Party.

Jacobs also said he wants to reduce voter confusion. Here I agree. In the 2018 election I faced four Cuomos and three Molinaros on the ballot in this order:

| Democratic | Andrew Cuomo |

| Republican | Marc Molinaro |

| Conservative | Marc Molinaro |

| Green | Howie Hawkins |

| Working Families | Andrew Cuomo |

| Independence | Andrew Cuomo |

| Women’s Equality | Andrew Cuomo |

| Reform | Marc Molinaro |

| SAM | Stephanie Miner |

| Libertarian | Larry Sharpe |

The ballot should have had five ballot lines for the five candidates instead of ten ballot lines for each party making a nomination. New York’s “disaggregated fusion,” where every party nomination creates another ballot line, does indeed make for confusing ballots.

Future ballots should be simplified by putting all the party nominations a candidate receives under their name instead of giving them a separate ballot line for each party nomination. Most states that permit multiple party nominations use this “aggregated fusion” of one ballot line per candidate, including Delaware, Idaho, Mississippi, Oregon, and Vermont. Aggregated fusion was used by New York City on its ballots when it had ranked-choice voting for proportional representation on the City Council from 1936 to 1947.

Aggregated fusion ballots for New York would require a different standard for ballot qualification than the current 50,000 votes for the party’s gubernatorial ticket. New York is unique among the states in having a fixed number of votes for governor on a party’s separate ballot line as the sole standard for ballot qualification. Most other states use the more reasonable standards of a minimum party enrollment and/or a minimum percentage of the vote. In New York, we should allow parties to qualify for the ballot by either having a minimum number of party enrollees – 20,000 would be reasonable – or by receiving 1 percent of the vote for any statewide office.

It would also serve fair elections to have the candidates listed in random order, with a separate page for each office and random ordering of candidates on each page. Political scientists have found a ballot name-order effect of 1 percent to 10 percent, with the effect increasing on down-ballot, low-information contests. We don’t have to cram every office and ballot proposition onto one page. We don’t use lever machines to record votes anymore.

Ballot access in the United States is more difficult than almost every other electoral democracy in the world. To qualify independent candidates for the ballot for national legislatures, it takes two signatures in New Zealand, 10 signatures in the UK and India, 50 signatures in Australia, 100 signatures in Canada, and 200 signatures in Germany. In New York, it takes 3,500 signatures for independents to get on the ballot for Congress. Many states’ signature requirements for independent congressional candidates are more restrictive. Illinois, for example, requires 5 percent of the district total vote in the previous election, which comes to over 15,000 signatures.

Party suppression in America is part of the broader problem of voter suppression. Many voters stay home because they believe that the Democrats and the Republicans do not represent their concerns. Instead of restricting the voices and choices in our elections, we should expand them by instituting proportional representation in legislative bodies, as do most electoral democracies around the world.

Under proportional representation, each party gets representatives in the legislative party in proportion to the votes its candidates receive. No vote is wasted. Every vote counts toward getting your party its fair share of representation. When New York City had proportional representation, the number of parties represented in the City Council increased from two to between five and seven for each two-year cycle.

Third parties are attacked by major party partisans for “splitting the vote” in our single-member-district, winner-take-all system. Many voters feel compelled to vote for a “lesser evil” major party candidate instead of the third party candidate they really prefer in hopes of preventing a victory by the other major party candidate they fear more. Proportional representation ends the vote-splitting problem for legislative races.

For single-seat executive offices, the answer to vote-splitting is ranked-choice voting. Voters rank their choices in order of preference. If no candidate receives a majority in the first count, the last place candidate is eliminated and their voters’ ballots are transferred to their second choices. That process continues until a candidate receives a majority of votes. Ireland, Malta, and Sri Lanka elect their presidents by ranked-choice voting. Maine will award its electoral votes in 2020 by ranked-choice voting. New York City voters just approved ranked-choice voting, but it will only apply to city-level offices and only in party primaries or special elections, not general elections.

Many prominent Democrats blame Green Party candidates like Ralph Nader in 2000 and Jill Stein in 2016 for their own losses to Republican presidential candidates, as Hillary Clinton did again last month. The last two Republican presidents, George W. Bush and Donald Trump, were first elected despite losing the popular vote. The Green Party didn’t do that. The Electoral College did. Instead of picking on the Greens, the Democrats should join the Greens in fighting to end this problem by replacing the archaic anti-democratic Electoral College with a national popular vote for president using ranked-choice voting.

The Democrats’ plan to eliminate third parties in New York is a plan to reduce democracy. Let’s support reforms that expand democracy, including fair ballot access, fair ballots, proportional representation, ranked-choice voting, and public campaign financing

***

Howie Hawkins, a three-time New York gubernatorial nominee of the Green Party, is currently a candidate for the Green nomination for president. On Twitter @HowieHawkins.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Small Business Plea to the City Council and Public Advocate

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

As the owner of a small retail shop it is stomach-churning to publicly state that I do not support a piece of city legislation that would mandate 10 days of annual paid leave for all working New Yorkers at businesses of five or more employees and comes in addition to the mandated five paid sick days assured under the 2014 Paid Safe & Sick Leave law.

I believe paid time off is a just right and I am a fierce defender of my staff. Contrary to the words used by Mayor Bill de Blasio in stumping for this bill, I do not see my employees as mere “cogs in the machine.” But while rents, real estate taxes, and regulatory compliance costs remain so high, small businesses simply can’t afford increased payroll.

We must call on the City Council and the Public Advocate to help lift up what is actually working in our communities instead of mandating higher costs to doing business. The plea is simple:

First, understand the economic impact of 15 paid days off on the operational costs of small retailers, restaurants, bars, grocery shops, hair salons, and other service providers that cannot delay or pass off projects when an employee is out.

In my retail shop of 10 mostly full-time staff, paid leave time ranges between five and 13 days, including the mandated five paid sick days (which staff use for sick or vacation time). If the paid vacation time bill (Int. No. 800-A) is to pass, my annual payroll costs would increase 2.9 to 4.1%. If you don’t know that this is a meaningful increase, you do not run a small business.

Unlike an office, retailers only make money when we are open and staffed. When an employee takes paid time we fill the shift with another employee. This means paying two people for the same shift and often paying one shift at overtime rates. I have accepted that as part of the cost of doing business, but the payroll jump that this bill contemplates may eliminate our annual bonus pool and/or cause wage stagnation.

We simply cannot pass on these costs to our customers because it is their limited ability to afford the goods, meals, or services sold that matters most to our success.

Second, understand the data being used to decide this critical legislation and who is actually at risk.

When businesses raise concerns about this bill, the mayor and Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, who has been its lead sponsor since he was a City Council member, typically pivot to two data points. First, they claim that the impact on business is overblown. They cite a study conducted by the Center for Economic Policy & Research at CUNY on the impact of paid sick leave, which concluded that the law has been “no big deal” for the 382 businesses interviewed. Only a minority of respondents in this study fit the category of small retailer, restaurant, bar, or grocer, however. This is borne out by the study’s finding that 84% of respondents relied heavily on two means by which to handle paid sick days: put the work on hold or temporarily assign work to other employees; two options that retailers and hospitality businesses simply don’t have.

In 2019 the NYC Hospitality Alliance did its own study, interviewing several times more hospitality and retail businesses about the impact of paid sick leave. It showed 49.6% of these businesses said that paid sick leave has cost their business significant additional money, and 81.1% claimed that they pay another employee when one takes a paid day off. Perhaps most tellingly for the future of small business growth, 58.7% stated that these costs have prevented them from reinvesting in their business.

The second key point is real stories from working New Yorkers who talk of being fearful to ask for just one paid day off. These are sad stories but they involve employers who are not even abiding by the paid sick leave law. Let’s not lose sight of what most small businesses do to support the well-being of their staff.

Third, recognize that this bill would weaken the competitive edge of small retailers in the most expensive city in the country.

I am not aware of any city in the world that mandates paid vacation time without it being a federal mandate. To face increased payroll costs at a time of disruption from online retailers is untenable.

Recent reports from the Department of City Planning and Comptroller Scott Stringer demonstrate a rise in vacancy rates and cite retail rents, property taxes, and regulatory burdens as significant drivers of this reality. The Comptroller links vacant storefronts to lost job opportunities and income for New Yorkers. At the same time, a recent New Yorker article depicts poor working conditions for employees of Amazon and a recent New York Times article highlights incredible congestion and pollution resulting from the city’s growing reliance on quick deliveries.

What do we want our city to be? There have got to be better models than that of Amazon and the answer is to help incubate local ones.

Fourth, fund paid leave by means other than a mandate on small employers.

It is imperative that we look at other means by which to fund paid leave. First, consider that total income (profits) is a better determinant than employee number for gauging which businesses can afford mandated leave. Second, look at established models like New York state’s paid family leave law. All New York City employees could contribute a tiny percentage of each paycheck to fund a paid vacation benefit.

Using total income as a determinant, small businesses could receive an annual reimbursement calculated at some percentage of total payroll costs incurred. Yes, this would take time and no, this would not be simple. But this is exactly what we expect of our elected officials - to never be afraid to do what is hard.

***

Natasha Amott is the owner of Whisk, in downtown Brooklyn. On Twitter @Natasha_Amott. She can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ten Examples of How Our Business Improvement District is Thriving

Spring Street Park (photo: Hudson Square BID)

International marketing, advertising and public relations firms; a medical tech company; an incubator for artists and performers; a genomic research institution; a local pharmacy, the home of three of the nation’s leading public radio stations; a billion-dollar travel website.

While they serve different audiences and tackle different challenges, they share a certain spirit of ingenuity that tends to define great businesses and innovative thinkers.

They also share a neighborhood: the public parks, the local haunts, the happy hour spots, and the crosswalks of Hudson Square. The spaces where creative minds meet to debate the biggest questions facing their industries and their clients.

Hudson Square has always had some of that spirit. It’s an area where George Washington set up his headquarters in 1776, where free black men gathered to publish a newspaper in 1827, and where most of New York City’s top print shops flocked in the 1920s as they pushed at the creating edge of communication.

Sure, plenty’s changed since then – but when you look at what’s going on today in Hudson Square, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the spirit never left.

I know the feeling firsthand. Our team was proud – and slightly nervous – to help launch the Hudson Square Business Improvement District a decade ago, some time after the neighborhood had entered its latest chapter and begun drawing in great minds of the digital age.

By beautifying public spaces, creating more amenities for local workers, and building a real culture for the neighborhood, the BID has helped transform what was once known as Manhattan’s Printing District into a thriving creative hub. Hudson Square has now attracted approximately 1,000 diverse businesses that employ over 60,000 people. We’ve seen more of the world’s largest companies make moves into our slice of the city (Google and Disney among them), just as we’ve seen older champions of the area drive their foundations even deeper.

It fills us with pride, even as every step reminds us of just how much work it can take to keep these blocks teeming with the energy they demand.

Working collaboratively, the BID has helped arrange public-private partnerships and forward-thinking investments, positively transforming our streets and green spaces. Today’s workers of Hudson Square grab lunch in Spring Street Park with outdoor Wi-Fi that keeps them tuned into their daily inspiration; are greeted off the subway with world-class public art; and have access to unique after work programming that truly engages them to participate and share in the growth of the neighborhood.

This past year, as one of our gifts to the neighborhood, the BID commissioned Hudson Square Canvas, a public art initiative that features large-scale, original street art that range from sweeping, hand-painted murals to a dramatic, 90-foot-long multicolored sculpture.

So as we take a breath to celebrate the BID’s 10th anniversary, it only made sense to recognize and honor 10 Hudson Square businesses that continue to embody that dynamic spirit and ensure that the creating edge is here to stay.

We call it, simply enough, our 10 in 10 – and although it names a fraction of the incredible companies that call Hudson Square home, we think it’s enough to provide everyone a taste of what we’re all about.

After all, while the loft spaces and the light never hurt, it’s the compelling human and entrepreneurial stories of our neighborhood that define it. When we take some time to hear those stories from just a few of the women and men who’ve been part of Hudson Square’s growth, we can all learn something about what makes real community-building so special – and so crucial.

Of course, it follows that every thought of a 10 in 10 inspires new dreams of what the 20 in 20 – and beyond – could look like. And on those days, it’s good to be in a place where such visions tend to be realized in stunning ways that perhaps no one had thought possible.

***

Ellen Baer is President and CEO of the Hudson Square BID. The full list of the BID’s 10 in 10 honorees can be seen here. On Twitter @HudsonSquareNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Faulty Notion to Restrict Political Party Qualifications in New York

(photo: Philip Kamrass/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

In April, the New York State budget was passed and signed into law. Buried within it was the creation of a commission tasked to write a new law on three aspects of the state’s election code: public campaign finance, “fusion” voting, and political party qualifications. Oddly, though it’s called the Public Campaign Finance Commission, most of the hearing testimony and press coverage has focused on fusion voting and party qualifications. This may be so because the commission’s informal leader, Democratic State Chair Jay Jacobs, has not disguised his desire to eliminate the minor or “third” parties in the state.

Jacobs has suggested raising the “threshold” number of votes required by a political party to achieve and maintain automatic ballot status. This is what “party qualifications” means. It answers an important question that all states must face: How does a group of citizens who form a political party get that party listed on the ballot?

Right now in New York, a party must receive 50,000 votes in each gubernatorial election under its own banner, or on its “ballot line,” as New Yorkers call it. Right now, based on the 2018 election, there are six qualified minor parties in the state: the two most prominent are the Conservative Party and the Working Families Party.

The 50,000 vote threshold is approximately 1% of the gubernatorial vote. Jacobs has proposed quintupling the vote requirement to 250,000, or roughly 5%, and extending to both gubernatorial and presidential races.

Because New York, unlike most states, does not permit minor parties to qualify in any other manner (such as a petition), this would effectively put the minor parties out of existence. It would instantly make New York among the most restrictive states in the nation in terms of ballot access for citizens who are neither Democrat nor Republican. And it is in stark contrast to the trend in other populous states. In the last 20 years, five of the most populous states — California, Texas, Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania -- have moved in precisely the opposite direction, reducing barriers to minor party qualification, not raising them.

More states use a 1% threshold than any other percentage test. The second most popular requirement is 2%. If New York adopted either of those, it would at least be within the realm of the defensible. But any standard greater than 2% not only smells bad, it will likely be ruled unconstitutional in the federal courts. There are dozens of cases holding that overly onerous party qualification rules are unconstitutional. Surely the lawyers on the commission understand that if “equal protection” means anything, it is that “party qualification” rules designed to punish or eliminate minor parties (and the voters who support them) will not stand.

The New York Commission, binding recommendations from which are due by December 1, should also consider the legal problem presented by a 250,000 vote threshold. It will likely be ruled unconstitutional in the federal courts. There are dozens of cases holding that overly onerous party qualification rules are unconstitutional. Surely the lawyers on the commission understand that if “equal protection” means anything, it is that “party qualification” rules designed to punish or eliminate minor parties (and the voters who support them) will not stand.

If the State Legislature wishes to ban fusion voting, it should do so in the proper way: pass a constitutional amendment, and refer it to the voters for approval. In the meantime, this unelected commission should leave the minor parties alone, and not touch the 50,000 vote threshold. The Legislature can consider it in the regular order of business.

The minor parties may annoy the major parties, but democracy is not about limiting ballot access only to those with whom you agree. The commission should resist joining the company of Alabama, Virginia, or the other states that have essentially made it impossible for “third parties” to qualify. Democracy belongs to everyone, not merely the two major parties.

***

Richard Winger publishes the Ballot Access News newsletter and website. On Twitter @ballot_access.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Local City Council Members Must Head Back to Drawing Board on East River Park Plan

(photo: @ERPAction)

An Open Letter

Dear City Council Members Carlina Rivera, Margaret Chin, and Keith Powers:

You have indicated that on Thursday you will vote for the flood control plan that will demolish East River Park and rebuild it 8-10 feet higher over five years. This is a $1.45 billion, five-year project that will destroy more than a mile of coastline park that is vital to our neighborhood, the un-wealthy end of the Lower East Side and East Village. I urge you to change your vote to “no” on Nov. 14. Here’s why:

Once this plan passes the City Council, you will lose all bargaining power. The city will not be obliged to reply to the many unanswered questions or do any of the things it has promised to look into, such as these points:

Interim Flood Protection

The city promises to study temporary flood protection while constructing permanent solutions. If you vote to accept this East Side Coastal Resiliency plan, the city will not be obliged to offer a single sandbag through years of hurricane seasons (the city says three years—but we’ll talk about timelines later).

