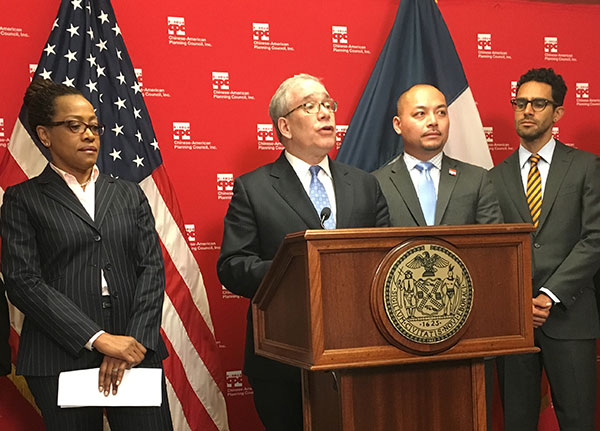

Comptroller Stringer (photo: Samar Khurshid/Gotham Gazette)

The 15 neighborhoods that experienced the highest rates of gentrification in the city between 2000 and 2015 showed a monumental increase in new businesses and job growth but with an inequitable distribution of the accompanying benefits, according to a new analysis released Tuesday by Comptroller Scott Stringer.

Stringer’s first-of-its-kind report, titled “The New Geography of Jobs: A Blueprint for Strengthening NYC Neighborhoods,” looked at economic activity in 15 gentrifying neighborhoods and examined trends in employment and entrepreneurial activity by industry, age, racial and ethnic groups. The neighborhoods were those identified by the NYU Furman Center in an analysis of 55 “sub-borough areas” in 2015. Of these, 22 were classified as lower income and 33 as higher income. The gentrifying neighborhoods were those that were lower income in 1990 and had experienced rent increases beyond the median neighborhood.

“We need to create an economy based on fairness,” Stringer said, speaking at the Chinese-American Planning Council on the Lower East Side. Stringer cited CPC’s work in the Lower East Side Employment Network, a successful workforce development approach that he said should be the model for other neighborhoods. “We want to be able to lift up all groups of people and everyone in our communities. I believe this is about the need to support the idea of local wealth creation and we can only do that with innovative, collaborative and community-centric solutions,” the comptroller added.

As economic activity increases in previously under-developed and lower-income neighborhoods, Stringer believes, the resulting opportunity, profits, and benefits should be experienced more evenly by all groups of residents.

The number of businesses in the city grew from 203,698 to 237,198 in the 15-year period, the report found, with increased activity in the boroughs outside Manhattan. In Downtown and Midtown Manhattan, which have traditionally seen large concentrations of the city’s economic activity, the share of total businesses fell from 39 percent to 31 percent. But in the 15 gentrifying neighborhoods -- which include East and Central Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, Prospect Heights, Bushwick, Sunset Park, Brownsville and Ocean Hill -- there was a 45 percent increase in the number of businesses from 29,132 in 2000 to 42,261 in 2015.

Although lower income communities saw greater growth than higher income districts across myriad industries, that growth was unevenly distributed. The report notes that while people of color own 34 percent of the city’s businesses, an uptick from years past, their share in the city’s overall economy, 16 percent of revenue and 21 percent of employment, remains relatively low. Black New Yorkers remain massively underrepresented, accounting for 22 percent of the city’s population but only owning 3 percent of businesses.

The report also found that 17.2 percent of young adults, between 18 and 24 years old, were out of school and out of work (OSOW) in 2015, with racial and ethnic disparities in those numbers. Among OSOW youth in gentrifying neighborhoods, black and Hispanic youth represented 21 percent each, while white youth made up 12 percent.

Stringer makes a number of recommendations in the report, aimed at connecting economic growth in a neighborhood to its residents. These include creating local network coordinators at workforce development providers to connect businesses with local job seekers; creating uniform assessments to evaluate and prepare job-seekers for the labor market; and assisting entrepreneurs and startups in scaling up their operations and setting up brick-and-mortar establishments; among other proposals.

“My message today is this: skylines change, creation is a good thing,” Stringer said. “But we have to do a better job of harnessing this economic power in a way that serves everyone. We need to focus not on prices and not just on rent, but we also need to work on wealth creation, on linking long-term residents with new emerging jobs.”

The comptroller noted, in response to a reporter, that housing affordability is still a crucial component of gentrification but emphasized the need to recognize changing demographics and economic challenges in those same neighborhoods. “What we need is a much more forceful workforce development plan because our data shows that there’s real possibility,” Stringer said, “but right now, for many communities, for many people, there’s a real disconnect between some of the benefits of changing neighborhoods, and it’s not filtering down to long-term residents.”

Stringer said this more robust city response to workforce development issues should be part of proposed rezonings that are being studied across the city. The de Blasio administration and local communities are in the process of developing plans to add development, population density, housing -- including affordable units, and neighborhood-specific changes like additional school seats and new parks, for example, to a variety of areas throughout the city. One plan, for East New York, was passed a year ago and is in the process of implementation. Others have moved slowly or stalled, though several, including for East Harlem, may be moving ahead more quickly soon.

Stakeholders in the East New York rezoning, including local Council Member Rafael Espinal, pushed strongly for workforce development initiatives to be included in the final plan, particularly the establishment of a city-run Workforce1 career center that opened in December. Similar efforts are also underway in other neighborhoods facing proposed rezonings, with community advocates insisting that jobs created by development should go to local residents.

Asked by Gotham Gazette about Mayor Bill de Blasio’s recently announced plan to create 100,000 “good paying jobs” in the next ten years, Stringer had some cutting advice. “Anytime you want to say, ‘I can create 100,000 jobs,’ sure that’s OK, that’s a good thing,” he said, “but now we have to look at our emerging economies in the boroughs and what kinds of jobs are being created and are we matching good jobs with the citizens in those communities. And if we’re not, and we’re clearly not with communities of color in some of these neighborhoods, well what will you do about it? Can’t just say we’re gonna create jobs for people who can’t access those jobs? That’s not right.”

[Related: Part of Rezoning Plan, City Opens New Career Center in East New York]

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette