Trump Decimated Refugee Admittance; Biden Promises Massive Expansion — What it Means in New York

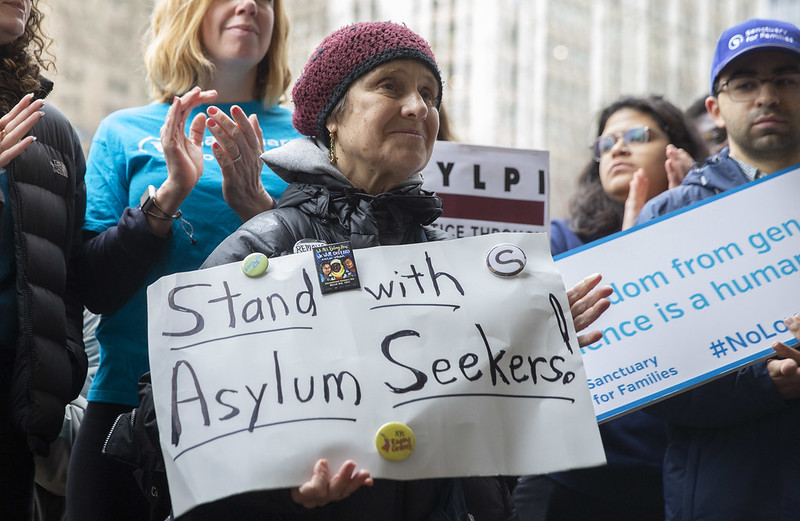

A New York City rally in support of asylum-seeking refugees (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

As part of a systematic dismantling of providing asylum to refugees in the United States, the Trump administration in October 2020 reduced the cap on resettling refugees in the country to just 15,000 for fiscal year 2021, which runs from October 1, 2020 to September 30, 2021, down from 18,000 for fiscal year 2020, and from 85,000 in the last year of the Obama administration.

These reductions have a significant impact not only on those seeking refuge in the United States, but also on New York, where many refugees often settle, whether in New York City or places including Erie County and Rochester, where there are significant refugee populations from countries such as Afghanistan and Democratic Republic of Congo. About 1,800 refugees are resettled every year and New York State provides millions of dollars in funding annually to refugee resettlement organizations.

Trump’s move to limit refugees -- people fleeing persecution and armed conflicts -- into the country is part of a larger administration push to limit legal and illegal immigration and to create a broadly xenophobic and nationalistic policy.

The outgoing Republican president, recently defeated by former Vice President Joe Biden, has repeatedly publicly railed against Congressional Rep. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, who came to the country in 1995 as a refugee from Somalia.

Along with painting refugees as unwelcome outsiders, Trump has argued for the lower refugee cap by indicating he believes it would effectively give more jobs to Americans and save the federal government money.

These claims have been debunked: federal funding for each refugee resettled is limited to only $1,000 if the resettlement is done within or by 90 days, and refugees often initially fill low-skill jobs, with little discernible impact on the larger labor market.

President-elect Biden, a Democrat set to take office January 20, has promised to work with Congress to ensure the United States admits a minimum of 95,000 refugees each year. On June 20, commemorated as World Refugee Day, Biden pledged he would increase the number of refugees admitted to the U.S. annually to 125,000, which would be a historic high.

But it could take months to years to be able to start admitting so many refugees, mostly because so few are in the pipeline after Trump’s policies. To be admitted into the U.S., refugees go through several rounds of background checks, screenings, and interviews under U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services as well as ongoing vetting by a variety of intelligence agencies including the FBI and CIA. This process can take up to two years.

Along with the damage inflicted on those seeking refuge in the United States who won’t be allowed to resettle in this country, the decimation of the United States’ refugee program and its impact on New York has largely left refugee resettlement agencies dealing with the fallout.

But another significant challenge came from the current state budget, passed in early April amid major coronavirus-related challenges and question marks. Funding for the New York State Enhanced Settlement for Refugees Program (NYSESRP), which supports these non-profit agencies, was slashed by $1 million, cut in half from the $2 million allocated the previous year. Advocates have called for an increase to $4.9 million, but the state’s cuts have compounded the financial pressure on both NYSESRP agencies and agencies that don’t come under the NYSESRP. The state funds at least 11 organizations that have worked for a significant amount of time in refugee resettlement.

Shelly Callahan, Executive Director of The Center, a non-profit NYSESRP agency located in Utica, New York, said everything is in a state of flux at this moment. “Even if Biden wins, the damage this administration has done cannot be undone,” she said in late October. “To get back to the point where we can settle 110,000 refugees a year, it’s going to take a lot of time. We went from resettling 400 refugees before the cap was reduced, and this year we did 104. We also have huge lack-of-workforce issues across the state, we also get secondary migrants — refugees who come from other parts of the country. We’re not keeping at pace with the population growth that we need in these areas.”

There are high rates of secondary migration by refugees to New York, mostly from Texas and Tennessee, according to Callahan. While The Center and other resettlement agencies provide services to them as well, it is an additional stressor and a great deal of work for which they don’t receive funding from the government. New York is recognized as being hospitable and welcoming to refugees (and immigrants generally), and the NYSESRP funding was instituted after the Trump administration's actions in 2017.

The cut in state funding in the current fiscal year 2021 budget, Callahan said, makes a significant difference.

“For an agency like mine $2 million [in the state budget] meant $200,000 a year,” she said of the portion of overall state NYSESRP funding that her agency received until last year. “Even though the number of refugees has been cut significantly, our services have increased, especially when covid happened. But now, we have to find money from other places, reduce programs, and that won’t be good for the community.”

As for non-NYSESRP agencies, Isabel Miller, Executive Director at Saint’s Place, based in Pittsford, New York, is relying largely on donations from loyal philanthropists and emergency covid grants from the state. “When the [refugee] numbers started to decline, we made a pivot to focus on refugees that have already been resettled,” she said. “We haven’t had to stop our programs, though part-time staff were let go. Our peak was about four years ago where we helped 1,200 refugees, most from Cuba and Afghanistan. Once the latest lower cap was put into order, we are expecting maybe 120, and only 30 have arrived so far.”

“The pivot we made to focus on existing refugees in the area was not due to lack of funding, it was lack of refugees,” Miller continued. “If we didn’t make the pivot, we would not be of any use. We hear in different areas that people have cut back on staff significantly. We have a lot of volunteers of 150 refugees who help us, and just five others on staff. There are many refugees who have been vetted, but are not allowed to come into the country, so they’re just waiting.”

Anthony Farmer, a communications officer for the state’s Office of Temporary and Disability Services, under which the New York State Enhanced Services to Refugees Program (NYSESRP) functions, said that the program was created in response to the federal government severely limiting refugee admissions, something no other state has done. “NYSESRP has enabled refugee resettlement agencies across the state to continue actively serving refugees, in spite of the federal government’s callous action, with some even expanding their scope by serving refugees who have resettled more than five years ago,” he said in a statement.

State Senator Andrew Gounardes, a Brooklyn Democrat who has led the effort to increase state funding for resettlement and whose district is home to many Syrian refugees, among others, said in a statement to Gotham Gazette: "The gap in funding for refugee services will affect not just these families but the local economies of the communities in which they live. It is urgent that funding be restored as soon as possible."

Donald M. Kerwin Jr, Executive Director of the Center for Migration Studies, believes that “minimal infrastructure” must be in place for Biden to be able to successfully keep his promise to increase refugee numbers. “By minimal infrastructure, I mean vetting, the procedures that ideally shouldn’t take years,” he sad, “and a smoother process for them to resettle.”

