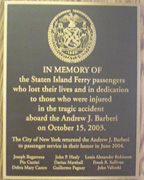

It is easy to miss the small plaque on the wall of the ferry honoring the people who died in a terrible accident on October 15, 2003. Repaired and back in service, the Andrew J. Barberi looks like the other eight Staten Island ferries, but it was the boat that failed to slide into its usual slip and instead crashed into a concrete pier. Eleven people died and 165 were injured. The captain on duty had been overmedicated and passed out as the boat charged full-speed into the pier.

Repaired and back in service, the Andrew J. Barberi looks like the other eight Staten Island ferries, but it was the boat that failed to slide into its usual slip and instead crashed into a concrete pier. Eleven people died and 165 were injured. The captain on duty had been overmedicated and passed out as the boat charged full-speed into the pier.

Three years later, while the ferry trudges dutifully back and forth on its 25-minute journey from Lower Manhattan to Staten Island, it remains a continuing and costly drama for those involved – including City Hall.

Crime And Punishment

The criminal cases have been settled. Federal prosecutors used an obscure 1838 maritime law known as seaman's manslaughter to charge both the pilot and the director of ferry operations. It is the same law that was used to prosecute executives when an excursion boat in the East River sank, killing more than 1,000 people. That happened in 1904, which was the last time a vessel in New York waters killed or maimed a large group of people – until the Andrew J. Barberi.

Richard Smith, the pilot who passed out at the helm that day, is incarcerated. Right after the accident, he had attempted suicide twice but failed. He pleaded guilty to 11 counts of seaman's manslaughter and making false statements. He is serving an 18-month sentence.

Richard Smith, the pilot who passed out at the helm that day, is incarcerated. Right after the accident, he had attempted suicide twice but failed. He pleaded guilty to 11 counts of seaman's manslaughter and making false statements. He is serving an 18-month sentence.

The ferryboat captain, Michael Gansas, was in the outbound wheelhouse doing paperwork during the crash. Prosecutors said that since the two-pilot rule was not enforced at the time of the crash, Gansas would not be charged with a crime. Since Gansas ducked investigators right after the accident, the city fired him. He sued the city for reinstatement but lost.

The director of ferry operations at that time was Patrick Ryan. He is in prison for not enforcing the rule requiring that two qualified pilots be in the wheelhouse at all times. He pleaded guilty to seaman's manslaughter and making a false statement to investigators and is serving a sentence of a year and a day at Allenwood Federal Correctional Complex.

Smith's physician, Dr. William Tursi, had hidden evidence of the pilot's medical problems and use of medication. He received probation, six months of home confinement and 300 hours of community service. His license to practice medicine was suspended.

The port captain, John Mauldin, who is Ryan's brother-in-law, received two years' probation for making false statements to investigators.

A crewmember, mate Robert Rush, was in the wheelhouse with the pilot, but didn't see the blackout. Officials suspended him from his job after he failed to show up for a meeting with investigators.

City Liability

Rulings are still pending on some of the issues that will affect how outstanding victims' claims will be settled. City attorneys have tried some odd arguments in court to limit liability. The accident involved an act of God because of the captain's medical condition. That would absolve City Hall of responsibility for some damages. The city government’s court filings also present seemingly contradictory blame of "intentional misconduct of Captain Smith…and the negligence of Mate Rush." That would mean that the crew was responsible, not the city (in the form of supervisors).In addition, attorneys argued that maritime law limits the amount of compensation to the cost of the vessel. That would be $14 million (though settlements already made have exceeded that amount).

Victims argued that ferry rules mandate two licensed pilots in the wheelhouse during docking. Federal prosecutors found two printed rulebooks—from 1908 and 1958—that list the two-pilot rule. If the rule was clearly on the books, the city may have to pay out much more to victims.

The city even paid for the (unsuccessful) defense of Patrick Ryan, the director of ferry operations, saying he was unfairly prosecuted for seaman's manslaughter. Criminal conviction of the ferry official (not just the personnel on board) could mean the city will be held responsible in civil suits by victims.

The city also paid for lawyers for 52 other city employees.

The city has settled 110 claims with $16 million so far with widely varying amounts. The largest settlement so far, $8.9 million, has gone to Paul Esposito, a waiter who lost both legs in the accident. William Castro, whose 39-year-old wife Debra died of injuries two months after the accident, received $3 million. One injured passenger got more than $1 million, and another received $500.

Another 81 victims' claims are pending. All the claims together total $3.2 billion.

Another lawsuit demands $8 million from the city for a tugboat that assisted the ferry. Immediately after the crash, the Dorothy J chugged over to the ferry, helped get the boat into the slip and held her steady for 68 hours. Maritime law allows the operator of such a vessel to claim compensation.

Other expenses for the city include nearly $7 million to repair the ferry and $1.4 million to repair the damaged pier. The city has also paid almost $4 million to outside attorneys.

Rules and Crews

Some 30 accidents caused by carelessness or lapses in judgment have marred the generally reliable service in recent years, according to an examination of records by the New York Times.

The most damaging accident before the Barberi crash happened in 1978, when a ferry rammed a seawall, injuring 200 people. In 1963, a ferry sank. While those and other accidents were serious, none caused fatalities. Many incidents could have been prevented with more vigilance by the crew, investigators found. But few procedures changed over the years.

Now, because of the deaths in the Barberi accident, rules for running the ferries have been firmed up and are more likely to be taken more seriously. In 2004, new regulations mandated more staffing on the boats, background checks, a strict drug and alcohol policy, more stringent medical exams for employees, surveillance cameras on board, better signs, and communication with fellow crewmembers.

There were always supposed to be two people capable of driving the boat in the wheelhouse. In practice, few ferry operators had ever followed the rule. Now the rules are more explicit. Three people are required, two of them pilots.

The ferry operation had been criticized for cronyism and nepotism. A change in management is meant to change that culture. Less than a year after the crash, James DeSimone, a graduate of the State University of New York Maritime College and a former vice president of a tugboat company and of New York Water Taxi, became the new chief operating officer.

There are questions about why the ferries are run by the city Department of Transportation and not by the state-run Metropolitan Transit Authority, as all the other city public transportation is. "We think it needs to be integrated into the public transportation system as a whole," Carter Craft of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance told the Daily News.

Anachronistic Transportation

The city took over ferry service in 1905. It was—and still is—the only direct way to get from Staten Island to Manhattan. It seems like an anachronism in such a big city, to rely on boats to carry vast numbers of commuters. But only the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge provides a faster direct method of getting from Staten Island to other boroughs (specifically to Brooklyn). Two bridges carry vehicles to New Jersey. After 9/11, motorized vehicles could no longer travel on the ferry. The ferries remain an essential service for commuters.

The service runs 110 times a day, transporting 65,000 people. That adds up to some 19 million people a year. That would be a massive public transportation system in most cities. In New York, where people take 7.1 million subway and bus rides in the city every day, the ferry represents a small program.

Since 1997, the service has been free. It was too complicated to integrate into the new Metro Card system, said Mayor Rudolph Giuliani at the time.

Today, rebuilding and remodeling of the terminals at both ends have made the trip more pleasant. Renovations replaced the grubby terminals with shiny new structures more welcoming to commuters and tourists.

The Manhattan side features a glass-fronted building with a big blue neon Staten Island Ferry sign. Inside, but still visible from the street, the words from the familiar Edna St. Vincent Millay poem unfold across the room: "We were very tired/We were very merry/We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry."

With the long open wooden benches inside, the $2 beers and the magnificent views of the Statue of Liberty, Lower Manhattan and the boats in the harbor, the free ride is an appealing jaunt for tourists as well as an essential ride for commuters. Senator Charles Schumer found out just how appealing the ride is for visitors when he campaigned for reelection in 2004. He rode the ferry one day, shaking hands with everyone who was awake. "Hi, how are you? Where are you from?" he'd ask. England, France and Iowa were some of the answers that day. He chatted and quickly moved on, looking for constituents. After awhile, he turned to an aide, and sounding frustrated, said, "They're all tourists."

The tourists and the commuters (the commuters were probably the sleeping people that Schumer knew better than to wake up) know that despite the harrowing events just three years ago, and with more strict attention to safety, the Staten Island Ferry remains an integral part of the city's day.

Related Web Sites:

Staten Island Ferry, from the Department of Transportation Staten Island Ferry History, Facts

Â