It’s Time for a Really Robust Ranked-Choice Voting Education Effort

Voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Voting is the backbone of our democracy, and should reflect the will of the people. That is the idea behind New York City’s 2019 vote, in which 73% of voters supported a ballot question changing our electoral process from a single choice plurality voting to a new system, known as ranked-choice voting (RCV). Following the lead of cities like Minneapolis and San Francisco, voters decided it was time to change the way we select the leaders in our local government.

In party primary and special elections for city government positions, RCV allows voters to rank up to five candidates by order of preference. If no candidate receives a majority of first-place votes, the candidate in last place is eliminated and that candidate’s votes are redistributed based on those voters’ second choices. The process continues until a candidate receives an outright majority.

According to proponents of the new system, there are many benefits, including ensuring that winners have broader support, discouraging negative campaigning, and avoiding costly run-off elections. But in addition to reflecting the will of the people, it must also be easy and accessible, and there are strong concerns about the timing of implementation and the ability of our New York City Campaign Finance Board (CFB) to properly inform voters of this new change to how they will be electing their representatives.

In the first special election this year, in Queens’ City Council District 24, a candidate received a majority of first-place votes, negating the opportunity to see ranked-choice voting in action. When I speak to voters about the upcoming City Council special election here in the Northwest Bronx, in which I am running, it is clear that many do not know about the shift to ranked-choice voting, and even those who vote in every election are unfamiliar with the concept. This is deeply concerning, as the democratic promise of RCV relies on an informed and educated electorate.

But due to a lack of outreach and education on the part of the CFB, which is tasked with those responsibilities by the RCV law, it is likely that voters may end up selecting their top choice while leaving other choices blank, which could effectively disenfranchise those voters and leave them without the voice they were promised when these reforms were made. This is not the intention of these reforms, and if we want to fully embrace the new system, widespread education must be implemented by the CFB. Even worse, voters may end up invalidating their ballots due to errors. I was very troubled to learn that while there are opportunities for those voting in person to fix ballot errors, there is no ballot curing process for voters who vote by mail and vote for more than one candidate in the same ranking, or “over-vote” — a mistake that we can predict and address if we take action now.

As New Yorkers, we like to think that our city government reflects our progressive values. However, the most vulnerable residents in our city have always been left behind, and we often fail to get resources to those who need it the most. We saw this happen in last year’s elections, where problems with absentee ballots disproportionately negatively impacted seniors and people with disabilities, and in the middle of a pandemic forced voters to choose between their health and casting their vote. Without proper education, the new ranked-choice voting system has the potential to disenfranchise voters who are historically overlooked, including immigrants, people of color, and older adults.

The CFB’s actions to reach voters are insufficient. It is currently hosting RCV education webinars, but they are not widely publicized or advertised to the general public. To try to supplement these, the CFB has also enlisted community groups to conduct RCV workshops for voters. This means that a voter’s opportunity to learn about the new system can depend on the enterprise of their local community organizations, and whether or not residents are plugged in to those organizations. We are already seeing more of these workshops taking place in white, affluent parts of our city, often for younger or more technologically-adept individuals. The pandemic has shone a light on the digital divide that affects our communities with inadequate access to the internet, which is crucial to attending these trainings amid a pandemic. Furthermore, there appears to be little effort to target non-English speakers, making language access yet another barrier for RCV education.

I am dismayed by the thought of voters being confused while they fill out their ballots. The CFB must increase its efforts to run a robust public education campaign immediately. Our city must immediately expand community outreach, and provide education on TV, digital platforms, and radio. RCV information should already be posted on the almost 2,000 LinkNYC kiosks across the city. We should also advertise on our subways platforms and bus stops. We should incorporate RCV education into social services, such as meal delivery to seniors. This education campaign must extend to every neighborhood in our city, with dedicated resources for inclusive language access.

I have fought to expand access to early voting and mail-in balloting, and to make the process of voting easier and accessible for all New Yorkers, including non-English speakers and people with disabilities. The rollout of RCV still leaves many questions unanswered, which threatens to disenfranchise wide groups of voters. Our seniors, who have been voting the same way their entire lives, now must contend with this new system without sufficient education. It is not beyond the capability of the CFB to do this right. If we don’t get serious about ranked-choice voting education for our city’s voters, the very communities that need the most support during this pandemic will once again be voiceless.

***

Eric Dinowitz is a candidate for City Council in the District 11 special election taking place on March 23 in the Bronx. On Twitter @EricDinowitz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

At-Risk Communities Need a Covid Hero to Protect Critical Federal Resources

Gov. Cuomo (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

Governor Cuomo has worked hard to cultivate a national reputation as the Emmy Award-winning hero of his own covid reality show – so why is he stripping federal resources from hospitals, clinics, and health centers on the front lines of the crisis?

Last year, the Cuomo Administration included a provision in the state budget that would cost safety net providers an estimated $154 million in federal resources the first year and $1.5 billion over five years. This Albany accounting gimmick, set to take effect on April 1, would “carve out” the state’s Medicaid pharmacy benefit. The problem is that this “carve out” results in the state rejecting federal resources provided by the 340B drug discount program. This program makes it possible for health care providers to serve New York’s most vulnerable communities.

Fortunately, there’s a legislative fix that will buy time for a long-term solution. A bill sponsored by Assembly Health Committee Chair Richard Gottfried (A. 1671) would delay implementation of this “carve out” for three years, giving us time to work with the Governor, Legislature, and fellow stakeholders to ensure that the state doesn’t give up federal resources for vulnerable New Yorkers just to fill a budget shortfall.

As pharmacists in organizations that receive federal support under the Ryan White Care Act, we are on the frontlines in caring for patients with HIV/AIDS and vaccinating thousands of New Yorkers every week against COVID-19. To understand how devastating these cuts are, you have to understand the communities we serve. Half of all Americans living with HIV/AIDS receive medical care from a Ryan White clinic. Our patients are 70% Black or Hispanic, a majority are LGBTQ, 61% live at or below the poverty line, and 62% are experiencing homelessness or need housing assistance.

Our patients have been hit hardest by the pandemic and there remains great mistrust in the health care system from historical wrongs perpetrated against communities of color. Just last week, the Governor traveled to a public housing residence in Brooklyn to call attention to this crisis within a crisis – with Black and Latino Americans 2.8 times more likely than whites to die from COVID-19.

We work every day to build trust with our patients in these hardest hit communities, and now we’re the ones working to build trust in the vaccine. We are the ones responsible for getting that vaccine into arms – twice – so why would the Governor divert critical funding from that effort?

While the Governor often speaks about vulnerable communities, his own budget is attacking a proven and effective weapon against covid – the 340B drug discount program. The resources 340B brings to safety net providers allows us to engage these most at-risk communities. It provides resources for physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and outreach staff. It supports vaccine clinics where we manage check-in, patient flow, post-vaccine observation, and data transmission to the state. And it allows us to provide transportation to bring patients to the vaccine or the vaccine to patients.

Community health centers reeling from the pandemic have already had to deal with the state withholding funds. Now, on top of that, the state is removing what for many is our largest resource – the discount from the federal 340B drug pricing program. Undermining this resource will make it impossible for health centers to reach the communities that Albany and Washington so desperately want and need us to reach.

New York State’s most vulnerable communities need more than an Emmy-award winning TV show. We need a real covid hero.

***

Mark Malahosky is Vice President of Pharmacy Services for Trillium Health. Dr. Patrick Hildenbrandt is Chief Pharmacy Officer at Evergreen Health Services.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Make No Mistake: The Job of the District Attorney is to Fight Crime

Liz Crotty (photo: Liz Crotty for DA)

In this race for Manhattan District Attorney, candidates will talk your ear off criticizing the current occupant of the office, and cataloging all the things wrong with prosecutions. While there are a great deal of legitimate criticisms, nevertheless one might be left scratching their head to understand what candidates actually plan to do as DA. That is why candidates must outline not only what the next DA must stop doing, but also what she should do.

So what should the Manhattan District Attorney do? First and foremost, she must seek justice for all and protect and support crime victims and witnesses. The DA’s office should investigate and prosecute criminal activity in Manhattan, both on its own and with the NYPD and other law enforcement agencies, in order to save lives and keep every neighborhood in the borough safe for those who live, work, and visit here.

The DA should use every available legal resource to ensure prosecutions are based on credible, reliable, and admissible evidence, and proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Prosecutions should not be based on the defendant’s celebrity status, the publicity the case would generate, or the prosecutor’s personal empathy with the victim. Besides fairly prosecuting the guilty, the DA should also protect the innocent. The office should look at each case individually when deciding whether to pursue a criminal prosecution, dismiss a case, or divert to drug treatment or another program, using its prosecutorial discretion wisely, thoughtfully, and appropriately.

The District Attorney should continue to use a vertical prosecution system. This means that, with very few exceptions, each felony case is assigned to one Assistant District Attorney, who stays with the case from the time it is first written up until the time the case is resolved. That ensures case continuity for victims and witnesses, which is the best approach for prosecution.

The DA should seek bail selectively, following the factors enumerated in section 510 of the New York Criminal Procedure Law. The DA should protect defendants’ rights to presumption of innocence, a speedy trial, and detention only after due process. Forcing defendants to spend weeks, months, or even years in pretrial detention, or the threat thereof, should not be a tool to coerce people into accepting plea deals.

The DA should examine all the facts and underlying circumstances of a case before deciding whether a plea offer is a fair, just, and appropriate resolution of the case. The offer should not become less favorable the more time passes, as “punishment” for the defendant not accepting a deal earlier. And she should lobby Albany not to enact lengthy mandatory minimum sentences that compel defendants to plead guilty to avoid the prospect of spending decades in prison.

The DA should present cases to a grand jury only after a thorough investigation and a review of all available evidence. She should not manipulate the proceedings to “indict a ham sandwich” or not indict someone as a personal favor. Nor should she present cases only because doing so is popular with the public.

The District Attorney should always protect the right to a fair trial. She should expeditiously provide the defendant with the full body of evidence, including any that may be exonerating. She should ensure that the jury is impartial, and not chosen because they are conducive to finding someone guilty. And she must realize that some law enforcement officers are not credible, and inform the defense of this should any such officer testify.

The DA should make every effort to accommodate the schedules of all witnesses.

The DA should seek fair, just, and appropriate sentences in all cases, including non-jail sentences. And the DA should consider, when fair, just, and appropriate, “re-pleader” offers, wherein a defendant is permitted to plead guilty with specified conditions, such as restorative justice, community service, and/or treatment programs, and if a defendant avoids re-arrest and successfully completes the conditions of the plea, a defendant may then withdraw the plea and earn a conviction to a lesser offense, or even a violation or outright dismissal.

The DA should consider, when fair, just, and appropriate, and after consulting with the victim, offering restorative justice programs to all eligible defendants who demonstrate a willingness to learn from past mistakes.

The District Attorney should always scrupulously avoid activities that pose a conflict of interest. She should not give special treatment to defendants or defense attorneys who have given donations to the DA and other elected officials. The DA also should not accept donations from unions representing law enforcement officers, because she may have to investigate those officers accused of misconduct.