***

by Divya Karthikeyan, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette @divya_krthk

New York Hospitals Brace for a Second Covid Wave. Are They Ready?

Lincoln Hospital staff (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

As public health officials eye a second major swell of COVID-19 infections and an increase in hospitalizations, New York's hospital systems have begun to brace for another flood of patients. The state has even opened a field hospital on Staten Island in response to rising numbers, a dismal reminder of the devastation of the spring.

In the months since the height of the pandemic in the spring, New York's health care institutions have been making preparations to try to avoid the same chaos and loss of life, which has been partially attributed to a lack of coordination. But in many areas, like before, hospital administrators and staff are just trying to stay one step ahead of the virus, keep staff safe, and maximize patient survival.

The city's hospital systems "faced an unprecedented situation for which no one was fully prepared," wrote City Comptroller Scott Stringer in a review, issued in July, of the city's public hospital system, which saw many of the most severe problems. "The lack of preparedness forced all players to improvise responses, sometimes successfully, sometimes not – but inevitably at a cost in human lives."

Hospital administrators have signaled to their staff, lawmakers, and the public that they don't believe a second covid wave in New York will be as bad as the first -- with lessons learned and months to upgrade facilities, stockpile supplies and ventilators, and develop so-called "surge plans" to be used in the event another round of mass admissions strains hospitals. But experts are questioning whether hospitals will have enough staff and personal protective equipment (PPE) if hospitals see the crisis levels of March, April, and May again, and even ICU nurses onboarding others are expressing doubt about the adequacy of a heavily-truncated training regimen. New York City and State are hoping to better balance patient loads across hospitals to avoid overwhelming any one facility, but no new system has been finalized and much remains unsettled about how a patient diversion program would operate.

In the spring, hospitals were overflowing with covid patients and, along with governments, struggling to procure enough PPE, particularly within Health + Hospitals, the city's network of public hospitals. Government and hospitals worked together to nearly double the state’s bed count from 53,000 to roughly 90,000, and though they were never all filled, there were concerns about the state’s ability to meet the upper projection of 140,000 hospital admissions.

To comply with an executive order from Governor Andrew Cuomo to increase capacity by 50%, hospitals rapidly converted offices and auditoriums into intensive care units; field hospitals were set up in convention centers like Javits, and the USNS Comfort, the Navy hospital ship, docked temporarily in the Hudson. Some facilities, like the now-infamous example of Elmhurst hospital in Queens, one of the city's 11 public hospitals, were overflowing while others had space. At the apex in April, the state had 90,000 additional health care workers, including 25,000 from other states.

More than 26,000 people are confirmed to have died from COVID-19 statewide. According to city data, over 24,000 New Yorkers have died of covid in the five boroughs, which includes unconfirmed but suspected covid deaths, or about 1 in 350 city dwellers.

The spring surge in patients meant hospitals needed more space for beds and more personnel to staff them, more supplies to protect or save both patients and staff, and the systems to manage the new, exhausting demands. Many of those systems remain in place or serve as the basis for current emergency plans, like the "NYC Strategic Reserve” PPE and ventilator 90-day stockpile ordered by Mayor Bill de Blasio that the city says is near completion. These issues were especially acute within the 11 public hospitals run by Health + Hospitals, according to Comptroller Stringer’s report, which had been requested by the governor and also pointed to underfunding by the state.

"All of our hospitals have learned from the devastating first wave of the pandemic and really poured their hearts and energies into preparing for the second surge, which we hope won't happen, but unfortunately we are at risk of given the numbers we are seeing," said New York City Health Commissioner Dave Chokshi, last week.

The next morning Mayor Bill de Blasio said "our hospital system is strong right now," but warned that it remained essential to work to keep covid numbers low and avoid strain on ICUs. At a recent City Council oversight hearing, city public health officials testified about lessons learned from the spring and preparations in place for a second wave, including by noting they now often use less invasive ventilation techniques and new protocols for stabilizing patients before transferring them.

The citywide seven-day average number of hospitalizations per day topped 80 admissions last week, three times what it was in August but still far below the thousands of daily admissions at the peak. As of Monday, 931 people were hospitalized due to COVID-19 citywide, of whom 196 were in intensive care. Test positivity has been ticking steadily upward since the summer and the city and state have begun shutting down key sectors of public life, like in-person schooling, a reprise of the conditions on the eve of the apex. Governor Cuomo, Mayor de Blasio, and others have been sounding the alarm that a second wave is staring New York in the face, and imploring New Yorkers to follow all guidelines.

"Rates go up, you overburden the hospital system, you overburden doctors, nurses...Numbers go up and people die. People die. Period. It is a mathematical equation," Cuomo said at a news conference on Sunday, warning rates could "easily" skyrocket for months "if we are irresponsible."

On Monday, Cuomo announced a field hospital would be opened on the site of South Beach Psychiatric Center in Staten Island in response to a dramatic rise in hospitalizations in New York's most isolated borough. "The hospitals have contacted us, and they say they need emergency beds on Staten Island," the governor said at a press briefing. "Remember when we had to set up field hospitals, emergency hospitals for additional capacity? Well, that's what we have to do on Staten Island.”

Throughout the pandemic, the state has functioned as a regulatory body, coordinating resources among public and private hospitals, suspending some requirements and setting new guidelines. As of August 6, emergency regulations from Cuomo's Department of Health establish the framework to reinstate many of the "surge and flex" provisions imposed at the end of March. Hospitals must have plans to expand capacity by 50%, manage mass casualties, and enlist workers in the event of another state of emergency. Each facility is required to stockpile 90 days worth of PPE.

To manage it all, the plan calls for the state health department to maintain a statewide data system and coordinate patient loads across New York's various hospital systems. In another serious outbreak, the state Department of Health may designate healthcare facilities as covid-priority "trauma centers."

In response, a loose organization of government agencies and private healthcare providers has taken shape across the city and state, mobilizing a massive operation that eight months in is still a bit of a leaky ship.

Space

A big focus in recent months has been upgrading spaces and preparing surge plans for the rapid conversion of hospital units and non-clinical space, the offices and auditoriums, into covid ICU wards.

While much of the space has reverted to its traditional use, officials have retained the knowledge to transform facilities and are building up the infrastructure to do it faster. New York City Health + Hospitals tripled ICU capacity by adding 760 ICU beds, some of which were made permanent, as was much of the digital roadmap for tracking them.

“NYC Health + Hospitals has been on the frontline of the COVID-19 crisis, providing the highest quality care to all New Yorkers in the face of an unprecedented global pandemic – and we stand at the ready to provide that care as we brace for a potential second surge," wrote Stephanie Guzman, a spokesperson for Health + Hospitals, in a statement to Gotham Gazette. "Since the spring surge, the public hospital system has made strategic enhancements in space, equipment and staffing to ensure each of its hospitals is even more prepared now to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients."

The city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has been working with public and private hospitals using federal grant money to support covid response and improvements at hospitals and long-term-care facilities. Facilities are incorporating design changes to support rapid unit conversion, like negative pressure rooms, which are used to help prevent the spread of the coronavirus through the air.

Health + Hospitals has increased piped oxygen and dialysis capacity to more easily turn beds into covid ICU beds. Hundreds of rooms have been modified to allow for physically distant patient monitoring with more to come soon, according to Guzman.

The city has some sites on stand-by, like the Roosevelt Island Medical Center, which was opened up this spring on the campus of NYC Health + Hospitals/Coler, where Mayor de Blasio announced plans to open 350 additional non-covid beds in March, which by April were also serving covid patients.

