Times Square: 100 Years of Pleasure and Dissipation

|

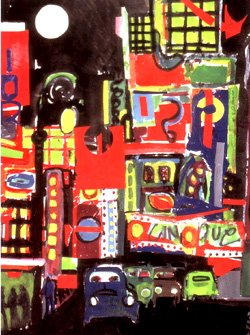

Romare Bearden, Midtown, on exhibit at the Whitney. It Happened In 1904 |

Not long ago I visited Vienna. As soon as I arrived, I walked to the plaza at the center of town, the Stephansplatz, dominated by the dark mass of St. Stephen’s Cathedral. I was standing, or so I imagined, in the historical center of Europe – at least the Europe of 1900. It was very quiet. The Stephansplatz -- like the Place des Vosges or the Piazza della Republica or Belgrave Square -- is a serene place set aside for pedestrians, for all the great European capitals were fully formed long before the advent of the automobile. Standing there, I couldn’t help thinking of another square, which a melancholy bard named Benjamin De Casseres once described as a “ganglion of streets that fuse into a traffic cop.” I was thinking, of course, of Times Square, the crossroads of New York – of the planet, in its own estimation.

There may be some great popular tunes about the Stephansplatz but, somehow, I doubt it. The whole world knows Times Square, and not only through songs but through shows and movies and electric signs and radio and TV. And while other mythic urban places have about them the solemn grandeur that comes of tragedy and bloodshed, Times Square is a place associated only with pleasure and dissipation, even if at times the dissipation has had an ominous edge. Since 1904, when the subway opened up, when the Times Tower was completed, and when Mayor George McClellan officially gave the neighborhood its name – Times Square has been the world’s preeminent good time place.

We can trace Times Square’s destiny back to 1811, when a commission appointed by New York’s Common Council published an astonishingly audacious plan to tame the rocky wilds on Manhattan into a grid of streets. The commissioners noted that they had considered the use of “circles, ovals and stars” but had concluded that since “a city is to be composed principally of the habitations of men, and that straight-sided right-angled homes are the most cheap to build,” New York would have no such embellishments. The only exception to the city’s unvarying rectilinearity would be the diagonal stretch of Broadway, too prominent a thoroughfare to be erased.

From the beginning, New York’s entertainment district had tended to cluster around Broadway simply because the street was broad and ran more or less up the middle of the island. The city developed northward, and the development of new residential and retail neighborhoods tends to push the theaters, bars and restaurants farther up Broadway. By the 1860s, the city’s first theater district came into being at Union Square, where Broadway crossed 14th Street and a large waste area had been turned into a park. The juncture of Broadway and 14th Street came to be known as the Rialto because show people passed through it all day and night.

The Rialto kept moving northward. By the 1880s, the entertainment district had reached the junction where Broadway crossed 23rd Street at the base of Madison Avenue. The area immediately around Madison Square, a lovely park, was New York’s most refined shopping district. The lowlife beckoned from Sixth Avenue, where the elevated railroad carried New Yorkers of lesser ilk; bars and brothels, clustered along the side streets. But the worlds appear to have mingled relatively little.

The theaters moved up to where Broadway crossed Sixth Avenue, known as Herald Square, and continued onward; by 1893, Oscar Hammerstein, a cigar magnate, had built a great ocean liner of a theater in the prodigious gloom of 44th Street, just beyond the point where Broadway crossed Seventh Avenue.

|

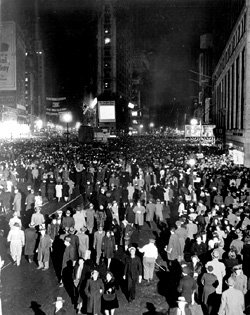

View of a crowd gathered at Times Square in 1944. |

In all likelihood, the process would have gone on repeating itself but for one colossal event: the building of the subway. Suddenly, Times Square was a point of convergence not only for surface transit but for the most efficient means of mass transit ever invented. And as a vast network of bridges and tunnels were completed over the course of the next decade, Times Square became a switching point for every form of transportation. All this happened in the midst of an immigration boom. The intersection of 42nd Street and Broadway was already considered the most congested crossroads in the world by the early years of the new century.

