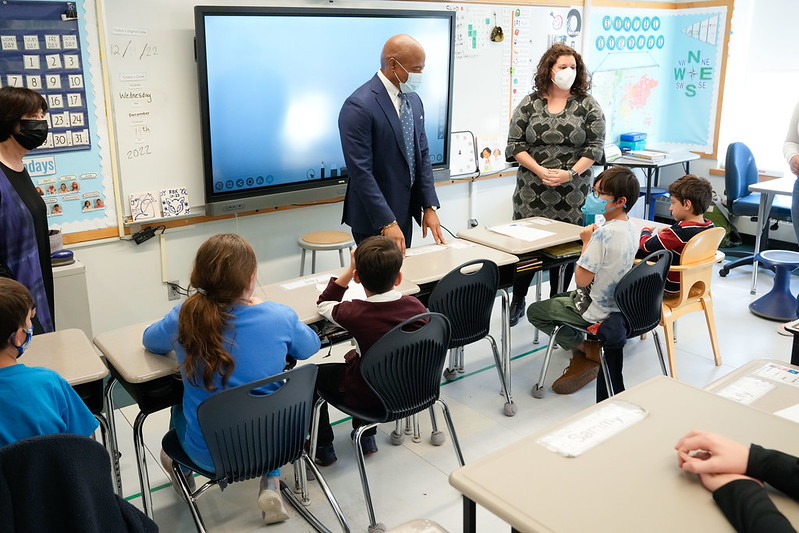

Mayor Adams at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

One profound outcome of COVID-19 has been the consensus among government and school system leaders of the urgency of getting more social workers in our schools – and in particular stemming the shortage of mental health resources for children in communities of color. This week’s New York State Assembly Education Committee hearing reinforced the need to redress the impact of a life-changing event on the educational and social development of our young people.

Research from the nonprofit organization NWEA revealed just how deep and disparate the pandemic era learning losses have been for children who were already struggling, and now are finding it harder to catch up. This amplified the National Assessment of Educational Progress report on the precipitous decline in math scores, especially for lower-income Black and Hispanic students who tended to have more remote learning, and less technology and human support, than their higher-income peers.

This fall, New York City’s Department of Education made a bold first step towards building a healthier ecosystem as young people return to a post-COVID “normalcy.” With the goal of evaluating students’ social-emotional strengths and challenges, it trained teachers to use a widely-recognized tool, called the DESSA (Devereux Student Strengths Assessment), to ask the right questions about how their students are coping with relationships, self-awareness, and decision-making.

Yet many New York City students — especially those in economically insecure diverse neighborhoods who disproportionately lost a parent or primary caregiver to covid, or the 100,000 who experienced homelessness in the last year — are not going back to pre-covid lives. They have experienced a level of trauma that calls for the professional skills of social workers.

Our city’s teachers – already mainstays for our children – are stretched thin trying to achieve academic outcomes. They are not clinically trained to address these underlying conditions nor the complexities of toxic stress, which is the neurological response to continuous trauma that shuts down a child’s ability to learn and socialize.

This kind of stress can also emanate from other inequities linked to systemic racism, such as lack of access to medical care, nourishing food, or clean air and water. These are among the many factors that landed the Bronx at the bottom of the County Health Ranking in New York State – number 62 of all 62 counties, according to a new study funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which advocates for a landscape of health equity strategies nationally.

Taken together, this is an urgent call for a next tranche of strategic investments in the mental health and wellness of our most vulnerable children.

Let’s look at what this means from a child’s perspective. If they are hungry, how are they going to be able to learn? If they experience trauma, how can we expect them to “self-manage” or get along nicely with peers? The risks are that they will act out, miss class time, feel alienated, and not want to be at school at all.

As a 115-year-old nonprofit that provides in-school social workers for 30,000 K-12 students in 67 schools across the city, we know that kids don’t get to choose their environment. But they can benefit from a trusted adult who can help them sort out their experiences.

A young woman, who we will call Keisha, was struggling with her identity as an adopted child. During her first year in high school, her grades were slipping, she was cutting classes and was hanging out with friends who reinforced her slide. When the covid shutdown hit that year, she felt alone and angry at home. Her parents, loving relatives, were alarmed but couldn’t get her back on track. With the professional sounding board of a social worker who worked with her first remotely and later in person, Keisha built the skills to make her own decisions and change her behavior. When she returned to in-person school, she shed her old crowd and formed a few healthy friendships. Today as a senior, she has stellar grades and has already been admitted to two colleges.

In short, this approach works. A recent survey of our middle and high school students found that 87% have relationships with adults who care about them, cultivating resilience; 80% get the space and support to honestly share what they are feeling and thinking, the basis of agency; and about 75% said that our work with them supports their academics, helping them stay in school.

Parents and teachers agree: 96% of parents said our counseling helps with their children’s social and emotional needs; and 91% of teachers said our work makes their classrooms easier to manage.

Right now, though, the city is facing a perfect storm in funding all these services. Reduced student enrollment numbers affecting budget allocations and competing priorities threaten to diminish resources for our at-risk children, precisely at the time they need them most.

It’s going to take not just government, but also private funds to tackle this confluence of issues. All New Yorkers will benefit when our next generation is healthier and better prepared to succeed in society. It’s a landmark moment. Our children, and our city, deserve the chance.

***

Wesner Pierre is CEO of Partnership with Children. On Twitter @PWCNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.