"[An]other thing we learned is that temporary field hospitals like the USS Comfort aren't going to be as effective as expanding the current sites or reopening sites like they did on Roosevelt Island," said New York City Council Member Carlina Rivera, chair of the Council hospitals committee, in an interview. The Comfort treated just 182 patients in its one-month stay docked off of midtown Manhattan.

Systems

One of the failures of the first wave was a lack of coordination within and among the public and private hospital systems to balance patient loads.

At Elmhurst Hospital, a Health + Hospitals facility in Queens, health-care professionals were overrun with patients -- one day at the end of March seeing 13 deaths in 24 hours -- despite close to 900 beds open across the public system and 3,500 total beds in New York City, counting private hospitals. The surrounding neighborhoods of Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, and Corona had some of the highest covid mortality rates in the city.

"[T]he problem the Elmhurst situation exposed was not one of hospital capacity, but one of patient load management across all hospitals and hospital systems," reads an excerpt from state Department of Health regulations issued in August and November.

"When it came to patient transfers, I thought, we really wanted the whole system to operate as one," Council Member Rivera said. "And we heard as much in some of the press conferences. But in practice it didn't truly become a reality."

To avoid the Elmhurst syndrome, the city is working with Emergency Medical Services, a division of the state Health Department, and the Greater New York Hospital Association, a consortium of hospital networks, to develop a "unified approach" to balancing patients, according to Victoria Merlino, a spokesperson for DOHMH. The protocol would mean "moving patients from one facility to others that have more capacity available and deferring EMS to overcrowded hospitals when possible," Merlino wrote.

But it is not ready, and there are few details about how it would work in practice. EMT staffing and shortages were ongoing concerns during the siren-heavy months of the first wave, and now will be an even more central component of the city's emergency response if the system is to better balance admissions.

While the state Health Department's emergency regulations say the department "shall coordinate with health care facilities to balance individual facility patient load," the approach appears to be largely decentralized.

"While the determination of when to transfer a patient or divert EMS resources is a local one, the Department monitors facility capacity and is available to assist with the logistics of making a transfer if necessary," wrote Jonah Bruno, a department spokesperson, in an email.

A city DOHMH spokesperson directed Gotham Gazette inquiries to Greater New York Hospital Association who "developed the system for assessing strain and triggers for EMS diversion, which just recently launched."

A spokesperson for GNYHA provided a planning document Monday detailing patient balance strategies, including an outline for redirecting admissions from surging hospitals, but it does not include concrete protocols or thresholds.

Criteria for designations within the three-tiered framework (normal level, elevated surge, and significant surge) are yet to be established, according to the outline, which was circulated to GNYHA member hospitals in late July.

"We're not quite there yet," said Jenna Mandel-Ricci, GNYHA's Vice President of Regulatory and Professional Affairs, and the network's lead on emergency preparedness, in a phone interview Tuesday. "We're making good progress."

GNYHA views itself more as a "thought leader" in surge management, providing insights and a new layer of data, which it hopes the New York City Fire Department will incorporate into its EMT algorithms.

"We're in very close contact with the fire department and we are kind of watching these next couple of weeks," Mandel-Ricci told Gotham Gazette.

"It's unclear if a real system for patient load has been implemented, or if it has, whether hospitals are actually keen to use it," said Rivera.

Rivera and others have pointed to two decades of hospital closures as contributing the imbalance of the spring apex. Since 2000, the state has lost roughly 20,000 hospital beds due to budget cuts.

"These hospital closures mostly occurred in poor neighborhoods where there were fewer patients who could pay -- not fewer patients, fewer patients who could pay -- so the inequities are clear when there are more beds per person in Manhattan than there are in Queens," Rivera said, adding, "these are also the neighborhoods where more patients are falling ill and dying from COVID-19."

According to Rivera, New York City's public hospitals received $106 million per hospital in federal CARES Act funding, while some private hospitals received four times that amount. The city's safety-net hospitals, where patients are treated regardless of insurance, are struggling to stay afloat as emergency visits have been down significantly since the spring.

FEMA continues to monitor the outbreak and healthcare systems and DOHMH is using federal aid "to improve information sharing and situational awareness of hospital capacity and throughput," according to Merlino.

Staffing

If covid levels reach heights from the spring, officials are worried there may not be enough health-care workers, including temporary personnel, to adequately staff surging facilities.

City health officials say they are working with the state to create a medical reserve corps of volunteers and have devised a procurement plan for emergency surge staffing. But the pool of additional workers eight months into the pandemic is limited, especially as so much of the rest of the country is dealing with spiking covid cases.

"The staffing concern is very real and I think everyone across the board will tell you that it's probably their biggest concern," said Mandel-Ricci of Greater New York Hospital Association.

A Memorandum of Agreement is available to contract personnel from the Department of Defense for private hospitals, according to DOHMH officials, but it is unclear if the federal government will make those resources available.

With covid outbreaks in many of the states where traveling nurses once hailed from, DOHMH and hospital administrators are looking to "cross-train" local non-ICU staff in intensive care, but nurses say the training is woefully lacking.

At Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, outpatient clinic nurses are getting online training modules and day of in-person orientation to the intensive care unit.

"These nurses have been out of the hospital for years, you can't expect them to know, to be competent, to adequately care for the patients when they haven't been in that setting," said Shamelee Morrison, who has been a medical/surgical nurse at Montefiore for 11 years. It can take two months to orient a nurse to a new unit, she told Gotham Gazette, "so you can't take these nurses and give them one day and say, 'OK, now go out and take care of these patients in a safe manner.' It's impossible. And that's what they're expecting the nurses to do."

One ICU nurse at NYU Langone Medical Center of Manhattan said it's like the city is already set up for an encore of thousands of nurses scrambling frantically in overwhelmed ICUs.

"I don't feel like I'm an experienced enough ICU nurse to be training anybody to be in the ICU," the Langone nurse told Gotham Gazette, speaking on the condition of anonymity. "And there's nurses who were only trained as ICU nurses during COVID, who are new grads, training new grads now for the second wave, which is absurd."

"The problem with the covid patients is that they're really, really sick and unstable," the nurse said. "They're not like light ICU patients, so to just go in that after a few weeks or like a month or two of being trained by an inexperienced nurse is really dangerous."

Morrison, from Montefiore, believes the hospital had more time to prepare staff for a potential second wave and dropped the ball. "I don't think they're doing much different. They're doing the bare minimum, if anything," she said by phone during a break in her shift. The New York State Nurses Association has delivered notice of a two-day strike at Montefiore's New Rochelle campus in an attempt to secure better staffing levels, wages and benefits.

With numbers rising throughout the city, hospitals are beginning to heighten protocols as staffing levels become an increasing concern. At NYU Langone, nurses are now being told to wear face shields over their masks, an additional precaution, even with patients who don't have covid. More nurses are getting sick, the Langone nurse said, with one floor having ten out.

The nurses Gotham Gazette spoke with said they don't get many details from their hospitals' administration about preparations for a second covid surge, outside of assurances that they have sufficient PPE supplies and indications that a second wave will not be as bad as a first -- both of which there is little proof of.

Supplies

Emergency regulations from the state Department of Health require all hospitals to have had a "90-day supply" of PPE by September 30. In April, Mayor de Blasio said the city would have its own 90-day stockpile, the NYC Strategic Reserve, in addition to the supplies held by individual hospitals. Representatives of the Mayor's Office and DOHMH have both said in separate statements that the Strategic Reserve will be completed "in the next few weeks," though neither office has said whether hospitals are on track to fulfill the state mandate or even whether the city is monitoring hospital supply levels. Guzman, the spokesperson for Health + Hospitals, said that the public hospital system had reached its 90-day goal.

"There are some hospitals that have not been able to achieve 90-days in all of the categories that are required," said Mandel-Ricci, of Greater New York Hospital Assocation. "But even in the categories where they haven't they're at like 70-days or 65-days, so they still have very large inventories," she added, noting, "some of these things are harder to get than others."

Mandel-Ricci pointed out that most hospitals in New York City are part of networks that can mobilize resources among their facilities.

Ventilators are more widely available than they were in March, when manufacturers couldn't make them fast enough to keep up with New York's most dire modeling.

Merlino, the DOHMH spokesperson, said hospitals were given the option to keep ventilators from national stockpiles and that the city now has "a large cache" for rapid deployment. When he announced the strategic reserve, de Blasio said the city would have a back-up supply of 4,000 ventilators but the administration has refused to say how many it now has.

Council Member Rivera said she has sought documentation on supplies and surge planning from city agencies and hospitals for months using her oversight powers as chair of the Council hospitals committee, without success.

"We have tried to get this information, not just from the Health + Hospital system, but also from the hospitals that are under that larger Greater New York Hospital Association umbrella," Rivera said.

"It's been incredibly frustrating," she added, "they just haven't provided those documents."

It remains unclear what the 90-day supply goal is based on. As Gotham Gazette recently reported, that number appears to be calibrated to PPE burn rates at the peak of the pandemic, when frontline healthcare workers were instructed to reuse equipment like facemasks far longer than what is traditionally advised. DOHMH and the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have both issued conservation guidance to be put in place to reduce severe shortages.

"We were told that Monte had a 90-day stockpile," Morrison said. "But then some of our nurses recently received an email stating that we were going to have to start recycling PPE."

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette

The Covid Crisis Made the New York Health Act More Urgent, More Unlikely, or Both

New Yorkers at a hospital, pre-pandemic (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

When Mariana Pineda was diagnosed with COVID-19 in April, she spent several days in the hospital being treated for pneumonia and sepsis after not being able to see a primary care doctor due to a recent change in insurance plans.

Pineda, an asthmatic, is one of an untold number of New Yorkers who put off seeking treatment for the coronavirus due to complications with insurance plans or not having health care coverage at all.

“The third day of feeling very sick at home I drove myself to urgent care because it felt like my lungs were filling with wet cement,” she said.

After her stay in the hospital and what seemed like a successful recovery, Pineda began to experience chest pain and difficulty breathing in August. A month later she underwent surgery for a pulmonary embolism and had to have six blood clots removed from her lungs.

Due to long-term complications from COVID-19, Pineda has been unable to work and was set to lose her employment-based insurance on October 19.

She was planning to enroll in COBRA, which will cost her thousands of dollars a month for coverage for herself and her four children, instead of the $400 she would usually pay monthly to get coverage through her job as a special education teacher.

“I'm not working and I don't have an income, there's no way I'm going to be able to afford the COBRA,” she said, “so I have to decide whether I just force myself to go back to work against doctor's orders to keep my health insurance.”

The pandemic has further exposed issues with how health insurance is so often tied to employment in the United States. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, almost 50% of New Yorkers got their health insurance via their jobs in 2019. Overall, the percentage of New Yorkers with health insurance was about 95% in 2019, a record high thanks to the state’s insurance marketplace and other factors.

But massive job loss has thrown health insurance coverage into question for many thousands of New Yorkers, and during a pandemic no less.

In New York City, the unemployment rate was only 3.4% in February, a record low for the city. However, coronavirus restrictions forced many businesses to close in March, tourism came to a halt, and unemployment numbers began to rise, peaking in June at 20.3%. The most recent numbers released by the Department of Labor show that the city unemployment rate was 13.2% in October. Unemployment has been marginally better statewide. Up from 3.7% in February, it peaked in July at 15.9% before coming back down to 9.6% in October.

For some, the link between getting health insurance through an employer and sudden job loss during a pandemic has highlighted the need for the passage of the New York Health Act, a bill in the state Legislature that would create a version of a single-payer healthcare system for universal health coverage in the state. The pandemic has dealt a significant blow to people who get their insurance from their jobs, leading proponents of the Health Act to call it more urgent than ever. As of September, the number of New Yorkers enrolled in Medicaid is up by over half a million from the same time last year.

For others, however, the legislation and what it portends is still too expensive and too disruptive, as it would completely change the way health insurance works in New York, and necessitate an overhaul of the tax code and a massive expansion of state government. Governor Andrew Cuomo, a third term Democrat, has long opposed passage of the New York Health Act on the grounds that it would be too expensive and disruptive, and while it passed the Democrat-controlled Assembly multiple times, the bill has not moved in the Assembly or Senate since Democrats took control of both chambers at the start of 2019. The bill’s future appears murky, and there is little indication that either majority plans to make it a top priority in 2021. The offices of Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins did not respond to requests for comment about the status of the New York Health Act in their respective chambers.

Under the Health Act, all residents of the state would be enrolled in a state-run insurance system for health care coverage, and one that would remove copays, concerns about finding “in-network” doctors, and other problems often associated with the current health insurance system. Proponents say that major inequalities in the current health insurance and health care systems that have been further exposed by the coronavirus pandemic would have been prevented or to a significant degree mitigated if single-payer health care had been in place in New York.

“If we had the New York Health Act sooner I would have had a primary care doctor all along,” said Pineda, who is working with the Campaign for New York Health to raise funds to cover the cost of her COBRA coverage and is a proponent of the legislation. “I probably would have gone to see him instead of trying to wait it out before I wound up, you know, with pneumonia and sepsis.”

The bill, the lead sponsors of which are State Senator Gustavo Rivera of the Bronx and Assemblymember Dick Gottfried of Manhattan, both Democrats, has passed the Assembly four times since 2015, but has not yet passed the Senate, and neither house has passed it since Democrats regained control of the State Senate in January 2019. Just before those elections, the Assembly passed the bill and all the Democratic members of the Senate signed on to Rivera’s bill as co-sponsors if they hadn’t already.

When both houses of the Legislature had majorities and began passing many progressive priorities, there was greater expectation among advocates and other supporters of the bill, including legislators who’ve sponsored it, that it would move. But given Cuomo’s long-standing opposition as well as questions about its feasibility and criticism from some labor unions, the legislative majorities put the bill on the back-burner while Rivera and Gottfried continued to discuss it with key stakeholders, especially the unions, and held a series of hearings on the bill while tinkering with its language, hoping for further discussion in 2020 and potential movement in 2021, after another state legislative election cycle that is unfolding this year.

Then the pandemic hit.

Assemblymember Gottfried believes that the New York Health Act would have helped prevent some of the now more than 26,000 deaths caused by the pandemic because New Yorkers would have had better, cheaper access to health care, both before and during the deadly outbreak.

“I believe a lot of people who developed COVID-19 symptoms put off going for care because they were afraid of the cost. And many of those people got a lot sicker, and many died as a result,” he said. Many New Yorkers who died, or got very ill, from COVID-19 also suffered from significant pre-existing conditions, like asthma and diabetes, that can develop or be worsened by insufficient medical care.

According to Gottfried, the bill is likely to have more support than ever in the upcoming session, beginning in January 2021, which he attributes to the pandemic and the new class of progressive Democrats taking office, some joining each of the Senate and Assembly. Several progressive candidates who beat Democratic incumbents in New York City or won open primaries in the city and elsewhere ran on the New York Health Act.

Senator Rivera, whose district has been among the hardest hit by the coronavirus in the five boroughs, says now is the time to get the legislation passed.

“We need to start going in that direction and do so aggressively,” he said. “If not, every time that we delay, it’s people that go broke because they get sick or die because they don't have care.”

The bill faces opposition from Republican legislators, who are not convinced that a single-payer health-care system would be something the state can successfully implement, as well as some moderate Democrats, labor unions, and others.

At a joint legislative hearing on the Health Act last year, Republican Senator Patrick Gallivan said a government-run, taxpayer-funded system was not the way to solve any issues within the current health-care system.

“This seems highly impractical in that no taxpayer-funded program can afford unlimited and unrestricted health care,” he said. “As I learned during a recent meeting with health-care experts in Toronto, approximately 30% of Canadian health care is funded by private insurance and out-of-pocket expenses.”

Bill Hammond, Senior Fellow for Health Policy at the Empire Center, a conservative think tank, said the legislation would be more disruptive than helpful, noting in an interview that 95% of New York’s population is already insured, and implementing the legislation would only disrupt their coverage. Hammond went on to say that the Health Act would consume the state Legislature “for the years that it takes to implement the plan, and probably forever after.”

Currently, the bill is in committee in both houses and the co-sponsors say there haven’t been any changes made to it as a result of the pandemic, though they had been making changes prior to the covid crisis based on the public hearings they held around the state last year.

In an interview on the Max & Murphy podcast earlier this year near the height of the pandemic in the city, Rivera emphasized the need for the New York Health Act and that it was imperative that the legislation gets passed as soon as possible.

“For those folks who would argue that it is complicated and is expensive: I would argue that it is neither as expensive or as complicated as the situation we find ourselves in right now,” he said.

The earliest the bill could pass is 2021, and only after significantly more debate, though that seems especially unlikely given the state’s ongoing public health, fiscal, and other crises wrought by the coronavirus outbreak. The influence of new, more progressive members in both Democratic conferences, including several backed by the New York City Democratic Socialists of America, could prove influential, but a path to passage is currently unclear. For something of this magnitude, a three-way deal with Governor Cuomo would also likely be a prerequisite to passage in the Legislature, and while Cuomo has come out in support of single-payer health care, he has said it should only be done at the federal level.

In August, Democratic State Senator Julia Salazar of Brooklyn, who is backed by the DSA, spoke about how the Legislature should be prioritizing the passage of the New York Health Act, particularly because of the impact the pandemic has had on communities of color.

“We really need to find a way to pass the New York Health Act or to ensure true universal health care,” she said on the Max & Murphy podcast. “A disproportionately high number of Black and brown New Yorkers are or have been dying from COVID-19 due to inequitable access and distribution of healthcare resources.”

Phara Souffrant Forrest, a nurse and Assemblymember-elect after winning this year’s election, in which she first triumphed in the primary over a Democratic incumbent in Brooklyn, has the passage of the New York Health Act at the top of her campaign platform. She said it was one reason she ran against Assemblymember Walter Mosley, echoing other challengers in recent years who’ve said that Democrats must really fight for the progressive policies they say they support.

During a late October interview on Max & Murphy, Souffrant, also a DSA member and endorsee, suggested that in order to repair the state’s budget and find the revenue to pay for the New York Health Act, the state needs to “instill justice into this budget where we have people paying their fair share.”

“We have 126 billionaires living in New York City that made billions during a pandemic. So money is being made. It's just people aren't getting any of it, and some people are getting all of it,” she said.

But both legislative majorities have a diversity of Democrats, and there are few beyond the furthest left candidates and incumbents who cite the Health Act as a top priority for the near future.

Gottfried said both he and Rivera are prepared to make the appropriate amendments in order to get the legislation passed and signed. What those amendments may be is not totally clear, however.

“It’s not really the state’s responsibility”

Whenever it is brought up, the New York Health Act faces scrutiny over the estimated cost of the program, though those concerns are heightened for some now that the state is facing large deficits given the massive drop in tax revenue due to the covid shutdown and resultant job losses and limited economic activity.

A 2018 assessment done by the RAND corporation has been the main source of information about the potential impacts of the New York Health Act. Overall, it showed that the state would need to collect massive additional amounts of tax revenue, but that that revenue would negate similar overall expenditures on health insurance and health care that New Yorkers currently pay. Depending on the tax structure involved, many New Yorkers would save money on health costs.

The study suggested that if the Health Act was soon passed, state government would be spending about the same amount of money in 2022 as it currently spends on health care and would only see significant savings in health care costs by 2031 -- a roughly 3% decrease in overall spending. The report went on to say that in 2022, the state would need to collect $139.1 billion in tax revenue to pay for the program, a 156% increase from what the state collected in tax revenue at the time. However, what the state collects in taxes for the program would replace what New York was spending on health care services, about $141 billion.

All New Yorkers enrolled in the state’s single-payer health care program would only pay the taxes taken out of their income -- every other cost associated with health insurance and care would be covered under the program. The Health Act is similar to how health insurance and care works in Canada and several other countries around the world, automatically providing residents access to both.

The proposed tax would be based on a person’s ability to pay -- anyone making less than $25,000 a year would be exempt. Rand’s 2018 assessment estimated that the new tax would range between 6.1% and 18.3%, depending on income, for everyone else.

However, under this model, Rand estimated that 98% of New Yorkers would end up paying less for their health care than they do now.

The state would require that all residents enroll in the program, which would essentially make private insurance in New York obsolete. This includes those enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid as well -- with permission from the federal government, the state would use the funds it receives from the federal government for those existing programs to pay for executing the new single-payer system. That would be in addition to a payroll tax, some of which would come out of workers’ paychecks and vary depending on how much money they make annually, with higher taxes on those making more income. Employers would pay at least 80% of the tax on payroll, and employees would pay up to 20%.

In order to use the funding the state gets for Medicaid and Medicare for implementing the New York Health Act, the state would need to receive a waiver from the federal government. Assemblymember Gottfried said New York may be able to get that waiver under a Democratic presidential administration, but that the state can proceed with creating a single-payer system if the legislation is passed.

“It is very clear that even without federal cooperation, a state can create a single-payer system without losing any of our current federal funding. Federal cooperation would make it simpler but is not really necessary, legally or financially,” Gottfried said, noting that a Biden administration may be more open to the idea of single-payer in New York, but did not elaborate on how the state would be able to implement the plan without a waiver.

One of the most prominent voices regularly arguing against the New York Health Act is Hammond, who says that the real issue is containing health care costs, which requires different answers. Hammond and other opponents of the legislation argue that the necessary taxes could discourage the wealthy from living in New York, and that the shifts involved would be incredibly disruptive to the way insurance and care work in the state.

“The majority of people have private coverage, it's not really the state's responsibility to take care of that,” Hammond said in an interview. “They're taking care of it on their own, either with their own money or their employer's money.”

Medicaid enrollment is up by about half a million people after the pandemic led to thousands of New Yorkers losing their jobs and their employment-provided insurance. To some, this means there are already systems in place to ensure people have access to insurance and care.

Hammond said there are more important things that state legislators should be focused on instead of creating a single-payer health-care system.

“We have a deficit of unprecedented proportions. We are right now thinking about major cuts to existing spending on schools, and transportation and health care,” he said.

The state budget deficit is estimated to be around $14.5 billion in the current fiscal year, which runs through March. Legislators and advocates have been pushing tax increases on top earners and the wealthy to plug that gap as well as to help fund the New York Health Act and other progressive priorities.

According to Lev Ginsburg, Senior Director of Government Affairs at the Business Council of New York State, introducing another income tax now could drive businesses and the wealthy out of New York.

“We already see a lot of problems in New York State with companies relocating out of the state or not coming to the state because of various expensive burdens,” he said. “We think that it would be a true economic disaster to put it in place now.”

Government Regulation, Health Care, and Labor Unions

Advocates for universal health insurance and care coverage in New York say that the system already in place for both private and state insurance plans is confusing and hard to navigate. They also point to the battles people must wage with their health insurance companies to get coverage for care.

Elisabeth Benjamin, Vice President of Health Initiatives at the Community Service Society, a nonprofit advocacy group focused on advancing opportunity for underserved communities, said that the current pricing system for hospitals is the biggest indicator of why the state needs a single-payer health system.

Hospitals charge a person depending on what insurance they have, rather than establishing a fixed set of prices for every service they offer. This can result in patients paying different amounts based on the type of insurance they have, and can discourage them from seeking care.

“If the hospitals charge the health plans more, the health plans can charge the consumer more, right? No one has an incentive, actually, to control costs,” she said.

Benjamin believes that there should be more government regulation on how much hospitals can charge patients, and said a single-payer health-care system can help achieve that. There are proposals to mandate uniform hospital and health care charges without moving to a single-payer insurance and care system.

A report done by the Campaign for New York Health, an organization advocating for universal health coverage for all New Yorkers, found that 50% of those surveyed said they were on private health insurance but couldn’t afford to use it because of copay costs. Katie Robbins, Director of the Campaign for New York Health, said that rising health-care costs likely contributed to the spread of coronavirus in New York.

“It would be really critical for a better response to this kind of pandemic to make sure that people have coverage as a guaranteed right and they don't delay because they're afraid of how much the treatment is going to cost,” she said.

The New York Health Act has garnered the support of several labor unions in New York, including the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA) and 1199 SEIU, a union for many health care and hospital workers. Both unions potentially see job security for their members in such a system.

Having health care off the bargaining table would allow the unions to negotiate better contracts for their members and potentially lead to a stronger union presence in New York, according to Judy Sheridan-González, the President of NYSNA.

“If unions seek out support for people, whether they're in their union or not, union density grows and union credibility is much more valued,” she said.

Sheridan-González said the passage of the New York Health Act could also lead to more job creation in the healthcare industry as a result of heightened demand for doctors.

“I certainly see it in primary care. I think that the initial phase-in, if people know that they don't have to pay anything, I think more people would access preventive care and primary care,” she said.

Not all unions are on board, however: the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT) has testified against the bill, most recently in 2019.

In a statement, NYSUT spokesperson Matthew Hamilton noted that the union supports efforts for universal health care, “especially during a public health crisis,” but that the union believes “a national health care system would be the most effective way to address this issue.”

***

by Caroline Leddy, Gotham Gazette

@caroline_leddy @GothamGazette

New York Leftists Strategize for the Post-Trump Era

State Senator Julia Salazar with activists (photo: NY Senate)

For four years, moderate and progressive Democrats, a number of independents, and even some Republicans have shared a common objective: ensure Donald Trump is a one-term president.

Now, with that objective accomplished and a moderate Democrat in Joe Biden set to enter the White House in January, leftists are ready to go all out, at the federal and local levels, to pull the party further leftward and accomplish goals like taxing the wealthy and defunding the police so that they can pass universal health care and increase funding for social programs including public education.

Those plans are also coming together in New York, where a new crop of left-wing Democrats was just elected to both houses of the state Legislature, building on a progressive slate that won State Senate seats in 2018, not to mention the ascension of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that year, followed by Rep.-elect Jamaal Bowman this year. Many of these winning candidates prevailed with the support of the New York City branch of the Democratic Socialists of America, the progressive Working Families Party, or both.

Along with impacting government policy at all levels, left-learning activists and elected officials now have their eyes on the 2021 New York City election cycle, which will see the election of a new mayor, as well as dozens of new City Council members, and other officials.

In an event that resembled a party as much as it did a strategizing session, state and city legislators, along with City Council candidates and progressive activists, met virtually on Tuesday night to chart a path for post-Trump leftism, with a focus on New York. They started by refuting claims by moderate Democrats, including Governor Andrew Cuomo, that a fear of socialism impeded Democratic successes in this year’s elections.

“It’s kind of nuts” that Democrats would say that, said Manhattan Assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou. “It’s no coincidence that all of The Squad won their reelection,” said Samuel Nemir-Olivares, the organizer and emcee of the event, who is also a district leader in Brooklyn. Nemir-Olivares echoed Ocasio-Cortez’s point that all swing-state House Democrats who endorsed Medicare for All won or were on track to win re-election.

Messaging by Republicans running for office also accused Democrats of being anti-police, and some Democrats took the bait, said State Senator Julia Salazar of Brooklyn, who was elected in 2018 over a more moderate Democratic incumbent with the support of the DSA. “Our movements for racial justice and economic justice cannot succeed if the Democratic Party insists on apologizing for them when elections come around,” she said. Significantly reducing funding for the police remains a large part of leftists’ platforms, especially considering the desperate financial situation the city and state governments are in. But some legislators in attendance said Democrats need to do a better job explaining what “defunding the police” means.

“You go into public housing saying defund NYPD, they’re gonna be like, ‘what the heck are you speaking about?’” said Jasmin Sanchez. “If we defund the police, this is what people in public housing and other minority communities are gonna think,” said Brooklyn Assemblymember Maritza Davila: “‘Who’s gonna protect us, and who’s gonna come out?’ So you have to spend more time explaining that.”

Brooklyn City Council candidate Wilfredo Florentino agreed, saying that community members don’t immediately embrace the thought of defunding the police and “what we really want to talk about is reinvesting in our community.”

“The reality is that progressive ideas are popular all across the country,” said Brooklyn Assemblymember-elect Emily Gallagher, who just defeated longtime liberal incumbent Joe Lentol in this year’s primary, “but we have to communicate them in a way that is user-friendly and is engaging.”

Even so, some activists used language that even many progressives shy away from. “We have to be extremely clear that we want to defund the police, that we want to abolish police,” said socialist activist Jawanza James Williams, expressing a different point of view from Democrats who are careful to draw a distinction between abolishing the police and diverting even large portions of police funding to social services. “Policing, including the NYPD itself, is a problematic institution that is predicated on the dehumanity of Black people,” Williams said.

CUNY student-activist Aaron Narraph Fernando shared a personal experience where public safety at his college asked for his identification and suggested he might pose a threat. “We need to really use [democratic socialist candidates] to defund and disband the NYPD,” he said.

Participants in the event expressed hope about the possibility of a supermajority of Democrats in the State Senate to match the one already in the Assembly, once officials finish counting absentee ballots. A few days later, leaders of the Senate Democrats gathered in Albany to celebrate the likely wins that would get them to that supermajority, and offer the ability for both houses to override vetoes by Governor Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat who is more moderate on many issues, especially related to the economy and taxes. But such overpowering of the governor would require progressive and moderate legislators to band together.

“While I’m very excited about a Democratic supermajority in the State Senate, I know that we’re still going to need to see that political courage,” said Salazar, “and we have not seen a great demonstration of political courage in the state Legislature collectively this year.”

A supermajority, leftists hope, would give state legislators power over a governor some think is too powerful and too centrist. “We have a top-heavy problem in New York,” said Zephyr Teachout, a progressive hero in New York who ran against Cuomo in the 2014 primary. “He’s really a Republican,” Manhattan City Council candidate Marti Gould Allen Cummings said of the third-term governor who is quite popular in New York City, especially among voters of color.

“Implementation is everything,” said Brooklyn City Council candidate Brandon West. “A lot of times, we’ve seen really good politics come together, progressive groups put a lot of energy in, and then everyone leaves after implementation, so no one focuses on it, so then it fails, then Cuomo’ll be like, ‘oh, that policy doesn’t work anymore — guess we shouldn’t have tried!’”

Gallagher said that if there is a supermajority, Democrats should take advantage of it to push through bold ideas. “These moments don’t last forever,” she said, “and if we don’t do anything with [the supermajority,] we will lose it.”

In order to accomplish controversial goals like defunding the police and decriminalizing sex work, Brooklyn City Council candidate Sandy Nurse said that progressives need to educate people to build community consensus. “We are literally just facilitating the needs and the wants of the people in our districts and in our communities,” she said. “If those priorities are not aligned, we’re not actually able to make those hard transformations that we’re asking for.”

One thing everyone seemed aligned on was higher taxes on the wealthy — something the governor has largely opposed, before and during the pandemic recession, opting instead for a combination of cuts, withholdings, and waiting for a federal aid package, hopefully a large one spurred by Biden’s victory.

“The money is there,” said Nemir-Olivares, pointing out that New York billionaires have only gotten richer during the pandemic. “The question is whether the political class and the governor has the will to really tax the multimillionaires and redistribute the wealth that we need and the workers themselves created so we can fund the actual health care that we need, the masks for the nurses, the tablets for our schools.”

“There are so many things that we can fund that aren’t police or jails,” Cummings said, citing the underway plan to build four new jails to replace those on Rikers Island. Those things, activists said, include making CUNY tuition-free again, forgiving all student debt, funding public housing, and fighting food insecurity. Other priorities include LGBTQ rights, the rights of undocumented people, canceling rent, legalizing marijuana use, and passing a Green New Deal to fight climate change.

“If we had invested in our communities, we wouldn’t have been hit that hard” by the pandemic and recession, said Niou. “If we had invested in our healthcare system, we wouldn’t have been hit that hard. If we had invested in our education system, we wouldn’t have been hit that hard. If we had invested in our small businesses, we wouldn’t have been hit that hard. This is the stuff that is so basic.”

***

by Lauren Hakimi, Gotham Gazette

@lauren_hakimi @GothamGazette

Democrats Hold Senate Majority, All of State Government; Here's What's on Their Agenda

Gov. Cuomo, Speaker Heastie, Majority Leader Stewart-Cousins (photo: Governor's Office)

Despite facing tough battles in districts that they narrowly won two years ago and being on the verge of defeat in some places, Democrats also flipped a few seats and will grow their large majority in the State Senate, retaining control of both chambers of the Legislature by wide margins. Along with the ongoing tenure of third-term Governor Andrew Cuomo, Democrats will keep full control of New York state government through 2022, the next state election year.

This means the party will have the opportunity, however dominated by the coronavirus public health and socioeconomic crises the state faces, to build on its long list of liberal legislative action from the 2019-2020 session, the first with full Democratic control of state government in a decade.

Though they appear set to continue intra-party bickering and more substantive debate between moderates and those further to the left, the continued dominance of state government may embolden Democrats to pursue additional legislative priorities. And a new crop of progressive legislators, some members of the Demcoratic Socialists of America, will join both the Assembly and Senate, with plans to pull those majorities further left.

But it’s uncertain what Democrats running state government will prioritize and what they will be able to accomplish as New York continues to face dire financial straits caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Perhaps now more than ever policy and finances are inextricably linked, though there are some measures with minimal fiscal impact that legislators are eyeing for next session.

Even with Democrat Joe Biden winning the presidency and the party holding on to the majority in the House of Representatives, the fate of the U.S. Senate lies in two January runoff elections in Georgia, leaving the prospects for major financial aid to New York in limbo.

Before Biden is sworn in as president on January 20, the Legislature will be scheduled to return to session and Cuomo scheduled to outline his own 2021 agenda and budget proposals for the next fiscal year. But prior to that, Cuomo and other state officials must deal with a current fiscal year budget crisis that they have yet to solve.

What that process entails is, along with the immense question of federal aid, one of a number of variables and connected crises that will determine what is top of mind for Democrats in early 2021.

The first priority for the governor and Legislature will be to stabilize the state’s finances. Cuomo, who received significantly expanded budget powers under emergency legislation passed during the early days of the coronavirus outbreak, has been holding back some local aid and other state spending, and putting off crucial larger decisions for months as he hopes for a next federal stimulus package. He has long-resisted calls, including from some legislators, to advance revenue-raising measures including tax hikes on the wealthy, holding out for more federal aid and saying he does not want to give top earners any more reason to leave New York for other states.

“We know the challenges facing our state, as we fight this pandemic and work to recover economically, are daunting," said Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, at a news conference on Monday. "As we continue to confront this crisis, we know that the burden must be shared fairly, and that we must secure additional revenues, including help from our federal government, and that all this must be done without relying on our working and middle class families, our struggling small businesses.”

She added, "Our priority right now, quite honestly, is to get out of this budget situation that we're in, to get people COVID-free to the extent that we can, to get this virus under control and to get the economic situation in our state under control."

There continues to be some slim hope for a lame-duck federal package before January 20, but Cuomo and others have expressed more optimism for what Biden may be able to negotiate once he takes power, whether with a split Congress or two Democratic chambers.

In an August 31 letter to Congress, Cuomo and labor leaders said the state needs at least $59 billion to cover the current fiscal year and next, a total covering state government, local governments, and state-affiliated authorities like the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which has been seeking its own $12 billion federal bailout.

“There is no combination of state efforts that will address this financial crisis without federal assistance,” they wrote. “Even if state and local governments cut expenses, increase taxes, and reduced services, the revenue shortfall would still be in the billions of dollars. Moreover, forcing state and local governments to take such actions would only further the pain and extend the period of time for the nation's economy to recover.”

Cuomo has withheld or held off on cutting tens of billions of dollars in local aid.

Many of the issues that Democrats in Albany confront will hinge on what any federal aid package looks like, and when it may come, if at all. For instance, a push for cancelling rent for thousands of New Yorkers to avoid an eviction crisis may fail without an infusion of funds. Any potential debate about providing universal health care in the state will likely be marginalized if the state is deeply in the hole. New taxes or increases in existing ones may be unnecessary if budget gaps are covered. "The reality is that we have a huge deficit and we need a lot of answers. And most of those good answers need to come from our federal government,” Stewart-Cousins said.

What also remains to be seen is how far left the new Democratic conferences in each chamber will swing. Several newly elected progressive Assembly members from New York City unseated long-term establishment Democrats in the primaries with support from the Working Families Party (WFP) and the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), among other left-wing groups. But that majority is quite large -- well over 100 out of 150 seats -- and while it is dominated by New York City members, Speaker Carl Heastie of the Bronx has always governed in a collaborative fashion with the more moderate Senate majority and Cuomo.

In the Senate, a mix of moderates and progressives will join or return to the conference, but Democrats may be emboldened by the fact that they passed many liberal priorities of the past two years and only added to their large majority. State Senator-elect Jabari Brisport of Brooklyn, an outspoken democratic socialist, is among those heading to Albany from the city who plan on pulling the Legislature to the left.

There are a slew of bills and policies, some revenue-related and others less so, some with more support from the leaders of the party and others pushed staunchly by the activist wing, that Democrats are poised to consider as the new Legislature is seated. Some have emerged as a consequence of the pandemic. Others have lingered from years past and from the previous session. Some were pushed hard by the insurgents who just won contested primaries, others were Cuomo’s priorities before the pandemic hit.

But because of the pandemic, taking stock of the election results and ascertaining any real 2021 “agenda” for Albany Democrats -- beyond salvaging the state’s finances and thus ensuring government programs happen, state government continues to function and local governments are funded -- is difficult. While there are important clues in the early, pre-pandemic 2020 agendas put forth by Cuomo and the legislative majorities, as well as policies promised by winning Democratic candidates, so much will indeed hinge on the state fiscal picture, what comes from Washington, D.C., and, potentially, where the debate over state tax policy lands.

