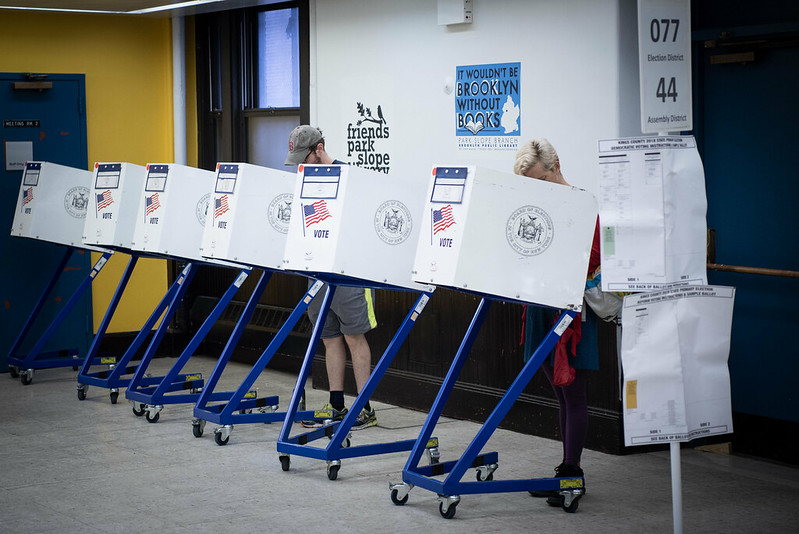

Major questions about voting during coronavirus hang in the balance (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

As the American people hunker down under a patchwork of evolving emergency orders and health directives, our communities are grappling with extraordinary circumstances disrupting and reorienting our lives and the economy. To flatten the curve of community spread during the increasingly deadly COVID-19 pandemic, Governor Cuomo has placed New York on PAUSE; Health officials have issued stay-at-home and social distancing directives; schools, playgrounds, and non-essential facilities are closed. Further restrictions may be imposed. The duration uncertain.

But when it comes to the fate of civil rights during states of emergency, historically the paradigm is less uncertain—there is an irresistible tendency across the globe for authorities to suspend the normal order in the name of imminent, amorphous threats of unknown duration, leading to the incremental curtailment of freedoms that we take for granted (like unfettered travel, transportation, assembly, and enterprise to name a few). The new normal makes prioritization of due process seem quaint, but it is even more critical when the exigencies of the moment impose security measures that inadvertently raise old voter-access hurdles to new, perhaps insurmountable heights.

In this case we can dispense with skepticism over the emergency itself. The pandemic is most certainly real. But already, COVID-19 has scrambled our democratic process. The Democratic National Committee has postponed its convention as 15 states are postponing 2020 primaries and some are adjusting voting policies so residents aren’t forced to choose between safety and casting a ballot. That’s the goal.

Now that Governor Cuomo has postponed New York’s April presidential primary and several special elections until June, and gone even further to implement universal absentee ballot access by executive order due to the coronavirus concerns, there is a timely opportunity to rebalance and calibrate reasonable access to civil rights for the moment we are in—a perpetual state of emergency during pivotal 2020 elections. To do so, policymakers in Albany and administrators at the State Board of Elections and our 58 county boards are grappling with at least three significant voter access questions.

First, what changes will need to be made to the traditional election day footprint, from polling place siting and layouts to staffing, to comply with public health directives that will continue to evolve? Second, is there a feasible, fair, and secure way to expand and scale New York’s traditionally limited vote-by-mail program as an alternative to voting in person? And third, what role should New York’s new nine-day early voting period play in calibrating this balance between public safety and voter access?

As counties prepare for consolidated June primaries and the 2020 general election, they do so amid much uncertainty about the trajectory and time-horizon of the COVID-19 pandemic. Will this all be a distant memory by late June? Will the pandemic be with us in November, depressing turnout and spreading even further, as occurred in the 1918 midterms?

Without the benefit of hindsight, policy-makers must plan for a circumstance where it may be impossible to staff or unwise to deploy the traditional sprawling election day footprint, with voters assigned to one of thousands of polling places across the state, many of which are sited in facilities deemed too dangerous or vulnerable to be open to the public today, and based on siting schematics and occupancy assumptions unworkable under the public health directives currently in place.

While we are eager to embrace modern, tech-based approaches to our antiquated voting laws that would obviate much of this conversation, mobile voting is in its infancy and comes with documented and unresolved security pitfalls while perpetuating the digital divide in our communities. Moreover, without any infrastructure in place, it could be folly to roll out an entirely new and untested system now. So what tools are actually available during the present emergency?

To prepare, the State Board of Elections should develop and issue a continuity guidance, to be implemented as needed, that outlines and directs the tools counties should use to maintain access, protect public health, and responsibly reduce the election day footprint.

First and foremost, local administrators must embrace early voting and the vote-by-mail alternatives available as the principle means for shifting turnout density away from Election Day.

However, New York has a longstanding culture of Election Day voting and is not equipped to entirely jettison that model now. Given that reality, county boards will need to reassess siting plans and have the flexibility to consolidate and reallocate election districts, polling places, and resources, with timely notice of the changes provided to impacted voters. In some cases, alternative sites will be needed so counties can relocate polling places away from the most vulnerable facilities. Boards should adjust traditional staffing plans to account for less poll worker recruitment and apply any resources saved to boosting absentee and early voting processing capacity.

As sites are evaluated through this lens, resident voters of impacted facilities must be proactively offered viable alternatives to vote. Cleaning and preventive measures should comport with the CDC Guidance on preventing transmission at polling places, including the spacing and cleaning of equipment and high-touch areas, the use of protective gear by poll workers and provision of hand sanitizer and single-use instruments to voters. The U.S. Election Advisory Commission has also issued cleaning guidance for election equipment.

With regard to expanding and scaling vote-by-mail, the governor's new executive order is a great start, but the state Legislature should return to Albany this spring and codify a public health exception. In March the governor had signaled his approval for such an expansion in his Executive Order 202.2 as a result of COVID-19 concerns. The order permitted any voter to vote by mail “due to the prevalence and community spread of COVID-19” such that “temporary illness...shall include the potential for contraction of the COVID-19 virus” and made accommodations to streamline the application process slightly by allowing voters to apply by email or fax.

In anticipation of conducting 2020 elections in this manner, the bipartisan leadership of the Erie County Board of Elections modified its absentee ballot request form, but uniformity here is highly preferable. Beyond merely extending and expanding this order, policymakers and boards need to use this time well to responsibly address several voting rights concerns and administrative feasibility issues.

To expand vote-by-mail opportunities effectively and fairly, the State should cover the costs of return postage for applications and ballots so voters are not forced to buy stamps. Because New Yorkers have not traditionally voted by mail, they should be invited and encouraged to do so for the duration of the COVID-19 emergency. From there, things get more complicated.

Policymakers in New York have been exploring the feasibility and legality of providing every voter with an absentee ballot without the need for a request, as five states do. But those systems were built and scaled up over time, require significant state resources and advanced planning, and are not a panacea embraced by all communities. Indeed, the Brennan Center for Justice argues that “in-person voting options consistent with public health must also be maintained.”

At a minimum, the county boards should be directed to include notice about a vote-by-mail alternative ahead of each election event. Administrators should streamline ballot requests, a multistep process that often involves two or more snail-mail exchanges. To do so, boards should mail registered voters a postage-prepaid application form with a notice about the upcoming election as well as a link or QR code to permit submission of requests online as an alternative. These methods may permit boards to extend the deadline to request a ballot, and all completed ballots should be counted so long as they substantially comply with formalities and are postmarked by election day, dropped off at polling places, or curbside at the BOE and other convenient locations. Envelopes should be self-adhesive or voters could be instructed not to lick them.

Under such an approach, inactive and recently-purged voters should be sent the mailer as well, along with an affidavit (provisional) ballot if they do apply. Careful, health-based accommodations will be needed for ballot delivery to facilities housing vulnerable residents.

Other traditional voter protection considerations, like safeguards for persons with disabilities and language assistance for New York’s diverse communities take on new dimensions as more New Yorkers vote by mail, as does the absence of a tracking system for mail ballots and ballot requests. These are not new or hypothetical concerns; boards need to work hand-in-hand with the Post Office to address them.

For many reasons, expanding vote-by-mail represents part of the 2020 equation for shifting turnout density away from Election Day, along with early voting. Fortunately, New York’s early voting law took effect in 2019 and will be available to all voters across the state for nine days this June and this fall, for at least 60 hours. Most counties allow voters to cast a ballot at any site. Localities can always provide more early voting locations and hours than the law requires, and in 2019 eighteen localities large and small, urban and rural, red, blue, and purple did so for the convenience of more than a quarter-million New Yorkers who voted early. Let’s build on that success.

Long before there was COVID-19, it was obvious to most New Yorkers that directing millions of us to an assigned poll site on the single Election Day was poor policy that placed undue stress on administrators while creating hardship and disincentive for voters. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy provided another reason to avoid placing all our democratic eggs in one basket.

Enter COVID-19, and the withering arguments against early voting—against de-densifying crowded Election Day poll sites by spreading voter turnout across time and space seem ridiculous. And yet there is concern that some administrators who were lukewarm about early voting to begin with may refuse to lean into these programs now, and instead attempt to contract them.

As daunting as some of these challenges may seem, few of them are actually new. What is new is the public health emergency, the directives to social distance, and the widespread consensus in favor of remedial actions like those discussed here. Moving in this direction would increase access, fairness, uniformity, and predictability for voters, administrators, campaigns, and officials.

Doing so now, well in advance of upcoming contests, will provide administrators with as much lead time as possible to plan and scale up capacity for increased vote-by-mail processing; will provide campaigns with clear rules before they finalize voter mobilization and turnout strategies; and will allow community-based organizations to educate the public about the changes. Together we can protect public health and exercise our rights, but the time for the State to act is now.

***

City Council Member Ben Kallos represents parts of Manhattan. Jarret Berg is the co-founder of Vote Early NY. On Twitter @BenKallos & @JarretBerg.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.