The DA should endeavor to hire attorneys and support staff who are as diverse as the borough of Manhattan, and who are caring, fair, smart, have common sense, and are dedicated to serving the public. They should live in New York. And the DA should require her attorneys to participate in mandatory training programs that teach best practices and ethics.

Finally, the District Attorney should regularly conduct community-based events and presentations in schools. Manhattan’s communities, including those that have received the least fair treatment from the criminal justice system, should have faith in the office, and the DA must do her part to cultivate it.

We cannot fall into the trap of believing there is a choice between safety and civil rights, but we must be honest about our legally feasible paths to achieving both.

The responsibilities of the District Attorney differ from those of the mayor, a legislator, or the police commissioner. When criminal justice reforms are sold to the public by candidates who will never be able to carry them out it equates to campaign smoke and mirrors, which ultimately leaves voters feeling frustrated and disgruntled election cycle after election cycle.

The most important reforms the District Attorney can enact must come from within the confines of her mandated responsibilities and discretionary latitude. To claim that the DA can formulate and institute public policy is fallacious. That is the job of our state and city lawmakers.

The next Manhattan District Attorney, whoever she is, must have a proactive vision for her tenure, and find real, workable solutions within the purview of the job. She cannot merely enumerate grievances with the current office and the criminal justice system. Because the District Attorney is a leader, not a critic.

***

Liz Crotty is a Democratic candidate for Manhattan District Attorney. On Twitter @LizCrotty2021.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Latinos and the 2021 New York City Mayoral Election

At the Puerto Rican Day Parade (photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

Will Latinos finally help elect the first Latino mayor in New York City history? With a term-limited Bill de Blasio, and with Latinos a growing political force in Gotham, two Latino candidates on the Democratic side are vying to replace him in Gracie Mansion and Fernando Mateo has just announced his candidacy to gain the Republican nomination.

Brooklyn City Council Member Carlos Menchaca and long-time nonprofit executive Dianne Morales have positioned themselves within the progressive wing of the Democratic Party as they seek the city’s top job. Both come to this mayoral race with considerably less name recognition than two previous top-tier Latino candidates that sought the mayoralty, Herman Badillo and Fernando Ferrer.

Badillo, the first Latino to run competitively for mayor, initiated his quest for the seat in 1969, having served as Bronx Borough President for the previous three years. Badillo also gained some notoriety as a commissioner in the John Lindsey mayoral administration.

Ferrer, who also served as Bronx Borough President and as a City Council member before that, sought the mayoralty in 2001 and again in 2005. Badillo never did secure the Democratic nomination (nor the Republican one in 2001). Ferrer did—but subsequently lost to then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg in the 2005 general election.

The context in which Menchaca and Morales find themselves is vastly different from that of Badillo and Ferrer. For one, the Latino base is much more diverse in its ethnic and cultural makeup. For another, the internal dynamics of the Democratic Party seem to be shifting from racial and ethnic identity politics to ideological positioning.

Regarding the diversity found in Latino communities in New York, we see that Puerto Ricans, historically the largest Latino group in New York, are no longer the only ones representing Latinos. Today, New York City has a large number of Dominican, Colombian, Ecuadorian, and Peruvian elected officials. The Bronx, once a hub of Puerto Rican presence, now has the largest Dominican community in the city, and Queens is a hub for Ecuadorians and Colombians. Brooklyn also exemplifies the diversity of the Latino community, including the presence of a significant cluster of Mexican hermanos and hermanas in Sunset Park, for instance, which is part of the district represented by Menchaca, who is Mexican-American. Morales is of Puerto Rican descent.

The diversity among Latinos in New York is worth celebrating. But will this diverse Latino community vote as a bloc and become the power base that it can be? Will New York City elect its first Latino mayor?

Comprising a quarter of the Democratic primary electorate, Latinos are a force to be reckoned with. But by itself the Latino vote is insufficient to elect a candidate, even if the candidate is a Latino. To win, the candidate will need to build coalitions across ideological, geographical, and ethnic differences. The one Latino candidate that was seen as having a viable path from Grand Concourse to Gracie Mansion was Ruben Diaz, Jr. With a sizable campaign warchest and some name recognition as Bronx Borough President, Diaz Jr. would have surely positioned himself among the top-tier candidates on the Democratic side, but he decided not to run.

For the two Democratic Latino contenders this year, forming such a coalition will be difficult, even with the new ranked-choice voting system. Morales and Menchaca remain largely unknown entities at a citywide level. And both candidates, especially Menchaca, lag behind in fundraising and have not received the public matching funds that could give their campaigns new life (Morales says she will hit the requisite threshold at the next filing in March).

Largely because Republicans are vastly outnumbered in New York City, Mateo would have practically no chance of winning the mayoralty, even if he were to win the Republican primary.

Despite challenges, Morales has proven to be a formidable candidate, developing fascinating policy proposals that will appeal to many primary voters. Unfortunately, this may not be enough. But if that’s the case, Morales’ efforts will nonetheless likely help forge a path for her to run for elected office again in the future.

Based on the current crop of Latino candidates and the current dynamics in the mayoral race, Latinos will likely have to wait longer for one of their own to finally become mayor of Gotham City. But with a sufficiently strong voting electoral presence in June, Latinos can again demonstrate that they are a force to be taken seriously and a growing base upon which to win a mayoral race.

***

Eli Valentin is a political analyst and author of the forthcoming book, Reinhold Niebur: A Political Life. On Twitter @EliValentinNYPA.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Imagining a DeCentral Park

Bikers in Central Park (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The past year has taught us all just how valuable outdoor space truly is, and how much our current cityscape is sorely lacking. Nearly 20% of New Yorkers, almost 1.5 million people, are not within walking distance of a park. But there is a solution right before our eyes, a hidden “Decentral Park” in our city’s streets.