Phased Construction

During phased construction (keeping sections of the park open during construction), the entire mile-plus promenade along the river will be closed for at least two years. That is so that the eight-foot flood wall can be built. If pile driving is going on the entire length of the park, the promised 42 percent of the areas still open will be unbearably noisy. In addition, there will be no access to the river at any point along the water for those years (and likely much longer—again, see timelines). As the barrier rises, we will be imprisoned behind a metal wall. Do you find that current phasing scenario acceptable? Your neighborhoods will be horrified when they figure it out.

That is leaving aside whether it’s acceptable at all because phased construction will still destroy the whole park—just over a longer period of time than closing the whole park at once would have. We are proposing an environmentally and socially conscious alternative.

Health Risks

The dust from digging up contaminated soil and adding layer after layer of landfill will clog our lungs. Our Lower East Side/East Village neighborhood already suffers high rates of asthma and 9/11-related respiratory troubles. The 1,000 trees that help us breathe will be gone. We need picnic areas, ball fields, greenery, and river access for our mental and physical health.

Alternate Park Spaces—Mitigation

Have you gotten the greenway you have been requesting to substitute for the loss of the biking/running/strolling path along the river? No, you’ve gotten a promise to study the possibility of a protected bike lane. Have you gotten the free ferries from Corlears Hook to Governors Island you’ve been requesting? No, that’s not even mentioned in the agreement you reached with the city as announced on Tuesday. Are you satisfied with a few playgrounds repainted or covered with artificial turf? Are you satisfied with the progress of greening of the streets and creating of play spaces and BBQ areas to substitute for the loss of mature trees and all the heavily used picnic, lounging, and natural areas we have now in East River Park? You should know that the thousands of saplings promised for our streets and the new park will not come close to the size of the 1,000 lost trees.

Timelines

Do you trust the five-year timeline the city has provided? The city has no answers to how long it takes for the eight feet of fill to settle. They do not know how long digging up and wrapping ConEd lines will take or how to deal with the contaminated soil that will be dug up. This is acceptable to you?

Even if the city could tell us how long the above complications will take, you know the city is not good with deadlines. Surely you see that in the tiny Luther Gulick Park on the Lower East Side a bathroom has been under construction for four years. You know it took 10 years to rebuild the promenade in East River Park. Do you think voters will mind not seeing the river for another 10 years?

Construction

The city says the park will stay completely open until fall 2020. In the summer work will be done in the park, however. What work? Where? How noisy and dirty will it be?

Community Advisory Board

What authority will the newly announced community advisory board have about any of the issues raised above? What authority will you as the local elected officials have?

Your constituents have been working hard to convince you to vote “no” on the ESCR. At a Nov. 4 rally on the steps of City Hall, representatives of grassroots community groups delivered more than 8,000 petition signatures to the mayor. Two thousand of those signatures came from NYCHA residents, who eagerly signed. The team who gathered those names did so to show that NYCHA residents do not support the plan, despite what NYCHA Tenant Association leaders say.

We announced a letter signed by 50 community and conservation groups from around the city. We’ve been testifying and demonstrating our hearts out for a year. You say you listen and respond to the community, but you have not heeded our thousands of voices.

We insist on a plan that will provide flood control with minimal destruction of existing parkland and biodiversity.

We want interim flood protection.

We don’t want to contribute to climate change in order to cope with climate change.

We want our low- and middle-income neighborhood to be treated with the respect that wealthy neighborhoods receive. You know this kind of destructive, ugly plan would not be acceptable in a rich neighborhood. Witness how fast the city dropped the plans to put a six-lane highway where the Brooklyn Promenade is.

We do not want East River Park destroyed. You can do better. Our neighborhood deserves better. Vote no!

