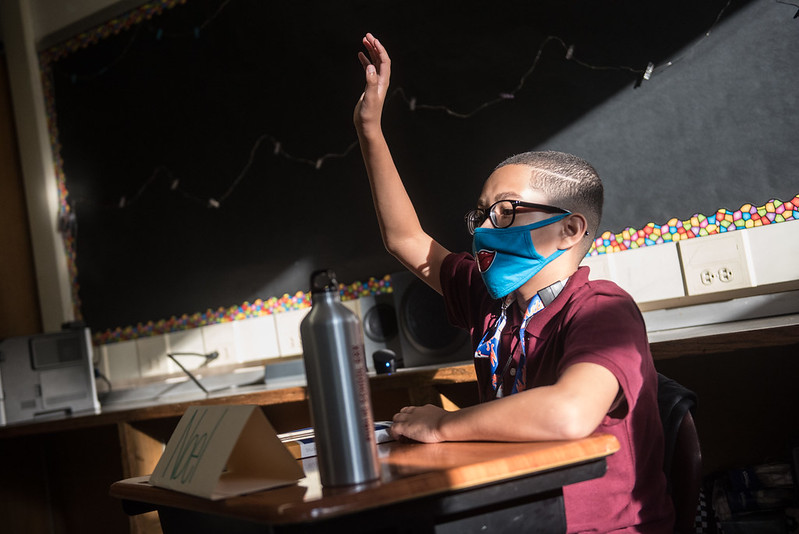

Students back in school amid a pandemic (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound effects for children across New York City and State, as well as their families, like the loss of a loved one, economic distress, food insecurity, and the shutdown of school buildings, switch to remote learning, and lack of in-person social connections.

During the first five months of the pandemic, an estimated 4,200 of 4 million children in the state lost a parent or caregiver to coronavirus, a rate of more than one out of every 1,000, according to a report by the United Hospital Fund and Boston Consulting Group released at the end of September. Over half of those children live in the Bronx, Brooklyn, or Queens.

The report found Black and Hispanic children were disproportionately impacted, with one of every 600 Black children and one of every 700 Hispanic children losing a parent or caregiver, compared to one of every 1,400 Asian children and one of every 1,500 white children.

The damage can be severe and long-lasting, with 23% of those children at risk of entering foster or kinship care and 50% at risk of falling into poverty, according to the report.

“How well a kid does after the loss of a parent really depends on the strength of their family support and also to some degree their financial stability,” said Dr. Jennifer Havens, a leader of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Health and Director of Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health for the Office of Behavioral Health at NYC Health + Hospitals, in an interview with Gotham Gazette.

The report found that between March and July, as a result of the pandemic, 325,000 children across the state were driven into or near poverty, which was linked to a severe jump in unemployment. Over 1 million children in the state had at least one parent become unemployed. Across the country, mental health-related visits to the emergency departments for children increased 24% and for teens increased 31% during March and April this year, compared to 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported.

Access to mental health care for young people, especially Black and Hispanic youth, is more important than ever. Yet, there are major issues with access, and the ramifications are already dire. While the de Blasio administration recently announced new steps to provide more mental health support to young people, especially in areas of the city hardest hit by COVID-19, large gaps remain and the scope of the problem may not be fully realized.

Suicide rates among youth and teens are higher than ever, and for ages 10-24, it’s the second leading cause of death behind unintentional injury. For Black youth, suicide rates are increasing faster compared to other racial groups, according to the American Psychological Association.

Black and Hispanic communities face critical roadblocks when it comes to accessing mental health care, such as lack of availability and of adequate health insurance, as well as language barriers, racism and other biases, and discrimination in treatment settings. Within their communities, people of color face higher levels of stigma for mental health challenges and for seeking treatment, and they are less likely to seek treatment as a result.

Tackling these disparities within mental health care and getting help to those who are most vulnerable is crucial, Dr. Havens said in the interview. “COVID is hitting low-wage earners the hardest, much harder than high-wage earners, so they’re already living on the edge, particularly in New York City, where it is so expensive to live,” she said. “And then to lose a parent or having a parent lose a job, it adds up to a lot of pressure and stress on a kid.”

Racial stressors also contribute to increased anxiety and depression, said Dr. Aaron Reilford, Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn and a professor in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “On one hand while it's really powerful for a lot of youth and families who are engaging in protests in regards to issues of police brutality, on some level it serves as a retraumatization,” said Dr. Reilford, at a Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York panel on children’s behavioral health in the age of COVID-19, of dealing with the fact that one can be subject to violence due to their skin color.

Changes in schooling, namely remote learning and blended remote/in-person instruction, may also be taking a mental health toll on students. According to a survey by Education Trust-New York, an education policy and advocacy organization, there is low satisfaction with remote learning among all parents but especially parents of color.

Mayor Bill de Blasio and city schools Chancellor Richard Carranza recently said that while the Department of Education has gotten hundreds of thousands of internet-enabled devices into kids’ hands, eight-plus months into the pandemic there were still roughly 60,000 students who had requested devices but did not yet have them. Only during the covid crisis did de Blasio order wireless internet to be installed in all homeless shelters with children living in them.

Attendance is also lower than in pre-COVID days, with an average of 85% for both remote and in-person instruction, according to numbers released on October 26 by the de Blasio administration, and there are major questions about how much engagement is happening for those who do “attend” remote school. About 300,000 students attended some in-person schooling, through a mix of in-person and remote classes, before city schools were temporarily closed on November 19 due to rising covid rates and de Blasio established a new plan for buildings to reopen and which students would be prioritized for in-person learning.

The high number of students not engaging in remote learning is striking, said Alice Bufkin, director of policy for child and adolescent health at Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, in an interview, referring to an attendance rate of 87.9% for online classes, which some say is misleadingly high because of questions around what counts as present. “Those are the children most at risk of not having access to the internet or being in a crowded household. Maybe they don’t have the privacy they need or the device they need,” she said. “There are all these challenges disproportionately impacting Black and brown children who are already facing challenges from covid.”

New York State spends the most per student on education in the country, $28,000 annually on average, Chalkbeat reported. During the 2017-2018 year, there were about 2,800 full-time guidance counselors and 1,300 full-time social workers within the city school system, according to a report by the Children’s Defense Fund of New York, for more than 1 million students at roughly 1,600 schools. The report states about 41 public schools didn’t have a guidance counselor or social worker, 141 schools didn’t have a guidance counselor, and 241 schools didn’t have a full-time guidance counselor. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 1 counselor to 250 students, but at the time about 900 New York City schools out of 1,600 had surpassed the ratio.

The lack of guidance counselors and social workers can have long-lasting effects on the city’s youth, more so during the stressors of a deadly pandemic, massive unemployment increases, school shutdowns, increasing violent crime, and a movement for racial justice. Not only do counselors provide behavioral health services and resources, they address a wide range of issues and challenges students face and assist them in applying for middle or high school and college. Social workers are among those who can both provide and recommend treatment and services for students.

Stepping in to support children’s behavioral health and providing resources while they’re young makes a difference, said Bufkin. “Children are resilient. If we can get them early enough and provide them with the support that they need, we can see them recover and go on to have healthy and successful lives,” said Bufkin.

Access to adequate mental health care within the school system is crucial, said Dr. Reilford, who is also a clinical assistant professor at NYU’s medical school. “For mental health services, in particular, you need to go where kids are,” said Dr. Reilford in the interview with Gotham Gazette. “Kids are at school, so if you set up a system where you can actually engage kids and adolescents and provide treatment at the schools, while you won’t be able to hit everyone, you’re certainly hitting much more than if you just relied on them walking into a doctor’s office,” he said.

In August, prior to schools reopening, the Department of Education released the Bridge to School plan to support wellness among students and school staff. At a press conference held by the mayor and chancellor, Deputy Chancellor LaShawn Robinson said 45,000 educators were trained in trauma-informed care and teletherapy was increased within the school system.

