(photo: Darren McGee/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

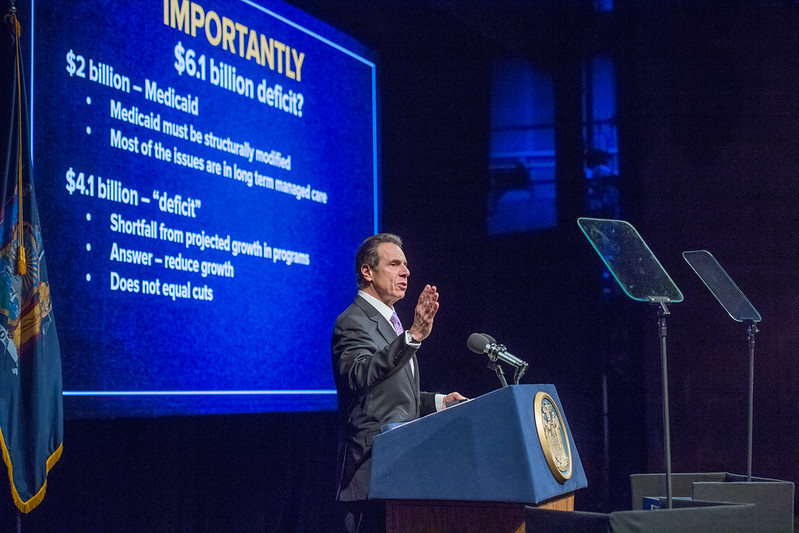

Albany chatter in anticipation of Governor Andrew Cuomo’s 2020 State of the State message was dominated by the prospect of a $6.1 billion budget gap. How to fill it? Tax? Cut programs? All unpalatable.

Of course, budget gaps are nothing new. In an opinion essay published in the Rochester Beacon just three days before the governor spoke, his Budget Director Robert Mujica pointed out that annual “baseline gaps” are routinely closed by controlling spending growth. “Last year,” Mujica wrote, “the baseline gap we closed was $5.3 billion; in recent years it has ranged from $3 billion to $4 billion.”

Three things were new this year though: the gap’s size, its source in a massive area of the budget previously thought to be under control, and its potential for future rapid growth if left unaddressed.

When he finally got to the subject, well into his more than hour-long message, Governor Cuomo attributed the budget gap “largely to our Medicaid cost.” Medicaid in New York will cost $73.8 billion in the current (2020) fiscal year, combining federal and state monies, because Cuomo said, of “federal cuts and…cost increases incurred when local governments were held harmless by the state for Medicaid increases.”

The governor did not mention that New York State remains unique in the nation in the degree to which it required its 57 counties and New York City to help pay Medicaid costs from local source revenues. According to a 2017 National Association of Counties report, “Counties contribute to Medicaid in 26 states. Of these, 18 mandate counties to contribute to the non-federal share of Medicaid costs.” But no state’s counties pay more than New York’s, “$7 billion per year – or $140 million per week.”

Nor did Cuomo mention that the property tax cap, which constrains counties’ ability to meet the costs of their Medicaid share, was enacted at his initiative.

Nor did he mention that this year’s budget gap was widened by rolling forward a far greater amount than usual in state Medicaid spending - $1.7 billion - from the 2019 to the 2020 fiscal year, in order to stay under another cap, the Medicaid Global Spending Cap, created in 2011 by the state to keep these costs in check.

In Cuomo’s first term, and in part of the second, per enrollee Medicaid costs were cut, and then held in check even as the covered population grew by over 1 million people – a stellar achievement by the governor’s Medicaid redesign team. But cost growth resumed in 2017 and thereafter, and absent decisive intervention, is projected to continue growing at an unsustainable pace.

The Budget Division’s mid-year update to the state’s 2020 financial plan attributed Medicaid spending increases to two policy choices: the aforementioned state assumption in the growth of the local Medicaid share and the phased-in increase in the state minimum wage to $15 per hour in some parts of the state, enacted in 2016.

“The FY 2019 State Operating Funds spending increases include over $900 million for the incremental cost of the local Medicaid growth takeover,” the Budget Division wrote, “and nearly $800 million for the direct cost of the minimum wage increase to health care providers,” which is passed along to the state and the localities. While the first was highlighted by the governor in his speech, the second, a key achievement highlighted during the 2018 campaign for governor, went unmentioned.

Medicaid is administered in New York State through the counties and the City of New York. In the governor’s view, now that these localities have less skin in the game, an unintended consequence is that they have less incentive to seek efficiencies. “You cannot separate administration from accountability,” Cuomo said in the State of the State. “It is too easy to write the check when you don't sign it.”

Of course, even with some of the financial pressure relieved, the counties and New York City are still left with a big aggregate obligation; for 2019 it totaled $7.2 billion. Moreover, a major element of Medicaid reform, authorized by law in 2012, has been to “transfer responsibility for the administration of the Medicaid program from Local Departments of Social Services to the [state] Department of Health.” Significant progress in achieving this goal, and plans for future steps, were documented by the state Health Department in a report to the governor and Legislature in December 2018.

Following up in his January 21 budget message this week, Governor Cuomo revealed how he proposes to link writing the check with paying it. The state would continue to cover the increase in local share it had assumed, but only if New York City and the counties stayed annually within the 2 percent property tax cap and limited their yearly growth in Medicaid costs to 3 percent. If they go over this annual growth rate, they would pay the difference. If they went under, they would share the savings. (Cuomo is also empaneling another Medicaid redesign team, tasked with finding $2.5 billion in savings.)

All this assumed, of course, that actual control of the level of spending for Medicaid is in local hands. Even though more and more of the administration of Medicaid, as a matter of state policy, is in the state government’s hands. Even though demand for services might rise because of changing social or economic conditions, entirely outside of local control.

There is another way to cut the Gordian Knot. It is precisely to incentivize efficiency and accountability that reformers have long advocated full state government assumption of responsibility for the Medicaid program. For example, the Citizens Budget Commission wrote in a 2018 report: “It is time for New York to adopt measures that will completely eliminate the required local share of Medicaid.” This very good idea would achieve precisely what the governor is advocating.

Where would the money come from? In many jurisdictions increased sales tax authority was authorized for localities to pay for Medicaid. With no Medicaid obligation to meet, New York City and the counties could be required to relinquish some of this resource.

Thus a big tradeoff: counties would be relieved from responsibility for administering Medicaid and paying any share of the program’s costs. In return, the state would reclaim that portion of local sales tax revenues required to cover localities’ former Medicaid share.

This would fully make one government, the state government, both the “check writer” and the “check signer” for all of Medicaid. And the governor would then have the full control he needs to achieve the economies he thinks possible but unachievable under the current shared responsibility for the program.

***

Gerald Benjamin is director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz. On Twitter @TheBenCen.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.