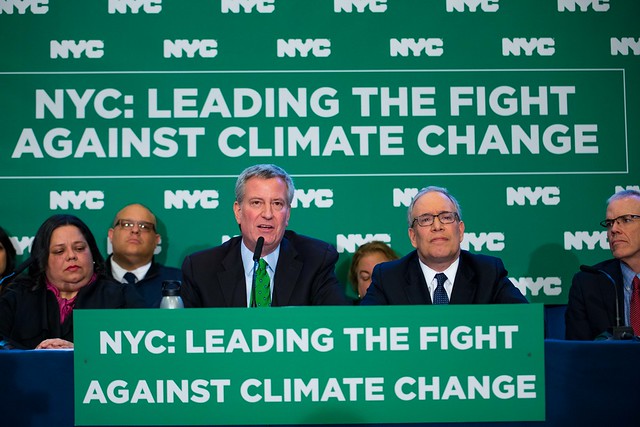

Mayor de Blasio & Comptroller Stringer (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayor's Office)

Amid the larger discussion about addressing climate change before it’s too late, debate is raging in New York over whether government-run and -affiliated pension funds worth hundreds of billions of dollars and responsible for payments that support hundreds of thousands of retirees should divest from fossil fuel company stock.

Advocates, elected officials, and others have been pushing at the city and state levels for full divestment so that the pension funds are not supporting or tied to companies that are leading contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, a warming planet, and the negative consequences of climate change.

But some officials have warned, and practiced, caution, putting forth arguments that the primary priority of pension fund investment must be return for current and future retirees, and that it is important not to overly politicize investment decisions, especially given how uncertain the future is and that some of the leading fossil fuel companies are at the front lines of figuring out the renewable energy future.

There’s also the argument, often made by State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, that by remaining invested with fossil fuel (and other) companies, it is possible as activist investors to help shift their behavior. And while New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer often espouses and practices that philosophy, when it comes to fossil fuel company divestment, Stringer has worked with Mayor Bill de Blasio, labor union leaders, and others to move city pension funds toward dropping stake in those companies.

The New York City and State pension fund pictures are significantly different, with responsibility at the state level much more concentrated in DiNapoli’s office than the city’s in Stringer’s. But the different approaches being taken by the two Democratic comptrollers, who are the popularly-elected chief fiscal officers of their respective jurisdictions, show divergent paths in this particularly fraught political, financial, environmental, and existential moment.

While he’s one of a number of key decision-makers, Stringer is pushing full speed ahead toward fossil fuel divestment by the city pension funds. DiNapoli, meanwhile, has cautioned against that approach, even criticizing it as overly political and reactionary, while taking his own steps to diversify investments, experiment with a carbon-free energy stock portfolio, and push fossil fuel companies toward new policies.

Advocacy groups like Fossil Free New York and New York Communities for Change are pushing for the $210-billion state pension fund, known as the Common Retirement Fund (CRF), to divest from fossil fuel companies completely. The CRF has about $13 billion in fossil fuel-related investments, according to Fossil Free New York.

In April 2018, as the Democratic primary in his bid for a third term was heating up, Governor Andrew Cuomo declared the state’s pension fund should divest from fossil fuels. But in New York the Governor does not control the pension fund; the State Comptroller is the sole fiduciary of the CRF and, as such, has final say over when investments are made and retracted.

While he took that stance, Cuomo has not made divestment a major focus, applying minimal pressure to DiNapoli to take more aggressive action. His office recently told Gotham Gazette that the governor is working with the DiNapoli on a path toward divestment, in large part through an advisory group they established together.

While he took that stance, Cuomo has not made divestment a major focus, applying minimal pressure to DiNapoli to take more aggressive action. His office recently told Gotham Gazette that the governor is working with the DiNapoli on a path toward divestment, in large part through an advisory group they established together.

Advocates did celebrate in March of this year when Cuomo took a significant new step, calling on state agencies and authorities such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) to examine divesting whatever funds they have in fossil fuel companies.

“As part of the Green New Deal, Governor Cuomo directed State authorities, public benefit corporations, and the State Insurance Fund, which collectively hold approximately $40 billion in investments, to study divesting from fossil fuels. They are reviewing and evaluating the feasibility and appropriateness of such a measure,” Jordan Levine, a spokesperson for Cuomo, said in a statement to Gotham Gazette.

The governor’s office was unable to identify at this time how much of that $40 billion is currently invested in fossil fuel companies.

Back in early 2017, DiNapoli and Stringer both argued that engaging with major fossil fuel producers like ExxonMobil as shareholders would yield better results than immediate divestments.

However, in 2017, Stringer and the five municipal pension funds initiated an analysis of their investments’ carbon footprint in 2017. Then, in January 2018, after the study concluded, Stringer changed his stance. He, Mayor de Blasio, and other pension fund board members announced their plan for three of the five pension funds (the police and firefighter pension funds are not currently part of the plan and account for less than a third of total pension assets). The city’s five funds have about $5 billion invested in fossil fuel producers out of almost $211 billion in pension fund investments.

In a celebratory announcement that month alongside de Blasio and others, Stringer asserted that he and other city pension fund trustees “would be shirking our fiduciary duty if we were not exploring all options to address climate risk.”

An involved divestment process is underway, at least at three of the funds -- the Comptroller and the Mayor have seats on the boards of all five pension funds but cannot make unilateral or even bilateral decisions about their investments.

State Response - DiNapoli and His Critics

Under considerable pressure to divest state pension funds from fossil fuel companies, in April 2018, Governor Cuomo and Comptroller DiNapoli convened the Decarbonization Advisory Panel to study the issue. In April of this year, the panel released its report, which made several recommendations and put forward “examples” of what the comptroller could do to mitigate the fund’s carbon footprint. However, the report was criticized by climate activists like 350.org’s Richard Brooks for not including a timeline or benchmarks to achieve divestment.

But even before the panel was assembled, DiNapoli had been taking steps around the question of divestment, creating a $10 billion portfolio of investments into green companies. “We’ve done a lot already to allocate money to climate solutions,” DiNapoli said during a May interview on The Capitol Pressroom with host Susan Arbetter, “they’d like to see us do even more there.”

But the comptroller’s stance has caught the ire of local climate activists, who are the ones who want him to “do even more,” as the comptroller put it. Pete Sikora, the climate and inequality campaigns director at New York Communities for Change, said the comptroller “continues to finance the climate crisis.”

“Not to be too sarcastic, but if you’re going to finance evil stuff that destroys our future, you'd hope the state would at least make - not lose - money off it,” Sikora said, noting that the energy sector “continues to trend down over a decade...of industry under-performance.”

“It’s simply insane to not divest, and losing money on the proposition makes it even more absurd,” said Sikora.

Despite growing pressure from activists and lawmakers on the issue, DiNapoli has maintained that his more moderate approach is what is in the best interest of the CRF and its members. He believes that implementing standards such as the ones suggested in the panel’s report will naturally lead to fossil fuel investments being phased out over time and would avoid the negative impacts of wholesale divestment.

In a June 2019 interview with WAMC’s Capitol Connection, DiNapoli said “when we make judgements about where to put the pension fund, we put it in the best interests of the state.” He went on to defend his approach in significantly more harsh terms than the mild-mannered and reserved DiNapoli typically uses.

Some state lawmakers disagree with the comptroller’s assessment and want to force the his hand on the issue.

The Fossil Fuel Divestment Act would require the CRF to withdraw all investments in the 200 largest fossil fuel companies. The FFDA sets a five-year deadline for this to happen and would allow the comptroller to stop or reverse divestment if it can be demonstrated that it would significantly hurt the CRF’s value.

Senator Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat and the FFDA’s prime sponsor in the state Senate, said in a statement that while the proposal did not pass during this year’s legislative session, she “continue[s] to have conversations with my colleagues about the importance of” the bill. She also added that she is “working on amending the bill based on testimony we heard, both to make it stronger and to address various concerns that were raised.”

“With all due respect to the Legislature, for the Legislature to start micromanaging the pension fund is a recipe for disaster long-term,” DiNapoli said on WAMC, adding that “it may be climate change today, but what will it be tomorrow?”

DiNapoli has previously divested the pension fund from gun companies following the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting and from the private prison industry over concerns about the treatment of immigrants and people of color in 2018. Both are cited by critics who want the comptroller to act more decisively on fossil fuel companies.

Krueger said she “strongly believe[s] that [DiNapoli] is wrong on divestment” when it comes to fossil fuels, while noting that they “have talked about divestment extensively” and the comptroller has “been a long-time champion of the environment and climate action.” Despite their talks, “neither of us have managed to convince the other,” she said.

Krueger criticized DiNapoli’s “strategy of engagement with major fossil fuel producers like ExxonMobil” for not “providing any consequences when they repeatedly brush him off. It’s time for some consequences.”

“New York should begin the process now or our retirees will be left holding the bag,” Krueger concluded.

“Does anybody think if we sell the stock tomorrow that’ll make the air cleaner? No,” DiNapoli said during the WAMC interview.

“Since it's become clear that Comptroller DiNapoli currently lacks the moral and fiduciary courage to stand up to the fossil fuel industry and Wall Street, this legislation is necessary,” said Sikora, referring to the Fossil Fuel Divestment Act, in an interview with Gotham Gazette.

“It’s clear we have our work cut out for ourselves in both houses,” said Sikora, assessing the bill’s likelihood of passage next session, which begins in January. During the last session, the FFDA had 28 sponsors in the 63-seat Senate and 37 in the 150-seat Assembly.

DiNapoli plans to follow the advisory panel’s recommendations. According to the DAP’s report called the Climate Action Plan, “rather than making a narrow recommendation to divest from specific stocks, the panel supports the concept of minimum standards to guide the fund in its decisions to sell securities and/or avoid investment managers whose operations and strategies are not sustainable.”

The report argues that divestment from unsustainable companies is “baked in” to this plan of action and that the fund will only invest in sustainable assets by 2030.

The panel’s report says that the CRF should have a minimum standard for where its funds are invested. The panel recommends that the criteria for these minimum standards be set through contracts, but only gave “examples” of what the standards could be, such as requiring “an appropriate corporate governance system for the management of climate-related issues” and “a lobbying policy actively supporting government actions to address climate change.”

The report also suggests examples of actions and timeline that the comptroller’s office could pursue, including “excluding all companies that derive more than 10% of revenue from mining thermal coal or account for more than 1% of global production” by 2020 and “if less than 5% decreased in [greenhouse gas] emissions year on year after” several engagements then “consider a shareholder resolution.”

When DiNapoli released the climate action plan, Fossil Free New York called it “a weak plan at a time when we need bold and transformative action,” and said it is “lip service and incrementalism.” The advocacy group further said “the plan includes no benchmarks, no firm delivery deadlines, no parameters to measure companies’ actions, and doesn’t even commit to divest from thermal coal companies, including ones on the edge of bankruptcy.” FFNY supports the Fossil Fuel Divestment Act.

On WCNY’s The Capitol Pressroom in May, DiNapoli said his opposition to divestment stemmed from his responsibility as fiduciary of the state’s pension fund, saying “this is my job, it’s what I was elected to do.”

He also brought up his 2018 reelection, in which he received more votes than he did in 2014, while Mark Dunlea, the Green Party candidate who campaigned almost exclusively on pension divestment from fossil fuel companies, did worse than the previous Green Party nominee when DiNapoli sought reelection in 2010.

“I actually feel that those in the broader public who’ve looked at this issue are more on our side,” the comptroller said. DiNapli’s Republican opponent in the race, Jonathan Trichter, criticized the comptroller from the right, saying he was playing politics by making the moves he had to explore divestment and create the Sustainable Investment Program, in which $10 billion of pension assets are invested in low-emissions or green companies.

Ceres, a sustainability nonprofit, praises Comptroller DiNapoli as “a global leader in the fight against climate change, addressing material risks and pursuing opportunities for the Fund’s investments.” Ceres supports the “active” investor strategy that DiNapoli has claimed is a better path forward than divestment.

During a debate last fall, Dunlea claimed “if we divested a decade ago, we’d have about $22 billion in the state pension fund,” referring to a 2018 assement from Corporate Knights. A competing unions-funded study said the opposite.

While there are competing studies, Bloomberg News reported recently that some private investment funds are beginning to divest themselves from fossil fuel producers, based solely on the financial risks involved.

DiNapoli regularly notes that while he is the sole fiduciary, he does not make his decisions alone by a long shot, with a chief investment officer, a board of advisors, and others who help determine all aspects of pension fund management. On The Capitol Pressroom, DiNapoli said he was unfairly being singled out by activists and other critics, while also noting that New York City was still in the study phase and that two of the five city pension funds had not agreed to divest.

“So the pressure on me is that we guarantee retirement security for the 1.1 million members of the pension plan, which is a lot of pressure,” DiNapoli said.

New York City Divestment

City Comptroller Scott Stringer has changed course from his previous stance and is now leading an initiative to divest the city’s pension funds from fossil fuel companies, although he is encountering his own challenges in doing so.

“New York City is planting the seed for a clean, green, and thriving economy that can truly support future generations,” Stringer said in a statement to Gotham Gazette. The city has “taken this first-in-the-nation step toward divestment to protect both the retirement security of our city’s workers and the future of our planet,” the comptroller added.

The plan announced by Stringer and Mayor de Blasio in January 2018 set a goal of total divestment within five years. As of July 2019, the city is still in the planning stages, having sent out a request for proposals (RFP) for financial advisors to come up with a divestment strategy last December. The comptroller will select a plan to move forward by December 1 of this yea. But, a key wrinkle in the process is that two of the city’s five municipal pension funds are not on board with divestment as of now.

Unlike the state pension fund, New York City’s public employee pensions are not unified under one system. Instead, there are five separate funds, each with their own boards. In total, the pension funds account for over $195 billion in assets. The largest is the New York City Employees Retirement System (NYCERS), which handles the pensions for most municipal employees.

There were two pension funds for the city’s education-related employees, the Board of Education Retirement System (BERS) covers most non-teacher civil service employees of the city’s school district, while the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) is for educators employed by the Department of Education, CUNY, or charter schools in the city. The NYPD and FDNY each have their own pension funds, the Police Pension Fund (PPF) and Fire Department Pension Fund (FDPF), respectively.

Also unlike the state pension fund, each of the five funds has its own board and the city comptroller is not the sole fiduciary of the funds. Each board has its own composition requirements. The Mayor or a mayoral appointee sits on all five boards, as does the city comptroller. The Public Advocate sits on the NYCERS board. Also, relevant city officials sit on some of the boards, such as the Police Commissioner on the PPF board and the schools chancellor on the BERS board.

The NYCERS board includes a mayoral appointee, the comptroller, the Public Advocate, and the five borough presidents, along with representatives from labor unions including AFSCME, the Teamsters, and the Transport Workers Union, which are the three unions with the most members in the fund.

Primarily, pension fund board members are representatives of pension-eligible employees. Eight of the twelve board members for the both the PPF and the FDPF are either union leaders or elected representatives of pension fund members.

In 2017, all five pension funds initiated a study of climate change’s effects on their funds, which was led by the comptroller’s office. However, a year later, the police and firefighter pension funds did not join the other three funds in announcing plans to divest from fossil fuels.

The PPF and FDPF’s bylaws both require a seven-twelfths majority of the board to take action on anything, such as a divestment proposal. The comptroller and mayoral appointees on both boards fall far short of having the votes to divest without buy-in from at least some of the union leaders or employees.

In a statement, Sikora praised the comptroller, along with Mayor de Blaiso and other trustees, for “taking real action to fight the climate crisis and we look forward to complete divestment.” Sikora also said that New York Communities for Change is “satisfied with the progress to date” of the city’s divestment plan.

The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association and the Uniformed Firefighters Association did not respond to repeated requests for comment regarding their positions on the city divestment plan.

***

by Andrew Millman, Gotham Gazette

@millman_andrew @GothamGazette

Ben Max contributed to this article.