|

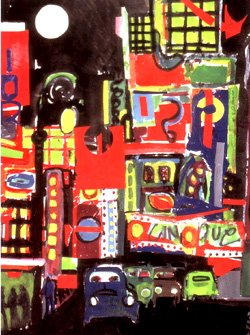

Romare Bearden, Midtown, on exhibit at the Whitney. It Happened In 1904 |

Not long ago I visited Vienna. As soon as I arrived, I walked to the plaza at the center of town, the Stephansplatz, dominated by the dark mass of St. Stephen’s Cathedral. I was standing, or so I imagined, in the historical center of Europe – at least the Europe of 1900. It was very quiet. The Stephansplatz -- like the Place des Vosges or the Piazza della Republica or Belgrave Square -- is a serene place set aside for pedestrians, for all the great European capitals were fully formed long before the advent of the automobile. Standing there, I couldn’t help thinking of another square, which a melancholy bard named Benjamin De Casseres once described as a “ganglion of streets that fuse into a traffic cop.” I was thinking, of course, of Times Square, the crossroads of New York – of the planet, in its own estimation.

There may be some great popular tunes about the Stephansplatz but, somehow, I doubt it. The whole world knows Times Square, and not only through songs but through shows and movies and electric signs and radio and TV. And while other mythic urban places have about them the solemn grandeur that comes of tragedy and bloodshed, Times Square is a place associated only with pleasure and dissipation, even if at times the dissipation has had an ominous edge. Since 1904, when the subway opened up, when the Times Tower was completed, and when Mayor George McClellan officially gave the neighborhood its name – Times Square has been the world’s preeminent good time place.

We can trace Times Square’s destiny back to 1811, when a commission appointed by New York’s Common Council published an astonishingly audacious plan to tame the rocky wilds on Manhattan into a grid of streets. The commissioners noted that they had considered the use of “circles, ovals and stars” but had concluded that since “a city is to be composed principally of the habitations of men, and that straight-sided right-angled homes are the most cheap to build,” New York would have no such embellishments. The only exception to the city’s unvarying rectilinearity would be the diagonal stretch of Broadway, too prominent a thoroughfare to be erased.

From the beginning, New York’s entertainment district had tended to cluster around Broadway simply because the street was broad and ran more or less up the middle of the island. The city developed northward, and the development of new residential and retail neighborhoods tends to push the theaters, bars and restaurants farther up Broadway. By the 1860s, the city’s first theater district came into being at Union Square, where Broadway crossed 14th Street and a large waste area had been turned into a park. The juncture of Broadway and 14th Street came to be known as the Rialto because show people passed through it all day and night.

The Rialto kept moving northward. By the 1880s, the entertainment district had reached the junction where Broadway crossed 23rd Street at the base of Madison Avenue. The area immediately around Madison Square, a lovely park, was New York’s most refined shopping district. The lowlife beckoned from Sixth Avenue, where the elevated railroad carried New Yorkers of lesser ilk; bars and brothels, clustered along the side streets. But the worlds appear to have mingled relatively little.

The theaters moved up to where Broadway crossed Sixth Avenue, known as Herald Square, and continued onward; by 1893, Oscar Hammerstein, a cigar magnate, had built a great ocean liner of a theater in the prodigious gloom of 44th Street, just beyond the point where Broadway crossed Seventh Avenue.

|

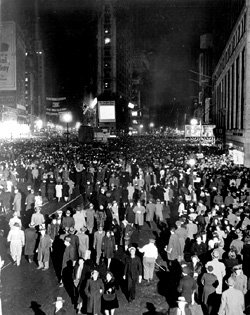

View of a crowd gathered at Times Square in 1944. |

In all likelihood, the process would have gone on repeating itself but for one colossal event: the building of the subway. Suddenly, Times Square was a point of convergence not only for surface transit but for the most efficient means of mass transit ever invented. And as a vast network of bridges and tunnels were completed over the course of the next decade, Times Square became a switching point for every form of transportation. All this happened in the midst of an immigration boom. The intersection of 42nd Street and Broadway was already considered the most congested crossroads in the world by the early years of the new century.

Times Square was the pool into which this vast new life emptied. The rich man went to the “lobster palaces” and the arch revues staged in the roof gardens, while the poor man paid a quarter to hear an immigrant like himself belting out a ballad in a vaudeville show.

At a time when new institutions like the department store and the office building were throwing men and women, rich and poor together as never before, Times Square was the ultimate leveler. And as we know from students of culture like Lewis Erenberg and Ann Douglas, this mixing and leveling gave a democratic, hybridized charge to music and dance and theater; the jeunesse doree of Fifth Avenue swung their hips and shoulders to ragtime dances that had bubbled up out of black culture.

And traffic. Times Square was not a “square,” a place carved out of the urban fabric, but the fabric itself, a gorge that traffic squeezed through in a great rush before disappearing out the other side. It was the city into its pure state, nature having been obliterated down to the last blade of grass. The Times Square character lived and died inside an asphalt triangle. Times Square gave birth to a race of men – and some women – for whom nature, and “naturalness,” was a con, and the only real life was the one made by men in buildings.

Times Square came increasingly to feel like a village, intricate and inbred, furnished with a complete set of folkways, mannerisms and habits of speech. We miss it now, of course – not the characters themselves but the sense of mythological possibility. Bulldozers chased the ghosts out of Times Square; or rather pornographers and drug dealers and loony street people chased them out first, and then the bulldozers cleaned up the mess.

|

The New Amsterdam Theater |

In its heyday, Times Square somehow managed to feel hermetically enclosed even while it was the busiest and most famous crossroads in the world. That’s all over: The tall buildings that line Broadway look a lot like the tall buildings that line Third Avenue and have much the same corporate tenants. The retail stores on 42nd Street have brothers and sisters all over the world. Even the street vendors ply their trade in Miami or Rio in the off season.

But whenever I despair, I remind myself that Times Square has had many incarnations over the last century; this one doesn’t have to be the last. Perhaps when the new paint starts to chip, even this Times Square will gain some power over our imagination.

James Traub is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and author of “The Devil’s Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square.”

This article is excerpted from the spring 2004 issue of “The New-York Journal of American History, “ the semiannual publication of the New-York Historical Society.