Housing in view (photo: Governor's Office)

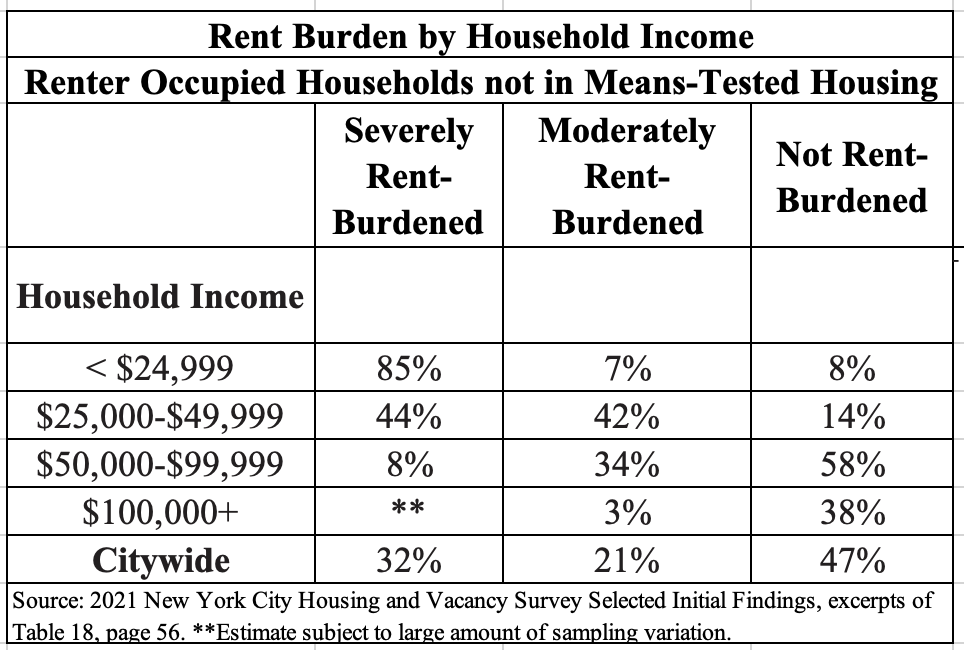

It is easy to focus on New York City proper when thinking about the affordable housing crisis. Initial findings from the city’s triennial Housing and Vacancy Survey, for example, show that 32% of all city renters not living in means-tested housing are severely rent-burdened, meaning paying more than 50% of household income for rent. It’s 85% for households with income of less than $25,000.

But, as New York City Mayor Eric Adams prepares to release his housing plan – building on an outline of proposed citywide zoning amendments he recently presented and other elements his appointees have offered – we cannot continue to ignore the regional dimension to that crisis.

More than 50 years ago, the Regional Plan Association issued a report on housing opportunities in the New York City region, noting in 1969 that there was “growing apartheid” and a “severe limitation” in the suburbs on housing available to members of minority groups. The report further referenced the fact that there was disproportionately little affordable housing in the suburbs and that the growing apartheid system “placed a severe and unfair burden on local governments [most notably New York City] which are left with inordinate costs resulting from poverty.”

Fast-forward to the present. According to 2020 Census data, there are still in Westchester at least 16 towns and villages that have Black populations of less than 3%. Along with the racial segregation, the disproportionate costs borne by New York City as compared with its neighbors in respect to providing both affordable housing and social services remains as well.

Using 2020 five-year American Community Survey data compiled by Social Explorer, I found that only 13.1% of the combined households in Westchester, Nassau, and Suffolk had household income of less than $30,000; by comparison, the percent of New York City households with household income of less than $30,000 was 26.1%.

In other words, the percentage of New York City households defined as “extremely low income” is double that of its suburban counterparts. (At the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of suburban households with household income greater than $150,000 was 34.7%, significantly higher than the 20.1% of New York City households that met that criterion.)

So for all the ideas about what to do about affordability within New York City – including some recent ones of my own – it is important not to forget the critical role that New York’s suburbs are supposed to be playing in providing a fair share of regional affordable housing need.

Despite their acting otherwise, New York City’s suburbs are not beyond the reach of state law (which has long required that each municipality plan for its share of regional housing need). They are not supposed to be beyond the reach of federal law, either. The Fair Housing Act makes exclusionary zoning – like those suburban zoning codes that preclude the building of multiple-family, mixed-income housing – illegal.

Yet these suburbs have, for decades, defied state and federal law and failed to build much housing. From 2010 to 2020, for example, the Regional Plan Association calculates that Nassau and Suffolk Counties had fewer than 10 building permits issued per 1,000 residents, and that Westchester clocked in at only 13.5. Manhattan housing starts per 1,000 residents – inadequate still – were a much higher 30.1.

One notable recent example of the active suburban resistance to building affordable housing is found in the fate of the landmark housing desegregation consent decree that the Anti-Discrimination Center won against Westchester in a case brought under the federal False Claims Act.

The consent decree entered in the case had, according to a brief filed by several fair housing organizations, “provided more opportunity to effect significant structural change in hyper-segregated residential housing patterns than any other legal proceeding in the last 25 years.” Ultimately, though, the decree had to be enforced by the federal government and its monitors, who were unprepared to do so. They snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by failing to have the political will to overcome the county’s resistance.

Even more recently, New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed early this year what she described as “sweeping plans” to address the housing affordability crisis, including zoning changes to allow accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods and to override local limits on multi-family, transit-oriented development. These zoning initiatives quickly ran into intense suburban opposition, and were dropped from Hochul’s budget proposal.

New York’s Department of City Planning would appear to understand at least on some levels that the city’s housing needs exist within a regional context, but the city’s leadership has never done more than engage in a “pretty, please” approach to seeking regional equity (to be honest, it is not even clear whether city leadership has gone as far as “pretty, please”). The failure of New York City’s suburban neighbors to build their fair share of affordable housing not only hurts their own residents, that failure contributes significantly to New York City’s affordable housing crisis as well. And the failure of the city to press its neighbors to do more has been a grave error.

The city should open its eyes, exert real political will, and be prepared to use all the tools it has available – including state and federal legal tools that I am confident would be successful – to bring affordable-housing “fair share” to the metropolitan region.

***

Craig Gurian is executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center, based in New York City. On Twitter @antibiaslaw.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.