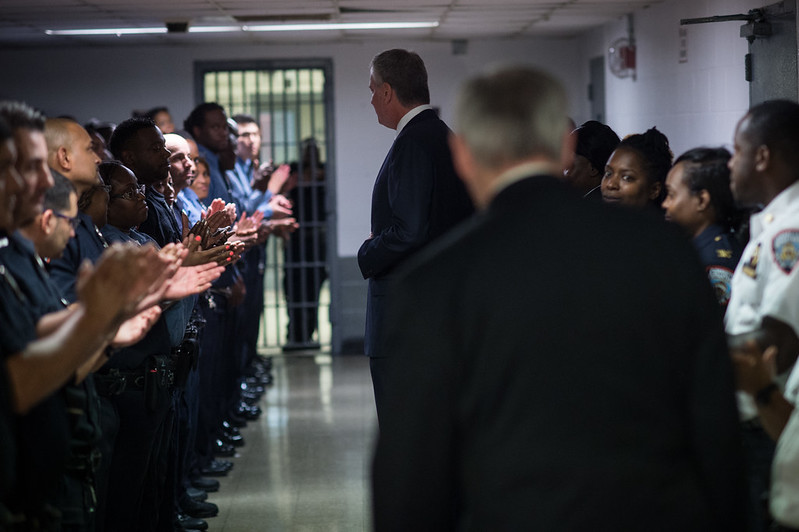

On Rikers Island (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

The narrow bridge to Rikers Island still puts a knot in my stomach. In the late 1980s, I spent two years behind bars in one of the eight active jails on Rikers. Back then, crossing that bridge meant disappearing from society and entering a world defined by violence and inhumanity.

Little has changed. These days, I visit Rikers regularly as vice chair of the Board of Correction, the independent oversight body for New York City jails, and as executive vice president of the Fortune Society, an organization that helps people succeed when they come home from jail and prison.

Rikers still sends one message to everyone who crosses that bridge, no matter if you’re a correction officer, incarcerated person, or visitor: you are worthless. People feel like animals, caged and mistreated. They react accordingly.

During my first year at Rikers, this combustible mix exploded into a riot led by people brought down from upstate prisons for legal proceedings in the city. In theory, these men should have been happy to be closer to their families. But to visit Rikers, their loved ones still had to spend all day traveling to the island for just an hour together—as my father once did when I was jailed on Rikers. I hated to see the effect on him so much that I asked him not to come back.

The men from the state prisons experienced the same pain. The anger they felt from mistreatment by correction officers and the brutal physical conditions of Rikers drove them to barricade themselves in their housing unit and erupt in the mess hall.

Thirty years later, violence still permeates Rikers, where hints of disrespect are met with force. The jails remain inaccessible to families, lawyers, and other much-needed connections to the outside world. The conditions are still dehumanizing. During the July heatwave, I toured the jail where I was held so many years ago. The cinder blocks and metal worked like an oven. Officers patrolled in shirts drenched with sweat. A few cheap fans pushed around hot air, never reaching the people sweltering in their cells or stationed at their posts.

The vast majority of people at Rikers are awaiting trial, as I was. Almost all of them are people of color. Every day, nearly 800 people must be bussed to and from courts in the boroughs at cost of $41 million a year.

Moving around inside the poorly-designed jails is also difficult, requiring an officer escort down hallways that can stretch hundreds of yards. Too often, incarcerated people do not make it to medical appointments, family visits, recreation, commissary, and court. Cases are delayed, anger rises, and health suffers.

We can change this. In April 2017, after years of pressure, Mayor Bill de Blasio committed to shutting down the Rikers jails, reducing the number of people locked up by half or more, and holding this smaller jail population in facilities near the borough courthouses.

Since then, the number of people in jail has dropped by thousands. Our city remains as safe as ever, demonstrating we do not need mass incarceration to achieve safety.

This week, the City Council will vote whether to authorize four redesigned borough jails that will enable the permanent closure of the eight jails on Rikers and the jail barge moored to Hunts Point.

This plan is a once-in-a-generation chance to close Rikers and replace it with something far better, and far smaller. But no one should underestimate how hard it is to close an institution like Rikers.

It will require more changes to police and district attorney practices. It will take continued reforms in Albany, like passing the Less Is More Act to fix New York State’s broken parole system.

It will also require approval of the smaller borough system under consideration by the City Council. The initial designs for these facilities would promote safety and facilitate re-entry. Located much closer to courthouses and public transit, they would speed up cases and increase access for attorneys, family members, and others. They would be more accountable to oversight, leading to better conditions.

In final negotiations, the Council can improve the current plan by securing major community investments, so people never end up in jail in the first place. But this plan has to pass or we will be stuck with the horrors of Rikers for decades to come. We cannot allow the quest for the perfect to stop us from doing what is right.

Since I came home to the Bronx, I have dedicated myself to helping others succeed. The sprawling, unmanageable, and violent jails on Rikers undermine that goal and our communities. Let’s end this disgraceful chapter in our history.

***

Stanley Richards is Executive Vice President at The Fortune Society, a member of the Independent Commission on Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, and a member of the Justice Implementation Task Force. On Twitter @Stan_Fortune of @thefortunesoc & @MoreJustNYC

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.