Open Streets, Open Restaurants, and pop-up bike lanes have turned our conception of how we can and should use our streetscape on its head. As our street grid makes up 27% of the land in New York City, it’s about time that we look for ways to use those precious square feet to give the most benefit to the most people. By reclaiming just a fraction of our on-street parking spaces to make pocket parks, we can transform our curbs from unsightly storage into much-needed community hubs and green space.

Although the city is currently home to more than 2,300 parks, they are unevenly distributed. Lower income areas and communities of color, neighborhoods like the South Bronx, Jackson Heights, and Crown Heights, are among those with the least amount of land devoted to public space. Affluent, and often whiter, neighborhoods have not only greater access to parks, but also more park space in total: according to the Trust for Public Land, average park size in wealthy neighborhoods is 14 acres, while in poor neighborhoods it is just 6.4 acres.

We all benefit from parks, and a decentralized network of small parks throughout the five boroughs will help level this playing field – literally. While marquee greenspaces like Central Park or Flushing Meadows-Corona Park offer flagship destinations for New Yorkers and visitors alike, the power of small parks is underrated. Research shows that exposure to even small amounts of green space and nature can reduce stress, and that access to communal space helps build interpersonal relations and supportive social networks. Providing parks within access of every New Yorker will make us a healthier and happier city.

There are 3 million on-street parking spaces in New York City. By exchanging just 10% of these parking spaces for pocket parks, we can immediately create universal park access. The city’s current definition of a parallel parking spot is 8.5 feet deep by 24 feet long – which means that in each spot, there is over 200 square feet of potential public space right in front of us. That alone is bigger than some of our apartments, but together it could amount to over 1,300 acres of public space, more than one-and-a-half Central Parks in our citywide DeCentral Park.

Pocket parks can take a variety of forms, and we have to look no further than the existing Street Seats program as a starting point for potential designs. Different models can include tables, chairs, and benches, others can include more active play equipment, and still more could be home to community gardens or other greenery. These parks can and should be as varied and diverse as our communities themselves, and implementation must include community visioning to ensure that they are empowering spaces, not imposing ones.

You would be hard-pressed to find a more heated point of contention in New York than parking, and challenging the status quo will not be easy. But in this debate, we can actually look to one of history’s biggest proponents of urban automobiles for guidance. New York’s most complicated character, Robert Moses, despite all his many faults, shrewdly understood the importance of parks, famously noting “as long as you're on the side of the parks, you're on the side of the angels; you can't lose.” Indeed, a recent Transportation Alternatives survey found that 84% of New Yorkers support more space for children to play, and 83% support more trees and greenery, even if either would mean less parking.

Ironically, Moses’ work of slicing and dicing our city over the 20th century has left us with a built environment where the predominant urban feature is parking, not parks. But the point behind this message is to think about what we gain, not what we lose. In the next decade, as autonomous vehicles begin to rise and as reforms like residential parking permits and congestion pricing take shape, we’ll ultimately see a decreasing demand for private car storage. How we reclaim and make use of our public space will be the defining issue of our city’s next chapter – and starting with parks means that we’re starting off on the right foot.

***

Ben Guttmann is a former candidate for City Council, member of Queens Community Board 2, co-founder of marketing agency Digital Natives Group, and adjunct lecturer at Baruch College. Twitter: @guttmann.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This Year’s Mayoral Campaign Can Contribute to a Healthier, More Equitable Food System for New York City

Healthy food help (photo: Jeff Reed/City Council)

On February 9, nine of the more than 30 candidates for New York City Mayor participated in the Mayoral Food Forum 2021, a discussion of the future of food policy in the city. Candidates who joined the event included Eric Adams, Shaun Donovan, Kathryn Garcia, Ray McGuire, Dianne Morales, Scott Stringer, Jocelyn Taylor, and Maya Wiley. Eleven New York City food organizations*, including the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, which I direct, sponsored the event. More than a thousand people used Zoom to watch the lively and spirited discussion, moderated by Errol Louis of NY1. Questions addressed food insecurity, low wage labor, urban agriculture, school food, and other topics.

I had also served as one of the organizers of the previous Mayoral Forum on Food Policy on July 17, 2013, during the last “open” mayoral race. That one, moderated by New York University nutritionist Marion Nestle, had featured candidates Sal Albanese, Bill de Blasio, John Catsimatidis, Christine Quinn, and Anthony Weiner. Again more than a thousand people participated—in person in those pre-pandemic days—and 76 organizations sponsored the event.

Reflecting on these two experiences eight years apart led me to ask how food policy and the food movement have changed in the last eight years and what these changes hold for the future of food policy in our city. Some advances were obvious. This year’s crop of mayoral candidates seemed more knowledgeable on food policy than the 2013 field. They spoke proficiently about SNAP enrollment, school food, the use of eminent domain to expand urban farms, and the need for more staff for the Mayor’s Office of Food Policy. All agreed that shaping food policy was an important mayoral responsibility and that using municipal authority to make the city’s food system more equitable should be a priority.

What explains their greater sophistication? First, it reflects the success of food activists in the last decade. Food and social justice activists have won free school lunch for all city school children, new policies to protect urban gardens and farms, eased rules for enrolling in SNAP, more attention to city procurement of school and other institutional food, and higher wages for food workers. The ongoing struggles of parents of school children, anti-hunger organizations, young people fighting predatory marketing of unhealthy food, low wage food workers, and others have shown public officials, the media, and ordinary eaters that food matters and that urban food policy is part of poverty policy, anti-racism policy, education policy, health policy, and more. Another indicator of this greater attention to municipal food policy is the Mayor’s Office’s soon-to-be-released 10 Year Food Plan for New York City, an important tool for monitoring progress that was recently required by law.

Sadly, another great educator on food policy has been the COVID-19 pandemic. Hunger and food insecurity have increased sharply, many low wage food workers face unemployment and unsafe working conditions, many New Yorkers struggle daily to find healthy affordable food. Who could miss the fact that our city’s food system and policies have not been strong enough to deal with this crisis?

A comparison of the two mayoral forums also showed that some issues have yet to move front and center to the mayoral agenda. At the 2021 forum, while several candidates talked about the importance of healthy food, none mentioned that diet-related diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some forms of cancer are now the leading cause of premature death and preventable illness in New York City and the nation and a leading cause of the wide inequities in health between Black and Latino New Yorkers and whites and between low- and higher-income populations. To make more substantial progress in improving the health of New Yorkers, closing income and racial/ethnic gaps in health, and lowering the exorbitant cost of health care, we must make improving the nutritional quality of New Yorkers diets a high priority.

Second, while the candidates did talk about making healthier food more available and affordable—an important goal—none discussed the equally important goal of reducing the availability and promotion of unhealthy food. As long as publicly-subsidized (through agricultural and tax policy) fast food, soda, and highly-processed food are more available and cheaper than fruits, vegetables, and other healthier products, New Yorkers will find it hard to make healthy choices. What city policies could contribute to that goal? Can city government play a role in protecting New York City’s children from the relentless marketing of Pepsi, Coke, McDonalds, Kellogg’s, and others? These are questions the next Mayor should be ready to answer.

Finally, the candidates in the mayoral forum this year, as in 2013, were reluctant to take on the elephant in the room of food policy -- the industrial food system that is remarkably efficient in producing, distributing, and marketing the diet that is sickening New Yorkers as well as the nation and world. Until New York City begins the challenging task of creating a food system whose priority is getting healthy, affordable food to every resident rather than making profit for transnational food giants, it will be difficult to address the deep problems of our food system.

Of course, New York City can’t make this transition alone. But with the state and federal government, with the labor, environmental, women’s, Black Lives Matter, and other movements and with the millions of New Yorkers who struggle to get the tasty, delicious food that will support their own and their children’s and grandchildren’s well-being, we can move forward. The covid pandemic and economic crisis present a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to advance this goal but only a mayor with a vision for a different kind of food system can help New York City chart that course.

Let’s use the next months to give the candidates the knowledge and strength they need to take on that task and the coming years to create the groundswell of public pressure to make New York City the national leader for a healthier, more equitable and sustainable food system.

[Read: Democratic Mayoral Candidates Offer Ideas for Addressing Food Insecurity]

***

Nicholas Freudenberg is Distinguished Professor of Public Health at the CUNY School of Public Health and Director of the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute. The opinions in this column are his own.

*Sponsors of the event were Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center, the NY Covid-19 Food Coalition, City Harvest, the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, Equity Advocates, Food Bank for NYC, Hunger Free America, UJA-Federation of NY, LiveOn NY, United Way of NYC and the Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education & Policy at Columbia University

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Health of Our Cities Depends on DACA, and a Path to Citizenship for Dreamers

DACA supporters (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

President Biden has taken steps to make the lives of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients better by introducing a bill that has expedited a pathway to citizenship for them. While preserving and even fortifying DACA is a necessary immediate step, merely restoring the program’s initial provisions is no longer enough. What we owe DACA recipients is what we owe all immigrants who have contributed to our country: a pathway to permanent residency or citizenship so they can plan a future without fear. Their security and well-being are essential to that of all of us. That is why New York City and cities all across the country are excited to support the Biden-Harris Administration’s Dream Act and U.S. Citizenship Act, which will create such a pathway to citizenship for all of our immigrant communities.

Throughout the Trump administration, the repeated assaults on the DACA program took a significant toll on 700,000 DACA recipients, or “Dreamers,” and their families. Now, despite President Biden’s Executive Order to strengthen the program and a federal court overturning the Trump administration’s bad faith effort to stop the program entirely, DACA still remains in legal limbo. On December 22, U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen in Houston held a hearing in which Texas and eight other states sought to end DACA, and the case is ongoing. Advocates have warned that Judge Hanen’s future decision may be “the worst court decision since the program was created.”

Dreamers play a key part in this pandemic workforce. Over half-a-million DACA-eligible individuals across the country are currently classified as essential workers, with 62,000 working in healthcare alone. If you get sick with COVID-19, there is a chance your nurse or medical assistant could be a Dreamer. Moreover, through their earnings Dreamers power our metro areas, growth that will be much needed to combat the economic impact of COVID-19. Each year DACA and DACA-eligible recipients contribute $4 billion to federal, state, and local taxes, however, they are unfairly excluded from federal benefits like financial aid, social security, or Medicaid.

Thankfully, though, it is not just the Biden administration that supports DACA, but a large political cross-section of the American public. Seventy-three percent of voters want legislation that protects Dreamers from deportation, and 72 percent support a pathway to citizenship. We are encouraged that Senators Dick Durbin and Lindsey Graham reintroduced the Dream Act in the Senate. Yet Dreamers are still made to live on borrowed time, and as such, Dreamers are not able to fully achieve their fullest potential despite their great contributions to the only country they call home.

Consider the difference in establishing a secure life would make for Escarleth Fernandez, who has lived in New York City since kindergarten. Escarleth’s Bolivian parents brought her to the U.S. at age four in search of a better life for their daughter, like the countless immigrants before them. Last year Escarleth graduated from Hunter College, where she majored in media studies. She is passionate about medical technology and currently works as a research assistant in hematology and oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine, supporting patients who are starting cancer drug trials. Successful as Escarleth is, she nonetheless rightly balks at the notion that Dreamers’ worth is defined by their elite career paths. “People want to homogenize us, saying that we’re all going to be doctors, lawyers, or engineers,” she said, “but that’s not a fair expectation.”

What hinders Escarleth from pursuing a master’s degree in public health, however, is her ever-tenuous DACA status. And that makes it harder for her to invest in her future, especially if it requires careful planning and considerable amounts of money to pay for grad school. Even taking out an education loan is tricky; DACA recipients are prevented from applying for much of the traditional federal aid necessary for someone like Escarleth, who is a first-generation college student and whose family’s income cannot afford the hefty grad school price tag. With private student loans, her interest repayment rates would be prohibitively high, given that DACA students are considered “high-risk borrowers” as a result of their impermanent immigration status.

Experts predict it may take New York City a decade to emerge from the pandemic-induced recession. Imagine how much better our communities and economy would be if we helped Dreamers like Escarleth to pursue their dreams. Equipped with her master’s, she would be ready to serve when we face our next public health crisis.

Dreams are not restricted to those with citizenship. With legislative reform like the Dream Act and U.S. Citizenship Act, the 117th Congress has the opportunity and responsibility to provide permanent protections to those in our immigrant communities that are long overdue. The health of our city’s future depends on it.

***

Bitta Mostofi is Commissioner of New York City’s Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. On Twitter @bittamostofi of @NYCImmigrants.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Biden Plan Gives New York State a Two-Year Reprieve from a Damaged Budget

Joe Biden and Andrew Cuomo (photo: governor's office)

President Biden’s stimulus package is proceeding down the legislative path in Congress. This is great news for New York residents and for New York governments’ beleaguered budgets. The $1.9 trillion plan includes $350 billion for State and Local Governments, Tribes, and Territories.

The monies will likely be apportioned in a manner similar to the earlier stimulus package, meaning that New York State, at 6% of the nation’s population, would get close to $21 billion to shore up the budgets of the state government, the city government, and the rest of New York’s municipalities. New York residents would, of course, be getting the direct checks and increased unemployment aid that are outlined through September 2021. The income cutoff levels for the direct checks are still being negotiated and, of course, the final package could still be modified.

A respite of this magnitude could not be more welcome. The city and state governments will effectively get a two-year grace period for their economies to recover from the COVID-19 recession, with budgets heavily sustained by federal aid until the 2023-2024 budget year begins in April 2023. The dimensions of the new federal aid are extraordinary, but there’s no doubt New York will hit a fiscal cliff when the federal money runs out.

How the Biden Plan Will Help New York

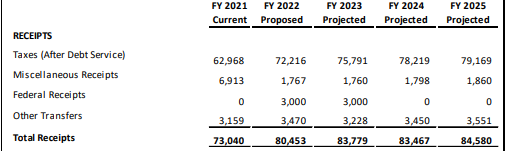

The plan working its way through Congress far exceeds Governor Cuomo’s initial expectations about federal aid in the coming state budget, due for adoption by April 1. Governor Cuomo’s 2021-2022 Executive Budget, submitted to the Legislature on January 19, anticipated a baseline of $3 billion from the new stimulus plan for each the coming fiscal year and the 2022-2023 fiscal year, or $6 billion over two years. The table below presents that assumption. Note that the federal receipts are new anticipated funds, not reflecting the already substantial infusions of federal aid provided in 2020 or 2021 thus far:

The table below is from the submitted Executive Budget showing how a federal funds infusion of $15 billion could offset widespread budget cuts and tax increases in New York over the next two years:

New York’s potential aid in the Biden plan, at an estimated $14 billion, is close enough to the governor’s estimate above to hold New York State’s budget harmless from spending cuts and tax increases for two years. That does not count the additional aid of $7 billion that could be passed through to local governments, assuming New York got a full $21 billion share of the $350 billion aid package for State and Local Governments. The table above does not factor in Enhanced Federal Medicaid reimbursement of an additional $2 billion for New York State approved by the Biden administration after the Executive Budget was released, or funds from Biden’s COVID-19 assistance plan for schools.

A Fiscal Cliff in Spring 2023?

The governor’s budget plan uses federal aid as a substitute to replace state spending. As a result, if no underlying adjustments were made to state revenues and expenditures that were temporarily being replaced, significant deficits would likely reappear in the 2023-24 state budget, even assuming the economy is finally recovering.

The governor’s budget forecast a $6 billion deficit for New York State in fiscal year 2024, which starts April 1, 2023. That forecast assumed the Legislature would enact his proposed tax increase on very wealthy New Yorkers, bringing in $2 billion a year, budget cuts of $3.5 billion in 2021-22, and addressing, in a manner not specified, a 2022-23 deficit of about $3 billion. Failing to enact the spending and revenue adjustments in the new budget due by this April 1 would add to the 2023-24 deficit forecast of $6 billion, adding $5.5 billion to that deficit for a resulting $11.5 billion that year with the extraordinary federal aid in the Biden plan exhausted.

In fact, no one knows what the course of the economy will be over the next two years, along with the state and the city budget deficits. The recovery will be driven by the success of the COVID-19 vaccine and its distribution. New York State coped with a similar size deficit, about $10 billion, in 2011 when the two years of aid from the Obama stimulus package expired, with painful budget cuts. Fortunately, the national and state economies became robust at that time. Once again, New York must restore the health of its economy, and that means the health of the New York City economy, which over the past ten years has been 70-80% of the state’s job growth.

A New York City Comeback?

New York City will have to come back from what may be its most damaging decline since the fiscal crisis of the ‘70s, or even the Great Depression. Tourism and hospitality, the arts, entertainment, culture, international investment, all the prime elements of a premier international city in a global economy, have all been devastated. New York City lost 12% of its employment between December 2019 and December 2020 and nearly 60% of the state’s job losses were concentrated in the city.

The city recovery has lagged the state and nation since the country’s covid lockdown. In fact, the City has only recovered 361,000 of the 944,000 jobs it lost between February and April 2020, or 38%, while the rest of the state outside the city has recovered 52% of its job losses, according to the New York State Department of Labor (my calculations of its data). The January 2021 jobs report just released by the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics showed the nation as a whole has recovered about 12.5 out of the 22.4 million jobs lost since February 2020, or 56%. New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s latest weekly report shows the city economy’s employment growth has stalled since October 2020 (and jobs actually declined in December). It’s not clear that a healthy recovery can really begin until a massive number of New Yorkers has received the vaccine, possibly not until late summer or early fall.

Are New York’s leaders up to the challenge? Can a governor known for his competence but unwillingness to work with others come to grips with a State Legislature with far more progressives in both houses? Can a new New York City mayor halt the state’s discriminatory treatment of the city and actually engage with the governor? Can a consensus about how to solve New York’s problems really be achieved in this divisive era? One thing: the leaders are all Democrats. Can they hold together and chart a path that will keep New York successful?

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Everything Says Put Housing First; So Why Does New York Put Housing Last?

Supportive Housing (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

For several years, perhaps the foremost issue in New York City politics was homelessness. But for all the talk, not much has been done. In fact, things have in some significant ways only been getting worse.

Housing is a human right. It is a physiological need and we cannot have a functioning society without it. Yet our city has made this most basic need one of the hardest to achieve.

Housing First – prioritizing permanent housing for all – must be at the center of any proposed approach. It’s the right thing to do, it’s the most effective thing to do, and it’s the most cost-efficient thing to do.

Unfortunately, New York City couldn’t be further away from Housing First. We can describe our framework as Housing Last.

This urgently needs to be addressed: Over 80,000 New Yorkers are experiencing homelessness – 20,000 of them children. People experiencing homelessness are deemed not “housing ready,” even though most just need safe, affordable housing. For example, about 40% of families enter the city’s Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters due to domestic violence, and another 30% due to evictions.

Instead of prioritizing housing, though, city government explicitly states that shelter clients are required to “gain employment, connect to work supports and other public benefits, save their income, and search for housing to better prepare for independent living,” per DHS.

This perpetuates homelessness instead of preventing it. The average stay in the shelter system has been increasing over the past five years. In the city’s 2020 fiscal year, single adults spent an average of 431 days in the shelter system before achieving independent housing. For families with children, it’s even worse at 443 days, while adult families spent on average 630 days.

Our system forces prolonged homelessness with little hope for stability. I recently spoke to a senior citizen who spent years living doubled up with friends because she could not find an affordable apartment. She had no recent rental history and her income was too low to qualify for available “affordable” housing units. Her only option was to enter a shelter, and become officially homeless, before she could get help finding permanent housing.

This creates an endless cycle. Being homeless makes it harder to find employment, make it to job interviews, and get to work on time. This traumatic experience often leads to substance abuse and mental health issues. In other cases, shelters can be so unsafe that people prefer living on the streets. Children in shelters have a harder time in school, have to constantly change schools, or travel long distances.

Stable housing is also a public health issue. A systematic review of 22 studies found that people experiencing homelessness frequently prioritize shelter and food over seeking health and social care. In a study of nearly 80 health professionals, “facilitated access to housing” was ranked the number one priority for homeless patients, above care for mental health, addiction, and other medical issues. Unsurprisingly, housing stability is associated with reducing preventable visits to the emergency room.

Beyond improving people's quality of life, permanent housing is also more cost effective. According to the Mayor’s Management Report, the cost for temporarily housing a single adult averages $130 per day. For families with children, this number is $202 per day. In contrast, when money is spent directly for permanent supportive housing, people are healthier, and the system is burdened with less medical costs, with an estimated net savings of $10,100 per person. These values don’t include the long-term benefits of increased access to jobs, support services, and stable education.

Many elected leaders have endorsed Housing First...in theory. Last year, the City Council released a 202-page report on the homelessness crisis. The report recommended dozens of policy proposals, the first being to prevent homelessness, the second to Increase Pathways to Permanent, Affordable Housing. But, reports are only as good as the actions taken.

Without enough housing, these goals are a pipe dream. To dig ourselves out of this hole, we need to shift investment from shelters to building affordable and supportive housing in every neighborhood — especially high opportunity neighborhoods.

We know this can work because the city has had success with Housing First-like approaches for military veterans. The New York City Department of Veterans’ Services (DVS) made permanent housing for homeless veterans a topmost priority. The city employs a peer coordinator program, provides incentives to landlords and brokers to ensure availability, and invests in after-care services to help maintain stable housing. Since 2015, New York City has maintained homelessness levels among veterans at “functionally zero” by securing permanent housing within 90 days of entering the shelter system.

Another success was the New York/New York III program, a city-state pact that has provided supportive housing for homeless individuals with serious mental illness, substance abuse, and disabling medical conditions, resulting in fewer days in jails, shelters, and medical and psychiatric facilities.

