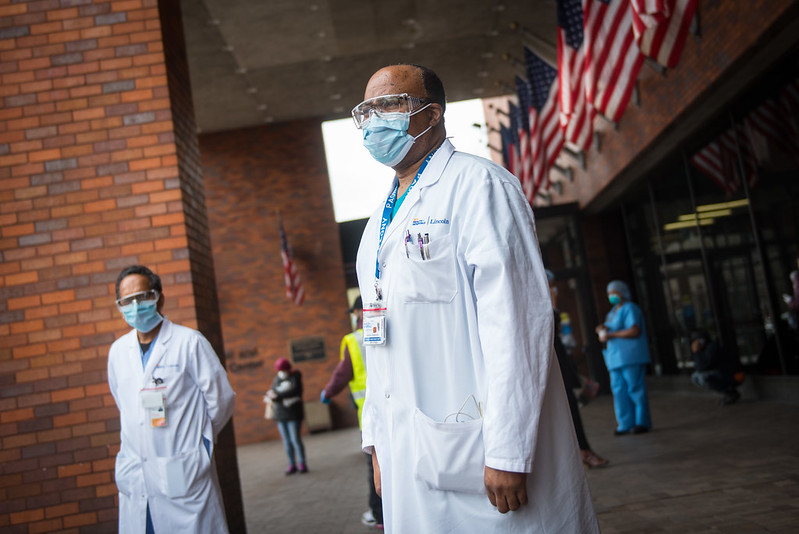

Emergency rooms are overflowing amid the coronavirus outbreak (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

[This is part two of a two-part series. Read part one: A 'Human Rights Tragedy' Unfolding - Part I: Racial Bias and Life-Saving Care During the Coronavirus Pandemic]

Dr. Yomaris Peña begins each day at 4:30 a.m. as a primary care provider in Washington Heights, where she sees patients back to back until she gets home at 6 p.m. After a cleansing ritual, which includes washing her shoes with Clorox and water, she says she begins reviewing charts and answering phone calls, emails, and social media posts from patients until she goes to sleep. This has been her new reality for the last four weeks.

She answers questions, monitors symptoms, and offers as much guidance as she can to her patients, who are mostly Hispanic and on Medicaid, and many of whom -- because of barriers to health care associated with racism and poverty -- would otherwise seek care in the emergency room, she says. Peña is worried that if she and other doctors on the ground in underserved communities don't meet the new demand, the city's hospital system would "collapse."

"We are the gatekeepers out there, the primary care providers," she said in a phone interview after she got home from work one day recently.

Emergency rooms are frequently the first and only point of contact with the health-care system for people who are uninsured or underinsured, lack transportation options, or are forced to prioritize daily stresses related to food, childcare, and housing. These constraints often fall along lines of race and are compounded by mistrust in a medical system fraught with bias and racialized health disparities.

As the coronavirus outbreak chokes the city's emergency rooms, those populations are facing diminishing options for adequate or even life-saving medical attention, threatening to exacerbate the crisis' already outsized impact on poor people and people of color.

Those who can are now flooding primary and urgent care facilities, according to doctors on those frontlines. The rest are left without any care at all if they aren't admitted to the hospital through the ER -- a now-common scenario for all but the most dire COVID-19 patients. With virtually no connection to the health-care system they are at risk of being untreated, and uncounted in the virus' final death toll.

"What we've noticed is that we're definitely seeing more black and brown patients and less white patients over the last few weeks," said Dr. Uche Blackstock, an emergency medicine-trained physician who works part-time for a large citywide urgent care provider at several locations in Central Brooklyn and was referring to clientele there. She is also the founder of Advancing Health Equity, which consults with medical institutions on structural racism and unconscious bias.

"It's even to the point where some of our sites that are in more white affluent areas have closed because the volume is so low," she said of urgent care facilities during the outbreak. "And we've had to shift staffing over to the sites that are in black or brown areas because at those sites the volume has soared."

While urgent care before the pandemic was typically for benign ailments like sore throats and minor cuts, Blackstock says she and her colleagues are now frequently seeing serious cases of cough, fever, and shortness of breath -- all COVID-19 symptoms -- sometimes on repeated visits. She regularly sees patients so sick she sends them to the ER, she said.

The situation is revealing just how essential primary and urgent care providers are in navigating what appears to be a very narrow window when an individual's chances of being admitted to the hospital are highest.

Government and public health officials are advising people to stay home unless they face severe coronavirus symptoms, like shortness of breath. Admission in many emergency departments is now frequently based on whether a patient needs intubation or is likely to quickly deteriorate.

With hospital resources, beds, and staff so scarce, primary care doctors are forced to monitor patients' symptoms and refer them to the ER only when they become life-threatening. Urgent care doctors typically don't have the ability to monitor and follow-up with patients, so they must make the weighty decision whether to send someone to the ER to try to be treated or home until their symptoms worsen.

"I have people that I sent to the ER and…a number of them, even if they have low oxygen, are sent home because there is not enough resources for everybody," Blackstock said. Even if a patient is short of breath, if they can go without being put on oxygen, they may be deemed healthy enough to go home. "It's those people in the grey area when they go home, what happens if they do deteriorate."

"If there is a situation where someone is sent home, that they will end up dying at home definitely is a chance," she added. "They may not want to return because they were already sent home once."

Two-hundred New Yorkers are dying at home daily, compared to between 20 and 25 before the outbreak, according to the city's medical examiner's office, as Gothamist first reported.

Significant public attention has focused on the disproportionate impact the outbreak has had on communities of color, particularly because of heightened exposure, underlying health conditions and barriers to care, crowded conditions, and the city’s and state's approach to administering coronavirus testing.

As of April 12, the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reported that 6,182 people had died from COVID-19 in New York City. According to partial data released on April 6, reflecting 63 percent of the reported deaths at the time, Hispanic and Latino New Yorkers died at the highest rates, followed by black, white, and Asian New Yorkers. In total, Hispanic and black New Yorkers made up 62 percent of fatalities, despite accounting for 51 percent of the city's population.

On Thursday, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced the state would be opening five new testing sites in "minority communities" in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. In late March, Cuomo and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie of the Bronx opened a mobile testing center in the Northeast section of the borough. On Sunday, Mayor Bill de Blasio said a new testing site would open in each of the five boroughs to address the "inequality." This builds on a four-point plan he released after the partial racial impact data was made public, which he says includes shoring up public hospitals with needed resources, a multi-language public education campaign, and expanding community-based and tele-healthcare.

Cuomo and de Blasio have both been focused on acquiring ventilators for ICU beds and expanding overall hospital capacity, and the governor and mayor have made these counts part of their daily briefings during the outbreak.

Less attention has been paid to the circumstances of populations who rely on emergency departments for care and the external triage role now being played by primary and urgent care physicians.

Representatives for Cuomo and the State Department of Health did not return requests for information about what if any additional funding is going to primary care providers to meet the new demand and to community-based organizations for health-care outreach.

The New York City Health Department told Gotham Gazette it is polling a sample of providers to find out if they are open and providing telemedicine. An email statement says the department "will continue to communicate with the community and providers on telemedicine reimbursement, health insurance availability for patients who may have lost insurance, as well as additional information related to COVID and to financial relief."

Four weeks since the mayor issued a state of emergency, the city Health Department is not actively conducting patient outreach but has plans to, the statement said: "In the coming weeks, we will be offering assistance to practices involved in our primary care programming to identify patients at higher risk for COVID-19 and conduct patient outreach. We will also offer assistance to establish telemedicine documentation and workflows to be billable."

In March, the city extended and loosened requirements on human services contracts, including for community-based organizations providing healthcare, so they could continue to maintain operations.

As long as the outbreak continues, many people who may need medical treatment for conditions other than COVID-19 may not seek it for fear of catching the coronavirus in a hospital. Others, without alternative forms of care, may be unnecessarily exposing themselves to the virus in pursuit of avoidable emergency treatment in a crowded ER.

"For a lot of communities of African descent, the emergency room is the first point of contact with the healthcare system," said Lurie Daniel Favors, a civil rights attorney and executive director of the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn. "When you are in low-wage work or no-wage work and you don't have a primary care physician and you're told to contact your medical provider to see if you need testing, for a lot of people that medical provider is the emergency room."

"Obviously that triggers a whole series of cascading impacts because we don't want people just showing up to emergency rooms because of what we're seeing happening with the overburdening of the healthcare system," she said. "Yet when you don't have the facilities within black and brown communities to really provide basic care that's basically what you're looking at."

Black and Hispanic people visit the ER in New York State at a higher rate than white people: roughly 57 visits per 100 black New Yorkers, compared with 38 visits (Hispanic), and 23 visits (white), according to state Department of Health data from 2013. At the time about 72 percent of ER visits were considered "potentially preventable," meaning "they could have been the result of a deficiency in ambulatory care," according to a report accompanying the data.

Access to health insurance is a leading reason people rely on the emergency room. In fiscal year 2019, 11.6 percent of New York City residents did not have health insurance, according to the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

"By law the only right to healthcare anyone in this country has (other than prisoners, which is a whole other issue) is in an emergency room," said Dr. Alison Bateman-House, assistant professor in the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU School of Medicine, referring to the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. "People who have nowhere else to go, that's where they are going to go."

Being uninsured or underinsured also means many people forgo routine care like annual physicals or regular medication because their copays and deductibles are too high.

But there are other socio-economic reasons outside of insurance that people rely on the emergency room, according to Dr. Jorge Petit, CEO of Coordinated Behavioral Health, the state's largest behavioral health provider. Medicaid recipients, who in New York State are disproportionately black and Hispanic, also frequently seek emergency care considered avoidable because of "issues around stigma, and language barriers, and transportation issues," he said.

According to the 2013 DOH report, Medicaid was the primary payer in roughly 38 percent of ER visits.

"There are a whole host of reasons that even those who are insured aren't getting appropriate care. I think that, again, disproportionately falls on black and brown populations," Petit said.

Without primary care to screen and mitigate symptoms, when people end up seeking care it is for advanced conditions. "As their only method of dealing with their medical issues, it's happening in an acute state and through the emergency departments," Petit said.

Particularly among African-Americans, a long history of racial bias in medicine has sown distrust in health-care institutions, according to Dr. Blackstock, the urgent care doctor.

She said in recent years, urgent care centers have increasingly become an alternative to ERs because they are quick and accept a wide range of payments. In recent weeks, that trend has exploded, she said. As reports of overcrowded hospitals and long waits in the ER continue, Blackstock said, New Yorkers afraid of contracting the coronavirus are going to urgent care clinics in lieu of hospitals.

With hospital resources spread so thin, Blackstone worries patients without primary care will be among the growing number of COVID-19 patients who die at home, many of whom are not yet being counted in the city's official tally.

"It would be valid to be concerned about those communities where people if they go to the emergency department and are turned away, may not return if their condition worsens because they think they may not receive good care or it may not be worth it to return," she said.

"We could see increased cases of mortality if we don't continue this triage and screenings and talking to our patients through telemedicine," said Dr. Peña, the primary care doctor in Washington Heights, who is part of SOMOS, a network of close to 2,500 providers serving Medicaid recipients throughout New York City.

"This is as we speak, like we're talking right now,” Peña said, “and I have a lot of calls that I need to answer so that they don't go to the emergency department for things that they shouldn't be there for right now."

[This is part two of a two-part series. Revisit part one: A 'Human Rights Tragedy' Unfolding - Part I: Racial Bias and Life-Saving Care During the Coronavirus Pandemic]

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette