To Build a More Inclusive New York, We Need to Reform County Parties

New Yorkers (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

As Governor Andrew Cuomo continues to face a barrage of scandals, from sexual harassment accusations to his catastrophic mishandling of the state’s nursing homes during the darkest days of the pandemic, many New Yorkers rightly wonder how the governor and his confidantes have managed to amass so much power in the first place. It’s long been a “best-kept secret” in New York politics that the Democratic establishment, including Governor Cuomo, controls our city’s and state’s politics with an iron fist.

There is an important and overlooked piece of this puzzle that renders politicians like the governor essentially untouchable: the county-level Democratic parties. Until we reform the county party system and put power back into the hands of the people, a small group of elected officials, like Governor Cuomo, will continue to hold too much power, insulated from the constituents they claim to serve, and acting only in their own interest.

Fortunately, there are clear reforms we can make to the county party system to democratize the Democratic Party and build an open, progressive, and accountable party.

First, county parties must allow for real engagement from rank-and-file Democrats, instead of consolidating power to serve a narrow range of entrenched interests. That means genuinely opening meetings to rank-and-file members — and soliciting and valuing their input, something that is all too rare and actively discouraged by party leaders these days.

In December, for example, the Brooklyn Democratic Party held its organizational meeting. A large and diverse coalition of members sought to pass rules to open up the process and encourage participation. Instead, what followed was a 25-hour meeting over two days, where people were silenced on Zoom, points of order weren’t allowed, and hundreds of people were disenfranchised. Bizarre irregularities also arose in vote tallies for several proposed rule changes.

That sure doesn’t sound democratic, but that’s exactly how the county party wants it to be. The very same Brooklyn Democratic Party used the pandemic as an excuse to not hold meetings at all.

Second, we also need to reshape the County Committee structure to ensure the party is accountable to members. The County Committee is an elected body that decides county party business, including voting for party leadership, passing a party budget, and voting on other resolutions. In my work with New Kings Democrats (NKD), we recruited progressive candidates to run for County Committee, and created Rep Your Block to make it easier to do so. The party establishment fiercely opposed these efforts, even sending people door-to-door to canvas for proxy votes while claiming to be from NKD — and actually taking their votes for the party-aligned candidates.

That proxy voting system effectively allows party bosses to hold hundreds of votes in their pockets, ostensibly from community members, and use them to quash unwanted, but necessary, reforms. We need to overhaul and replace the proxy voting system to give community members just as much of a say as party leadership.

Third, we need to minimize the ability of party leadership at all levels to put its finger on the scale and unfairly influence elections. Recently, State Democratic Committee Chairman Jay Jacobs issued a scathing statement criticizing candidates who dared mount a progressive primary challenge against Rep. Carolyn Maloney. Instead of lambasting grassroots activists and unleashing bad-faith attacks against anyone who rightly asks questions of incumbent candidates, the Democratic Party should welcome debate and disagreement. The same is true of county parties, which exist to protect incumbents and entrenched interests, at the expense of democratic values.

While these sound like minor changes to a complicated system, they are necessary steps toward our goal: To create a Democratic Party that represents its members and encourages their participation. They may not change our politics overnight, but they will loosen the stranglehold a small group of powerful politicians has on our political system.

We need to transform our county parties from being transactional vestiges that benefit those at the top, to responsive, accountable organizations that fight for the people. New Yorkers want politicians that represent their interests and their communities. We can start by reforming our county parties and giving the grassroots a chance to grow.

***

Brandon West is a candidate for City Council District 39 in Brooklyn. On Twitter @brandonwestnyc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Other Civil Rights Revolution of 2020 That We Must Now See Through

Pride (NYC Mayor's Office)

While millions of Americans marched for Black Lives and racial justice in our streets during a year of racial reckoning that was 2020, a quieter civil rights revolution was taking shape in our courtrooms, culminating in a Supreme Court decision last June that shifted the tectonic plates of the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights. With a new President who has been a leader in this fight and transgender students becoming the latest target in the GOP’s culture war, now is the time to ensure the full promise of this decision touches the lives of the LGBTQIA+ community, starting with where they live.

I write this as a public servant deeply committed to LGBTQIA+ rights and as the former Housing Secretary under President Obama, when I was the first sitting Cabinet member ever to endorse marriage equality. I believe the next frontier in the fight for gay rights must begin with housing those who are most vulnerable: LGBTQIA+ youth, seniors, immigrants, the formerly incarcerated, and people of color.

Since the towering civil rights laws were written in the 1960s, a fundamental question has run through the legal underpinning of the gay rights movement: does discrimination on the basis of sex, which underlies the movement for gender equality and is clearly prohibited by these laws, also apply to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity? Without a clear answer to this question, LGBTQIA+ Americans had been largely orphaned from the protection of our justice system.

But then last June, the Supreme Court ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County that “it is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex.” Before you counter that this earth-shifting statement came from a Supreme Court that still included Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, understand that these words were written by Justice Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, for a 6-3 majority. With this potentially durable victory at the highest court in the land, we must press forward to advance the cause of LGBTQIA+ rights, and the agenda begins at home.

The new federal administration has taken the most critical first step to enshrine the promise of the June Supreme Court decision by extending its reasoning to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which was passed just weeks after the assasination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Bostock v. Clayton County interprets the language of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and applies it to workplace discrimination. But because the Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination in housing, both public and private, on the basis of sex, the logic of the decision’s conclusion will be applied to the later law as well. Now the federal, state and local government must make this promise real by enforcing the law.

Here in New York City, the results of the recently completed National Transgender Discrimination Survey make clear that many of these city residents continue to struggle on the housing front. Among the city residents who completed the survey, 8% reported being evicted, 19% denied a home or apartment, and 18% becoming homeless as a result of their gender identity or expression.

The next critical step the Biden-Harris Administration should take is ensuring HUD’s Equal Access Rule remains the law of the land. Created by two Obama housing secretaries, myself and Julian Castro, the rule requires equal access to HUD programs without regard to a person’s actual or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status. Lasy July, Trump Housing Secretary Ben Carson issued a proposed rule that would replace it, using the specter of transgender people accessing homeless shelters and other services based on their gender idendity, rather than the gender they were assigned at birth, to demonize transgender people and curtail LGBTQIA+ rights. Since the proposed rule was not finalized in the closing days of the Trump Administration as expected, the Biden-Harris Administration should take immediate steps to withdraw the proposed rule and reestablish the original Equal Access Rule.

Finally, our federal, state, and local governments should work together to extend the promise of the Fair Housing Act and Equal Access Rule into lasting change by ensuring the most vulnerable LGBTQIA+ people can find decent, safe, affordable housing. After all, ending discrimination is not enough if the historic damage of intertwined inequality isn’t attacked head on. LGBTQIA+ youth are more likely to end up homeless than any other demographic, and aging transgender and queer people are the most susceptible to housing discrimination. Other at-risk groups include the formerly incarcerated, immigrants, and people of color, and COVID-19 has only magnified the systemic inequities that face them in New York City and across the country.

In New York City, we should be proud of examples like True Colors, the first permanent supportive housing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth with a history of homelessness. Now we must build on them. With President Biden’s American Rescue Plan providing more than $20 billion in emergency rental assistance and the American Jobs Act proposing more than $200 billion for housing, we have a chance to translate victory in the courts into real change in the lives of our neighbors. By partnering with new HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge, who is committed to putting equity first, New York City can become a beacon for the rest of the nation. Housing is a basic human right. It’s time we make that promise real for our LGBTQIA+ community.

***

Shaun Donovan is a candidate for New York City mayor. He served in President Obama’s cabinet for eight years, first as Housing Secretary and later as Budget Director, and as Housing Commissioner for Mayor Bloomberg. On Twitter @ShaunDonovanNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How the Next City Council Can Prepare Communities for the Next Pandemic

Emergency department (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office )

As New York finally begins to lift health restrictions related to the novel coronavirus, the next generation of leaders need to take the necessary steps to ensure that when, not if, another pandemic comes to our communities we are better prepared. Unfortunately, this time around too many communities of color, like in Southeast Queens, lacked the necessary resources and infrastructure to effectively handle this crisis; we cannot let that happen again.

Fortunately there are already several policies within the city’s toolbox that would not only put the right resources where they are needed, but also make sure communities have a say in how residents are able to access the health care they need. With a new class of City Council members coming into office next year, there will be an opportunity to put forth new ideas, with new energy, to address the city’s health needs.

Southeast Queens, where I have lived for over 20 years, was one of the hardest hit communities by COVID-19. In March of 2020, when the first wave of the virus hit, our communities quickly had some of the largest percentages of people who were testing positive, and both Jamaica Hospital Center and Queens Hospital Center were overwhelmed with patients diagnosed with the coronavirus, and death rates surpassed the awful citywide average.

This was a disaster that was years in the making. Between 2008 and 2012 four hospitals in Queens closed: Mary Immaculate in Jamaica, Parkway in Forest Hills, St. John’s in Elmhurst, and Peninsula Parkway in Far Rockaway. It was also incredible to hear about cuts proposed by the state this year, during the middle of the pandemic, to Elmhurst Hospital and St. John’s Episcopal Hospital.

The closures and funding cuts were put forth as necessary cost-saving initiatives; but clearly communities lose when health care facilities close. Anyone who lives in Southeast Queens knows the lack of community-based general medical practitioners that residents can access for their everyday health needs, and elected officials need to take the lead in fixing this problem.

To alleviate some of the financial burdens our city’s public Health + Hospitals system currently endures, the City Council can shift back Emergency Medical Services (EMS) revenue from the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) to New York City Health + Hospitals. In 1996 then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani signed Local Law 20 merging EMS into FDNY, which moved the funds out of the hospital system. In Fiscal Year 2021 EMS revenue was a little over $339 million. Think about where the ambulances are going: not back to the fire houses, but the hospitals where the people they are trying to save need to be.

It does not make fiscal or practical sense for EMS to be funded through FDNY, and this is money that can be better served by the hospitals that the ambulance workers already coordinate with most. This new revenue into the system would allow more flexibility within it, helping to prevent any other hospitals from being closed in the future.

In order to ensure the community has a voice in any new health policies that are enacted, the new class of City Council members should convene task forces in their offices that bring together everyone in health care — labor leaders, community boards, health care professionals, elected officials, and community advocates — to specifically identify and address districts needs. Having an organized front will help ensure there is one voice coming out of each community so decision-makers in Albany, City Hall, and the relevant agencies know where they stand and the policies they want to see implemented.

Also, each community board can be allocated funds to develop its own health-care plan through the 197-A process, where city agencies would be mandated to implement the recommendations through their regulatory processes. This approach guarantees the policies we request will come to fruition so residents in the district can receive the medical care they deserve.

The next city government needs to take on health care directly and assertively. We’ve seen why. If we come together, we can improve health-care access for those living here today and for the future residents of New York.

***

Al-Hassan Kanu is a candidate for Council District 27 which includes the communities of Jamaica, Hollis, St. Albans, Queens Village, and Springfield Gardens in Queens. On Twitter @kanuforcouncil.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

If All Politics Is Local — How Do We Get People to Vote Local?

Student voter registration (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office))

As New York City heads into the final stretch of the 2021 local primary elections, candidates will be working overtime for votes. If history serves as a guide, turnout will be low. While so much effort goes into registering people to vote and getting them to the polls, we should focus more on indirect measures that can have larger impacts. This includes shifting the local election cycle timing and teaching about civic engagement in our public schools.

Only about 15% of eligible voters in New York City turn out to elect local leaders. For special elections, it is generally much lower. In the two elections held in The Bronx this year, it was around 4% in City Council District (CD) 15 and 10% in CD 11. In comparison, the turnout for registered voters in New York City was 55% in the 2020 presidential election.

The difference in voter turnout for a federal/state level election year versus a local only-level election year is not unique to New York City. Nationwide, pairing higher-profile elections with less-followed local races amplifies down-ballot voting by at least a factor or two. Notably, when Baltimore shifted its local and presidential elections to coincide in 2016, local voter turnout increased from 13% to 60%. New local ranked-choice voting (RCV) in New York City for primaries and special elections isn’t expected to significantly impact these outcomes on its own.

Low voter turnout has many negative consequences. One is basic math – the fewer people that vote in an election, the less likely it is that those elected will reflect the interests of the average constituent. To put this in perspective for New York City, many City Council races are decided by a differential of approximately 1,000 votes. This translates to around 1% of a district’s population determining the council member. For Mayor de Blasio, the turnout was higher, but still low – with about 1 out of every 7 registered voters in New York City voting for him for a second term.

Under these low voter turnout circumstances, another particular issue is that high-net worth individuals can amplify their influence on the local electoral process. This reduces the impact of the small-dollar public matching funds program, developed precisely to limit that kind of outcome.

With several special elections, larger primary candidate fields (thanks to the public matching system and perhaps also due to RCV), and expanded early voting, substantially more taxpayer money will be spent this year than usual. If voter turnout remains generally low this year, another adverse outcome is that this extra spending will not achieve the goal of incorporating the voices of more New Yorkers in the electoral process.

Combining elections at different levels of government in a single year and on the same election dates would not only substantially improve local civic engagement, but also offer cost savings. For a reference point, estimates predict reductions of $2.3 million every two years for holding a joint federal and state level primary in New York City.

While changing New York City election timing to even years to coincide with federal and state-level positions would be a huge step in the right direction, it is not the only missing piece of the voter turnout equation. Most voters lack a fundamental understanding of their local government, including how it operates, who is running it and running to serve in it, and how its actions affect their lives. RCV amplifies these education-related needs, so that voters study all of their primary and special election choices to be able to rank up to five candidates per race. At the same time, RCV is also expected to help encourage more candidate outreach to a wider swath of voters.

Though harder to quantify than other voter turnout efforts, the lack of basic civic education has real-world significance. In a December 2020 poll of Democratic Party voters in New York City, all of the issues they prioritized locally, to some degree, are impacted by New York City’s elected officials. Other metrics also help tell the story – as the city government’s 59 elected officials make choices that affect its 8.4 million residents, including about 325,000 city government employees, while overseeing a budget of more than $90 billion.

A classic example of local government confusion is the age-old question ‘Who runs the subways?’ Pre-pandemic, over 6 million people daily used the subways, with several million more on the buses. However, in a 2016 poll, 47% of respondents believed that the mayor was responsible for the transit system. Hint: That’s not correct.

The City has attempted to address education gaps in its public schools by introducing the Civics for All curriculum in 2018, which includes civic engagement-related material covering federal, state and local government. These materials allow educators to expand upon narrow, almost exclusively federally-focused civic education requirements in public schools.

On the downside, Civics for All is rather limited – with no requirements that schools institute the program. Funding to widely implement the program is also lacking. Mandating these civic education classes, with the accompanying financial support to do so effectively, would be a meaningful change in New York City.

New York City should also look toward prioritizing and expanding its participatory budgeting efforts, which allow youth ages 14+ to participate. This offers a real-world opportunity to create equity and civic engagement both pre-voting age and beyond the standard local election cycle. An analysis showed that when a New York City Council District adopted participatory budgeting, it spent more on schools, public housing, and streetscape improvements than it would have done otherwise.

When all the votes have been counted and the large sums of money have been spent on the 2021 New York City elections, we are likely to be left with the same persistently low voter turnout problems. We need to seriously address civic education and the timing of our elections if we’re going to notably change these outcomes. We know the way -- we just need to demand that elected officials have the will.

***

Nancy Holt, PhD leads Science for New York (Sci4NY), an effort that aims to bring local scientists and decision-makers together through project-based interaction. On Twitter @Sci4NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hindsight 2020: Why New York’s Trusted Community Groups Are So Important to the Census Count

New Yorkers get counted (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The national census headcount happens every 10 years and is the most democratic process we undertake, also making it the largest competition that states can participate in. The population estimates, which are derived from the count, are used to distribute the 435 seats in the House of Representatives amongst all 50 states. The data collected on who we are isn’t only used for apportionment, it’s the best data that federal, state, and local governments, businesses, and universities will have about who New Yorkers are—and affects all other data collected for the next 10 years. This count is vital to New York’s COVID- 19 recovery, decisions about where to build schools or expand businesses, and a wide range of other plans that we have for the future.

The decennial count is always a heavy lift for the Census Bureau, states, and communities. This time around, there was a lot of reason to fear that New York would not have a fair chance of earning its equitable share of representation in the House of Representatives or the billions of dollars in federal aid that gets allocated based on census data. From the Trump administration’s attempts to require an intimidating question about citizenship, to suppression of the count by ending the door-knocking and response time early, to the global pandemic that severely delayed the start of the Census Bureau’s in-person follow-up, 2020 was by far the most controversial census count in memory. It is a victory that New York didn’t see a further drop in representation in Congress.

Although New York was projected to lose up to two seats in the House of Representatives, we lost just one, and came incredibly close to not losing a single seat. We were only 89 people short of retaining our 27th seat in the House. The count shows that the total state population was 4.2% higher than in 2010—indicating that the state is growing—but other states have grown faster. When it comes to the census, everyone counts, and these results make it painfully clear. Advocates across the state worked tireless in the years leading up to the count to reinforce this message.

Community-based groups always play an important role as trusted voices promoting full participation in the census, particularly in communities that may be hesitant about filling out government forms. In preparation for this work a broad coalition of groups came together under the banner of New York Counts 2020, led by the New York Immigration Coalition and with participation from a broad range of racial, ethnic, immigrant, LGBTQ+, religious, health, education, labor, housing, social services, civic, and business groups working in partnership with Complete Count Committees and state and local government officials.

In the runup to the 2020 census, the Fiscal Policy Institute joined the New York Counts 2020 coalition, calling on the governor and state legislature to support community-based organizations to help the state achieve an accurate count. FPI provided an analysis showing how much was needed: $40 million statewide, with a breakdown of what was needed in each county.

Even before the covid pandemic, we knew that this would be a much more difficult climate to get people to respond to the ten-question survey. The unforeseeable delays brought on by the pandemic made everything about the census more complicated. Community groups began education campaigns years in advance of the census to overcome these obstacles. The fact that 20.2 million New Yorkers were counted is a testament to the tireless work that unpaid volunteers and paid Census Bureau workers put in across the state.

New York State could have been better prepared for the decennial count even before the lockdown orders that forced doorknockers and volunteers to stay home.

In the fiscal year 2021 (April 2020-March 2021) budget New York State invested $30 million to support all 62 counties, cities, and community-based organizations in their census outreach efforts. That’s less than the $40 million the Fiscal Policy Institute analysis suggested was needed, but, through significant investments from the New York City government and some investments in individual counties eventually put the total close to what FPI proposed.

A big shortcoming was the time it took for the funding to get to the groups doing the work. There is often a long road between the time state funding decisions are made and the time the money gets disbursed, but the census outreach funding was far beyond the norm.

Governor Cuomo convened a Complete Count Commission that began its planning for the state’s census outreach in January 2019, the same month its final report was due. This delay impacted every subsequent stage of the state’s census outreach. Ultimately, some of the state funding for cities, counties, and community-based organizations was distributed in July 2020, four months after the start of the count, at the bitter end of the count when many groups were wrapping up their efforts. Because of the last-minute scramble many we know that not all of the funding that was allocated was actually spent. Imagine how many more people could have been counted if there was a timely investment in the organizations across the state who helped count New Yorkers.

In the end, 89 people is so close that it’s impossible to say whether the state could have saved another House seat if, for example, community groups had been funded and supported earlier or more fully. We don’t want as many seats as we can get, but we do want our fair share.

Still, losing only one seat is relatively good news, and a tribute to the tremendous work of community-based groups both before and after they were funded to do outreach. Most models predicted New York would lose two House seats. The final census outcome shows how important it is for states to invest in census outreach at the grassroots level, and that it needs to happen sooner rather than later.

***

Shamier Settle is a policy analyst at the Fiscal Policy Institute. On Twitter @FiscalPolicy00.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

An Emergency Correction to City Voter Disenfranchisement

Voting issues (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Jim Crow remains alive and all too well in Georgia, Florida, and, yes, New York City, where the most diverse field to seek the mayor’s office is preparing for June’s primary.

You know about news from Georgia, where Republicans -- citing false claims about fraud in the 2020 election -- have pushed through a law that, among other things, transfers some of the power to run Georgia elections from the secretary of state and local counties to a state board that conservatives will dominate. The law includes a ban on providing food and water to people waiting in line to vote.

You also likely know the challenges placed on Florida voters. In the run up to the 2020 elections, state Republicans stunted the state’s amendment granting voting rights to people with felony records. Republicans inserted a poll tax requirement that made those with felony records pay all fines and fees from their sentence before they could vote.

