(photo: the governor's office)

MTA officials acknowledged at their June 2019 board meetings that the agency is borrowing money to be repaid through a New York State law that promised to have the State of New York provide the MTA $7.3 billion once the authority had exhausted its own funds on spending for the current five-year capital program.

The 2016 state law was merely an “IOU," there had been no specific source of funds identified for how the state would pay the money, nor has there been any plan developed since enactment in the state budget that year.

The state's total commitment was $8.6 billion, including some new capital funds it added as part of the newer Subway Action Plan and other promises, which to date have provided about $1 billion in actual funds. It is the $7.3 billion IOU that is still outstanding. New York City was also required to provide $2.7 billion to the agency as part of a mutual obligation with the state. The city has provided about $800 million to date.

These commitments refer to the current 2015-2019 Capital Construction Program, not the 2020-2024 Program to be released in a few weeks by the MTA. That new program, not yet adopted, will have its main funding coming from the congestion pricing system passed earlier this year, with revenue from the tolls scheduled to begin in 2021.

The elements of the 2015-2019 MTA Capital Program were patched together in the 2016-2017 state budget (a year late), my final year in the State Assembly while I was still chair of the Assembly Committee on Corporations, Authorities, and Commissions. The full 2016 package that became the Capital Program was about $30 billion; some $3 billion has been added since I retired. The MTA Capital Program Review Board adopted the plan in 2016 shortly after the budget was enacted.

The question of the state’s outstanding commitment to the MTA capital program, written into the law as the last dollars to be spent in the overall plan, has been the source of limited scrutiny, but is now in the spotlight as the IOU comes due and the next capital program is designed.

At the June 26 public meeting of the MTA Board Finance Committee, finance chair Larry Schwartz and board member Veronica Vanterpool expressed concerns about an agenda item authorizing the MTA to borrow an extra $2 billion to fund the capital program.

Per the minutes of that MTA Finance Committee meeting (page 12):

"Ms. Vanterpool voiced her reservations about increasing the amount, noting that there is that $7.3 billion commitment from the State that has not been received, as well as the commitment from the City. Mr. Foran [the MTA's Chief Financial Officer]... noted that the commitment from the State is predicated on MTA to spend MTA dollars first and that MTA is already beginning to commit against the State's portion (about $2 billion commitment, with some expenditures already incurred) and the State has agreed to that.”

The discussion continued (page 13), "Mr. McCoy [MTA Finance Director] commented that regarding the State funding, the $1.2 billion in BANs [bond anticipation notes] were issued in two components; $1 billion for MTA funded projects, and $200 million is designated for the projects under the State Commitment. Mr. McCoy stated that it was clearly communicated with the State that, when the notes are due, the State will need to provide the funding."

The MTA Board proceeded to add the $2 billion in new borrowing at its main June 26 board meeting two days after this finance committee discussion. State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, in an August 7 report on New York City's financial condition, stated (on page 34), "According to the MTA, it has committed all of its capital resources and has begun to commit up to $3 billion against the State's obligation. Consequently, the MTA will require funding from the State beginning next State fiscal year (2020-21) to cover the cash cost of these capital commitments"

Where Will The Money Come From?

The question now is: How will the state meet this new commitment in the coming budget?

The state has the option of itself providing the MTA the money directly, or creating a stream of funding for the MTA to enable the agency to secure the borrowing of the funds, or some combination thereof. But there are serious challenges, the first of which is that 2020 is an election year for the state Legislature.

To enable the MTA to borrow $7.3 billion, a revenue source, i.e. another tax, would need to provide the authority about another $400 million a year. Does the Legislature want to do another tax increase in an election year? Maybe 2021, not 2020. Seven of the eight new Democratic State Senators that won the Democratic party the majority come from the New York City suburbs. Four of these seven suburban races were super-close, with the Democrats winning by just 2-3 percentage points, or even less.

Several other races were won by less than ten points. Many of these newly-minted legislators could be uncomfortable voting for another tax increase for the unpopular MTA, after voting this year for congestion pricing, a real estate transfer tax surcharge, and internet sales taxes. They are already likely to face Republican attacks in the election for these votes.

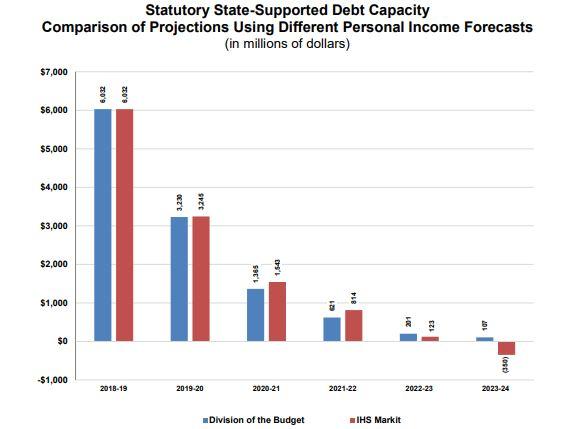

The state's ability to borrow the funds directly (the MTA does not need all $7.3 billion next year, but over several years) is also severely constrained by limits on the state government established by the Debt Reform Act of 2000. This law limits state-supported debt to 4% of the state's total personal income from the preceding calendar year. The following chart from a July 2 state comptroller report on the 2019-2020 budget shows how the state's capacity to borrow is dwindling.

Next year the state's ability to borrow funds in support of the entire state budget and the entire capital program will be limited to about $1.36 billion and by 2023-24 will be nonexistent. Borrowing for the MTA would be competing with roads and bridges, water and sewer, the state and city public university systems, mental hygiene, and the environment. Little could be anticipated from this source given the constraints.

Another possibility would be for the state to provide the MTA money from the financial industry settlement windfall. Some $2.6 billion is available in 2020-21 from this source, but, once again, the MTA would be competing with upstate economic development commitments, Javits Center and transportation commitments, and general budget relief. But Governor Cuomo and the Legislature could make several hundred million dollars available from this source -- once again, very limited, given the competition for other funds.

Of course, the Legislature could do a tax/fee hike in 2021, even something as simple as extending the for-hire vehicle surcharge on Uber and Lyft to trips with outer borough destinations or adding to the Manhattan business district price. But it is a tax increase of sorts.

Late in the 2015 legislative session, as we struggled to deal with funding the 2015-2019 MTA Capital Program, I worked with MTA senior officials to introduce legislation to provide the MTA a new source of money without a tax increase. The bill provided for a staggered diversion of existing personal income tax revenue from the MTA region over a four-year period to enable the MTA to borrow what was viewed then as $6-7 billion, providing about $400 million a year in revenue to which the agency would be entitled at the end of four years.

Growth in the state's personal income tax revenue would now bring in about $500 million a year under the formula in the bill (A. 8227-a from the 2015-2016 session), so the percentage amount in the old bill could be shaved.

The critical concept of the bill was that it statutorily entitled the MTA to the revenue, enabling it to borrow the money itself and not be a debt of the state subject to the Debt Reform Act and the limits on the state’s capacity to borrow. As written, it would start in the first year with a small three-tenths of one-percent diversion of PIT revenue in the region to the MTA , reaching 1.2% in the fourth year. Each year's revenue piece was separated in a schedule pursuant to law, so if a recession hit, the state could suspend the following year's diversion and preserve revenue in the general fund.

The governor and the Legislature should continue to examine this concept, which was believed to be workable by MTA officials at the time, though viewed by senior Assembly Ways and Means staff as just not needed. But the $7 billion IOU has come due.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.