Spokespeople for Governor Cuomo, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie did not respond to repeated requests for comment for this article.

While new items are likely to emerge or gain momentum, here’s a rundown of what Democrats may have on their 2021 state government agenda.

Marijuana Legalization

The legalization and taxation of marijuana for recreational use by adults has been a priority for Democrats for years, and Governor Cuomo has also embraced it in the last two budget sessions both as a criminal justice reform and a potential revenue-raiser that could eventually bring in more than $300 million for state coffers annually.

The governor and Democrat-led Legislature could not come to an agreement on legalization in either 2019 or 2020, though they did decriminalize possession to a degree earlier this year. The sticking point appears to be the amount of revenue that is re-invested in communities that have been most negatively impacted by marijuana criminalization and the larger “war on drugs.”

As neighboring states have moved towards legalization – New Jersey voters approved a ballot referendum on marijuana legalization on Tuesday – the governor has pursued the policy with more urgency as well and recently indicated it is something of a must for 2021. The issue will likely be a prominent agenda item in the upcoming legislative session, particularly as it could provide some help to fill the budget deficit the state faces, though mostly not until the industry is built out in future years.

Taxes

As the pandemic has devastated low-income New Yorkers and blown a hole in the state budget, there has been a growing clamor from left-wing Democrats and grassroots progressive activists to increase taxes on the wealthiest New Yorkers. Cuomo, however, has long been opposed to most new or increased taxes, and believes that such proposals would drive higher-income New Yorkers to migrate to states with lower tax rates.

Both the Senate and Assembly legislative leaders, Majority Leader Senator Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Speaker Carl Heastie, have expressed support for increasing taxes on millionaires and billionaires, but neither chamber nor the two in collaboration have moved to force the governor’s hand.

A newer class of progressive Democrats have also become a prominent bloc in the Senate and several of them have vowed to pursue new tax legislation rather than allow broad cuts to local aid and state services, as Cuomo has threatened to do. The incoming Assembly members who ran on progressive platforms to beat incumbents and other more moderate legislators have also vowed to pursue several revenue-raisers. While the Assembly Democrats have long advanced higher taxes on top earners, the Senate has joined Cuomo with more opposition. This summer, Stewart-Cousins announced a revenue working group, but it has not produced any recommendations.

Renter Protections and Homlessness Prevention

Millions of New Yorkers lost their jobs during the pandemic and though the governor placed temporary moratoriums on both residential and commercial rent evictions, hundreds of thousands of households and thousands of businesses are at risk of eviction as their rent piled up for months. Legislators and activists have been calling for a ‘cancellation’ of rents for those who’ve lost significant income and become unable to pay, but the state doesn’t have the fiscal ability to make landlords whole. Federal aid for this purpose would likely be necessary for the state to move ahead.

While much related to rent relief will depend on federal aid, there has been an ongoing call from some for a “good cause” eviction bill, which was not approved by the Legislature amid its passage of a massive package of rent protection in 2019, a package that mostly applied to those in rent-regulated apartments. The bill would give tenants of all kinds the right to renew a lease except in certain specific circumstances as well as restrict rent increases past a set threshold.

Meanwhile, Queens Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi’s proposed Home Stability Support legislation promises to be a strong deterrent against homelessness by increasing the value of rental vouchers for those on public assistance. But the bill has failed to move through the Legislature even in good fiscal times. Though it may be more necessary now than ever before, as more families are availing themselves of welfare benefits and a potential tsunami of evictions looms on the horizon, the state doesn’t have the cash flow to fund it without receiving significant federal assistance or significantly increasing taxes. Still, Hevesi and others are likely to continue pushing for the measure.

Voting and Election Reforms

With long lines during early voting and with the New York City Board of Elections making massive mistakes with absentee ballot mailings, the presidential election yet again prompted scrutiny of New York State’s election laws, which dictate the city BOE’s antiquated structure, and administrative procedures. Elected officials and advocates want to see changes to everything from voter registration to the structure of the BOE.

Though the Democrat-led Legislature has approved a slew of reforms to expand voting and improve election administration, there’s much left to be done. Among pending measures are same-day voter registration and no-excuse absentee ballots, both of which require amendments to the state constitution. The Legislature has already voted both proposals through and must pass them again before placing them on the ballot for voter approval.

New York is among the states that also takes the longest to count absentee ballots, with counting beginning a week after Election Day. State Senator Mike Gianaris has proposed legislation that would mandate that the count begins on election day.

Reforming the BOE is a harder task, requiring a state constitutional amendment as well. The agency is partisan by nature, with an equal number of commissioners appointed by Democrats and Republicans, the two parties receiving the largest number of votes in elections. Though it is the New York City BOE that has been the subject of most criticism, restructuring it would require state action and there are powerful establishment interests, particularly Heastie, the former head of the Bronx Democratic Party, who do not seem inclined to act.

Education Funding

In recent budget sessions, Governor Cuomo has attempted to change the way the state hands out Foundation Aid to struggling schools in less well-off districts, as required by the Campaign for Fiscal Equity state court decision in 2006. He proposed an “education equity” formula that would send more money to poorer schools by reallocating funds but not by significantly increasing foundation aid. While the proposal has some support from fiscal watchdogs, education advocates say it will underfund poorer schools in low-income communities of color.

Cuomo did not seem to push especially hard to implement the new formula this year. It remains to be seen if he will attempt to do so next year, even as he threatens to cut billions from local aid, including education.

Another Cuomo idea that failed last year was the expansion of eligibility for the state’s Excelsior Scholarship for tuition-free public college. The governor proposed increasing the income threshold from $125,000 in gross family income to $150,000. Without federal aid, there’s a chance that the program may in fact be cut next year.

Individual and Group Legal Protections

Last year, the governor sought to pass a bill that would close the so-called rape intoxication loophole, which makes it difficult to prosecute sexual assault when a victim is voluntarily intoxicated and cannot provide consent. But the measure was not approved in the state budget after the two legislative chambers failed to come to an agreement on the bill. The Senate and the governor’s office pledged to continue to advance it and could possibly take it up next year.

Governor Cuomo also proposed an expansive Equal Rights Amendment for the state, which would prevent discrimination by adding a list of protected categories to the state’s bill of rights including sex, ethnicity, national origin, age, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Though the Senate has approved a proposal similar to Cuomo’s, the Assembly has repeatedly passed a much narrower version. As with any amendment, it would need to pass the Legislature in two consecutive sessions before being placed on the ballot.

Gig Worker Protections

Last year, Cuomo promised to pursue protections for workers in the gig economy but failed to follow through, and he did not advance anything again this year. Over the years, lawmakers have proposed legislation but none has seen much movement.

Recent proposals have been based on the AB5 measure passed in California that created an “ABC test” for worker classification. That measure, which prevented misclassification of workers as independent contractors, experienced a major blow after California voters approved a ballot proposal, Proposition 22, in this year’s general election that rolled back some of the protections established under the law. Companies like Uber and Lyft bankrolled a $200 million campaign to promote the passage of that measure.

Criminal Justice Reform

Last year, the state Legislature approved a package of criminal justice reforms – including speedy trial, discovery, and bail reforms – that were broadly praised by progressives but faced opposition from some moderate Democrats, Republicans, and powerful law enforcement unions. Pieces of the reforms, notably on bail, were rolled back earlier this year, but the legislation was a major focus of Republicans in state legislative races, especially in Brooklyn, Long Island, and Hudson Valley swing districts. Yet Democrats appear to have prevailed in most of those races.