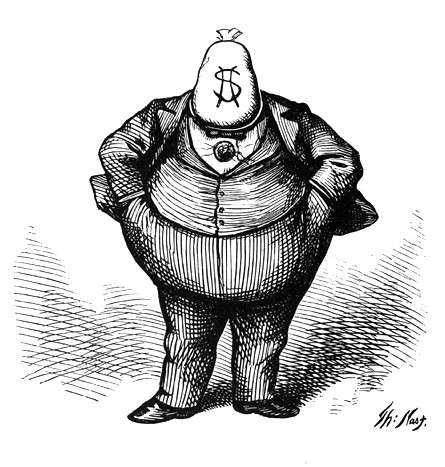

Cartoonist Thomas Nast's classic portrayal of the "fat cat" politician.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s pledge of campaign finance reform has widespread support from New Yorkers fed up with a system in which wealthy individuals, businesses and unions overwhelmingly underwrite the cost of running for state office, thereby endearing themselves to lawmakers.

Much of the discussion over campaign finance reform has revolved around the issue of public financing. A public financing system similar to the one in New York City would encourage average New Yorkers to play a role in funding campaigns, since their donations would be magnified through a public match.

It is important to note that public financing is only one part of New York City’s exemplary system. While their laws and regulations are better than the state’s in a variety of ways, two of them — lower limits and a functioning administrative body — are essential parts of any bill hoping to replicate the City’s success.

Most of the state legislative proposals would significantly lower contribution limits for participating candidates by bringing them close to the more reasonable federal levels.

These lower limits, however, need to apply whether or not candidates choose to participate in a public financing system. If statewide candidates can continue to receive donations of up to $60,800 per donor, will there be any incentive to opt in to the public finance system?

Even these astronomical limits can be easily avoided. Limited Liability Companies are bizarrely exempted from the regular corporate donation cap and treated as individuals. Further, businesses with separately incorporated divisions may give the maximum amount through each division.

Developer Leonard Litwin exploited both of these loopholes to give nearly a million dollars in the past six months, and so far this election cycle has given the governor more than four times the limit usually placed on individuals.

Political parties can receive $102,300 per year from each donor.

However, the five largest parties in the state all have “housekeeping committee” accounts that can receive unlimited donations, even from those who maxed out on this six-figure limit.

While use of this money is ostensibly limited to non-electoral purposes, it goes toward expenditures that few logical individuals would believe exist outside the realm of campaigning, such as the hiring of campaign staffers, paying rent on campaign offices, and running push-polls on behalf of candidates campaigning for office.

New York’s Republican Party has recently proved how fungible this money can be by doing the functional equivalent of laundering housekeeping funds through two different committees and transmuting it into hard money.

Lowering limits on party fundraising is just as important as doing so for candidates: even those candidates who participate in a public financing system could solicit huge checks on behalf of parties with the tacit understanding that this money would eventually be transferred their way or spent on their race.

It’s also clear that administration and enforcement of the campaign finance laws need to taken out of the hands of the Board of Elections, an agency designed to be partisan. The state Board is incapable of taking any action that goes against the will of members in good standing of either of the major parties.

An example is that each year hundreds of donors give more money than they are allowed by our incredibly lax contribution limits.

Yet the state Board never investigates these most basic violations of the current law — even when NYPIRG has, on several occasions, attempted to help them by providing lists of donors who have crossed the legal threshold. The Board has never taken action against any of these individuals or businesses, many of whom are annual violators.

The state Board is also an anemic administrator. Some recent evidence can be found in the Board’s bungling of a statutory requirement to create rules for the disclosure of independent expenditures, such as those made by Super PACs, by January 1st of this year. Its draft proposal was nearly two months late and failed to capture the spending this law sought to expose. As of the beginning of August it was still not finalized.

With the Board’s history of failure in administering our current weak laws, there’s simply no reason to believe they would be capable of overseeing a new, $50 million per year public financing system.

There are other reforms that NYPIRG and other watchdog groups believe should be part of a campaign finance package, including requiring better disclosure, such as the names of donors’ employers and the identification of “bundlers,” and a lowering of limits for candidates in some of the larger localities in the state.

There will also be several areas in a potential bill that could create loopholes, including letting incumbents carry over their huge war chests into future elections.

These details can be worked out when serious talks about passing a bill commence.

A vigorous public financing system could help New York become an exemplar of participatory democracy.

However, New Yorkers shouldn’t be asked to pay for a public campaign finance system that doesn’t really promise to dramatically reduce the influence of special interests in political campaigns.

We have to get it right, since whatever program is created is likely the one we’ll live with for the foreseeable future: legislators won’t rush to work out the glitches in a system that helps perpetuate their 98% reelection rate.

New Yorkers should echo the governor’s call for overhauling the state’s shameful campaign finance system by exerting pressure on legislators to pass truly comprehensive campaign finance reform.

They should be mindful, however, that any proposals include the reforms needed to make a public financing system successful.

_____

Bill Mahoney is the legislative operations and research coordinator for New York Public Interest Research Group