Sincerely,

Pat Arnow for East River Park ACTION. On Twitter @ERPAction.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Surveillance and the City: Past Time for the POST Act

(photo: William Alatriste & John McCarten/City Council)

What’s a majority of 51? It should be simple math, but in the world of City Council politics, the numbers don’t always add up. Take the Public Oversight of Surveillance (POST) Act, an NYPD reform bill that has been pending before the Council for over two-and-a-half years.

Twenty-nine of the 51 Council members and the Public Advocate support it. No, they don’t just support it, they’ve gone further and fully co-sponsored the long overdue NYPD spying reforms. But the bill still isn’t law.

That’s because none of those 29 members have voted for the POST Act -- they haven’t been given the chance. Despite the clear majority support and long delay, we’re still waiting on Speaker Corey Johnson and Public Safety Committee Chair Donovan Richards to hold a hearing on the bill. If we can’t get a hearing, we can’t get a vote. And if we can’t get a vote, it doesn’t matter how many New Yorkers and Council members are crying out for reform.

The POST Act is modest, but vital. At a time when the NYPD is buying invasive and discriminatory tools to track and spy on communities of color, the POST Act simply demands transparency. Tell the public what you bought and what the privacy safeguards are, and undergo an annual audit. That’s it, that’s all this simple bill requires, and, mind-bogglingly, it’s still not law.

The truth is that out of a Council of 51 members, there are only two that matter in getting you to a vote: the committee chair and the speaker. There isn’t a mysterious force that magically chooses which bills move forward, though of course there is vocal opposition from the NYPD and police unions. There isn’t some anonymous assembly of bureaucrats that decides: it’s two people. Which is why after years of campaigning for passage of the POST Act we’re turning to Speaker Johnson and Chair Richards. We’re speaking to them directly and demanding a hearing and full Council vote before the end of the year.

Maybe the police unions will be upset. Maybe Fox News will push back. The maybes are endless. This is what we do know for sure: it is time to act. As New York City drags its feet on digital civil rights, cities across the country are stepping up to go further. Cities have passed versions of the POST Act that are far more aggressive than what we demand. Do they demand information? Yes. Do they have audits? Yes, but then they also require lawmakers to approve each and every spy tool their police forces buy. Some cities like San Francisco have gone farther still and started banning popular forms of surveillance like facial recognition.

San Francisco lawmakers acted because of the risk that this Orwellian technology might be used on their streets, but facial recognition has already been used to digitally profile tens of thousands of New Yorkers, and our own lawmakers have done almost nothing. How is it that our neighbors are being arrested and convicted on the basis of this racist and unproven technology, 998 just last year, and our response is to do nothing?

Recently, Speaker Johnson was asked if he would commit to passing the POST in 2019. Even though he co-sponsored the bill in 2017 and said he supports the “aims and the goals of POST Act,” he refused to give a timeframe. This is why a coalition of 70 civil rights and community-based organizations recently spoke up, sending a letter to Speaker Johnson. We made it clear that delay is not an option and that evasion will not be tolerated. No, we will keep fighting and we will keep pushing until we get our long-delayed hearing and vote.

Let’s be clear, the POST Act isn’t the end of the fight for surveillance reform, but it’s an indispensable first step. For years, the NYPD has thwarted the tools used to hold police accountable for discriminatory surveillance. They fight discovery, freedom of information law requests, and every other mechanism that could provide us insights on our communities are being surveilled.

In a low point last year, the de Blasio administration fought in the state’s highest court to create a new legal doctrine. Taking a page out of the CIA’s Cold War playbook, the NYPD now will no longer confirm nor deny if they have records about certain types of surveillance. This means that even where these tools are used to racially and religiously profile New Yorkers, we simply can’t get the data to show it.

With every other form of governmental transparency cut off, we need the POST Act. We need it to understand what systems are on our streets, but also how the data is being used. We need to know what safeguards are in place for innocent bystanders, and how we prevent information from being shared with federal agencies like ICE. In short, we need rules of the road, and we need them now.