To address the emotional toll of covid, school shutdowns, and more on students, de Blasio and First Lady Chirlane McCray announced on October 22 a new initiative to increase mental health support for students in neighborhoods hardest hit by the pandemic. Current mental health workers will undergo the School Mental Health Specialist Program, which was converted from an existing consultant program that hired licensed social workers to work with schools in improving their mental health resources and plans, to become specialists and provide trauma-informed group work to students across 350 schools.

“Now, more than ever, we want all of our students to know that they are not alone, and there are compassionate, trained professionals ready to help them process anxiety, grief and trauma that may have intensified during the pandemic,” McCray said in a press release. “Parents and educators in our communities hardest hit by COVID-19 have called out for this kind of direct support and we are responding.”

The new initiative states specialists would begin assisting up to five schools in late October, as well as delivering mental health information to parents, caregivers, and school staff to address students’ needs. The city’s public schools are also partnering up with the city’s public hospital system, NYC Health + Hospitals, connecting 26 schools to outpatient mental health clinics where services such as ongoing therapy, psychiatric evaluation, medication management, and more are available.

The specialist program is managed by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in partnership with the Department of Education and is overlooked by ThriveNYC. “The $8.7 million Fiscal Year 2021 budget for the Consultant Program will be entirely converted to support the Specialist program, with the new direct service model requiring no additional costs,” the press release states. The Mayor’s Fund, a city-affiliated nonprofit McCray chairs, eased the transition into the new program by raising $35,000 to cover training and material costs.

In response to the alarming CDC numbers about increasing mental health-related visits to emergency departments for children, the Healthy Minds, Healthy Kids Campaign, a coalition of behavioral health advocates working towards high quality services for children in New York, pointed out that the situation is even more dire. “What’s worse, we know these alarming figures don’t paint the full picture of the tens of thousands of children grappling with increased anxiety and depression as a result of the unprecedented devastation, housing insecurity, social isolation, and disrupted schooling born from COVID-19,” the campaign said in a November statement.

The campaign asked the New York state government to address the mental health needs of children by ending budget cuts and increasing investments in behavioral health services, and closing the digital divide to ensure equitable access to telehealth services.

“There’s an approach that the city and the state take, which is we’ll cut a little here in education, we’ll cut a little here in health and we'll cut a little in social services so that way they're not cutting too much from any one area. But the reality is, the families receiving those services are all the same families, and it’s affecting the same communities,” said Bufkin, referring to communities of color and low-income communities.

The New York City Department of Education has faced challenges from the state. New York State was granted $716.9 million in federal aid to pass along to the city, but in April Governor Andrew Cuomo cut precisely $716.9 million in state funding from the city’s public schools, Chalkbeat reported, keeping the education budget stable. The state government also withheld 20% of local aid which resulted in no payments to school districts but that money was soon released after the teachers union sued the governor. With no bailout from the federal government, public schools could face immense cuts in funding in the near future, resulting in mass layoffs.

The mayor had proposed around $642 million in budget cuts for schools back in April, but much of that funding was restored in the final adopted budget, according to Chalkbeat reporting, including restoration of proposed cuts like $100 million in Fair Student Funding, a program that finances schools in need, $11 million from Single Shepard, a counseling program for middle schoolers, and $5 million set aside for social workers in schools.

Some cuts did get implemented in the budget, as Chalkbeat reported, including $40 million to school allocations that pay for services like social workers, restorative justice programs, and more. The borough field support offices that assist English language learners and students with disabilities also faced a $20 million reduction.

Another budget cut directly impacting mental health services was the reduction of $6 million in community school contracts, which also lost a $3 million grant from the city. Community schools “offer wrap-around supports for students and families, including upstream prevention services like food pantries and benefit enrollment help, in addition to direct mental health services in the form of counselors, social workers and school-based mental health clinics,” according to a brief on budget cuts towards behavioral health services, on which Bufkin contributed.

“We certainly can't see an improvement in access,” Bufkin said, “if we are at the same time cutting back on the services we know are so important for children to get the behavioral support they need.”

***

By Afia Eama, Gotham Gazette

@afia_eam @GothamGazette