|

On the brink of its fortieth birthday, the landmarks preservation law – created two years after New Yorkers were shocked at the needless demolition of the old Pennsylvania Station in 1963 – has preserved more than 1,100 individual landmarks and 22,000 properties in 81 historic districts across New York City. Thanks to the law, and the efforts of the city’s preservationists, New Yorkers and visitors to the city can enjoy brownstone-lined streets of Brooklyn, garden communities of Jackson Heights and such indestructible-seeming architectural monuments as Grand Central Terminal, all of which might not otherwise exist.

Today, preservation is a proven tool for stabilizing and revitalizing neighborhoods, maintaining a record of New York’s architectural and cultural history, and creating a tangible link between past and future generations.

But while 40 years of landmark preservation is indeed cause for celebration, many preservationists are not in any mood to pop open the champagne. Communities throughout the city are increasingly frustrated by the agency created by the law, the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which seems out of touch with our concerns.

A coalition of civic organizations has produced a report, Problems Experienced by Community Groups Working with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, (in pdf format) that cites nine problems with the commission and proposes several avenues for reform. The report was submitted to the City Council’s Subcommittee on Landmarks, Public Siting and Maritime Uses, which scheduled a special oversight hearing for November 29 at 10:00 AM.

Among the host of reasons for communities' concern is the commission’s failure to hold public hearings on such buildings as 2 Columbus Circle and St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Harlem, both imminently threatened with destruction or a destructive alteration. These two -- one a mid-century Modern icon by one of America’s most progressive Modernist architects, Edward Durell Stone; the other a work of both architectural and spiritual importance to the Harlem community -- are what Penn Station was forty years ago: igniters. This time, however, the city has a Landmarks Law. The question is, why isn’t it being used?

One reason is money. At just over $3 million, the Landmarks Commission’s budget is the smallest of any city agency, and it has fallen precipitously over the past decade, with the staff being cut back significantly. Meanwhile, the commission’s workload has increased by volumes. In any given year, it receives close to 8,000 applications for alterations ranging from cornice replacements to entirely new construction. And with each designation of an individual landmark or district, the workload increases.

But, while money is tight, the city cannot afford in architectural and cultural terms to force the agency to scale back its efforts. The mission of the agency is to protect the city’s historical and architectural heritage. Once this heritage is gone, it is gone forever.

Another reason the landmarks law isn't being used is politics. The decreased funding for the Landmarks Commission is not merely a symptom of across-the-board municipal belt-tightening. It reflects the city’s priority list, with the real-estate development lobby right at the top. The bias towards large-scale development, which promises quick fixes to perceived urban problems, versus preservation, which can be a slower, more organic renewal process, has an impact not only on the budget but on the political dynamics determining which buildings do – and do not – get considered for landmark protection.

Although 2 Columbus Circle is by no means the only source of preservationists’ concern (why else would dozens of groups in communities as varied as St. George in Staten Island and the Upper East Side of Manhattan have leapt to endorse the coalition's report?), it provides a useful case study.

The Case For 2 Columbus Circle

|

Robert A.M. Stern is one of the most vocal supporters of preserving 2 Columbus Circle. His credentials go beyond his role as foremost chronicler of New York’s history (Stern is the author of New York 1960, New York 1880, New York 1900, New York 1930, and a forthcoming volume entitled New York 2000). He is one of the most famous architects in the United States, the former director of Columbia University’s acclaimed graduate program in historic preservation, and the current Dean of the Yale School of Architecture. When considering whether to designate a particular resource as an individual landmark or as part of a historic district, the Landmarks Commission frequently cites Stern’s opinions as proof of the resource’s significance. In terms of New York City landmarks, he is clearly an authority.

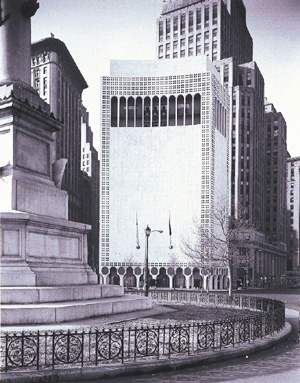

The campaign to save 2 Columbus Circle began in earnest in 1996, soon after the building turned thirty years old and became eligible for landmark designation, when Stern drew up a list of “35 Modern Landmarks-in-Waiting” that was published in the New York Times. Two Columbus Circle, the former Gallery of Modern Art built in 1964 to house Huntington Hartford’s art collection, was included along with the Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Holding a public hearing to consider 2 Columbus Circle’s merits for landmark designation should have been a no-brainer for the commission. Yet, while the commission has moved to designate a few of Stern’s 35, it has determinedly ignored him on 2 Columbus Circle. It has also ignored the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Preservation League of New York State, both of which included 2 Columbus Circle on their latest “Most Endangered” lists. It has ignored New York Times architecture critics Herbert Muschamp (“The refusal of the New York City Landmarks Commission to hold hearings on the future of 2 Columbus Circle is a shocking dereliction of public duty”) and Nicolai Ouroussoff (“Stone’s design, and the people of this city, deserve more respect than this”). The commission appears unmoved by the signatures collected from over 1,000 individuals and every single major preservation organization in the city, including the Municipal Art Society, the Historic Districts Council, and the New York Landmarks Conservancy, calling for a hearing – not official designation, just a hearing.

These advocates are the Silenced Majority, ignored while the new Museum of Arts and Design plans a renovation of the now-vacant 2 Columbus Circle that would destroy many of its distinctive features. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has described those features in this "unorthodox" building as "a marble skin, porthole windows and a street-level arcade that critics have likened to a row of lollipops." But even some critics of the building question the Landmarks Preservation Commission's refusal to give it a hearing.

Recognizing the commission’s delinquency on 2 Columbus Circle as part of a larger pattern of negligence, Stern recently issued a statement urging the City Council to exercise its oversight power, “a move necessitated by the continued failure of the city agency to fulfill its important duties.” He went on, “while reasonable people can disagree over the merits of designation, the reluctance of the Commission to simply hold hearings in the face of sustained, vocal, widespread, and indeed unprecedented demand, including the recommendations of two former Chairs of the Commission, is, frankly, inexplicable.”

The former chairs to whom Stern refers are Beverly Moss Spatt, a planner who served from 1974 to 1978, and Gene A. Norman, an architect who served from 1983 to 1989. Both have written to the commission to call for a hearing for 2 Columbus Circle, as has Anthony M. Tung, a preservation scholar and former Landmarks Commissioner. Tung wrote, “Simply, in the 26 years of my involvement in preservation matters, beginning with my appointment as a commissioner by Mayor Edward I. Koch in 1979, I have never seen the commission turn its back on such a widely supported and substantive argument for a hearing…Have all of these people suddenly grown ignorant? Entered senility? Gone blind? Or is the commission being arbitrary and capricious?”

Arbitrary and capricious behavior by city agencies is grounds for legal action. The report points out that, early in its history, the Landmarks Commission was peppered with lawsuits brought by property owners and developers seeking to overturn the Landmarks Law. Today, a number of lawsuits have been brought by owners and community groups who believe that the commission should have applied higher standards to protect the city’s historic resources. Somewhere along the line, the Landmarks Commission was cast (by its leadership and real estate-lobbied mayoral administrations) in the role of back-room negotiator, transforming what was once a participatory decision-making process into a bureaucratic maze that thwarts meaningful public dialogue. The agency’s ability to determine the future of over 23,000 historic properties throughout the five boroughs has been seriously undermined.

The problems experienced by communities seeking to work with the Landmarks Commission reflect both an economic and a cultural shift in the agency’s operations. To try to debate which shift caused which is fruitless. The point is that the commission’s lack of transparency and responsiveness stymies community-based preservation efforts and leads directly to the loss of irreplaceable historic fabric. This loss and the growing chasm between the commission and its natural allies – the citizen-stewards of the historic city – must not become the legacy of our generation.

Kate Wood is executive director of Landmark West!, a community group currently leading the effort to preserve 2 Columbus Circle.

Â