These programs provide a model for making an immediate impact. The first is setting a time limit from shelter entry to permanent housing. Second is to eliminate barriers for people to receive rental assistance and be able to “graduate” out of the shelter system. Finally, we should spend more on rental assistance and less on shelters.

Ultimately, we should prevent people from entering the shelter system in the first place. Making this a reality requires the city to integrate homelessness and affordable housing policies. These are not separate issues, but rather a cause and effect that are tightly connected.

It’s time for Housing First on a meaningful scale. Housing is the foundation for a better life, and a better city. As we reset New York in the 2021 election cycle – it all begins with a commitment to fully realize Housing First.

***

Sara Lind is an attorney, community activist, and mother of two running for City Council in District 6 on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. On Twitter @saraklind.

Research and Contributions by Tiara R. Ahmad, PhD of Science for New York (Sci4NY), an organization that helps connect local scientists and decision makers through project-based interaction.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Attorney General’s Lawsuit Against the Mayor and NYPD is a Needed Option

The Mayor and PC Shea (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Last month, New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a groundbreaking lawsuit against the City and the NYPD “to end the pervasive use of excessive force and false arrests by the NYPD against New Yorkers in suppressing overwhelmingly peaceful protests.” The suit was in response to the NYPD’s use of force at last summer’s racial justice protests. The complaint alleges multiple examples of excessive force, and presents a detailed critique of the NYPD’s handling of both the summer protests and many other peaceful protests that came before.

Litigation seeking systemic reform is a long and messy process and should never be a first resort. But because Mayor de Blasio has consistently refused to make necessary reforms to the NYPD even when given specific roadmaps about how to do so, litigation is now the most promising option on the table. Indeed, as the Attorney General’s complaint points out, nothing short of a federal monitor has yet to change the Department’s behavior in this area. To that end, the complaint alleges that the NYPD has engaged in unlawful practices against peaceful protests for years and failed to voluntarily take corrective action despite multiple warnings in the form of reports and lawsuits. A failure the Mayor and Police Commissioner now concede.

We have seen this process play out in similar circumstances ourselves. For five years we ran the City’s Department of Investigation, which oversees the NYPD’s Inspector General. During that time, we issued several reports on systemic failures that were largely brushed aside by the NYPD’s top leadership and the Mayor. Most importantly, in 2018 we issued a Report that demonstrated that the NYPD repeatedly failed to properly investigate sexual assault and continuously failed to properly staff and train the officers responsible for these investigations. Despite the Report, and despite the protests and City Council hearings it fostered, the NYPD failed to take action on its most central recommendations.

Moreover, these were not new problems. During our investigation into the Special Victims Division, we discovered that an internal 2010 report had come to the same training and staffing conclusions and thereafter there had been repeated complaints from the head of the unit about these problems. So, the NYPD had been ignoring these issues for at least eight years. The Mayor and Police Commissioner were unwilling to insist on key police reforms, even where rape cases were often poorly investigated or at times not investigated at all. According to the NYPD IG’s most recent Annual Report issued last year, over half of DOI’s recommendations regarding investigation of sexual assault remain unimplemented.

Another example – which has disturbing echoes of the problems identified by the Attorney General in her lawsuit – involves the NYPD’s reporting on use of force. In a lengthy Report in 2018, DOI found that the NYPD, despite promises to the contrary, was failing to properly monitor, track, and report on the use of force by its officers. Specifically, although the NYPD had created a Threat, Resistance or Injury (TRI) form to track use of force, too often officers either failed to fill out the form or did so improperly. Again, the Police Commissioner and the Mayor refused to make significant changes – as of the most recent reporting by the NYPD IG, over half of the recommendations have still not been fully implemented.

Indeed, according to the most recent Annual Report from the NYPD IG, just slightly over half of all recommendations made since 2014 by DOI to the NYPD have been fully implemented. And these recommendations themselves were the subject of extensive discussions between the IG and the Police Department before they were ever published. They are not recommendations issued in a vacuum without consideration of the realities of modern policing.

None of this is intended as an overall indictment of the 36,000 officers in the NYPD – the vast majority of whom do a difficult job exceedingly well. Indeed, calls to defund the police miss the mark and will not result in necessary reforms. We do not need a vastly smaller police force; we need a police force that reforms certain specific dangerous and unconstitutional practices. A federal monitor of, rather than defunding, the police is the best way to get there.

Two arguments have been raised in opposition to the Attorney General’s lawsuit: First, that the NYPD already has multiple monitors and second, that last summer’s protests presented a volatile situation that was difficult to police. While both statements are true, neither, as an argument, should prevail. As to the first, while there are multiple NYPD monitors, none, in this area, have the backing of a federal court and thus the NYPD has felt free to disregard the monitors’ recommendations. As to the second, policing protests is certainly difficult; however, that is exactly why it requires proper training and must be done correctly.

It is important to acknowledge that the monitor sought here would only deal with the one issue raised in the Attorney General’s lawsuit. Nevertheless, monitorships have been powerfully effective in the past, most recently in reducing the use of stop-and-frisk. A monitorship here could give the hardworking officers in the NYPD the tools they need and the training they deserve to be better partners with the community.

This Mayor and his police commissioners have repeatedly shown an unwillingness to make needed changes even when confronted with evidence of problems. If they haven’t taken steps they’ve known were needed for the last seven years, it’s hard to imagine they will do so now. For this reason, we’ve reached the point where a federal monitor to force change on the NYPD is the best option for this Department.

***

Mark Peters and Lesley Brovner are the founding partners of Peters Brovner, LLP and from 2014 to 2018 served as Commissioner and First Deputy Commissioner of the Department of Investigation, the City’s Inspector General.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.