Times Square was the pool into which this vast new life emptied. The rich man went to the “lobster palaces” and the arch revues staged in the roof gardens, while the poor man paid a quarter to hear an immigrant like himself belting out a ballad in a vaudeville show.

At a time when new institutions like the department store and the office building were throwing men and women, rich and poor together as never before, Times Square was the ultimate leveler. And as we know from students of culture like Lewis Erenberg and Ann Douglas, this mixing and leveling gave a democratic, hybridized charge to music and dance and theater; the jeunesse doree of Fifth Avenue swung their hips and shoulders to ragtime dances that had bubbled up out of black culture.

And traffic. Times Square was not a “square,” a place carved out of the urban fabric, but the fabric itself, a gorge that traffic squeezed through in a great rush before disappearing out the other side. It was the city into its pure state, nature having been obliterated down to the last blade of grass. The Times Square character lived and died inside an asphalt triangle. Times Square gave birth to a race of men – and some women – for whom nature, and “naturalness,” was a con, and the only real life was the one made by men in buildings.

Times Square came increasingly to feel like a village, intricate and inbred, furnished with a complete set of folkways, mannerisms and habits of speech. We miss it now, of course – not the characters themselves but the sense of mythological possibility. Bulldozers chased the ghosts out of Times Square; or rather pornographers and drug dealers and loony street people chased them out first, and then the bulldozers cleaned up the mess.

|

The New Amsterdam Theater |

In its heyday, Times Square somehow managed to feel hermetically enclosed even while it was the busiest and most famous crossroads in the world. That’s all over: The tall buildings that line Broadway look a lot like the tall buildings that line Third Avenue and have much the same corporate tenants. The retail stores on 42nd Street have brothers and sisters all over the world. Even the street vendors ply their trade in Miami or Rio in the off season.

But whenever I despair, I remind myself that Times Square has had many incarnations over the last century; this one doesn’t have to be the last. Perhaps when the new paint starts to chip, even this Times Square will gain some power over our imagination.

James Traub is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and author of “The Devil’s Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square.”

This article is excerpted from the spring 2004 issue of “The New-York Journal of American History, “ the semiannual publication of the New-York Historical Society.

Looking Back at 100

This week, some subway passengers will have the eerie experience of entering their regular train to see that its exterior is no longer stainless steel, but wood; the plastic seats have been replaced by wicker; and instead of those computer-generated red-dots that announce each destination, there will be old-fashioned incandescent light bulbs hanging from the ceiling.

These are not the run-down trains that gained for the New York Subway system the designation as “The Most Awful Ride in the World” way back in 1938. They are even older than that; so old that transit officials are calling them “vintage trains" now. Some of them were built as early as 1904, the year the subway began.

The surprise rides in these old subway cars, which will be placed at random throughout the city, are meant to celebrate a special anniversary. On October 27th, the New York subway system turns 100. For weeks now, people haven’t just been riding the subways; they’ve been watching films about it, and listening to lectures, taking guided tours, and attending museum exhibitions.

The subway centennial is one of an unusual number of anniversaries being given elaborate commemorations in New York this year, many of them centennials -- among the most notable besides the subway, Times Square and the fire on the steamboat General Slocum that killed more than a thousand people; among the least notable, the centennial of the Friar’s Club.

What was it about 1904, which also saw the birth of Cary Grant, Graham Greene and Campbell’s Pork and Beans -- and, some claim, the invention of the ice cream cone and of the hamburgeras well?

In New York alone, where immigrants swelled the population and the city exploded with social movements, new businesses and new technology, the year saw the birth of the first public high school for the sciences, Stuyvesant High School and the Explorers Club to promote both science and adventure ; the Afro-American Realty Company to develop property in Harlem and encourage black people to move there; and the Hispanic Society of America, whose museum in upper Manhattan celebrates Spanish culture. (There are special events commemorating all of these centennials except the realty company.)

But if a lot happened in 1904, that is not the sole reason why there are so many centennial commemorations this year.

Curators and historians certainly like these events. “If you’re going to get news organizations to pay any attention at all to history, you have to give them a news peg” and anniversaries provide that, said Kathleen Hulser, public historian at the New York-Historical Society, which is itself celebrating its own bicentennial, as well as marking the bicentennial of the death of Alexander Hamilton.

Anniversary observations, observes Sarah Henry, deputy director of the Museum of the City of New York, “give you a very interesting opportunity to look at where we were then and where we’ve come to.”

But it is not just the professionals who are looking back at New York City history; the general public seems interested as well. Attendance at museums and historical sites has increased.

“I would venture to say that after 9/11, the New York City community was brought together not only by a shared tragedy and desire to rebuild our city and our lives, but also by a palpable sense that we were living in a historic time," said Valerie Paley, editor of the New-York Journal of American History, which put out an issue on anniversaries. "Perhaps it is the need to take a look at the past, to put the present in perspective, that is driving that impulse to recognize the city's history in a different way.”

This is certainly not the first time that New Yorkers have suddenly become intensely interested in their history. It has happened, some suggest, at least twice before -- ironically, exactly 200 years ago, when the New-York Historical Society was formed...and 100 years ago. The oldest existing house in Manhattan, the Morris-Jumel Mansion, which was built in 1765 and had served as George Washington's headquarters during the American Revolution, was turned into a museum in 1904. "The museum was created at the height of the colonial revival movement," reads a brochure celebrating the mansion's centennial as a museum, "a time when the romanticization of American history was prevalent and Revolutionary figures were viewed as idols."

THREE CENTENNIALS

General Slocum Fire

Until September 11, the General Slocumfire was the deadliest disaster in New York City history. It killed at least 1,021 people who had set out for a pleasure cruise up the East River.

“If you had ancestors who were in New York City in June 1904, quite possibly they had some role, however minor, in the Slocum disaster" -- knowing a victim, contributing to a relief fund, helping to treat the victims, said Ken Lieb, who has organized events to commemorate the tragedy. "The same thing happens with 9/11 . . . the gamut of people involved,” he said.

For decades, as Edward O’Donnell has written (see related article), the June 12 disaster was largely forgotten. But recently, Lieb said, interest in the tragedy had increased, partly because of the 100th anniversary.

Most of this year’s remembrances, though, are of triumph, not tragedy. “People prefer to remember happy things, so you celebrate victories, not losses,” Hulser said.

The Subway

Whatever irate straphangers may think, the celebration of the subway marks a triumph. One hundred years ago on October 27, the first subway left City Hall. The trip so thrilled then-Mayor George McClellan that he drove the train himself, refusing to relinquish the controls to the motorman.

But the subway represents more than a technical achievement, said Peter Derrick, author of “Tunneling to the Future,” who will discuss his book in a Gotham Gazette book chat on the subway's birthday, October 27. The train enabled people to move out of densely packed neighborhoods. “All the anecdotal evidence we have is that they were able to have much better lives,” Derrick said. “It’s the only time people were able to move up the ladder without making more money.” (See related article)

Some hope the subway anniversary can spur a better transit system for the future. (See related articled by Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign). Mike Wallace, director of the Gotham Center for New York City History, which will hold a forum on the subway on November 10, said ideally such events should examine important issues. Noting that cars came along at the same time the subway did, he would hope to see someone look at “rail versus road … an assessment of the worthiness, expense and ecology of these two systems, which have been struggling for the city’s soul.”

Times Square

This year’s third major centennial marks the year that the city gave a new name to an old square, at the behest of the publisher of the New York Times, who wanted to match the rival New York Herald’s square eight blocks south. The Times moved its headquarters to the area a year later.

Times Square gained ground as the city’s entertainment district in 1904 because of the subway, as James Traub explains. (See articleby Traub) With the shady characters and tawdry businesses now pushed out by chain stores and franchise food, writers and critics have used the anniversary to ponder the Times Square of today.

