Muddled, Shifting Messages from De Blasio on Essential Metrics as City Nears 'Reopening'

Mayor de Blasio during a recent coronavirus briefing (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

New York City’s response to the coronavirus outbreak has been a battle on shifting sands. As information about the disease and officials’ recognition of its threat evolved over time, so did the government approach, from initially continuing business as usual well after the first cases in the city were confirmed to a statewide shutdown of sorts and strict social distancing guidelines that have now been in place in New York City for over two months.

But adding to the uncertainty that has gripped the city during this crisis has been a lack of clear messaging from Mayor Bill de Blasio about how the city is doing on key coronavirus-related public health and recovery metrics set by the mayor himself, as well as those set by Governor Andrew Cuomo, who holds ultimate say over the city’s “reopening.”

On April 9, de Blasio announced three key infection and hospitalization “indicators” the city would be tracking to evaluate its progress on the downside of the COVID-19 curve, with goals he said the city would have to meet in order to begin reopening the economy and get people back to their daily lives.

“Now, what do we need to start to discuss moving to the next phase, that better phase and to start to discuss any change, any relaxing of restrictions?,” de Blasio said at the time. “We need to see all three of those indicators move in unison in the same direction. We cannot see two of them get better and one of them get worse. That doesn't work. All three have to move together down; all three have to move in a better direction together. They have to do that for at least 10 days to two weeks -- sustained, consistent. If one day gets good and the next day goes bad, that doesn't count. We need to see a clean, clear pattern that sustains itself for several weeks to then say it's time to even discuss some of the positive changes we'd all like to experience.”

To begin to even attempt to resume some normalcy, de Blasio said, there would have to be 10-14 days of consecutive reductions in hospital admissions for suspected COVID-19, number of people with coronavirus in the ICU in the municipal hospital system, and the percentage of people testing positive for the virus.

But those metrics did not account for the possibility of slight day-to-day upticks amid overall positive trendlines, and other than on Fridays the mayor was not showing any larger picture at his daily public briefings, where he focused only on the day-to-day change. De Blasio presented updates on whether the daily numbers on coronavirus hospitalizations, public hospital coronavirus ICU patients, and positive COVID-19 tests were up or down from the day before, talking about progress or regress and showing red or green arrows for each of the three metrics based on that day-to-day change, not presenting New Yorkers with the fuller picture.

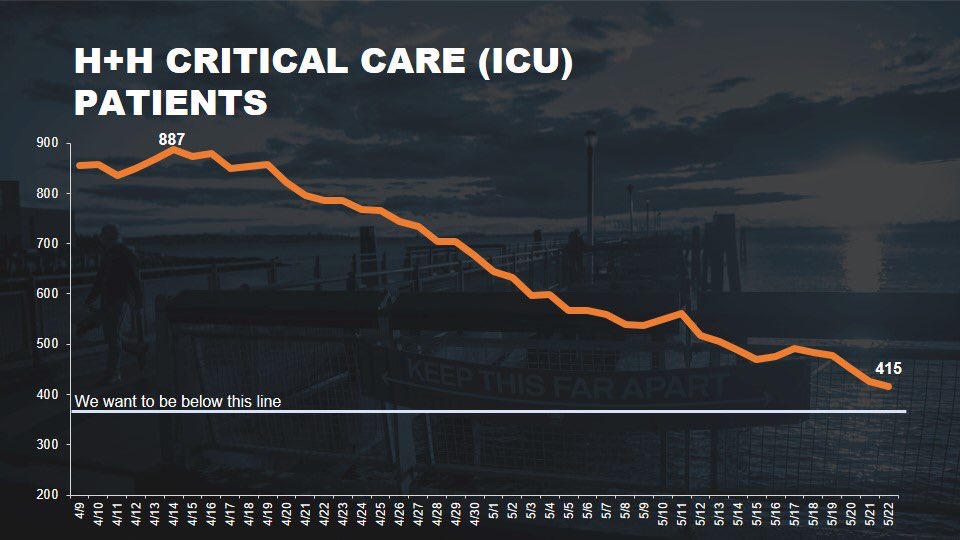

Meanwhile, his health department posted its own version of the mayor’s metrics on its website, with thresholds shown relative to the three “milestones,” as the department calls them but the mayor doesn’t, and graphs with easy-to-understand labels like “We want to be below this line” and notes about “consecutive days” below such thresholds but not of consecutive day-to-day decline.

Adding to the confusion, de Blasio was using hospitalizations across all of the city’s roughly 66 hospitals, but ICU patients only in the city’s 11 public hospitals. And on the percentage of tests coming back positive, his indicators did not account for the fact that for some time the city was encouraging tests for only highly-symptomatic individuals or those who had been exposed to known coronavirus-positive people, then significantly widened the pool as testing capacity ramped up.

Well before Friday, when the mayor announced a shift in how he’d be presenting the metrics that will align him much more with his health department’s website, the city had been showing strong progress on two of the three metrics relative to the thresholds shown by the health department under its “milestones” tab on its widely-used coronavirus data page.

But even as he centered his daily briefings around his three indicators, only to shift them as the city got closer to beginning to “reopen,” de Blasio’s tallies matter less to the city’s future than seven metrics Governor Cuomo released in early May, which de Blasio has only discussed when asked by reporters.

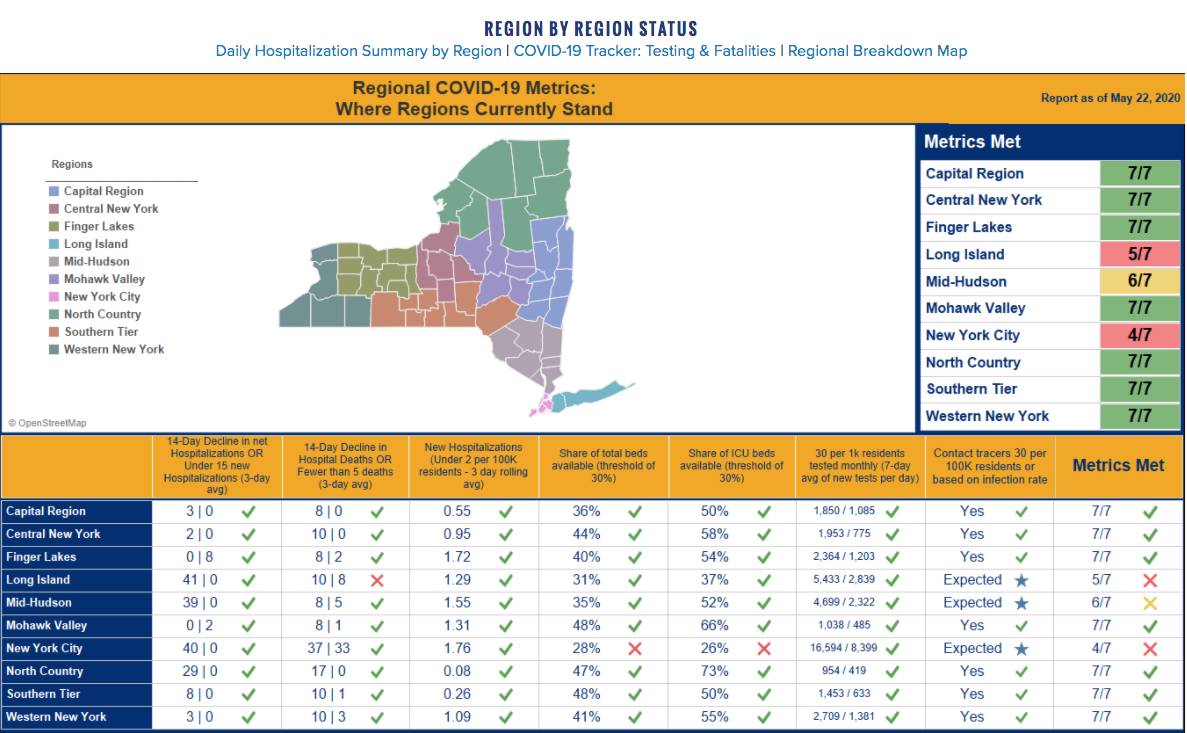

Cuomo’s March 20 “New York on PAUSE” executive order was what placed New Yorkers under a semblance of stay-at-home restrictions and shut down or significantly limited many “non-essential” businesses, starting March 22. On May 4, Cuomo announced the state’s seven metrics that regions would have to meet to begin reopening, a process set to occur in four phases. Seven of 10 regions have already hit the metrics to enter phase one, with two more expected early this coming week, leaving only New York City remaining. The metrics to enter phase one include:

-Consistent decrease in the three-day rolling average of hospitalizations over 14 days, or keep the daily increase in hospitalizations under 15 over a three-day average.

-Consistent decline in daily deaths over 14 days, or keep the daily increase under five deaths over a three-day average.

-Fewer than 2 new hospitalizations per 100,000 residents over a three-day rolling average.

-A minimum of 30% availability of hospital beds.

-A minimum of 30% availability of ICU beds.

-A daily testing capacity of 30 tests per 1,000 residents per month.

-Hiring a minimum 30 contact tracers per 100,000 residents.

The first phase of reopening, as determined by the state, will allow manufacturing, construction, and wholesale and curbside-pickup retail to resume operation.

So far at his daily briefings, the mayor has not addressed each of the state’s metrics individually, even as the city approaches meeting them all. The city has met four metrics – on hospitalizations, deaths, and testing – and is close to meeting the rest. As of Friday, the city hospital bed availability was at 27% and ICU bed availability was at 28%, and it was on track to soon hire the requisite number of contact tracers, who will help execute the testing, tracing, and isolation program deemed necessary to reopening.

The mayor has expressed familiarity with the state’s metrics when asked about them by reporters, and indicated on Friday that he agrees with them and the reopening stages they allow regions to begin. “I think the state standards make a lot of sense,” de Blasio said. “They're careful. They go through stages. You have to prove each stage before you move to the next one.”

On Friday, the mayor announced the city’s shift to “thresholds” for its first phase of reopening, which he said is expected to happen by mid-June. The thresholds are a different way of looking at the mayor’s three indicators, he explained, saying that given the city’s progress it was time to take the longer view.

De Blasio said the daily hospital admissions for suspected COVID-19 will have to remain below 200; the daily number of people in municipal ICUs (now counting non-COVID-19 patients as well) will have to be under 375; and the city will have to stay under 15% of people testing positive for coronavirus each day.

“We want to move forward,” de Blasio said. “We want to get to that first phase of restart....What is clear is, for the first time I've seen these indicators stay consistently low and so it's time to talk about the indicators differently as we prepare for phase one,” the mayor said, apparently unaware that his health department had been showing such progress and thresholds for days. “The day-to-day changes, the small up-and-downs matter less. What matters more now is staying at a low level and keeping that way. And so, we're going to be about thresholds now. So, our indicators that we talked about before were trend lines, now we're going to talk about thresholds and that's going to be the focus going forward.”

On Friday, de Blasio showed that on Wednesday, May 20, there were 76 new hospital admissions of coronavirus patients, 451 patients in ICU, and 11% of positive COVID-19 tests. On Sunday, de Blasio did not hold a briefing but tweeted the latest data on his three metrics, attaching graphs and saying, “Hospital admissions and positive tests for COVID-19 are looking good — and the number of patients in @NYCHealthSystem ICUs continues to drop.” Data for Friday, May 22, showed just 53 new hospital admissions, 415 ICU patients, and a 7% positive test rate.

He continued, “The strategies are working. Social distancing is working. What you’re doing is working, New York City. Keep it up.”

Even between his Friday presentation and his Sunday tweet, de Blasio’s graphs had different labeling: whereas on Friday the three threshold graphs were labeled “indicator threshold,” on Sunday the graphs had the health department language of “we want to be below this line.”

|

|

|

Click to enlarge

Asked to further explain his decision to focus on new metrics, de Blasio told reporters on Friday, “The trend lines were a great measure, because they said to us, we couldn't just, you know, make a little bit of progress. We have to make a lot of progress. We have to keep moving in the right direction...But we then realized in recent days that with two of the three indicators, we are below the threshold we would need to be at on a long-term basis…So, it got to the point of saying, hey, we need to look at our definition and see if it makes sense at this moment. We're going to always, always vary our approach according to new information and new realities. We're all learning together about this. So, it's this simple. The thresholds now make sense. This is a standard.”

De Blasio’s realization had already been apparent to his health department and anyone using its data web-page.

With de Blasio's new "thresholds" and as of the latest city and state numbers, the gaps for the city to hit both de Blasio's and Cuomo's metrics to begin "reopening" boiled down to: 40 fewer people in city's public hospital system ICUs (city metric); 4% more ICU beds available (state metric); 2% more of total hospital beds available (state metric); and hiring requisite contact-tracers (state metric the city is "expected" to meet soon).