***

Albert Fox Cahn is the executive director of The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project at the Urban Justice Center, a New York-based civil rights and privacy organization. He writes the monthly "Surveillance and the City" column for Gotham Gazette. On Twitter @FoxCahn.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

MTA May Have Halted Subway Ridership Decline, But Gains Very Fragile

(photo: Marc A. Hermann/MTA New York City Transit)

The New York City Transit and Bus Committee of the MTA Board reported at its October 2019 meeting that weekday ridership of the subway grew 1.4% in September of this year compared to last, and that there have been four straight months of subway ridership gains. The MTA put out a gushing October press release that subway weekday ridership this September was up 4.5% over September 2018, and bus weekday ridership was up 1.5% over September 2018.* Revenue was up over forecasts as well.

The MTA attributed the improvement to the Subway Action Plan and a restoration of on-time performance to 82.7% in September 2019, compared to 69% a year prior. The Subway Action Plan invested heavily in operations and maintenance improvements like eliminating track fires, deploying emergency personnel, fixing signals and track, more rapid repairs, as well as other measures like increasing speeds on subway lines where speed limits had been imposed starting in the 1990s.

This is obviously good news since subway ridership peaked in 2015, stayed flat in 2016, and declined in 2017 and 2018. State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s office has estimated that the ridership decline is costing the MTA $250 million a year. Any revenue gains are welcome, especially to the extent that they reflect improved public confidence in the mass transit system.

Despite the recent improvement, MTA documents still acknowledged that average weekday ridership for all of New York City Transit (subways and buses) was still down 0.6% from the prior year-over-year (September 2017-September 2018, verus. September 2018-September 2019), so a recovery is actually just beginning.

But the subway ridership gain is especially fragile because the MTA is projecting deficits of $1.9 billion by 2023 before fare and toll hikes and its budget reduction and “transformation” plans are implemented, after which there is still a projected deficit in 2023 of $433 million.

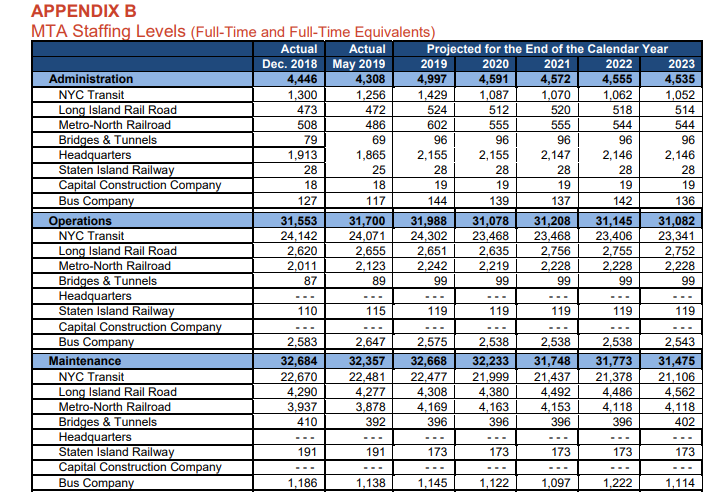

Unfortunately these plans to address deficits include staff reductions of 3,000-4,000 jobs, including reductions of 2,300 jobs in operations and maintenance personnel at New York City Transit from the 2019 staffing peak related to the Subway Action Plan.

Below is a table taken from the Comptroller’s report using the MTA’s projections.

It is uncertain how the MTA will preserve the on-time performance and ridership gains while cutting 2,300 operations and maintenance personnel.

Projecting the revenue gains from the September ridership increases would yield another $100 million for the MTA in 2020, perhaps higher by 2023. This is just back-of-the-envelope math, but the potential of retaining, regaining, or gaining more riders is there and that’s why personnel cuts of such magnitude are problematic.

The MTA is also hiring 500 more police officers, at an estimated cost of $50 million a year, for various public safety and fare evasion deterrence purposes, without booking any more revenue from the fare evasion deterrence. The agency says fare evasion now costs it $260 million a year. The MTA has yet to provide any metrics or a clear plan for how the extra cops will be worth the cost, but I would still give the extra cops the benefit of the doubt at a minimum at deterring crime. The MTA owes the public a better explanation for what benefits the new officers will offer.

Even a revenue gain of $100-$200 million a year from improved ridership won’t be a miracle for the MTA when it faces deficits of $1.9 billion a year, with $433 million still left after implementing current plans by 2023.

When the Legislature provided funding for the Subway Action Plan and the new congestion pricing and various tax hikes for the 2020-2024 MTA Capital Plan, it left the MTA little extra room to address its deficits. The Action Plan funded staff-ups for service improvement, most of which need to be sustained (and the money spent). Congestion pricing and the other new revenue is prohibited from being used for operating deficits. Essentially Governor Cuomo and the Legislature left the MTA stranded and needing to find a way internally to cope with its deficits, which involve a mismatch between revenue, including its farebox and dedicated taxes, growing at 1% a year, and its costs, growing at 3% a year, mostly debt service costs and health insurance.

With the Legislature up for election next year, tax increases are unlikely. But there are still large sums of money unspent in the Dedicated Infrastructure Reserves set up from the Financial Settlements over the past years. Just giving the MTA $150 million from the reserves next year to preserve operations and maintenance services (and the ridership gains), to New York City Transit and commuter rail, would give the MTA more time to continue the gains of the past year and find efficiencies without harming service.

In 2021, the Legislature could look at some modest new sources of revenue, like the for-hire-vehicle surcharges, or substituting some sources of revenue for the MTA with others that more closely correlate with economic growth.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

*The MTA notes its ridership numbers may be subject to future revision.

City Council Must Act Now to Protect the Lower East Side

(rendering: City of New York)

It has been seven years since Superstorm Sandy made landfall on our city, causing billions of dollars in damage and ravaging some of our city’s most critical infrastructure, including our parks. It took years for the famous boardwalks in Coney Island and the Rockaways to re-open. Trees across our coastlines died and continue to be at risk from exposure to salt water. And many of our coastal parks are no less protected from the next big storm today than they were in 2012.

As a steward and advocate for our city’s parks, I know that we can’t pass up an opportunity to protect our coast and our parks in Lower Manhattan with the East Side Coastal Resiliency project (ESCR). This project, built the right way, can protect East River Park and the neighborhoods surrounding it for generations.

When the city initially proposed a revised ESCR design, my organization, New Yorkers for Parks, voiced our frustration. East River Park is one of the few large, open green spaces with baseball and soccer fields in Lower Manhattan, and so many low- and middle-income New Yorkers rely on it as a home away from home. We made it clear that we would only support a plan that used phased construction, preventing the long-term displacement of park-users from the area.

Today, thanks to the advocacy of City Council Members Carlina Rivera, Keith Powers, and Margaret Chin, as well as Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, the city has committed to a construction plan that is phased, ensuring nearly 50 percent of the park remains open at all times. In addition, the city has provided a plan to ensure local youth sports teams can continue to play in the park and at surrounding sports fields and parks, many of which are receiving long-overdue repairs and upgrades.

And a new tree planting campaign has already been launched in the neighborhood, with over 1,000 trees expected to be planted in addition to the hundreds of new trees replacing the dead or aging trees in East River Park.

But in order to make this plan truly work for the most impacted communities, we must continue to call on city agencies for greater involvement and community coordination. Part of that effort must include new major maintenance investments in this park and others so that our parks do not fall into disrepair. It is not enough to simply rebuild a park: it is our duty to maintain it, especially when it is our first line of defense for climate change.

It’s expected that ESCR will provide coastal protections within three years. But if the City Council fails to approve this land action now, the project would likely never return, and we will lose the $335 million in federal funds that must be spent by 2022. This funding is a one-time opportunity. Losing it would be yet another tragedy.

Lower Manhattan residents deserve a park that will not only protect their homes but will protect their future. The city has never embarked upon a resiliency plan of this scale - and while the project may not be perfect, we have to start somewhere.

During Superstorm Sandy, water infiltrated all five boroughs; storm surges don’t discriminate. Other stretches of our waterfront will require similar investments in the not-too-distant future.

The time to plan is now. The time to act is now. Let’s make this happen.

***

Lynn Kelly is Executive Director of New Yorkers for Parks. On Twitter @lynnbod & @NY4P.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.