THE PAST IN THE PRESENT

The New-York Historical Society, celebrating its 200th birthday, had been planning an exhibition to coincide with the hundredth birthday of Times Square. It canceled that exhibition, though, and focused on a five-million-dollar blockbuster, an exhibition on Alexander Hamilton, the Revolutionary war hero, first Secretary of the Treasury, the founder of the "New-York Evening Post" and the man now on the ten-dollar bill (a huge blow-up of which is draped across the society's building), who died in a duel with Aaron Burr the same year the historical society was founded.

Some historians were publicly aghast, accusing the New York museum of forsaking New York and going national. Some even looked at the funders -- new board members Richard Gilder and Lewis Lehrman, both conservative businessmen (Lehrman was the Republican candidate for governor in 1982), --- and the curator -- a Hamilton biographer and a long-time editor at the conservative National Review -- and wondered if there was...if not a vast right-wing conspiracy... at least a political agenda.

Whatever the merits of the accusation, it would certainly not be the first time that the past has been used to weigh in on the present. Indeed, it is the major argument for studying history. The exhibition does call Hamilton the most modern Founding Father, indeed, "the man who made Modern America," and the largest gallery of the exhibition includes huge screens that alternate quotes from Hamilton with filmed vignettes of modern American life.

“The reason al-Qaida and its helpers and patrons struck the World Trade Center was that the towers symbolized modern America -- Hamilton’s America,” the curator, Richard Brookheiser wrote in City Journal.

THE PAST IN THE FUTURE

Will any of the events commemorated this year engage the imagination of the public of 2104? Is something happening right now that will merit a centennial celebration in 100 years?

In a city famous for bulldozing its past, it should come as little surprise that one of the biggest celebrations of the nineteenth century commemorated Evacuation Day, the day that the British troops left New York City, their last outpost in the former colonies. In 1883, speeches, parades and banquets hailed the 100th anniversary of Evacuation Day. One hundred years later, however, in 1983, New Yorkers were focused on the centennial of the Brooklyn Bridge; Evacuation Day had been forgotten.

• • • • • • • • • •

Centennial Calendar

ALEXANDER HAMILTON BICENTENNIAL

Alexander Hamilton: The Man Who Made America Modern

This exhibition explores the life and impact of Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804).

New York Historical Society

Through February 28, 2005

"Alexander Hamilton: In Worlds Unknown"

An original multimedia play.

New-York Historical Society

Showing though February 2005

The Age of Alexander Hamilton

A lecture series on Hamilton including his role in the U.S. financial revolution, Hamilton and the Constitution, and why he was never elected president.

SUBWAY CENTENNIAL

Several exhibitions at the New York Transit Museum commemorate the 100th birthday of the opening of the subway:

--"The City Beneath Us: Building the New York Subway" includes photographs of subway construction. (Through spring 2005)

--"Centennial Celebration" commemorates the 1904 opening of subway with artifacts, maps, and drawings. (Through spring 2005)

--"'The World's Safest Railroad': How Ivy Lee Promoted New York's Subway System, 1916-1932” in the museum's Grand Central Station annex, features ads and publications for the subway system. (Through October 31)

--“Subway Style” 100 Years of Architecture and Design in the New York City Subway, in Grand Central Station, displays artifacts to examine the aesthetic side of the transit system. (Through November 5)

"The Riders and the Rebirth of City Transit"

An exhibition on how activism has improved mass transit.

Municipal Art Society

Through October 30

“Around Town Underground”

Subway related art by some of New York's finest printmakers.

New-York Historical Society

Through November 7

“Three on the Subway”

Photographs of the subway over the past 30 years by Bruce Davidson, Camilo Jose Vergara, and Sam Hollenshead.

Museum of the City of New York

Through January 17

“Tunnel Visions: Subway Photos, 1904-1908”

Photographs documenting the construction of the underground lines from 1904 to 1908.

New-York Historical Society

Through February 20, 2005

“100 Years of the New York Subway: A Look Back and A Look to the Future”

This forum will put the subway in historical perspective, bring the story of the subway up to date and take a look at what might happen to it in the future.

CUNY Graduate Center

November 10

(For a more complete listing of subway events, go to http://www.mta.nyc.ny.us/nyct/cen/events.htm)

NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY CENTENNIAL

“ Impressions of New York”

Prints from the society’s collection depicting New York City, from 1626 to 1995.

New-York Historical Society

Through March 6, 2005

HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA CENTENNIAL

Hispanic Society

The museum of Spanish art, history and culture is commemorating its centennial with special events.

“Capella de Ministrers-ludici Signum”

A concert of Renaissance music

October 26, 6:00p.m.

Convergence and Diversity: Art of the Hispanic World

A series of gallery talks to highlight artworks from the museum’s collection.

Three Years of Rebuilding

The day after his speech at the Republican National Convention, which was largely about the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani was questioned by a group of delegates from Iowa, who asked whether New Yorkers have been able to recover from 9/11 as quickly as the rest of the nation.

New Yorkers, being closer to the events, are supposed to be more emotional about the attack, Giuliani reportedly replied, and people outside the city are supposed to feel it less. "But," Giuliani said, "I've found in traveling that it's maybe just the opposite."

And indeed, the delegates who streamed to Ground Zero described wrenching visits to the place where their country was attacked. New Yorkers, on the other hand, had a more complicated set of reactions. Some looked at all the attention given to 9/11 at the convention (Giuliani's speech was only one of several to focus on it), and expressed outrage at what they saw as the exploitation of their city's tragedy for partisan advantage.

Others simply are in a different place than the out-of-towners who have not had to live close by for the past three years. "People who weren't here, it's a big deal in a different way to them than for people who were here on that day," said Maryhope Howland, who was evacuated from her apartment in lower Manhattan on September 11, 2001. While she, along with many New Yorkers, marked with great solemnity the first anniversary of the attack, she did little to mark the date one year later. She will be spending September 11, 2004 celebrating a friend's wedding. "It's not like 9/11 occurs to me every day, " she said. "But it has changed everything."

The emotional reaction is not all that separates New Yorkers from other Americans. The convention focused 9/11 on issues of national defense. Certainly, with New York remaining the most likely target for terrorism within the United States, New York officials and residents understand strident arguments for tight security. At the same time, though, as the city with the largest and most diverse immigrant population, many of whom have suffered as a result of harsh security measures, the importance of civil liberties also hits close to home. And, as a famously liberal city, many New Yorkers are at the forefront of the protest movement against the war in Iraq.

To the nation at large, 9/11 evoked a response that seems largely concerned with protecting and preventing. New Yorkers since 9/11 have focused on rebuilding, and security is only one issue in the rebuilding effort. A half dozen questions have faced New Yorkers over the past three years, questions that have yet to be fully answered:

- Ground Zero

What will Ground Zero look like when it is completely built up?

The major architectural elements for Ground Zero have been designed, but funding issues threaten the redevelopment, which is not scheduled to be completed until 2015. - Transportation

How did the attack transform transportation to and around lower Manhattan?

Public transportation to lower Manhattan has been repaired, and major plans to improve it are underway, though debate continues over additional projects. - Economic Impact

Has New York's economy really recovered from 9/11?

The city has pulled out of a two-and-a-half year recession, but full recovery is uncertain. - Federal Aid

Will the enormous federal aid package ever reach the city?

Over half of the $20 billion pledged to New York has arrived, but the city will not receive the entire amount promised to it for at least five years, if at all. - Security

Is New York, and the country as a whole, capable of preventing and responding to future terrorist attacks?

Facing criticism of its capabilities and a shortfall in funding, the city continues to prepare itself to prevent and respond to future terrorist attacks. - Health and Environment

What are the long-term environmental and health effects that will come as the result of the collapse of the Twin Towers?

Scientists dispute what will happen in the future, while it has become clear that the Environmental Protection Agency performed badly in the days after the attacks.

Next Page: Ground Zero