However, you likely don’t know the challenges New York City voters have. In New York, a decidedly liberal city, people in pre-trial detention are free to vote. However, as the June 22 primary nears, featuring hundreds of candidates representing the city’s diversity for dozens of local offices, the New York Department of Correction is not meeting its obligations to voting access. The majority of people have not received voter registration information, there are no posters or signs with voter information, and people have not received voter registration education. The failure to take these steps increases the barriers to voting among this population.

The New York City Charter requires DOC to implement a program to assist individuals with voting. Because eligible people in New York City jails are required to vote by absentee ballot, they must rely on DOC staff to exercise their rights. More importantly, a loophole further disenfranchises some in city jails. The last day to postmark an application for a ballot this year is June 15 and the last day to postmark a ballot is June 22. This means eligible voters admitted into custody after June 15 and held through June 22 won't be able to vote.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, Deputy Mayor Phillip Thompson, Board of Correction Executive Director Margaret Egan, new Department of Correction Commissioner Vincent Schiraldi, and the Board of Elections must listen to the Legal Aid Society and ensure voters in New York City jails have prompt and secure ballot access without hindrance. To accomplish this, they must do the following:

Provide a report on what steps have been taken to implement the voting policy in New York City jails announced last year at the September Board of Correction meeting.

Show that the BOC works with the DOC and the Board of Elections to get "emergency" poll sites set up in every jail, and allow every eligible incarcerated person to register and vote by affidavit during early voting (June 12-20) or on primary election day (June 22).

Prove the BOC requests from the DOC and the Board of Elections to report the number of eligible voters in DOC custody, the number of registration forms received, the number of registration forms they considered valid, the number of absentee ballot applications received and accepted as valid, and the number of absentee ballots received and accepted as valid.

There is a lot of confusion and misinformation surrounding access to voting. Ensuring appropriate accommodations for all voters — south and north of the Mason-Dixon Line, in jail or free — is the crucial first step in protecting a fundamental right to our democracy.

***

Ashish Prashar is the Global CMO at R/GA and a justice reform activist. He sits on the board of Exodus Transitional Community, Getting Out and Staying Out, Just Leadership, Leap Confronting Conflict and the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice. On Twitter @Ash_Prashar.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Moving Toward a Full Reopening of New York City Schools — The Time is Now

Kids back at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

On Tuesday, April 27, my kids returned to full-time in-person school for the first time since Friday the 13th of March, 2020. But approximately 600,000 kids in New York City are still learning from home. We must do better.

One surprising outcome of this pandemic: My three elementary school daughters -- Sadie, Juno and Ruby -- were thrilled at the promise of more time in the classroom. Their first morning back had the first-day-of-school energy as they giggled at reuniting friends they hadn't seen for a year and rushed in to see their enthusiastic and prepared teachers. In their words, they were "excited and scared at the same time." And the crowd of parents matched their emotions. As the kids literally skipped into schools, parents effusively thanked teachers and administrators. It felt normal...in the most joyful way possible.

We've been more fortunate than most during this period of at-home schooling -- mostly healthy, mostly employed, with flexibility in our professional schedules that have allowed us to create alternatives to Zoom School. But the chance to go back into a classroom -- where a trained professional can invest deeply in their education and where they can interact with their peers -- are academic and social-emotional opportunities we just can't give them at home.

This return was made possible by a few changes: The reduction of social-distancing guidelines from six feet to three feet for elementary schools; the discarding of the ‘two-case rule’ that had led to countless closures and disruptions across the city based on a dubious public health basis; and the additional opt-in period (something we’ve advocated for since the fall) means more of their classmates can rejoin them. Add in the increasing evidence that schools have not been a cause of significant community covid spread and the accelerating pace of vaccinations, and it feels like a safe opportunity to end the school year with nine or so weeks closer to normalcy.

But here's the real issue: What's good for my kids isn't actually solving the problem for most kids around the city. After the latest opt-in period families decided to return roughly 51,000 students back into school buildings. With a school system that serves more than 965,000 traditional public school students that means that 62% of New York City students will not enter a classroom this year, the vast majority of which are students of color. It's clear that the city must do more to hear and meet the concerns of their families if we're to have a successful, equitable full-time reopening in the fall.

So we must continue to raise the alarm: without a clear vision for the fall that's prioritized and resourced now -- something I and others have been calling on the city to provide for many months -- we won't actually have full-time, in-person school for many New York City students, and that will hurt all of us.

There are many reasons families aren't yet returning -- and I’ve been talking to parents and administrators across School District 15 as well as around the city about these reasons. Some are waiting until their families or communities are fully vaccinated. Some want to see how the covid variants play out. Many chose not to opt in to this final period because they have a house-of-cards schedule of childcare that could fall at any moment and it cannot be altered. And for some students remote school removes social anxiety and distractions and is better for their learning.

But it's also become clear that many parents just aren't willing to place a bet on the Department of Education. Years of underfunding have left schools in disrepair, classrooms crowded, and many kids behind. If your school didn't have soap in the bathrooms pre-pandemic, you may not believe the school would have the resources to ensure regular hand-washing. If your classroom was overcrowded to begin with or if you experienced high teacher turnover, you might not think your child's best interests will be served during these uncertain times by heading into uncertain classrooms.

I was frustrated that the city wasn’t collecting or sharing the concerns of remote families in a transparent way, making it impossible to address those concerns. So I decided to ask remote families directly, and working with City Council Member Brad Lander, we had a team of volunteers survey a geographically and racially representative set of parents and caregivers around the city about their plans for the fall. Some news was encouraging: A significant majority plan to return to in-person school in the fall. Other news less so: Most families said they hadn’t been asked about their fall plans yet. Many families brought up specific health questions the city needs to address, and 8-15% said they are unlikely to return to in-person school, which can give administrators and city leaders some guidance for their planning. And one other important note: Principals are the most trusted voices on returning to school for these remote-only families, more than teachers, and far more than the Schools Chancellor or Mayor.

To get more students back in the classroom, we need to ensure schools are truly open five days a week, limit unnecessary closures that create disruptions for families, make sure teachers and staff have had adequate access to vaccinations, and ensure vaccination requirements align with other requirements across our system. Parents need schools to resume early drop-off and afterschool programs -- both for the enrichment of the students and the consistency of schedule. Our high school students must be taught by in-person teachers instead of reporting to classrooms to learn via video. And all of this needs to be communicated proactively and repeatedly, ideally by principals and teachers, who also use this as an opportunity to listen to remote families, ask about their concerns, and help address them.

Furthermore, parents need to understand the alternative: There has been talk of a remote option being offered for the fall, though there are no details or plans. Will that be provided by each school -- overburdening principals to create dual programs for another year -- or run district-wide? Will it be a citywide one-size-fits-all remote curriculum, or a series of remote academies, conducted in different languages and focusing on different learning styles? Until families understand these details, many may not commit to coming back, leaving principals uncertain about enrollment numbers and unable to make clear staffing plans, ensuring a late summer of confusion and frustration for administrators, teachers, and families.

We are seeing an unprecedented infusion of funds into our schools and how that money is spent will speak to our priorities as a community. We could decrease class sizes, expand enrichment opportunities, ensure multilingual communications, add individual and small-group tutoring capacity, invest in community-wide digital literacy, and so much more. And we can try to hold onto some of what schools have experimented with this year: smaller cohorts, more outdoor time, individual learning, a move away from standardized tests. But until we hear that vision -- and help shape it -- many families might imagine a return to in-person school will be reverting to the models that weren't working pre-covid and continuing some that haven’t worked during covid.

Every day that there isn't a clear vision for the fall -- one that truly dives deep into listening to parents, beyond surveys, including through the many community-based non-profits outside the Department of Education that are serving our families and kids on a regular basis; one that draws a clear, consistent picture of what schools will look like, as best as we can know; one that gives us confidence that the "plan" won't change every few weeks, that it will keep our students and teachers safe and, just as critically, be engaging, enriching, and joyful -- is a barrier to a healthier, more equitable, more successful reopening. Our surveying is just a start to understanding these concerns and providing a roadmap for the city -- but we can build on this with more engagement citywide, including empowering principals to reach out to parents to hear their concerns, answer their questions, and give them confidence to come back in-person.

My kids have the privilege of attending a public school where the administration communicates with us through multiple channels and where the Parents Association can fund additional recess coaches to make outdoor time part of every day (including, now, lunchtime), and where, as English speakers with digital literacy, we're able to absorb the range of updates from our teachers, administrators, and city officials. And they’ve had the benefits both of our employer-based health care and of accessible covid testing locations, plus parents, grandparents, and aunts who have all had the opportunity to get fully vaccinated. All of that just isn't true for large numbers of our city's families.

As a result, my kids are back in a classroom, with professional teachers and many of their friends, while many are not. And if that continues in the fall, it'll exacerbate the inequities and segregation in our educational system even further. The promise of a safe and equitable full school reopening needs to work for all students and families, not just mine.

****

Justin Krebs is a parent of three elementary school students in Brooklyn, New York, a parent leader at his own school and in the community school district Presidents Council, and a candidate for City Council in District 39. These perspectives are his own and do not represent the Parents Association or Presidents Council. On Twitter @justinmkrebs.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

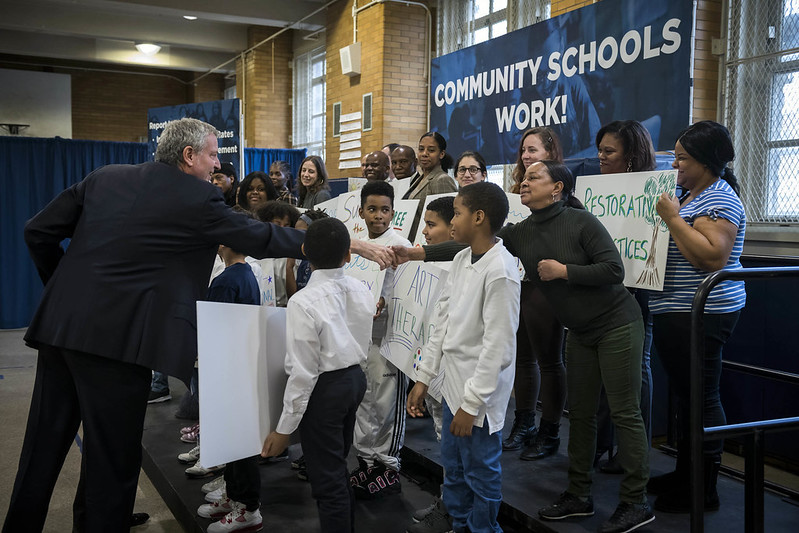

Community Schools are the Answer: An Open Letter to the New York City Mayoral Candidates

A community school celebration (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Dear Candidates for Mayor:

Among the myriad issues you are discussing during public forums and interviews, none is more important than the education of New York City’s children and adolescents. You have responded to, and raised, several aspects of our educational landscape in these venues but we have heard precious little about whether you support expansion of the city’s community schools initiative, an effort that began in response to a de Blasio campaign promise in 2013—a promise on which he and his administration more than delivered.

Especially now, as New York City recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, voters want to know what you propose as viable strategies to promote health, healing, and learning. In my view, the best answer is community schools.

Community schools organize school and community resources around student success. In 2013, candidate de Blasio said he would increase by 100 the number of community schools in New York City. By the end of his first term, the actual number had increased to more than 250. City Hall and the Department of Education worked together to leverage leadership and funding that allowed these schools—chosen according to the level of unmet need among their students and families—to marshal additional human and financial resources. In alignment with national best practice, each school conducted a thorough assets and needs assessment and then engaged community partners that brought the requisite skills, services, and supports into their schools on a consistent basis.

Even more important than the number of community schools are the results they have achieved. A multi-year impact study of the initiative conducted by the RAND Corporation reported a reduction in student chronic absence as an early outcome and, later, found an increase in academics and graduation rates for all students—particularly for students living in temporary housing and for Black and brown students.

These results were achieved through the mobilization of community resources and their integration into the core instructional work of these community schools—resources like vision screenings coupled with free eyeglasses provided by Warby Parker; mental health screenings and services offered by a combination of public and private clinicians; afterschool and summer enrichment programs that provided child care for working families and extra learning opportunities for students; and a cadre of specially trained social work interns, sponsored by New York City’s six schools of social work, who assist public school students living in temporary housing.

A lesser-known part of the New York City community school story is the role of the Coalition for Educational Justice, a parent advocacy organization that identified community schools as a preferred reform strategy after surveying and consulting with families across the city. As CEJ’s Natasha Capers has written, CEJ implemented a campaign in early 2013 to make improving public education a key issue in that upcoming mayoral race; this campaign included extensive family outreach and consultation over several months. Capers noted that, with the help of a design team of policy experts, CEJ then issued a roadmap for the next mayor that highlighted all the top ideas, including community schools. Parent demand as an instigator for this reform makes its continuation and expansion even more urgent because COVID-19 has demonstrated that the supports and services offered by community schools are needed by New York City’s families now more than ever.

Taken together, these factors—family demand, documented success, new post-COVID realities—make expansion of the community school strategy a no-brainer. Recent action by Mayor de Blasio and the City Council will ensure continuation and growth of community schools through 2022, but advocates are rightly concerned about the future that lies beyond the current administration. The city can use its experience over the past eight years in leveraging and making better use of existing resources while also tapping into new federal dollars, including those allocated for high-need schools in the American Rescue Plan Act.

In addition, the Biden administration has proposed expanding the Federal Full-Service Community Schools Program in the U. S. Department of Education from its current annual budget of $30 million to $442 million in 2022. New York City should be first in line to capitalize on this national momentum. But, to do so, we need a Mayor who believes in the idea of every school a community school.

***

Jane Quinn is currently a doctoral student in Urban Education at the City University of New York. From 2000 through 2018, she served as Director of the Children’s Aid National Center for Community Schools.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Cannot Fine Its Way Through a Covid Recovery

"Save Small Business" (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

The next few years in New York City will no doubt be challenging.

In a few months, a new mayoral administration and the next City Council will inherit the worst financial situation in 20 years. The path ahead will be difficult as we try to lure tourism and business back to New York, in hopes of closing budget gaps that will threaten vital social services above all else. We must learn from the lessons of the past, however, to guarantee this isn’t a recovery built off the backs of those already struggling to get by.

When New York City faced a similar budget crunch 20 years ago after 9/11 caused a mini-depression, Mayor Bloomberg turned to fines, especially around parking violations, to help meet the shortfall. These measures were as controversial then as they are now, feeding into a national trend in which monetary penalties to deter illegal behavior became a revenue stream. Research has shown, however, that fines and fees, no matter the type, disproportionately impact communities of color and immigrant populations. The thrust of our city’s recovery should not stem from regressive policies that push everyday New Yorkers deeper into crisis rather than out of it.

This also applies to small businesses, the heartbeat of our communities. The city must not look to them as an easy target to build back up its coffers. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, the city has continued to target small business owners with hefty fines for minor infractions. While finding new streams of revenue will be an important factor in dealing with the budget shortfall, onerous fines and overzealous enforcement of minor violations cannot continue to be the solution. Economic data presented last month shows that 78% of New York State businesses with fewer than 500 employees are still struggling from the impacts of covid, according to a March report from State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli.

Those numbers become even more real when you walk down Austin Street, Queens Boulevard, or 108th Street in Queens and ask business owners, many of whom are immigrants trying to live the American dream, what the last year has been like.

There are simple steps we can take to lift all boats. We must take a completely new approach that prioritizes supportive case-workers over penalty-issuing inspectors. That’s not to say a business owner who price-gouges face-masks or a restaurant owner who keeps a dirty kitchen shouldn’t be punished. But those who try to adapt to the constant change in rules shouldn’t be a revenue line in the city’s budget.

Next, the Department of Small Business Services must ramp up its outer borough outreach. The only time many here in Queens interact with the agency — or the city as a whole — is when an inspector makes an unannounced visit. The laudable efforts by SBS during covid shouldn’t go away once we declare victory on this virus. The next mayoral administration and City Council must work together to create a post-covid small business task force that allows New Yorkers to responsibly follow their dreams and provide for their families.

Third, we need to completely stop relying on fines as a first-strike warning for small businesses in their first year. Instead of fining an entrepreneur into collapse, we need to work with them to rectify the issue in a constructive way as opposed to meeting a violation quota.

These steps mark only the beginning of what needs to be a fundamental restructuring of the relationship between our small businesses and those tasked with enforcing our city’s rules and regulations. There’s a lot of work that will need to be done, but I know it’s possible to ensure that we can build Queens and New York City back stronger than ever before, with a budget that is balanced and an environment where small businesses can thrive. As we continue to recover from the pandemic, we must take advantage of the opportunity to create a fairer city that looks out for all its residents. In the City Council, I’ll make sure that becomes a reality.

***

David Aronov is a Democratic candidate for the New York City Council in Queens’ 29th District. On Twitter @DavidforQueens.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Homeownership Supply is the Affordable Housing Blind Spot in New York City

Housing (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office)

Charged with leading post-covid New York to a more equitable future, our next mayor should increase opportunities for New Yorkers to build equity through affordable homeownership.

Historically a blind spot in our city’s, state’s, and country’s affordable housing discussions and budgets, which tend to focus on rentals, affordable homeownership is a way for low-income people to begin to build wealth and for us as a city to reduce racial and economic inequality. Homeowners are wealthier than renters at every income level, and for the majority of homeowners most of their wealth comes from their homes.

Homeownership is elusive for most New Yorkers. In 2018, the last year of available data, just 33% of residents owned their home, dipping as low as 18% in the Bronx. White New Yorkers, at 43%, are far more likely to own their home than Black (27%) or Hispanic New Yorkers (17 %), and it’s getting worse: a recent report from the Black Homeownership Project showed that the Black homeownership rate has dropped by 13% over the last two decades citywide, preventing long-term equity building and exacerbating racial wealth gaps.

Yet, expanding new opportunities for working families, especially of color, to purchase affordable homes is often left out of New York’s housing policy discussions entirely. When it is brought up, even within the affordable housing sector, the conversation is often focused on demand-side challenges like down-payment assistance, credit-building, first-time homebuyer education, and ending discriminatory practices in the homebuyer market. These issues are important, but they miss the larger crisis: there are not enough homes available at prices accessible to working-class households to move the needle.

A Center for NYC Neighborhoods analysis of ACRIS data showed that in 2019, there were approximately 9,000 homes purchased for $420,000 or less, which is considered accessible with the right financing to low- and moderate-income homebuyers. In a city of 8.3 million people and over 1 million owner-occupied homes, this number is shockingly small and makes up only 22% of all home purchases of 1-4 family homes, condos, and co-ops.

To make matters worse, homebuyers, even with the right credit, down-payment assistance, and mortgage qualifications, were beat out by cash buyers over half the time. According to a recent study from Center for NYC Neighborhoods, 52% of all low-priced homes were bought with cash, often by private equity groups, limited liability corporations, or investors rather than individuals seeking to move in.

The good news is that the conversation is changing in a significant way, and our next mayor has a blueprint from 90-group strong The United for Housing coalition with specific recommendations to expand affordable rental and homeownership housing.

It calls on the next mayor to expand and reform the city’s Open Door homeownership construction program, invest in preservation strategies that would convert rental properties into resident-owned limited equity cooperatives, and utilize Community Land Trusts as a method to keep people in their homes while creating permanent affordable homeownership opportunities for low- to moderate-income New Yorkers.

Better yet, the plan creatively challenges institutional processes like New York’s tax lien sale and down-payment assistance programs, putting forward solutions that would utilize limited financial resources to bolster household and community assets for residents and neighborhoods. In other words, the report helps arm our future leaders with the detailed policies they need to tackle this crisis – and candidates are listening.

Some of the candidates for our city leadership have addressed these disparities and put forward specific homeownership policies that expand the conversation past the demand-side solutions that place the onus on the homebuyer to break into the homeownership market. Still, the issue hasn’t been thoroughly addressed in the larger housing debate. New Yorkers deserve to hear more from candidates about how they will not just help them rent an affordable apartment but buy one and build wealth and own a piece of their neighborhood.

Affordable homeownership supply cannot be an afterthought in a sea of rental development strategies. Even in New York, the idea of homeownership cannot be a pipe dream reserved only for the rich or famous. Increasing affordable homeownership opportunities must be a central pillar of the next mayor’s vision to build the smart, progressive, and equitable city New Yorkers deserve.

***

Matt Dunbar is the VP of External Affairs at Habitat for Humanity New York City, collaborator with Interboro Community Land Trust, and an Advisory Board Member of the New York Housing Conference. On Twitter @misterdunbar & @HabitatNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.