But in the bigger picture part of any confusion around metrics and a possible reopening of New York City also stems from different messages being put out by the mayor and the governor, including where de Blasio has focused on his three indicators while Cuomo has presented his seven metrics.

At times during the crisis, the two Democrats seem to have continued their long-running feud, with the governor repeatedly making moves that appear to undermine or show up the mayor, and the mayor taking apparent steps to get ahead of the governor or establish his own authority.

When de Blasio said a stay-at-home order may need to be issued and told New Yorkers to prepare for it, Cuomo repeatedly shot down the idea just days before putting an order in place to effectively achieve the policy the mayor had said should be considered. After the mayor said schools will need to stay closed for the rest of the school year, Cuomo insisted that the mayor did not have the authority to make such a declaration, before declaring it himself a few days later. The two held separate events on the same morning to welcome the USS Comfort hospital ship to Manhattan’s west side.

Even now, the state and city have not come to an agreement on counting the number of deaths from COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. As of May 22, the city reported 16,333 confirmed deaths and 4,753 probable deaths, for a total of 21,086 deaths. The state, on the other hand, reported a total of 15,520 confirmed deaths in New York City as of May 22.

Yet Cuomo and de Blasio have both insisted that there is little to no daylight between the state and city. De Blasio said on Thursday, “The big story here now over three months is that the city and state have been very, very much on the same page. There's been a couple of times where there's been different perspectives. We've worked them through. But overwhelmingly...not only did everyone communicate all the time, but there's overwhelmingly a sense of common purpose, common strategic understanding.”

On May 15, de Blasio even indicated the city and state may work together to further shift the requirements for the city to begin reopening, saying, “Anything we do would be in close coordination with the state. And look, if conditions suddenly became more favorable, we'd have that conversation with the state and obviously we and they could make adjustments. But, right now, I think we're all aligned that the first half of June is the earliest opportunity for even some lessening of restrictions and we'll work together on that.”

At his own daily briefing on Friday, when asked about the different communications from the mayor on reopening, particularly on schools, Cuomo said, “I don't think we're on a different page at all on schools and reopening. My position is I don't have a position. I don't know whether or not they should reopen yet. We're getting more information. We're getting more data. And we'll make the decision on the fall reopening in a timely way. We're telling them, go ahead, do your plans. Tell me how you would take a classroom, reduce the density. Tell me how you would reduce density on a school bus. Tell me how you would reduce density in the cafeteria setting, etc. Give us those plans by July and then we have to make a decision about September. But I don't think there's a difference of opinion or position between the state in the city.”

Secretary to the Governor Melissa DeRosa added that there’s been close coordination with the mayor on key decisions, including on allowing small religious gatherings and on reopening beaches over the Memorial Day weekend with strict social distancing restrictions -- though while state beaches are open to swimming, city beaches are not.

“We speak to the city 17 times a day,” DeRosa said. “We've been in lockstep on everything. The indicators that they laid out initially line up almost identically with our indicators. And, you know, we did the religious ceremonies decision, which is something that they agreed with. On beaches, we wanted to take into account the local situations and that was something that I know Mayor de Blasio supported. And so we've been operating in lockstep with the city.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Ben Max contributed to this story.

Pandemic Reinforces De Blasio's Inaction on School Desegregation Recommendations

Mayor de Blasio during a school visit (photo: Edwin J. Torres/ Mayor's Office)

As the coronavirus pandemic further exposes deep fissures in the city's education landscape for low-income students and students of color, it has also further stalled Mayor Bill de Blasio's already-halting efforts to integrate New York City's deeply segregated schools.

In the nine months since a de Blasio-appointed advisory group released its final recommendations on ways to desegregate and in other ways improve city schools, virtually nothing has been said on the subject out of City Hall or the Department of Education beyond a commitment to review them. The mayor said in early September that he would take “the whole school year for deep stakeholder engagement” on the recommendations, but took no public steps in the subsequent six months. Then the pandemic came to New York. The mayor's office is now acknowledging any review effort continues to be on hold as the government's focus and resources are diverted by the pandemic.

The school year and the first chapter of pandemic-induced remote learning is nearing an end, with major admissions policy decisions imminent. Whatever changes de Blasio may advance, he has left many advocates for school desegregation, including even members of his own advisory group, confused and frustrated by the lack of action before the outbreak hit.

"We have not heard back from the Department of Education about whether or not they are going to move forward on any of our recommendations," said Maya Wiley, co-chair of SDAG and former counsel to de Blasio in the mayor’s office, in an interview with Gotham Gazette. "Our position as a group was that we obviously wanted to hear back and hoped for some response on some of the recommendations. We didn't necessarily believe they all would require a full year."

"Yes, it would be better if we had made more progress on the SDAG recs before the pandemic," said City Council Member Brad Lander, a Brooklyn Democrat who has pushed for integration-focused admissions reforms in schools within his district and across the city. "That said, the crisis presents a challenge, which we need to rise to and which creates an opportunity to be more thoughtful about school admissions."

With learning, assessment methods, and application processes all disrupted, de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza have indicated the city will soon offer changes to school admissions processes, raising hopes and fears of the potential opportunity to expedite reform, though it is unclear how ambitious they may be.

"Many things are going to be reevaluated as a result of this crisis,” the mayor said at a press briefing on May 7 when asked about possible changes to school admissions processes, which must move ahead in some form soon. “The whole concept I've been putting forward, that we are not just going to bring New York City back with the status quo that was there before, but we're going to try and make a series of changes that favor equity and fairness. We were already in the process of doing that when it came to school admissions. So, certainly, the screened schools are being reevaluated and we’ll have more to say on that in the future.”

De Blasio did not mention the recommendations put forth in August of last year by his School Diversity Advisory Group (SDAG), a controversial and sweeping set of proposals that he has largely avoided since their release.

"When this pandemic started, we shifted our focus to the success of remote learning and the wellbeing of students and staff,” wrote mayoral spokesperson Jane Meyer by email, in response to questions about the status of the administration's review of the School Diversity Advisory Group’s recommendations. “Our priority right now is the health of New Yorkers and academic success of our students in these extraordinary times, and we’ll continue to adjust policies to meet those goals for the duration of this crisis."

When the group published its final report in August, de Blasio said he would assess the recommendations over the next year. “Now we’re going to really dig deep into what makes sense and by the end of the school year we’ll know where we’re going,” he told reporters a few days after the recommendations were released and as the new school year was starting, citing plans to undertake more community engagement. At the time, de Blasio was in the midst of his four-month campaign for the Democratic nomination for president.

"We are taking a very, very deep dive into what the recommendations have been from the School Diversity Advisory committee," Carranza said at the time.

But the mayor has discussed little publicly since then and the recommendations -- or anything related to school desegregation -- were conspicuously absent from his State of the City address in February, when he outlined his priorities for the year, his next-to-last as mayor, under the theme of “Save Our City.”

De Blasio’s further delay in addressing school segregation in New York City, to the extent that it may be attributed to the pandemic fallout, is another example where the coronavirus crisis not only exacerbates racial inequalities by hitting communities of color harder but also by diminishing the government's overall capacity. But the situation also speaks to the slow pace at which the de Blasio administration has approached a particularly thorny issue that goes to the heart of the mayor's promises to end “the tale of two cities” and create "the fairest big city in America."

New York has among the most segregated schools of any state in the country, with a heavy concentration in New York City. A groundbreaking UCLA study in 2014 found that 19 out of New York City's 32 school districts had 10 percent or less white students, including all of the Bronx and two-thirds of Brooklyn. It showed a correlation between racial segregation in schools and concentrations of poverty.

In 2017, after years of pressure from advocates and elected officials, the mayor announced the "Equity and Excellence for All" plan to improve all schools, especially those predominantly serving students of color and historically lacking investment. Soon after, he empaneled the School Diversity Advisory Group to explore ways to increase “diversity” in city schools, while he studiously avoided the words “segregation” and “integration.”

"We have to improve the quality levels of our public schools and we have to do it in a way that promotes equity – that’s the mission, now – that’s the central mission," he told reporters on June 9, 2017, a few days after the announcing the plan. When pressed on the specific issue of segregation he said: "The quality of education for students is paramount in this discussion. So, when we talk about it, we have to understand, we need any plan to start with the quality of education for all students, including those who have not gotten a fair shake previously."

The group, made up of students, parents, and experts, released two sets of recommendations, one in February 2019, which was largely adopted by the mayor and chancellor, and a second in August, which contained significantly more controversial changes to admissions, districting, and tracking policies.

"Our hope was that it would spur a lot more innovation and creativity, not just out of the Department of Education at the administrative level, but also within school districts and across school districts," Wiley said in the interview.

The recommendations are based on the concept that "more educational opportunity was not a one size fits all," she said, and "a clear roadmap around the kinds of admissions policies that were clearly creating more problems than solutions.”

The final recommendations included a range of small and large proposed solutions to the problems of school segregation and its many negative consequences, the most controversial among them being to limit middle school admissions screening and phasing out "gifted and talented" programs, both shown to favor white and Asian students, and the group recommends replacing G&T tracts with more inclusive schoolwide enrichment models. Another controversial point, redrawing school district lines, gets at the geographic element involved in school segregation, especially for elementary schools.

The proposal received fierce opposition from some parents who have had the means to prioritize stronger school districts when deciding where to live and for years have found a sympathetic ear in the mayor, as well as a number of local elected officials.

Wiley said the big ticket items have come to overshadow simpler, perhaps less-controversial ones.

"Some of these are really obvious and easy to fix," she said. "For example, if you use attendance as an admissions factor, you are going to essentially make it more difficult for low-income students of color to be competitive."

Another issue is disciplinary history. "A student who may have had a disciplinary issue because they spit gum on the floor. Does that mean they don't deserve real consideration and opportunity to get into a good program in middle school or in high school?" she asked. "We conflate a lot of different kinds of disciplinary issues and also the ways it sometimes works against low-income students of color in particular."

According to SDAG's first report in February, 87 percent of New York City public school suspensions are of black and Latino students, despite making up 66 percent of the student population.

Fed up with the administration's silence on desegregation, student-led groups IntegrateNYC and Teens Take Charge, which had been prominent advocates in the lead-up to the mayor announcing the SDAG, organized a school boycott to push de Blasio and Carranza to integrate city schools, including by eliminating admissions screens. The boycott was planned for May 18 to coincide with the 66th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision but was called off because of the pandemic. The groups and their allies have continued to use social media and other avenues to keep the conversation alive.

As the end of the school year approaches and students and parents look ahead to the fall, some advocates and local elected officials have called on the city to embrace innovative redistricting and admissions models that have been piloted in certain districts. The most prominent one is in Brooklyn’s Community School District 15, where in 2018 middle schools eliminated screening and moved to a ranked-choice lottery system with a 52 percent of seats reserved for low-income students, students in temporary housing, and English-language learners. Enrollment data released last November after the first year showed promising results for integration.

"Next fall, as today’s fourth graders and seventh graders start the process of applying to middle and high schools, the Department of Education will need to make significant changes, since so many of these decisions have relied on grades, attendance, and test scores," wrote Lander, who represents parts of Community School District 15 and championed the new system, in a new letter to Carranza. "The admissions changes we made together for middle schools in District 15 last year can serve as a model for how to address middle school admissions for the 2021-22 school year."

But Lander argues an emergency pandemic response should not be an invitation to replace thoughtful policymaking. "I don't think this moment is a good moment to make permanent long-term decisions. There is just too much uncertainty, too little opportunity to do good, inclusive public process," he told Gotham Gazette in an interview.

"In terms of where the city is in regards to integration, not enough system-wide action has been taken,” wrote Matt Gonzales, director of the Integration and Innovation Initiative at NYU and at one point a member of the SDAG, by email. “The lack of action on the SDAG recommendations is definitely an indication of this."

"However, if you look at the history of integration efforts in NYC, it is also true that no administration has moved the needle more than the current one. The number of districts and individual schools who've implemented plans has increased," he said.

"We very much applauded the fact that the Department of Education, along with the state, were funding districts to look at how they might integrate their schools," said Wiley. "We thought there should be more of that, so that there was actually support for that kind of innovation."

"The good news is the Department of Education was doing some of that already. We hoped they would do more. Obviously it's a challenging time now," she said.

Gonzales said the pandemic has slowed community planning efforts underway in Community School Districts 13, 16, 28, and 9, "but I am hopeful those resume when society resumes."

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette

De Blasio Hasn't Visited Rikers Island During His Second Term

Mayor de Blasio on Rikers Island (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

In his second term in office, Mayor Bill de Blasio has worked with the New York City Council to usher through a plan that will close the scandal-ridden Rikers Island jail complex and replace it with four borough-based facilities by 2026. He has repeatedly decried the crumbling infrastructure and the well-documented incidents of violence, by detainees and guards, among the many issues of the sprawling Island facilities. But the mayor has not visited Rikers Island in three years, and not at all since he was reelected nor since the deadly coronavirus pandemic took hold in the city.

The mayor’s last visit to Rikers was in June 2017, a few months before he won his second and final term. Three months prior to that visit, he had announced his support for the plan to close Rikers that had been proposed by the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, convened by former City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and chaired by former New York Chief Judge Jonathan Lippmann.

The mayor hasn’t always taken a keen interest in the issues that plague Rikers. His first visit to the island was in December 2014, nearly a year into his first term, in the aftermath of federal and state investigations into the conditions of the jails. De Blasio said then and has said repeatedly since that the conditions in Rikers jails were something he did not have a firm grasp of before becoming mayor.

He also initially hesitated to back calls from various advocates and elected officials, including Comptroller Scott Stringer and Mark-Viverito, then the Lippman Commission’s plan, before adopting the essence of that plan and seeing its initial phases through.

The focus on Rikers has only intensified in his second term, however, as the borough-based jails plan sped through the city’s land use review process, finalized by the City Council. The city combined all four jail facilities, located in each borough save Staten Island, into one land use application, shortening the window for its approval. The overall plan faced criticism from some criminal justice reformers, while each individual facility proposal was the target of community opposition. Concessions were made to local Council members, with the sizes of the new facilities reduced, and the plan was approved.

The coronavirus pandemic has also renewed attention on Rikers, as city jails have seen clusters of infections, and the deaths of three detainees and ten corrections employees. When the city was beginning to shut down in March, the mayor suspended in-person visits to all jails to limit the spread of the virus. He’s also ordered the release of hundreds of detainees who were being held on nonviolent offenses or were vulnerable during the outbreak because of their age or health.

Several news reports have emerged since then of the apparent mismanagement of the crisis by the Department of Correction. The New York Times, in a Wednesday report, quoted several unnamed Rikers corrections officers who complained that they felt at risk because of the failure to respond adequately to the outbreak. But none of it has prompted the mayor to head to the Island to see the issues for himself. In contrast, de Blasio has been visiting food distribution centers, traditional and pop-up hospital facilities, supply warehouses, and other sites.

The mayor’s press secretary did not provide comment when asked about de Blasio’s last trip to Rikers and whether he felt it may be necessary to see the conditions there in person during the pandemic.

Other elected officials have similarly not been to Rikers in recent months, citing the concern for the safety of detainees and DOC employees. Notably, elected officials haven’t shown the same reluctance to visit hospitals where tens of thousands of New Yorkers infected with the virus have been admitted.

In early October, just prior to the Council’s vote to approve the borough-based jails plan, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and several of his colleagues paid their most recent visit to the Island.

Johnson said in a statement that the Council is continuing its oversight of the situation on Rikers. “From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I urged for the release of as many incarcerated New Yorkers as possible to tackle the spread of this virus in our jail system,” he said, adding in particular that individuals should not be jailed for technical parole violations.

“We had a more than seven-hour long hearing on Tuesday to assess how DOC is handling the crisis. As we mourn the death of DOC staffers and incarcerated individuals, we are in constant communication with the Department, the Board of Correction, and advocates to ensure robust oversight as this situation develops,” he said.

A spokesperson told Gotham Gazette that Johnson does not have plans to visit the island any time soon, and that only essential workers should be travelling to and fro.

Council Member Keith Powers, who chairs the Criminal Justice Committee which has Rikers under its purview, said he has thought about visiting Rikers but has balanced that with the need to ensure that there is no further spread of the virus. “I thought about going in at some point to see conditions for myself, but I did think it was right to withhold doing that for the time being based on what's going on in the world,” he said.

Powers was among the members who went to Rikers in October. He said he has been in constant contact with the Board of Corrections and DOC to conduct ongoing monitoring from afar. He said he is concerned about reports he has received from the Board of Corrections that some social distancing protocols are not being followed, and the concerns being raised by advocates that the conditions at Rikers are ripe to make the crisis worse. “My philosophy here is we can always be doing more and doing better to help people out as they are in our city jails,” he said.

He also emphasized that he wouldn’t want to make a symbolic trip to Rikers. “I would do it for substantive reasons to make sure that there is an appropriate response to the Covid crisis within our city jails and to oversee how the operations are running during the public health crisis,” he said.

He added, “This crisis only reiterates to me that you can't move vulnerable populations out of sight and out of mind. Because when they are visually out of sight, out of mind, they are from a policy standpoint or from a budgetary standpoint, out of mind for many folks here as well.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette